POPULAR knowledge of the fascinating science of archaeology and of the priceless treasures unearthed has been greatly increased by the recent best-seller, Gods, Graves and Scholars by C. W. Ceram. Dartmouth men who have an interest in this subject are perhaps unaware that the College has, in its Assyrian bas-reliefs, one of the finest and most valuable of these art treasures from the past. Over 2,800 years old, these sculptures originally came from the palace of the Assyrian monarch, Ashurnazirpal II, who reigned in the 9th century B.C. Only the British Museum has ancient Assyrian bas-reliefs which can match the excellent detail of those at Dartmouth.

Sir Henry Creswiche Rawlinson, the eminent English archaeologist, who figures prominently in Ceram's book, presented the sculptures to Dartmouth nearly a hundred years ago. Alumni effort was an important factor in the gift, and how the art treasure was acquired—and then transported to this country—makes a story that is not without human interest.

In the year 1852 Prof. Oliver Payson Hubbard, then librarian of the College and onetime professor in the Medical School, wrote to Dr. Austin Hazen Wright, class of 1830, who had been since 1840 a missionary of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions at Oroomiah, Persia. Professor Hubbard, a longtime friend of Dr. Wright's ever since they had attended medical school together, asked Dr. Wright if he might not be able to acquire several "mementoes of the ancient cities that are now being opened on the Tigris." Wright, upon receiving the letter, was only too happy to try to acquire several sculptures for his Alma Mater.

The excavations in this area of northern Mesopotamia at the time were under the direction of Sir Henry Rawlinson, then English Resident in Bagdad, and the removal of sculpture had to be sanctioned by him. Although Wright did not know Rawlinson personally, he made contact with the English consul at Tabriz, a Mr. Stevens, who forwarded the request to Rawlinson. Rawlinson granted that Dartmouth should receive six out of eighteen slabs that had been collected. The cost of the shipment was to be all that Dartmouth would have to pay, and $300 for this purpose was appropriated by the College. A Mr. Marsh and Dr. Lobdell, who were missionaries in the vicinity of Calah, the ancient city of Ashurnazirpal, offered to help prepare the sculptures for Dartmouth.

The reliefs from Calah were originally a foot thick and about eight feet high. In order to ship the slabs each sculpture had to be sawed in three pieces and the thickness reduced to about three and one half inches. When this was completed, the men doing the work managed to transport the sculptures by donkey from Calah to Mosul, a town some twenty miles away. However, when they reached Mosul, it was found that the slabs still weighed too much for the camels that were to transport them to the port of Alexandria on the Mediterranean. The reliefs had been packed by covering them with wool and "ketchek," a type of felt about one half inch thick. All this had to be undone, and the sculptures were cut into smaller sections.;

The men working on the packing were grieved in March 1855 when Dr. Lobdell, who had done so much of the work, died from typhus. The work had to be finished at Mosul by a Rev. W. F. Williams, and the sculptures were finally ready in the summer of 1855 to be sent to Alexandria. They left Mosul on July 25 by camel caravan for the Mediterranean approximately five hundred miles away. Twenty-eight boxes were sent, and the cost up to this point already exceeded the expected price for the whole trip, as $310 had been spent.

The plan was to ship the sculptures by steamboat from Alexandria to Beirut where they could be placed on the yearly wool-boat for Boston. However, the agent at Alexandria did not follow his orders and sent the slabs by sailing vessel to Beirut, which of course proved to be much slower. Consequently after all this preparation the sculptures arrived three days too late at Beirut for the Boston boat. This meant that the sculptures would have to remain in the city for about a year. Mr. Williams wrote at this time, quite appropriately, that time meant nothing to the people of the Near East.

The slabs were stored in the Beirut customs house and were still there in the summer of 1856. Finally, on December II, 1856 they arrived in the United States and were found to be in much better condition than many other collections in this country. They were first set up in 1857 in Reed Hall and were later moved to Butterfield Hall. Years later they were again moved, part to Carpenter Galleries and part to the College Museum. All told, bringing the sculptures of Ashurnazirpal II to Dartmouth cost $600—a sum which may have seemed large then but which in the light of their present worth is minute. As a gesture of gratitude to Sir Henry Rawlinson the Trustees of Dartmouth at the Commencement of 1857 conferred on him the honorary degree of LL.D.

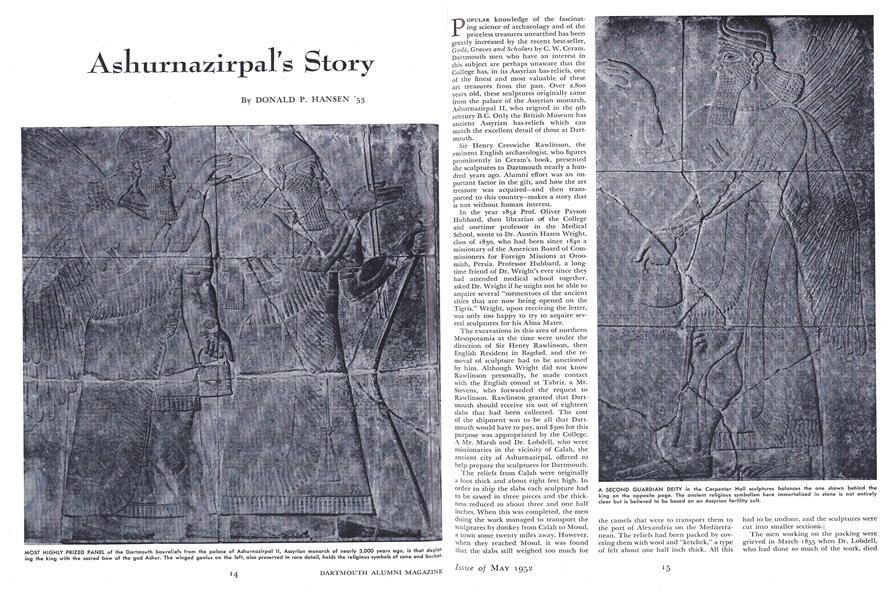

THE palace of Ashurnazirpal from which the sculptures were taken was situated 011 the east bank of the Tigris River about 200 miles north of the famous city of Bagdad. The palace and its associated temples were built upon a huge stone-faced, mudbrick platform. Although the main part of the palace was mud-brick, the interior was finished in cypress, cedar, and various other types of oriental wood. Large wooden doors protected the entrances, and as apotropaic forces to ward off evil, gigantic, sculptured, human-headed lions were placed at the doors. There were approximately 25 rooms in the palace, and lining the walls of each were sculptured slabs forming a wainscoting eight feet high. Above this frieze the walls were stuccoed and painted with red, black, yellow, and white designs.

These sculptured slabs, of which Dartmouth's are a sample, were carved in a gypseous alabaster that was native to the Assyrian plain. It was quarried along the ridges bordering the river and was white when first cut. However, upon exposure to the air it gradually deepened in tone until it reached the tan color that the reliefs have today. The purpose of the slabs was protective; they helped to guard the walls from the destructive floods and dampness known to the region. The idea of sculpturing them for religious purposes and spreading the glory of the king developed from this utilitarian purpose.

There were two types of sculptures that decorated the walls of the palace at Calah. One type was devoted to the martial exploits of the Assyrian nation under Ashurnazirpal; the other, of which the Dartmouth reliefs are an example, showed certain religious rituals. The specific meaning of the ritualistic acts has been lost to us through the ages; however, certain fundamental facts have been deduced by many scholars from a long study of Mesopotamian iconography.

The religious acts, as portrayed on the reliefs, are based on a fertility cult—derived by the Assyrians from the peoples of the lower portion of the Mesopotamian valley. Winged genii (in this sense genius means guardian deity) play a most important part in the ritual and are associated with a sacred tree, which is a stylization of the date palm, the staple food of the lower portion of the Mesopotamian valley, generally called Babylonia. However, in Assyria, the tree was not only a symbol of fertility, but was also believed to have other powers beneficial to man. The most generally accepted theory concerning these winged genii and their relation to the sacred tree is that the act symbolically represents the fertilization of the date palm. The gen11 usually hold two objects in their hands. One hand clutches a conical object which may be a stylized interpretation of the male inflorescence of the date palm; the other hand holds a pail or bucket, which probably held some kind of magical fluid.

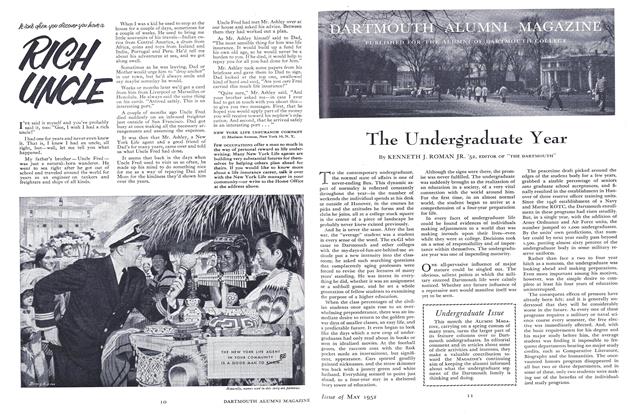

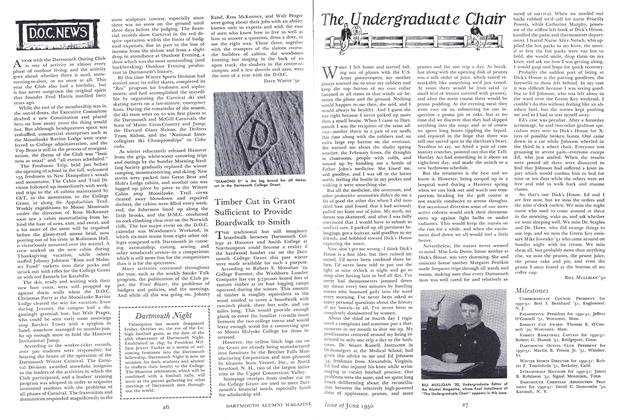

The three bas-reliefs on display at the Carpenter Galleries represent two winged genii flanking a relief of the great king himself, Ashurnazirpal II. The figure on the left shows a genius in an act of worship. In the illustration he is holding the "cone" and bucket in the traditional position. The divine rank of the figure is shown by the wings, the ritual objects, and the twohorned cap upon his head. Each of these sculptures manifests the strong paternization of Assyrian art with a great interest in detail. Notice the beard and hair of the figure with the alternating surfaces of curved and straight lines. The identical patterns in the clothing, hair and musculature are repeated on each relief and show quite clearly Assyrian conventionalism. The musculature being so highly accentuated and stylized vividly expresses the force and temperament of the warlike king and Empire as a whole. In spite of the conventions one cannot neglect this tremendous energy and vitality. The figure is clothed in a short tunic over which a long mantle falls. Sash, daggers, tassels, fly-whisk, necklace, armbands, and heavy earrings finish the decorations of the figure. The genius on the right side of the slab of the king is essentially the same as this one.

The most valued sculpture owned by the College in this series of Assyrian reliefs is the slab of the king. It is prized not only because Dartmouth is most fortunate in having one of the few sculptures of Ashurnazirpal, but because the quality of the sculpture can be equalled or surpassed only by similar sculptures in the British Museum. Upon his head the king wears the royal cap, to which is attached a tasseled streamer. In his left hand he holds the sacred bow of the great god Ashur and in his right clasps two arrows with the heads pointing upward. Two arrows held in this manner symbolize peace or devotion.

Dartmouth's relief is particularly valuable in that the incised designs representing the embroidery on the robes of the monarch are in such an excellent state of preservation. Embroidery from Mesopotamia was known throughout the ancient world, and we can conceive of its magnificence and intricacy from these incised designs. The subject-matter of this embroidery is religious, but much of the detailed significance is obscure. Most important to notice, however, is the grace and handling of the engraving. The most heavily embroidered section of the royal dress is the sleeve, where parallel bands of genii, griffons, winged-horses and the like surround a central section depicting the winged-disk of the supreme god of the Assyrian pantheon, the war-god Ashur.

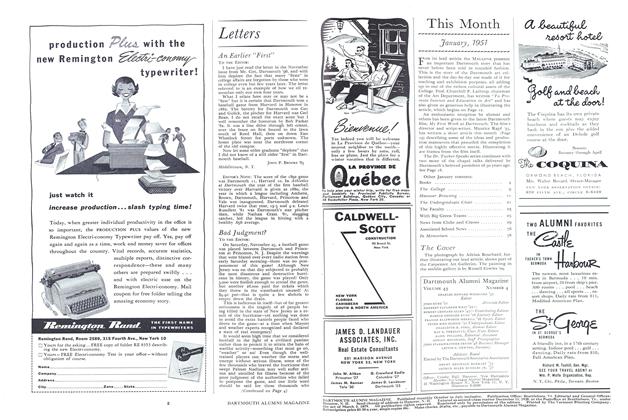

In the College Museum there are three other bas-reliefs on display representing two genii, the sacred tree, and an eunuch kttendant of the king. The genius on the left differs slightly from most in that he is not shown with wings and in place of the horned cap wears a fillet around his head with a rosette in the center. However, he holds the sacred pail and is depicted in a religious ritual. Across each of the figures runs an inscription of cuneiform writing which has come to be called the "Standard Inscription," repeated on relief after relief without alteration. It tells of the wars and battles of Ashurnazirpal and his building of the palace. It is obvious that little regard has been paid the sculptures, since the writing passes directly over the figures. No one in the palace could escape the omnipresent king and his wars. Since the glorification of the king was the primary motive behind the decorating of the slabs, the monotony and bombast of the script are, in part, quite understandable.

The relief in the center of the display in the Museum shows a typical genius beside the sacred tree performing a mystical ritual, while the last figure on the right is a fine example of the eunuch attendant of the king. These eunuch attendants held a particularly high place in the royal court and are" frequently depicted beside the monarch. The beard is absent, though the hair is represented in the traditional manner. This eunuch holds the king's bow, quiver and arrows, and a mace, the latter being a symbol of authority. At his waist a sword is thrust in the sash with the scabbard extending behind. Near the end of the scabbard are attached two beautifully entwined lions. The lions expressing mightt and power to the Assyrian people was. often used as a decoration for this fearful weapon.

Perhaps when Dartmouth College first: received these splendid slabs, it little realized how fortunate it was; for today their value is immense. Perhaps also, Professor Hubbard had no idea of what their present value would ever be when he hopefully wrote to Dr. Wright, "Please let one of the slabs be a king if possible!" Today this work of art ranks among the most perfect specimens of its kind of an age long pastimmortalized in stone.

MOST HIGHLY PRIZED PANEL of the Dartmouth bas-reliefs from the palace of Ashurnazirpal II, Assyrian monarch of nearly 3,000 years ago, is that depicting the king with the sacred bow of the god Ashur. The winged genius on the left, also preserved in rare detail, holds the religious symbols of cone and bucket.

A SECOND GUARDIAN DEITY in the Carpenter Hall sculptures balances the one shown behind the king on the opposite page. The ancient religious symbolism here immortalized in stone is not entirely clear but is believed to be based on an Assyrian fertility cult.

A BEARDLESS EUNUCH, part of three additional panels in the Dartmouth Museum, is shown holding the king's bow and arrows and a mace, symbol of royal authority. On all the slabs, cuneiform writing tells the story of the martial exploits of Ashurnazirpal and how he built his palace on the Tigris.

STUDENT AUTHOR: Donald P. Hansen '53 of Hastings-on-Hudson, N. Y., poses before the bas-reliefs described in his article. As a Senior Fellow next year he will study the ancient civilizations of Mesopotamia.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1952 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

May 1952 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

May 1952 By KARL W. KOENIGER, DONALD BROOKS, HOWARD A. STOCKWELL -

Article

Article25 Years After

May 1952 By JAMES D. BINDER '52 AND THOMAS L. PAPST '52 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Year

May 1952 By KENNETH J. ROMAN JR. '52 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1950

May 1952 By ENS. SCOTT C. OLIN, USN, SIMON J. MORAND III, GLENN L. FITKIN JR.

Article

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Fund

May 1945 -

Article

ArticleTimber Gut in Grant Sufficient to Provide Boardwalk to Smith

June 1950 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

January 1951 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

May 1962 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleSpring Schedules

March 1960 By RAY BUCK '52 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

December 1948 By William P. Kimball '29