byEdward C. Kirkland '16. University of Wisconsin Press, 1952; 59 pp.; $1.50.

Edward C. Kirkland, professor of history in Bowdoin College, delivered the Knapp History Lectures as visiting professor at the University of Wisconsin during the second semester of the 1950-51 academic year. Business inthe Gilded Age is the product of this assignm ent and a preview of a forthcoming revaluation by Professor Kirkland of the period between the Civil War and the beginning of the twentieth century. The Knapp Lectures are thumbnail sketches of the views of three diverse commentators of this period: Charles Francis Adams Jr., the descendant of Presidents and the brother of the famous Henry Adams; Edwin Lawrence Godkin, journalist and moralist; and Andrew Carnegie, both actor and critic during America's gilded age of business.

Although Charles Adams led a varied lifehe was a gifted amateur historian, an overseer of Harvard, and the president of the Union Pacific Railroad—Professor Kirkland has chosen to identify Adams as a (government) bureaucrat because of his work with the Massachusetts Railroad Commission during its formative years. As either a government or business bureaucrat, however, Adams' appraisal of business behavior was essentially pragmatic, and he was generally unfavorably impressed with what he saw. For example, "Honor for its own sake and good faith apart from self-interest are, in a business point of view, symptoms of youth and defective education." But Adams was no reformer; his views on the public were only slightly less sardonic, and Professor Kirkland finds that Adams was led in disillusionment to adopt a grim and amoral survival-of-the-fittest approach to social affairs.

Edwin Godkin, founder of The Nation and one of the most influential journalists of his era, was both more sanguine concerning contemporary business practices and somewhat more hopeful of their improvement than Adams. Godkin viewed the keen individualism and materialism of early industrial America as the inevitable result of its youthfulness, but he had little good to say of businessmen, frequently considering them cultural illiterates whose hands could often be found in the public's pockets. At the same time he found in the "principle of competition" the basic natural law "by which Providence secures the progress of the human race." During the later period of his life, however, Godkin became embittered by such events as the silver movement, the Spanish-American War, and the idle and wanton rich. Democracy, he concluded, was a failure, and virtually all moral standards were debased.

Andrew Carnegie was both an industrialist and a frequent commentator on public and business affairs. It is in the latter capacity that Carnegie is of interest to Professor Kirkland, and it is of course Carnegie who finds in business the appropriate challenge to intelligent and idealistic youth. But in the end Carnegie joined Adams and Godkin at least partially finding the quest for money both ignoble and sordid, and accepted what he believed to be the millionaire's obligation of dispensing his money for the good of the people.

Professor Kirkland's preview achieves the distinction of being both entertaining and informative, and one looks forward to the completion of his study.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1952 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Article

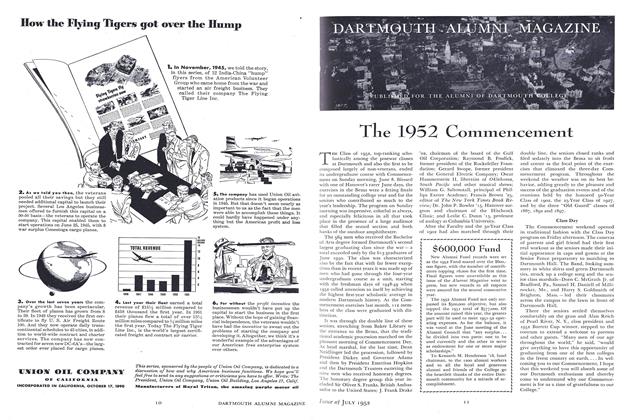

ArticleThe 1952 Commencement

July 1952 -

Article

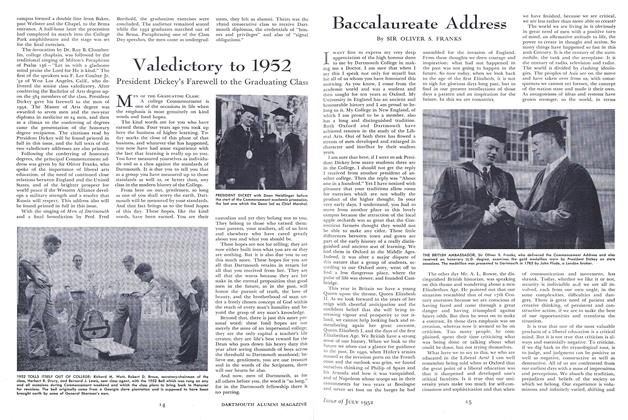

ArticleBaccalaureate Address

July 1952 By SIR OLIVER S. FRANKS -

Article

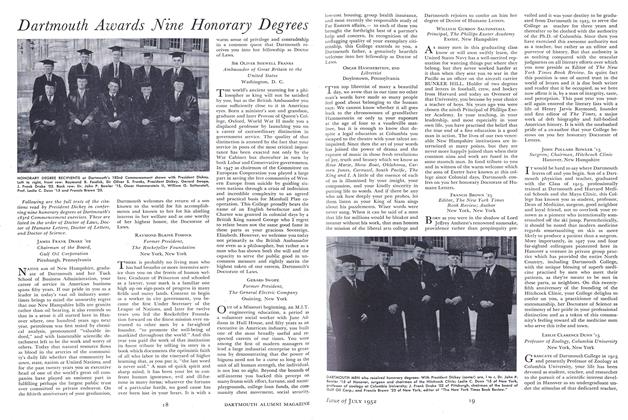

ArticleDartmouth Awards Mine Honorary Degrees

July 1952 -

Class Notes

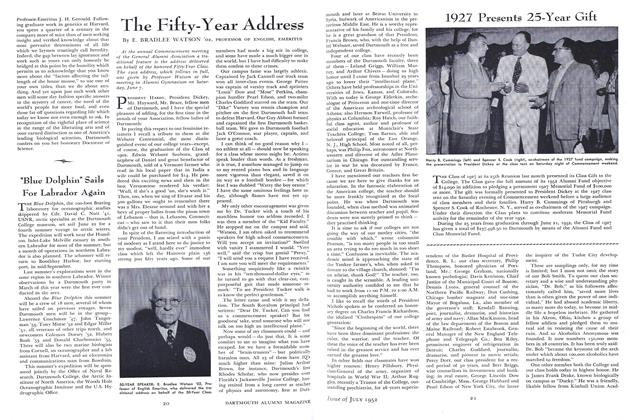

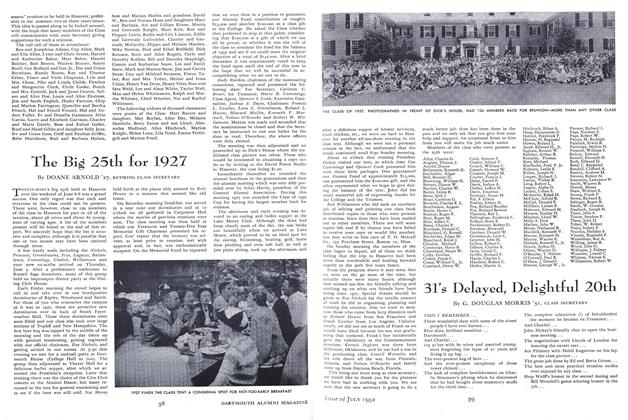

Class NotesThe Big 25th for 1927

July 1952 By DOANE ARNOLD '27 -

Class Notes

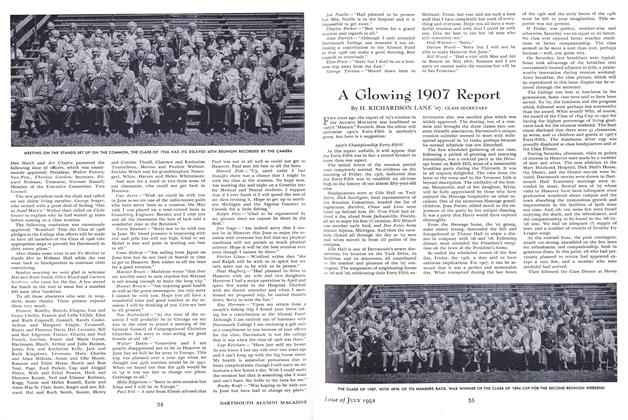

Class NotesA Glowing 190 7 Report

July 1952 By H. RICHARDSON LANE '07

L. G. Hines

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

MAY 1969 -

Books

BooksTHE PAPERS OF ADLAI E. STEVENSON: BEGINNINGS OF EDUCATION 1900-1941.

OCTOBER 1972 By CHARLES M. WILTSEL -

Books

BooksCONGRESS IN CRISIS: POLITICS AND CONGRESSIONAL REFORM.

APRIL 1967 By DAVID K. MARTIN '54 -

Books

BooksROBERT FROST, ORIGINAL "ORDINARY MAN"

APRIL 1929 By Evan A. Woodward -

Books

BooksMONEY AND CREDIT

May 1935 By G. W. Woodworth -

Books

BooksA HISTORY OP AMERICAN GOVERNMENT AND CULTURE

June 1931 By H. B. P.