ByStanwood Cobb '03. New York: VantagePress, 1954. 47 pp. $2.00.

Charles Francis ("Clothespins") Richardson wryly dubbed himself "grandfather of yellow journalism" when a student of his who later became editor of a New York Sunday supplement, doubled its circulation in a single week by printing a full-page picture of a circus baboon in lurid yellow. For this editorial miracle Hearst drafted the worker of it to help found his "empire."

"The Magnificent Partnership," though far more genteelly, tells a similar story of an editorial battle of the 1850's from which emerged victoriously America's first "colossal" popular weekly, the New York Ledger. The literary Partner in victory was Sylvanus Cobb Jr., uncle of author Stanwood, himself a prolific writer and director of the Chevy Chase School. Sylvanus it was who provided a highly meritorious baboon" in the form of a prodigious opus of the most widely read thrillers of his three decades — 158 novelettes and 1,062 shorter tales. The publishing Partner, George Bonner, anticipating our Hearsts, Curtises, and Boks, stole Sylvanus from Boston's Flagof Our Union and with his best-known thriller The Gunmaker of Moscow, boomed by an "orgy of publicity," started his Ledger on its flight till its circulation reached the then unprecedented half million mark among the "newly educated masses." Partner Cobb grew rich and Partner Bonner amassed $6,000,000.

Of the uncle's fabulous, yet now forgotten literary remains, nephew Cobb writes with modest restraint: they lacked "the quality of literary greatness"; "vivid scenes and plots never failed to sustain interest"; their variety of times, people, and places "called for a power and vigor of imagination such as few writers have possessed." Captious critics crumbled that "ninety-nine out of every hundred" readers preferred Cobb to George Eliot; but champion Bonner retorted: "I believe in good old thrilling stories - with one of your inimitable heroes. They take, and no mistake!"

""Thousands - yes, millions loved his work," we can safely believe. And few of them would have failed to echo reverently the assurance of one who voiced the century's sine qua non of praise: "In all his work there has never been an impure word "

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

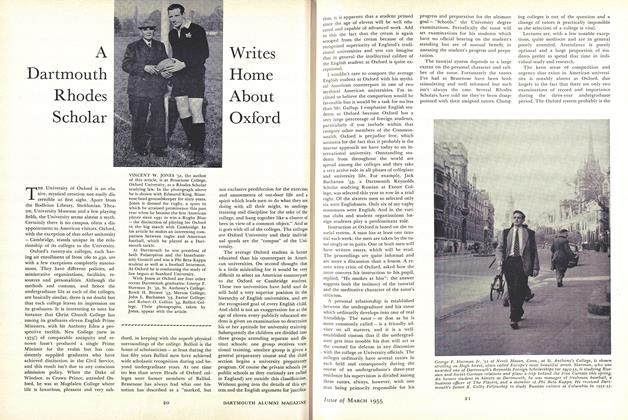

FeatureA Dartmouth Rhodes Scholar Writes Home About Oxford

March 1955 -

Feature

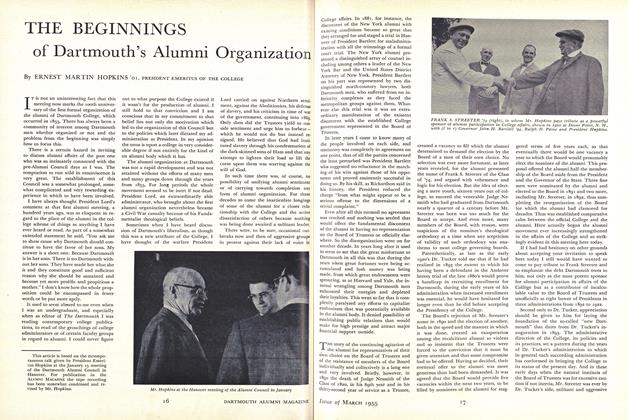

FeatureTHE BEGINNINGS of Dartmouth's Alumni Organization

March 1955 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS 01 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1955 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1955 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES JR., TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE

E. BRADLEE WATSON '02

-

Books

BooksFLETCHER, BEAUMONT & Cos.,

May 1947 By E. Bradlee Watson '02 -

Article

ArticleThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1952 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Books

BooksSAGE OF THE SACRED MOUNTAIN.

March 1954 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Class Notes

Class NotesThe 55th Reunion of 1902

July 1957 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02 -

Books

BooksTHE JADE NECKLACE OF LIN SAN KWEI.

MARCH 1959 By E. BRADLEE WATSON '02

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Articles

December 1956 -

Books

BooksSOVIET CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE: THE RSFSR CODES.

MAY 1966 By CHARLES B. MCLANE '41 -

Books

BooksROBERT FROST POETRY AND PROSE.

DECEMBER 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksAN INTRODUCTION TO PUBLIC OPINION

July 1940 By Michael Choukas '27 -

Books

BooksSHOTS HEARD ROUND THE WORLD.

January 1958 By RICHARD W. MORIN '24 -

Books

BooksCHINESE INFLUENCE ON EUROPEAN GARDEN STRUCTURES

April 1937 By Walter Curt berhrendt