The North, in which Dartmouth has long had an active interest, emerges as an area of vast economic and military importance

A NORTHERN college with northern traditions, Dartmouth cannot help being interested.

The most powerful adversaries in the history of the world, the Soviet Union and the United States face each other across the Mediterranean Sea of the future, the Arctic Sea.

H bomb or A bomb cannot alter the fact that if World War 111 comes its strategic center will be the North Pole. So said General Arnold, Chief of Military Aviation in World War 11. So says Vilhjalmur Stefansson.

Most informed aviation experts realize that it is easier for modern planes to fly from Canada or the United States by the North Pole route to the Soviet Union or vice versa, than it was for the Romans to sail to Carthage across the Mediterranean. Nearly everyone now knows that arctic flying conditions average good, better than, say, from New England to England.

On January 3 Lieut. Gen. Joseph Smith, Commander of the Military Air Transport Service, reported that one of its Alaskabased squadrons has flown more than 700 missions over the North Pole in the past three years. In 195 a the 58th Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron flew regular B-29 weather missions into the polar zone almost daily.

The Navy is also interested. The Mediterranean Sea of the future which contains the shortest route by air between the Soviet Union and North America is also traversable by water. True, the floating ice prevents passage by sailing ships and by the most powerful steamers, but specialists know that the ice in the Arcticsea is shallow enough, and the water underneath it deep enough, to permit wholesale passage by submarines. It is a sobering if dramatic thought that under polar ice may travel, infinitely compressed, the hot flames of A bombs.

But it may not be war but peace. What then? Still the most powerful adversaries in the history of the world, the Soviet Union and the United States are committed to a rivalry of many kinds, one of which will be comparative success in developing the Arctic.

With outdoor traditions of snow and cold, Indian culture and cunning, camping and exploration, Dartmouth men are studying the implications of this new frontier. A new frontier it certainly is. They need scarcely to be told by the Department of Geography that it is a front of 3,000-odd miles extending from southwestern Alaska across Canada to Labrador and Greenland. The front across Norway, Sweden, Finland, European Russia, and Siberia is even longer.

The wearers of the green need lament no longer the passing of "The Last Frontier," the one described in traditional American history books. It was first the Rocky Mountains and finally California where ambitious pioneers found themselves ankle deep in the surf of the Pacific Ocean. The cramping conception of a closed world has been suddenly replaced with the revolutionary expansion of almost limitless territory. Dartmouth students need not climb Mt. Washington to catch a romantic glimpse of that enormous uncolonized territory spreading northward beyond the colonized fringe of southern Canada. It is bigger than all of the 48 states lumped together. The Old World counterpart is still bigger.

It is indeed a breath-taking panorama, a challenge to young men, especially to undergraduates at Dartmouth who dislike suburban houses crowding in and spoiling their vistas of a free life and who dislike even more city apartments with no vistas at all except stony ranges of skyscrapers that cannot be adventurously scaled.

These undergraduates need not think just of military developments in Alaska and Canada, Iceland and Greenland, though if one wishes a military future, one has an opportunity in Alaska and Canada with North American armed forces spending scores of millions of American and Canadian dollars on air fields and the exploitation of oil. Every decade the population is increasing 20 or 30 percent.

The majority, of course, will think, as men in their right minds always do, in terms of peace and prosperity. The Far North has a need of trained engineers and technicians fantastically great. It is as fantastically great as the potential development of oil and minerals, coal and water power, housing and food. The potentialities of food, meat for example, are so great that the standard of living could be perceptibly increased for the whole world in the course of time.

So says Stefansson, one of the greatest explorers of the Arctic, and it is his con sidered opinion.

DARTMOUTH alumni, like the alumni of any college, though they know that the earth is a sphere, tend to think of it and talk of it as a cylinder with the traffic flowing from east to west or west to east. Even so astute a mind with naval orientation as that of Franklin D. Roosevelt, often described as a globe-minded president, talked of a spherical earth but obviously thought of a cylindrical earth.

The immediate results of such thinking translated into policy are disheartening, in fact fraught with catastrophe. Americans have developed what might be called the defense by desert policy. Most of us are heading towards a warm south. The Soviets have developed what might be called the exploitation by colonization policy. Our newspapers treat the Far North as a place of horror and frustration from which reckless and intrepid pioneers are saved by equally reckless and intrepid aviators and flown to hospitals to thaw out. Soviet newspapers treat the Far North as a place of contentment and fulfilment into which hardy pioneers and engineers move and become fat and rich.

What are the implications? Let Stefansson speak. Dartmouth alumni have had the stimulation of hearing the great explorer expound his thesis, which runs somewhat as follows.

I lie Soviets seem to be winning the cold war in the Arctic in more senses than one. The United States and Canada seem to be losing it, for they are regarding the Arctic as an uncolonizable wilderness and spending money on only a few military outposts. The Soviets are not neglecting military establishments, but they are filling everything in between.

Consider the facts of population and migration.

Our continent can boast of no city as large as 50,000 north of Edmonton. The Soviet Union has at least go cities larger than 50,000 each.

The large city farthest north on our Continent is Edmonton, in central Alberta. It is the most important rail and air center of the Canadian Northwest, a distribution point of rich farm country and coal-mining regions, the hub of thriving fur trades, the center of varied manufactures, the seat of the University of Alberta some 46 years old and of a Jesuit college affiliated with Laval University some 100 years old. But Edmonton has apopulation of less than 200,000.

One hundred fifty miles farther north than Edmonton, lies Moscow, the largest city in the Soviet Union. And Moscow hasa population of more than 5,000,000.

The population north of Edmonton Canadians, Alaskans, and Greenlanders numbers fewer than 1,000,000, but more than 100,000,000 people are living in the corresponding area of the Soviet Union.

Relatively Canada ignores her great river, the Mackenzie, which connects her southerly railway belt with the waters of her arctic coast. The steamers shuttling back and forth in summer are few and small; in winter tractors are few and carry little freight.

The Soviet Union, on the other hand, utilizes just as fully as possible her three great rivers, the Ob, the Yenisei, and the Lena, which connect her railway belt of the south with her northern coastal waters. Ships heavily laden with flour and manufactured goods slide down the channels of these rivers and slide back up with fish and raw materials. When these rivers freeze, traffic goes right on, for they become ice highways for trains of tractors and trucks.

The North Americans and the Soviets have entirely different news slants on the Polar North. In our free press, the tendencies of American newspapers are to portray in glowing colors the southward and westward trek to California, New Mexico, and Arizona. Canadian newspapers play up the trek to southern British Columbia and play down with sombre hues the darkness and hibernation and stagnation of arctic wildernesses. Headlines loom big when explorers crash onto polar ice from the air or into crevasses from snow fields. When explorers and colonizers live month after month and year after year comfortably and without mishap, they go unnoticed by the press.

The Soviets slant their news in the opposite direction. They have established an official program of northward colonization. They want accordingly stories about orderly advances and accomplishment in building cities, digging mines, cutting down forests, excavating minerals, catching fish, raising reindeer, and collecting furs. So they play down bad news and play up good. Statistics are headlines in Moscow. Frozen feet and amputations, heroic rescues under Hollywood conditions, incredible bravery on frozen tundras and in frozen seas these are headlines in America.

Who then is winning the cold war? Washington says that we are. We are keeping the Arctic empty except for such activities as those of our Navy in northern Alaska and the Air Force in northern Greenland. Moscow says that the Soviets are winning. Their populations are advancing into the Arctic.

Informed American experts are studying Soviet statements to see how much truth and how much falsehood lie in their claims. Their claims, if true, should cause the United States and Canada the greatest concern. Sometimes openly, sometimes tacitly, Soviets say that they are building railways into their North. One of them, 1,100 miles long and completed during World War 11, nearly or quite connects with the northern sea and runs through Ukhta and Vorkuta, cities of 40,000 and 30,000 persons. The Soviets claim that they have great fleets of steamers on all three Mississippi-size rivers connecting their southern railway belt with the Arctic Sea. They have, they insist, corresponding trains of sledges drawn by track-laying tractors along these ice highways in winter. They boast about steady growth in their northern cities in many of which winters are colder and longer than in any section of the Alaskan and Canadian Arctic. These cities, according to Soviet claims, may compare favorably with those in the north temperate zones of Europe and America and have plenty of heating in houses and factories, machine shops and hospitals, theatres and schools. Their inhabitants are represented as productive and prosperous.

If it is to be war, we should remember that with the strategic center at the North Pole, not only is Moscow (over 5,000,000) nearer to the North Pole than Edmonton (under 200,000) but also Leningrad (over 3,000,000) is nearer than Anchorage, founded in 1914 as a construction camp for railroad workers and now under 40,000.

If it is to be peace, how do we come out on total population? Stefansson says, "If we take the distance from Arnold's strategic center to the northern suburbs of Edmonton and scratch upon the globe a pole-centered circle of that radius, we find within it fewer than 200,000 people of Alaska, Canada, and Greenland, native and white, but something over 100,000,000 people of the Soviet Union. They outrank us in northern population about 500 to 1."

ONE must not think, however, that Dartmouth men with northern hurricanes in their blood streams can think in hothouse terms. Their spirit is opposed to letting the Arctic go by default. If the Soviets can colonize the polar regions, Dartmouth men know that Americans can do at least equally well.

This is the belief also of the amazing 73-year-old explorer, Canadian born of Icelandic parents and American educated and Arctic tested, Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Ph.D., Litt.D., LL.D.

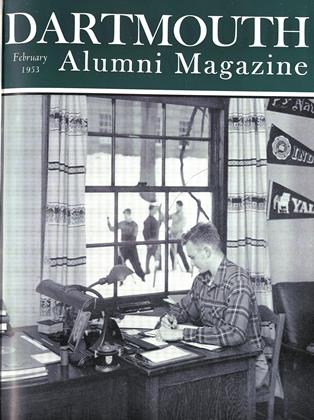

Dr. Stefansson, Arctic Consultant to the College for the past five years, has enabled Dartmouth to have the benefit of one of the greatest libraries in the world on the polar regions the personal library he has assembled by a lifetime of painstaking effort. It rests now in a special section of Baker, the envy of many, indeed of all, institutions of higher learning, 25,000 volumes, 20,000 pamphlets, and innumerable manuscripts about the Arctic.

There he works, and so does Mrs. Stefansson. Together they sort, type, catalogue, file, and talk with faculty and students and scholars from all over who come to take advantage of the magnificent research materials.

Stefansson feels that Dartmouth is the right place for young men to consider what they may do about the world of tomorrow in the Far North.

They can see what aptitude they have for a polar life, because Dartmouth College owns Mt. Moosilauke only 45 miles from Hanover which has arctic conditions. It owns also the top of Mt. Washington, which is being used as a base for research. It owns an extraordinary collection of maps and atlases.

For one reason or another a number of arctic specialists have gravitated towards Dartmouth, and they affect the lives of undergraduates. Commander David Nutt '41, USNR, Arctic Specialist at the Dartmouth College Museum, takes several Dartmouth students each summer in the Blue Dolphin to Labrador for oceanographic and hydrographic investigations under the joint auspices of Dartmouth College, the Arctic Institute of North America, the Office of Naval Research, the United States Navy Hydrographic Office, the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and Cornell University. Last March he and a student assistant returned to Goose Bay, Labrador, to continue these investigations under winter conditions.

Dartmouth has a number of scholars who have done work on the Arctic. Prof. Robert A. McKennan '25 spent a year 1929-1930 in Alaska among the Northern Athapascan Indians on the Xanana River and the summer of 1933 at the head waters of the Chandalar River north of the Arctic Circle. As an officer in the Air Force he helped to set up the Siberian ferry at the time the United States was ferrying fighter planes to the Soviet Union, then our ally. As Chief of Research and Development of the Arctic, Desert and Tropic Branch of the Air Force during the last year of the war, Lieutenant Colonel McKennan was with Brad Washburn testing arctic equipment on the side of Mt. McKinley.

Other outstanding specialists at Dartmouth are Prof. Trevor Lloyd, who has spent a year in Greenland and has made a life-time study of the geography and administration of Canada, Greenland and Arctic Scandinavia; Elmer Harp, Assistant Professor of Sociology, whose work in American archaeology has included "digs" in both Labrador and the Upper Yukon; Prof. A. H. McNair, who is engaged in researches on the geology of Devon Island in the Canadian Arctic; Prof. Millett Morgan, an authority on wave propagation in auroral regions; Dr. Hannah T. Croasdale, Associate in Zoology, who has published learned articles about the botany of Northern Alaska; and Richard H. Goddard, '20, Professor of Astronomy and Director of the Shattuck Observatory, who has spent a winter in Greenland and Baffin Land making investigations about terrestrial magnetism.

Whether the need creates the man with mind and power or whether the man with mind and power points up the need and the possibility of fulfilment may often be difficult to determine, but Stefansson, that "Prophet of the North" as his biographer calls him, has been for decades what Isaiah Bowman, former president of Johns Hopkins University, called the great interpreter of the Arctic. As such. Stefansson has been preparing the world for the past quarter of a century for what now seems to be taking place. He is peculiar in that despite his vast erudition and his incredible experiences in the lands of snow and ice, he does not wish to sit down and merely reminisce and dream out loud about the good old days.

He looks forward to the future, and he is making possible careers for the young explorers and colonizers. He has the experience, 40 years of passionate study and thought and ten full years of arctic field work, to guide the ambitious who wish to follow after.

No Hollywood hero who likes sensational flirtings with death in blizzards and on ice floes, Stefansson is a serious educator and a scientist. His main thesis is that the Arctic is no inferno in reverse and that arctic winters need not be insufferably cold with perpetual dangers. Positively, the Arctic can be a pleasant and almost limitless area for colonization and expansion with almost limitless wealth and power.

What the United States, and in particular colleges like Dartmouth should do, according to Stefansson, is to produce leaders for northern development. The opportunities are known to be great and may well be greater than anyone knows. Alaska and the Canadian Yukon have long been famous for gold, Greenland for cryolite, a mainstay of the aluminum industry. Government agencies are developing oil in the Alaskan Arctic and private enterprise is doing the like for the Canadian Arctic. Among the other known resources are platinum, copper, iron, fur and reindeer; whaling, sealing and fishing have already brought their rich harvests to the world market through more than three hundred years. The lumber and pulpwood of the Alaskan and Canadian North are on our immediate commercial horizon. The commonest thought of the specialists is that the riches of the unoccupied lands beyond our present northern fringe of colonization are no more than beginning to be suspected.

The Soviet Union, across that Mediterranean Sea of the future, matches all these products in quality and probably in quantity. What is the X and the sixty-four billion dollar question in these days of machines and transportation is oil. The United States and Canada would like to know how much the Soviets are pumping out and refining in their Arctic, and the Soviets are sure that no matter how much they have, they could use the Alaskan and Canadian wells with great advantage for the "workers" and the "people" and incidentally for their air force.

American and Canadian businessmen, educators, and military leaders all agree that there is work to be done in the Arctic, work by trained college men.

The fields of glacial geology are wide open, and the fields of petroleum and mineral deposits have just begun to expand. In anthropology we have still a lot to learn about the adjustment of Indian and Eskimo groups to white men's culture; and though we have learned much about diseases and nutrition and language among the forest Indians and Eskimos, we have far more to learn.

ABOUT 700 miles beyond the Arctic Circle, at Thule, Greenland, the U. S. Air Force has built an air base costing $263;000,000. We hear much talk of war these days. It may well be true, as military strategists suggest, that the North Pole will become the center of military activity if World War 111 breaks out. But who will admit that it is inevitable? If we can maintain peace, the Soviet Arctic will continue to bustle with economic activity and presumably with an economic prosperity which will impress countries on both sides of the Iron Curtain. Dartmouth men would be sorry to see the American Arctic go by default with consequent loss of prestige for the United States and Canada.

Fortunately Hanover is so located that it can provide many kinds of training. We have a medical school and a hospital. A future arctic physician can specialize in such matters as arctic parasitology, frostbite and freezing, nutrition and malnutrition, body temperatures and clothing all sorts of problems in cold-weather physiology.

We have an engineering and business school. There is much to be done in cold weather training: the logistics of equipment and supplies for expeditions and the construction of shelters; radio; mountaineering; maps, and map analysis.

We have a liberal arts college with specialists in anthropology, sociology, and economics; in geography and language; in geology and meteorology.

David Nutt and his students have hardly begun the immense task of oceanographic research needed by the United States and Canadian Governments. They are only a little way along the Labrador Coast.

Engineers, architects, mechanics, aviation experts of all kinds, linguistic experts, businessmen, doctors and dentists the list is long. A new civilization on a new frontier is opening up, and a young man at Dartmouth with a special aptitude and a special sort of imagination need not worry about a future where jobs are scarce, life dull, and careers uncertain.

As professors polish off their spectacles and retreat into the warm and dark recesses of alcoves for research and writing, they envy their students to whom the future really belongs. If the students have the Stefansson Lbrary and Baker for useful theory, they have for practice Bartlett lower and Holt's Ledge in Lyme to scale. (Between classes, a startled professor discovered two future explorers, aged 19, crawling around the narrow ledges of Webster Hall and clawing into the brick to keep their balance.)

Moosilauke and Mt. Washington loom white and enticing under northern stars and beckon young men to the polar regions. Hunters head for the Dartmouth Grant. Innumerable chubbers, packs on backs, hike to distant Outing Club cabins. Skiers find that the Hanover ski jump is too tame, and Suicide 6 too safe.

A large group heads north to the Laurentians in Canada, via Stowe. It is not much farther either in distance or time to head into a bright American-Canadian future. Even now it is not too late to dream of a free civilization emerging in the North Polar regions a free civilization made healthy and prosperous through science, training, courage, and imagination.

That is the sort of competition which Dartmouth men by training and tradition have always loved to meet.

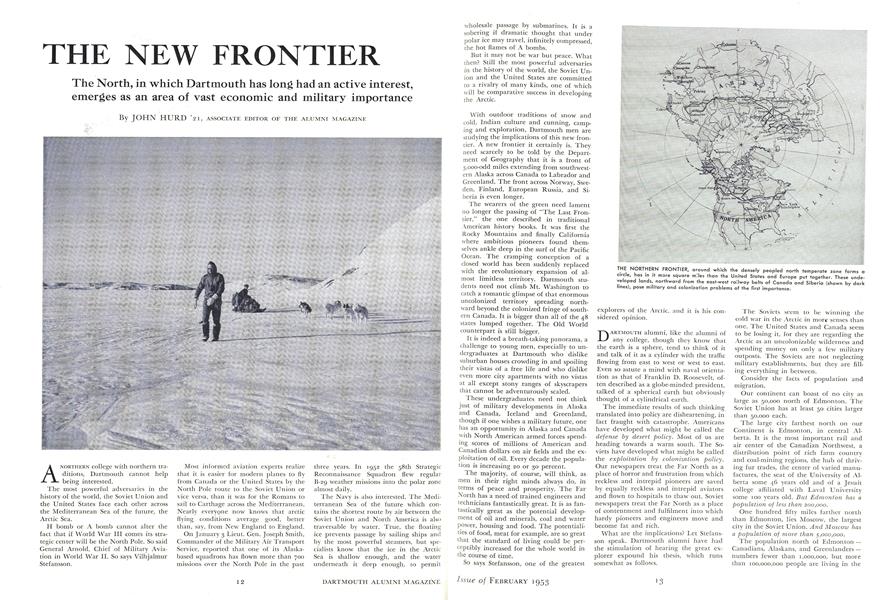

THE NORTHERN FRONTIER, around which the densely peopled north temperate zone forms a circle, has in it more square miles than the United States and Europe put together. These unde- veloped lands, northward from the east-west railway belts of Canada and Siberia (shown by dark lines), pose military and colonization problems of the first importance.

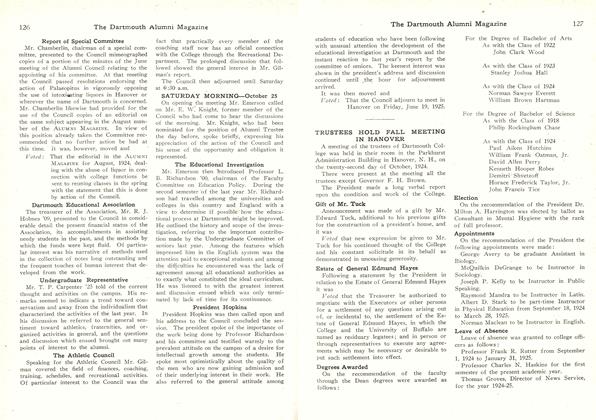

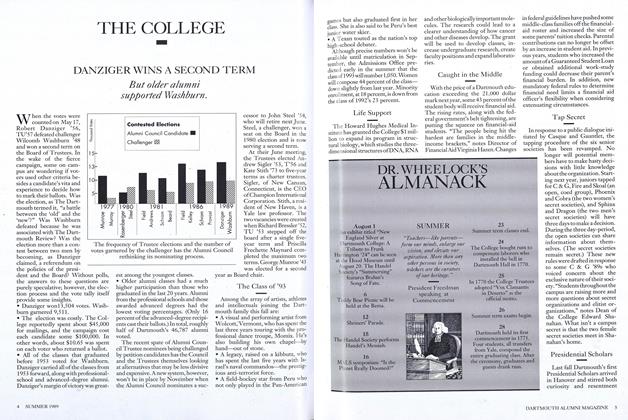

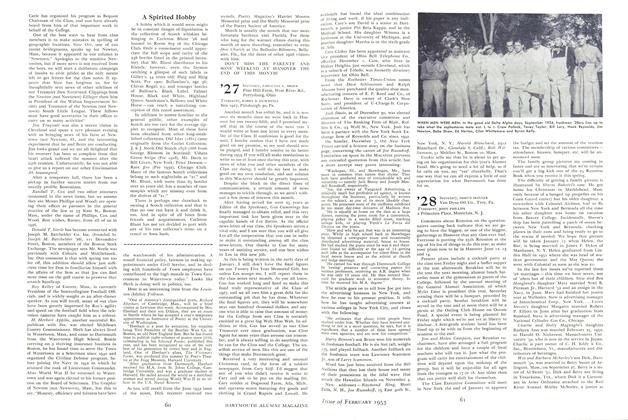

SUMMER SCENERY OFF THE COAST OF LABRADOR: An iceberg photographed from the "Blue Dolphin/7 the 100-foot schooner which, skippered by Comdr. David C. Nutt '4l, Arctic Specialist in the Museum, and manned largely by a Dartmouth crew, has made four summer expedttions to northern waters for oceanographic and hydrographic studies.

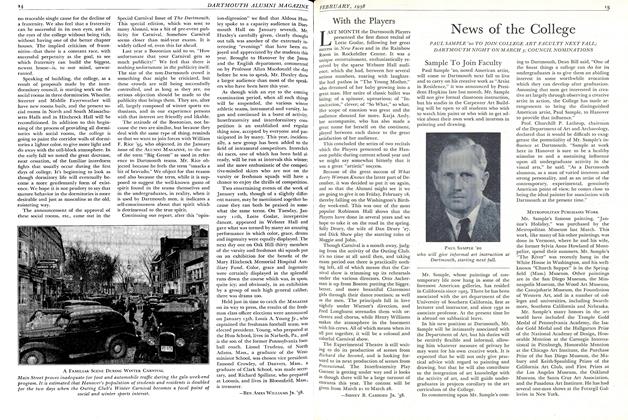

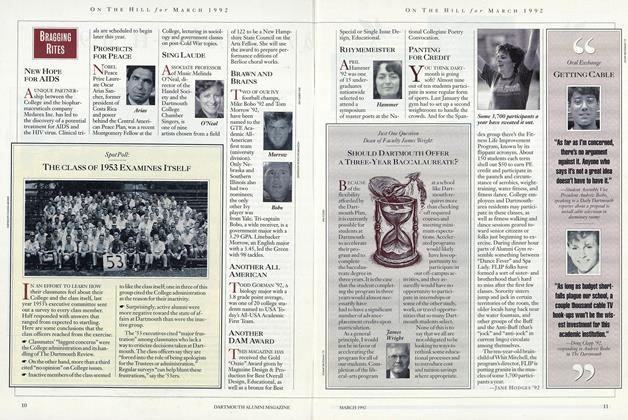

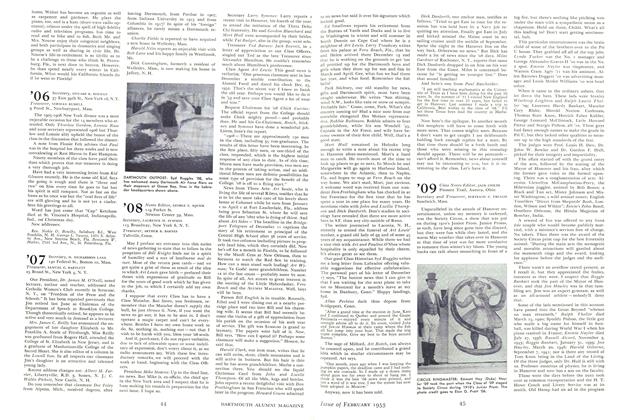

A WINTER COUNTERPART cf the summer expeditions of the "Blue Dolphin" was this field trip to Goose Bay, Labrador, last March by Commander Nutt (right) and John T. Tangerman '53, shown on the ice of the bay where they camped and set up a station for oceanographic observa- tions paralleling those made by ship in the summer. This winter work by the Dartmouth pair was a pioneer effort, calling for special methods and equipment developed in Hanover.

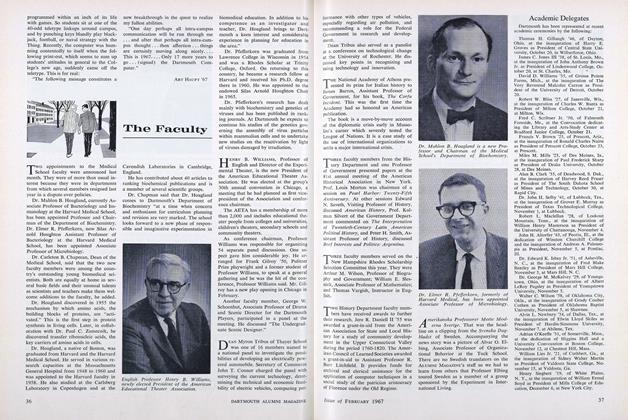

ViLHJALMUR STEFANSSON, Arctic Consultant at Dartmouth, and Mrs. Stefansson shown in Baker Library at ;he time of the uncrating and shelving of the famous Stefansson Library on the Arctic wh ch gives Dartmouth an incomparable asset for the study of the North. Mrs. Stefansson now serves as Librarian of the Stefansson Collection.

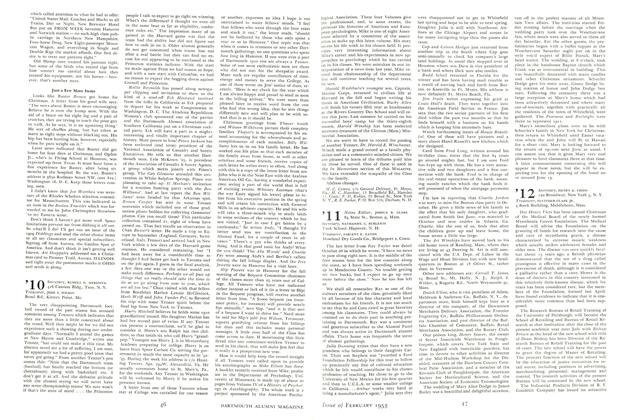

WINTER FIELD WORK FOR DARTMOUTH UNDERGRADUATES: Left, as part of the Dartmouth Outing Club's program of cold weather siudies, students under the expert tutelage of Vilhjalmur Stefansson construct a snow house on a farm near the campus. Right, John Tangerman '53, on the iced-over Connecticut River, tests some of the oceanographic instruments to be used on the Dartmouth winter expedition to Goose Bay, Labrador.

ASSOCIATE EDITOR OF THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe First Five Years

February 1953 By JAMES P. POOLE '28h, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

February 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

February 1953 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Class Notes

Class Notes1928

February 1953 By OSMUN SKINNER, JOHN PHILLIPS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1908

February 1953 By GEORGE E. SQUIER, LAURENCE M. SYMMES, ARTHUR B. BARNES -

Class Notes

Class Notes1910

February 1953 By RUSSELL D. MEREDITH, JESSE S. WILSON

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

ArticleHanover's First Aid Maestro

December 1942 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleMan on the Job . . . for Thirty Years

October 1950 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksLANDMARKS: A BOOK OF SONNETS AND OTHER POEMS.

October 1954 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE OFFENSIVE GOLFER

FEBRUARY 1964 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE NIGHT BOAT.

MAY 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBull Market

September 1975 By JOHN HURD '21