THE KOREAN WAR continues, and so does Dartmouth College. It is under full steam. Three thousand men respond to a thousand stimuli to brawn and brain. They do not come from the autumn alone, although old-timers say that they have never seen such brilliance in the conflagrations of yellow and red, gold and crimson, lemon and rose which stipple in gigantic splotches the sumac and maples, the birches and oaks.

For a freshman it is different. He speaks rather of people and buildings: the reflection of himself in a dorm mirror with a beanie on his head, the first grip of the hand of a roommate never seen before, and the enchantment of Dartmouth Row and the gym where during four years he is free to compete in his own way for athletic and academic success and happiness.

If moved by a united idealism, three thousand young men can furnish a spectacle which will generate faith in the most disillusioned alumnus. They were moved at Convocation when John Dickey spoke. Comfortable they certainly were not. Webster was—well, if you must know, pullulating with students. They sprouted forth from walls, they budded from beams, they proliferated from pillars, they exfoliated from balustrades. But even if intertwined and interwoven, they were certainly intent on the President's address.

Yet it was not oratory, bland and foamy. Here were not the usual phrases about hail-fellow-well-met, about the organ music of winds on Mount Moosilauke, and about the Gallant Green marching forward to Glorious Destiny. The words were measured and somber; the ideas, serious and exploratory. The President was asking, as well as explaining in words chosen as carefully as they were weighed, what were the place of free men and the nature of their responsibilities in Hanover, the United States, and the World. It was the sort of speech which cannot be reduced nicely to a paradox, rounded with an epi gram, made pungent with a witticism.

You will find the address in full on another page. What concerns us here is the applause, sincere and prolonged. It lasted longer than that of any heard by many older members of the faculty. One year out or fifty, a Dartmouth alumnus might have been moved by this particular form of college spirit.

THIS is not to say of course that the undergraduates emerged grimly from Webster to form parades carrying banners flaunting DARTMOUTH MEN ARE RE- SPONSIBLE and DARTMOUTH MEN ARE VERY EARNEST.

Class spirit and college spirit hardly manifest themselves in this way. In Hanover they come fuming up in Vox Pops. They sizzle forth from editorial pages. They bluster and blast from replies.

The Dartmouth of October 6 lambasts the freshmen in these words: ". . . something is radically wrong with class spirit among the '55's." In the same issue appears a letter to the editor signed by 20 undergraduates: "What has happened to our illustrious Vigilantes? We have observed a notorious lack of spirit among the class of 1955. Could it be that the Vigies are afraid to carry out their traditional duties? A notable example of this indifference was the fact that only one Vigilante was seen wearing his hat at the rally Thursday night, and he was powerless to enliven the listless frosh."

You may say, "Oh well, the editorial policy of The Dartmouth is sometimes a bit eccentric. Wasn't it queer last year?" And you may say that 20 undergraduates are not many in a college of 2,618. But in the same issue appears a letter signed by 109 undergraduates blasting the apathy at the rally to send the football team off to Philadelphia and Penn. The letter deplored "the deadness of the crowd," the faint cheering, and the absence of 85 percent of the freshman class.

These 109 undergraduates felt that something should be done about this lack of Dartmouth spirit, and this is the letter which they agreed should be published to excoriate publicly the freshmen:

"The resounding trumpetings and boomings of a band; scattered cheers; a rustling of books at Baker; the freshmen, minus beanie or pin, cocking his head to listen, then returning to his studies; upperclassmen hurrying to the Inn corner, puzzled at a once-spirited undergraduate body's indifference.... Is this a Dartmouth send-off? Is this what the class of '55 and all future freshmen classes are led to expect?

"The answer is emphatically no!! "What is the cause of this lack of spirit? Is it the freshmen, the Vigilantes, the upperclassmen, the Dean, the President, the Trustees? Whoever or whatever the reason, this is a plea for a revival of the old Dartmouth spirit. 'Men of Dartmouth, set a watch, lest the old traditions fail.' "

Such an "absolutely false charge" wounded and angered 26 freshmen enough to break into print next morning. In six paragraphs of hurt vanity and angry selfjustification they used such words as "grossly unfair" and "absurd allegation", and they explained why they could not attend the Penn rally: they were taking physical tests and scholastic placement examinations. The 26 incensed freshmen rose to this climax: "Our conscience is clean, but the one question which we should like to ask in regard to this whole question of Dartmouth spirit is this: Where are theupperclassmen?"

Well, come to think of it, where were those upperclassmen? The sophomores mustered their forces the next night and made an appearance. At once a whisper slithered sibilantly under the elms—a whisper which slid back into the throat and became a rumble, a growl, a shout. Finally from scrambled voices was heard an articulate jungle howl: '55 up, '54 up, '55 . . . '54 . . . GRR . . . UPPP.

Out from the dormitories—the hour is midnight—popped the freshmen and gurgled with Niagara bubblings like champagne from giant magnums and spouted effervescently towards the Chapel. The bells, rung spasmodically and frenziedly, drew out juniors and seniors in various stages of pajamaed and overcoated disarray.

Then ensued the Battle of Bartlett Hill, that eminence rising so feet or so from the East Wheelock Street sidewalk in front of the music building across from New Hampshire Hall. Favorites? The freshmen, egged on and abetted, cheered and insulted, by upperclassmen remembering their youth. The final results? 600 men gaining successfully the summit and 600 men thrown from it . . . the greensward on Bartlett Hill looking as if 1,000 golfers had forgotten to replace their divots . . . freshmen and sophomores" singing in their showers at 3 in the morning with new feelings about class spirit .. . professors in class next morning facing yawns only a quarter suppressed and wondering if their assignments had kept the boys up too late or whether they themselves or the boys were duller this year than usual until they remembered, "Dear me, yes. Last night's brawl."

CERTAINLY a sign of increased college spirit this year is the large number of Vox Pops, some mature and well written, others hot headed and ambiguous. One letter signed by a freshman says that TheDartmouth should back Senator McCarthy, not attack him. It was his second letter. The first had been apparently so maladroitly worded that the editor had completely misunderstood the point. Well, this freshman is going to write nine themes in Freshman English, and his instructor will be very much surprised if at the end of the term in February the freshman will not be able to express himself more clearly.

It is somewhat surprising for a freshman to sound forth on political topics in TheDartmouth. More likely a senior will. Hanover is no longer a college when a President Wheelock travels by ox cart, when the Connecticut is a boulevard for the canoes of redskins, and when the bears, wolves, lynxes, and panthers come snuffing out to strangers. Dartmouth is now in touch with the outside world.

Seniors, whether they like it or not, are forced to match their wits against men who could hardly be called hothouse plants from ivory-tower conservatories. Seniors work out intellectually in the Great Issues Laboratory, where they find every sort of magazine and newspaper from the rankest (most luxuriant) reactionary brand to the most luxuriant (rankest) subversive on display. It might seem that a senior might be stunned with so much economic and political opinion. Where should he begin? "What's the pitch?"

The G. I. Laboratory takes care of such colloquial and praiseworthy inquiries by posting at the entrance every little while a suggested reading list. How do you stand on the Article of the Week Club of October 1? Put an X beside those you intended to read. Or, perhaps better, put an X beside those which entirely escaped your notice. Too bad they did. It would be fun for you on their basis to sound out a senior's opinion.

Here they are:

1. Sidney Hook. "The Dangers of Cultural Vigilantism." New York Times Magazine. Sept. 30.

2. Karl Schriftgiesser. "High Pressure Lobbying." The Atlantic Monthly. October.

3. "The Trial of Philip Jessup." TheNew Republic. Oct. 1.

4. Dr. Max Seham. "The Government in Medicine." The Reporter. Sept. 18.

5. "Interview with Robert Schuman" in U. S. News and World Report. Sept. 28.

A freshman in his idealism may dream of the beanies worn through generations and the grass untrodden on by first-year feet, but a senior in his realism may reflect on the thinking caps of distinguished Americans who have spoken off the record at Great Issues about problems about the feet of the multitude on the stony road of the future.

Four years of Great Issues have a little of the effect on seniors that Catholic cathedrals in Europe have on American unbelievers or Protestants. Tradition has hallowed the walls, and only foolhardy egoists will monologue too long and too fliply about their religious and political vagaries.

For a senior finds on the walls of the Great Issues Laboratory the pictures of the speakers who for four years have accepted in good faith the request of President Dickey to speak to the 500 or 600 men of the senior class about what they as citizens are going to face on graduation. These key men—scientists, statesmen, business leaders and scholars—left their laboratories, capitals, factories, offices, and studies to do the best they could in an hour. They would tell Dartmouth men candidly what are the problems to be faced and how they should best be solved. Busy persons though they all were, they stayed over to spend another hour next day answering questions asked by the seniors as a result of their study and listening.

Here are some of these names, and it would be a rash man who would maintain that a future Dartmouth doctor or engineer, lawyer or businessman, clergyman or professor would be worse off for having listened to them and asked them questions that were candidly answered.

1. Enders M. Voorhees '14, Vice President of U. S. Steel, on "What Management Wants and Why."

2. Isador Pickman, Regional Director of the International Fur and Leather Workers Union, on "What Labor Wants and Why."

3. James Bryant Conant, President of Harvard University, on "Understanding Science."

4. Chester I. Barnard, President of the Rockefeller Foundation, on "International Control of Atomic Energy."

5. Thomas K. Finletter, Secretary of Air, on "World Government."

6. Charles Malik, Minister from Lebanon, on "The Problem of East and West."

7. Dean Rusk, Assistant Secretary of State, on "The Position of the United States on Foreign Policy."

8. A. S. Mike Monroney, U. S. Senator from Oklahoma, on "Effective Federal Government in a Free Society."

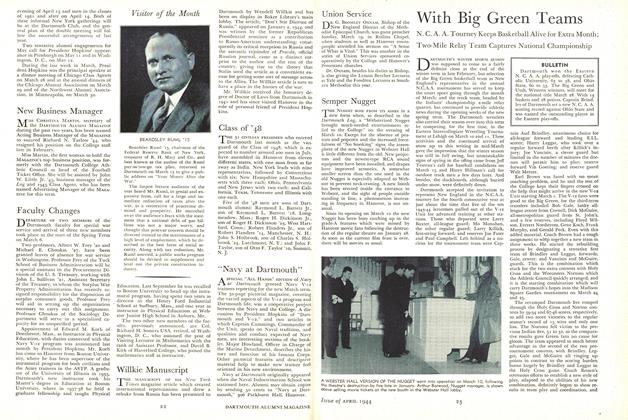

9. Beardsley Ruml '15, Former Chairman of the Board, R. H. Macy & Co., on "Some Issues of Choice and Duty."

10. Theodore M. Greene, Professor of Philosophy at Yale University, on "The Arts and Human Values."

11. Reinhold Niebuhr, Dean of the Faculty of Union Theological Seminary, on "Relativism and Absolutism in Ethics."

12. Nelson A. Rockefeller 'go, Chairman of the Advisory Board on International Development, on "Point Four in a Chaotic World."

The informal photographs of these leaders in our country—and there are many more who come to Great Issues—help seniors to feel that there are heights to be stormed outside Hanover.

It is no wonder that they look older than freshmen. The seniors are setting a watch for one set of values; the freshmen, another. If the old traditions do fail for the freshmen, there can be a fresh set of Vox Pops. If they fail for the seniors, they may have no voices to express, no newspapers worthy of the name, no Dartmouth College, and perhaps not even a world free from steel curtains heaven high and hell deep. The one about the United States would have extra thickness and steel of special forging.

THE Korean War continues, and so does Dartmouth College. And what of this war which so many fear may grow into an Asiatic one of bigger scope before it becomes smaller? It certainly impinges on our liberal college. Though Hanover looks normal with an undergraduate enrollment of 2,618 men, approximately the same as last year's (total enrollment of 3,783 is down 30 from last year's), and though the freshman class is the largest in history, 754, there are enormous and obvious differences between this year and last.

Last year we had only a Navy ROTC unit. Now we have Air Force and Army units also. Here are the figures, and one may see how large the military is going to loom up in the lives of future students. The Navy has 340 students enrolled, of whom 121 are freshmen; the Army 234, of whom 117 are freshmen; the Air Force 520, of whom 342 are freshmen; total 1,094 students of whom 580 are freshmen.

From now on, for how long no one knows, the Dartmouth curriculum must be altered. Long and earnest conversations are going on among members of the faculty about the impact of the military on Dartmouth as a liberal arts college. The magnitude of the problem will be suggested, though the full consequences hardly appreciated at first glance when one realizes that because the Armed Services require three hours of military science each semester, 24 hours of the 122 necessary to graduate a man, many elective courses must be foregone. Yet often these elective courses, though not a part of a man's major and often far removed from it, are among the most valuable to him of his college career. A future doctor may like a reading course in European fiction; a future engineer, a course in Oriental civilizations; a future business man, a course in Renaissance art; a future government official, a course in modern music. Students who love to diversify may find that they simply have not room to fit in the courses they long to take because their schedules are going to be so tight with required courses, majors, and military science.

It is not only possible but probable that one of the largest and best courses, English 51, Shakespeare, designed for both majors in English and non-majors, may suffer from a severe drop in enrollment because only majors will be able to fit it into their schedules. It is not only professors of English who would be sorry to find that future doctors or engineers or lawyers or businessmen at a liberal arts college with the standing of Dartmouth may not have more opportunity to study Shakespeare more intensively than they can in Freshman English when only two or three plays are read. Such cursory reading is only a tantalizing beginning for many ambitious students in their first years.

At the October faculty meeting President Dickey in welcoming the officers of the military units to Hanover called them colleagues. It is heartening to hear expressions of admiration from them about the ambitions of a liberal college. They like wide diversity, they say. So far from being shocked that Shakespeare is a good tonic for the morale and character of future officers, they would go even farther. At least the Colonel of the Air Force would. So impressed is he with the value of a Dartmouth education that he said that he would welcome the enrollment in the Air Force Unit of a student who had majored in Greek. Yes Sir, a Greek major could be used by the Air Force with advantage to it and the country.

But few persons will be so Utopian as to think that with all the politeness and good will (and there is plenty at the moment) the problem of curricular adjustments at Dartmouth is going to be solved easily. A committee of the faculty has been formed to review courses, majors, and credits and to explore all the ramifications of the new system which is going simultaneously to produce future officers for twentieth-century warfare and good citizens. It would be hard to think of a faculty committee appointed in recent years with a greater responsibility to the College than this one.

BUT SO far, so good. In a world where everything seems to be changing and nothing remains the same, the more Dartmouth changes, the more Dartmouth it is. The pealing of the chapel bells on October 13 flooded the fall foliage with the music of a football victory over Army, and a Sunday sports writer remarked that though Dartmouth had lost most of its best men by graduating, it had an aggressive outfit which could think smartly and act quickly on a rival's errors and on their own successful maneuvers.

Though football is only a game and studies and life have different values and goals, one need not fear too much a false analogy to say that all undergraduates, like all football players, must be more than machines; they must be mentally alert with experience enough back of them to make right decisions when opposing powers are making wrong ones under trying and unique situations.

But good judgments are rare in a confused world, and truth is elusive. Even about what seems so admirable a project as Great Issues, alumni may hear from seniors adverse criticisms which border on the rash or even the hysterical. Yet it is not surprising that a future engineer or doctor or research man in chemistry putting in long night hours on his work may squawk at the requirement of Great Issues. Some do, and loudly. But is not a specialist the very person who ought to be made aware of world problems in an era when too little leadership is found and too much ignorance and demagoguery?

Yes, definitely, says Dartmouth. She is not alone. Educator after educator has come here, listened to the Monday evening lecturer in Great Issues; afterwards from 10 to midnight over light refreshments listened to the discussion among a dozen professors and members of the college administration at the President's house; and next morning listened to seniors rise up and in Harvard LaW School fashion question the celebrity of the night before about what he said in his talk or in his articles and books.

So impressed have these visiting educators been that Great Issues have sprung up all over the country. If Dartmouth's Great Issues reputation has been national, it is about to take on an international tinge. The Voice of America is planning to broadcast to Europe a program about life at Dartmouth: a democratic college in a democratic country.

It seems almost inevitable that the broadcast will stress what is so important for Communist-flanked Germany to know. The President, the Board of Trustees, and the Faculty attempt to encourage Dartmouth students to think for themselves and to develop a sense of responsibility to complement their sense of freedom. Dictatorship is out.

Robot students are not good enough for Dartmouth; robot citizens are not good enough for the United States; a robot Asia is bad for the world. In an enlightened and free America and Europe lie the best hopes of humanity in a world increasingly administered by brutal dictators.

AS MUCH OF A FALL STAPLE AS GOLDEN LEAVES ARE THE TOUCH FOOTBALL PLAYERS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1951 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleA Free Man Is Answerable

November 1951 By President Dickey -

Article

ArticleTo the Top of McKinley

November 1951 By JERRY MORE 52. -

Article

ArticleMore Bone and Sinew For a Growing College

November 1951 By NICHOL M. SANDOE '19 -

Article

ArticleAmbrose White Vernon

November 1951 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

November 1951 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND

John Hurd '21

-

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN THE CARIBBEAN.

January 1960 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksWOODSMOKE AND WATER CRESS.

JANUARY 1966 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksHOW TO LIVE LIKE A RETIRED MILLIONAIRE ON LESS THAN $250 A MONTH.

November 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksYOUR JOB: TO HAVE AND TO HOLD.

NOVEMBER 1971 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleGREEN HIGHLANDERS AND PINK LADIES.

MARCH 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBIG BUSINESS – YOUR LIFE WITHIN IT.

October 1974 By JOHN HURD '21