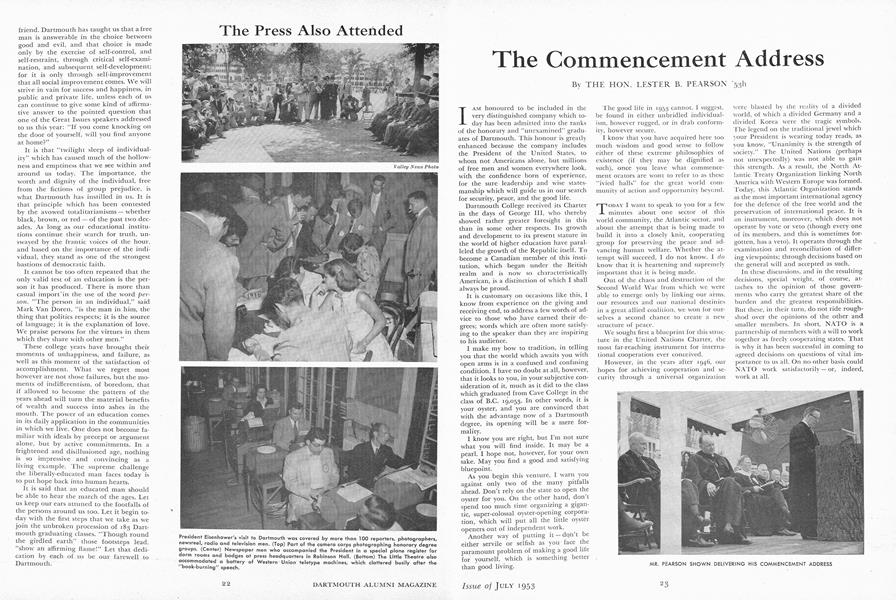

I AM honoured to be included in the very distinguished company which today has been admitted into the ranks of the honorary and "unexamined" graduates of Dartmouth. This honour is greatly enhanced because the company includes the President of the United States, to whom not Americans alone, but millions of free men and women every where look, with the confidence born of experience, for the sure leadership and wise statesmanship which will guide us in our search for security, peace, and the good life.

Dartmouth College received its Charter in the days of George III, who thereby showed rather greater foresight in this than in some other respects. Its growth and development to its present stature in the world of higher education have paralleled the growth of the Republic itself. To become a Canadian member of this in stitution, which began under the British realm and is now so characteristically American, is a distinction of which I shall always be proud.

It is customary on occasions like this, I know from experience on the giving and receiving end, to address a few words of advice to those who have earned their degrees; words which are often more satisfying to the speaker than they are in spiring to his audience.

I make my bow to tradition, in telling you that the world which a waits you with open arms is in a confused and confusing condition. I have no doubt at all, however, that it looks to you, in your subjective consideration of it, much as it did to the class which graduated from Cave College in the class of B.C. 19,053. In other words, it is your oyster, and you are convinced that with the advantage now of a Dartmouth degree, its opening will be a mere formality.

I know you are right, but I'm not sure what you will find in side. It may be a pearl. I hope not, however, for your own sake. May you find a good and satisfying bluepoint.

As you begin this venture, I warn you against only two of the many pitfalls ahead. Don't rely on the state to open the oyster for you. On the other hand, don't spend too much time organizing a gigantic, super-colossal oyster-opening corporation, which will put all the little oyster openers out of in dependent work.

Another way of putting it - don't be either servile or selfish as you face the paramount problem of making a good life for yourself, which is something better than good living.

The good life in 1953 cannot, I suggest, be found in either unbridled individualism, however rugged, or in drab conformity, however secure.

I know that you have acquired here too much wisdom and good sense to followeither of these extreme philosophies of existence (if they may be dignified as such), once you leave what commencement orators are wont to refer to as these "ivied halls" for the great world community of action and opportunity beyond.

TODAY I want to speak to you for a fewminutes about one sector of this world community, the Atlantic sector, and about the attempt that is being made to build it into a closely knit, cooperating group for preserving the peace and advancing human welfare. Whether the attempt will succeed, I do not know. I do know that it is heartening and supremely important that it is being made.

Out of the chaos and destruction of the Second World War from which we were able to emerge only by linking our arms, our resources and our national destinies in a great allied coalition, we won for ourselves a second chance to create a new structure of peace.

We sought first a blueprint for this structure in the United Nations Charter, the most far-reaching instrument for international cooperation ever conceived.

However, in the years after 1946, out-hopes for achieving cooperation and security through a universal organization were blasted by the reality of a divided world, of which a divided Germany and a divided Korea were the tragic symbols. The legend on the traditional jewel which your President is wearing today reads, as you know, "Unanimity is the strength of society." The United Nations (perhaps not unexpectedly) was not able to gain this strength. As a result, the North Atlantic. Treaty Organization linking North America with Western Europe was formed. Today, this Atlantic Organization stands as the most important international agency for the defence of the free world and the preservation of international peace. It is an instrument, moreover, which does not operate by vote or veto (though every one of its members, and this is sometimes forgotten, has a veto). It operates through the examination and reconciliation of differing viewpoints; through decisions based on the general will and accepted as such.

In these discussions, and in the resulting decisions, special weight, of course, at-taches to the opinion of those governments who carry the greatest share of the burden and the greatest responsibilities. But these, in their turn, do not ride roughshod over the opinions of the other and smaller members. In short, NATO is a partnership of members with a will to work together as freely cooperating states. That is why it has been successful in coming to agreed decisions on questions of vital importance to us all. On no other basis could NATO work satisfactorily or, indeed, work at all.

The solemn covenant to which the Atlantic governments subscribed in 1949, the steady progress which has been made in strengthening our defences, and in developing the institutions and practices of Atlantic cooperation, are among the most remarkable developments of a remarkable era.

Striking as this development has been, we should not forget that if the Atlantic coalition remains merely an improvised reaction to postwar perils, a by-product of a cold war, it is not likely to survive the emergency which created it. Its foundations must go deeper than that. They must reflect the enduring links which bind the old world and the new. I think that they do.

The Atlantic peoples have common traditions and spiritual values derived from the same ancient sources. There has long existed a natural and permanent foundation for a community of interest and action. Over many centuries through exploration, through settlement, and in peace and in war, we have drawn not only the material elements from a common civilization, but, more important, the same basic principles of social and political belief, the same fundamental freedoms of speech and worship, the same practices of tolerance and respect for the rule of law, and the same in destructible belief in the inherent worth of the individual and his right to freedom. Fear is not the only thing holding us together.

IT is not, however, easy to live and work in a world whose future is darkened by the lengthening shadow of man's growing capacity for self-destruction. It is not easy for free democracies in peacetime to devote large proportions of their energies and resources to defence. It is not easy to maintain an "alert" which in the nature of things must last for many years. Nor is it easy in the absence of all-out war for proud and sovereign states, whether great or small, to adapt their national policies to the wider interests of a larger international community.

It is only by identifying and taking the measure of these difficulties that we can combat and overcome them. To ignore them, to pretend that they do not exist, would be to jeopardize the great task to which we have put our hands. Certainly the disciples of the philosophy of world domination know that they exist, and are determined to do everything possible to exploit and exaggerate them, in the hope that they will ultimately destroy the unity we have achieved and which they fear so much.

Since the death of Stalin, our coalition has also had to face a "peace offensive." This may bring its opportunities, which we should exploit. But it may also bring new tests and even dangers which, on our part, will call for steadiness and patience. We know that military force, or the threat of it, is only one of the weapons in the armoury of those who would seek to achieve world domination. There are other weapons, less obvious but no less powerful, which will be employed in the hope of dividing us.

One of these is the economic weapon. We must see to it that disunity arising out of economic nationalism does not do the job that military force has so far been unable to do. Here too we must "go it together." There would be no surer way to dismember our coalition than to permit the flow and volume of trade between the free nations to start on a downward spiral with countries again resorting to extreme restrictive measures against each other. The success of the free world in solving its economic problems may, in fact, be of decisive importance in the struggle against Soviet imperialism.

In resisting this evil Communist combination of military might, political in-filtration, economic and psychological pressure, we do not forget that along with the external threat of Communism there is also the internal threat of subversion which requires an equal vigilance and, wherever necessary, effective action to counteract it. If, however, we were to exaggerate this internal threat, and in meeting it, if we were to abandon or weaken in our adherence to well-tried principles of justice and the rule of law, of tolerance and understanding, which are the basis of. the democratic tradition, we should find only that we had created a tyranny in defending ourselves, against one. We must not compete with Communism in elevating fear in to a civic virtue, in making denunciation the test of loyalty, in exalting violence as a badge of patriotism, or in making sterile conformity the test of good citizenship.

Nor is this the only pitfall. In each country of the coalition especially in those which speak the same language

voices are raised in our midst, calculated to exaggerate the differences which arise between us. Irresponsibility of this kind can undermine the mutual understanding on which our community rests.

As a Member of Parliament, I may refer, without impropriety I hope, to what Lord Acton has described "the never-ending audacity of elected persons." Some of this verbal audacity on both sides of the Atlantic consists of appeals to passion and prejudice by men whose horizons are circumscribed only by their own ambiguous purposes. We will be wise, I think, not to confuse these sounds with the voice of the people, or to mistake calculated and theatrical outbursts for frank and honest criticism.

But perhaps the greatest threat to the unity of the Atlantic coalition lies paradoxically—across the Pacific. New forces have swept across the Far East, some of them reflecting the pulsations of aggressive Communism, others related to the surge of nationalism which has marked the 20th century. We have been as one in supporting the principles on which we believe an honourable and just armistice can be arranged in Korea. Before us, however, there are new and challenging Pacific political problems so grave that, if we do not achieve agreement in our approach to them, our unity will be weakened and prejudiced.

The basic requirement, as I see it, is to recognize the distinction between Communist military aggression which, as members of the United Nations, we should always be prompt and united to resist; and Communism as a social, economic and political doctrine which, abhorrent as it is to free men everywhere, must be resisted and eradicated-by other means than bayonets or atom bombs. This can best be done by making our own democracy work, and assisting and encouraging Asian democracy to work, in ways which will do more for the welfare and happiness of men than Communism can ever hope to do.

With a sober sense of our responsibilities, then, with determination to understand each other's viewpoint, we must strive to harmonize our views on the Com- munist threat, and what to do about it, in this vast and crucial Asian area of the world.

THESE are some of the problems ahead for the coalition. Clean-cut solutions tor them are not always possible, and distant ones cannot be realized in the present. They present a challenge to us all. National action, moreover, is inadequate to the dimensions of this challenge. International action is essential and it must operate through consultation, persuasion, agreement. In such cooperation we have no alternative but to "go it together," in the clear knowledge of where we are going, how we can most surely reach our destination. and how much strength we can gather from each other on our journey.

As we march together, we may occasionally, because we are free men and not regimented sheep, get out of step. When we do so, of course, it is regrettable, and to be corrected as soon as possible; but it is far better than Communist unity where the leader relies on a pistol at the back to keep sullen or reluctant followers in line.

On the part of the United States, the acknowledged leader of our band of free countries, this "marching together" will require patience, consultation with her friends on direction and objectives, and, at times, concessions to their viewpoint.

For the other members of the coalition there is an equal and parallel obligation to recognize frankly and ungrudgingly the tremendous contribution to the common effort which the United States is making and the special responsibilities it has undertaken. We can best do this by making a full contribution to the common task, and by making our own concessions, when necessary, to common agreement.

Furthermore, we cannot be united in one area of the world and divided in an-other. No one has explained this better than President Eisenhower did at Minneapolis last Wednesday when he said:

"... there is no such thing as partial unity. That is a contradiction in terms. "We cannot select those areas of the globe in which our policies or wishes may differ from our Allies-build political fences around those areas and then say to our Allies: 'We shall do what We want here-and where you do what we want, there and only there shall we favor unity.' "That is not unity. It is an attempt at dictation and it is not the way free men associate."

Those are good and true words. They derive from the recognition of the fact that there is a strength in the cooperation of free men that slave societies can never hope to attain.

In this cooperation, difficulties of ten daunt us-and trials oppress. The long and hard ascent to friendship and better understanding between peoples of ten seems like the last 1,000 feet to the summit of Mt. Everest; a peak, incidentally, which was finally scaled by a Nepalese and an Anglo-Saxon working together; a Buddhist and a Christian.

In our slow march forward and upwards we meet frustrations and we have our setbacks. These, however, mean no disgrace, and are no cause for despair, as long as we do not allow them to drive us off our course or destroy our resolve.

If we, whose graduation date seems a depressingly long way behind us, falter in this striving for better things among and between men, well, the class of '53 will soon be on the scene in more than 53 free countries.

I know that you of the Dartmouth division of this great, reinforcing army, whatever the work that you are called on to do, whatever your responsibilities may be, will add your strength, your energy and your mind and heart to the effort that is being made in so many lands to bring peace and decency and some tranquillity to this tortured world.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

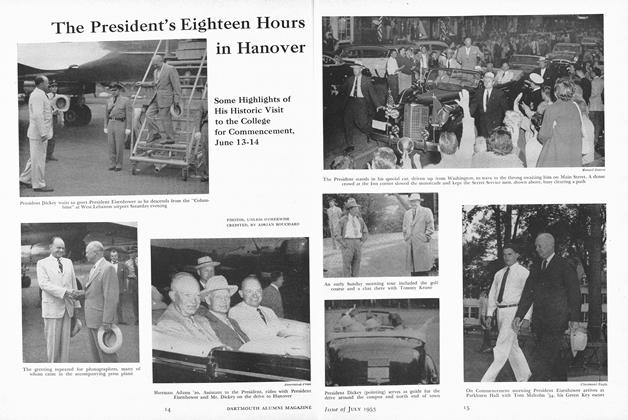

Cover StoryThe President's Eighteen Hours in Hanover

July 1953 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

Article

ArticleThe 1953 Commencement

July 1953 -

Class Notes

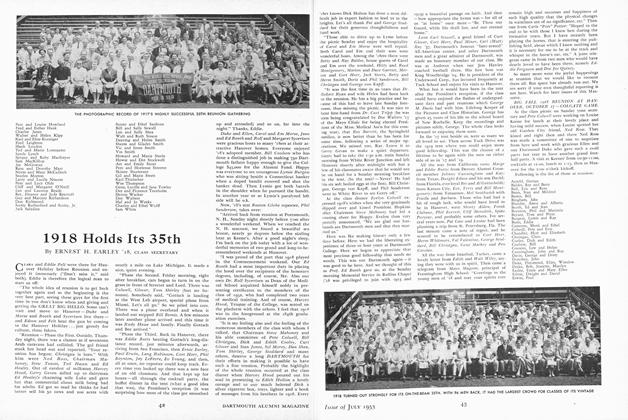

Class Notes1918 Holds Its 35th

July 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY '18, -

Class Notes

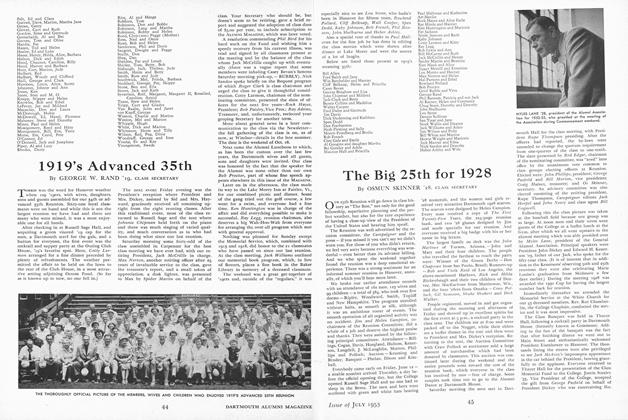

Class NotesThe Big 25th for 1928

July 1953 By OSMUN SKINNER '28, -

Class Notes

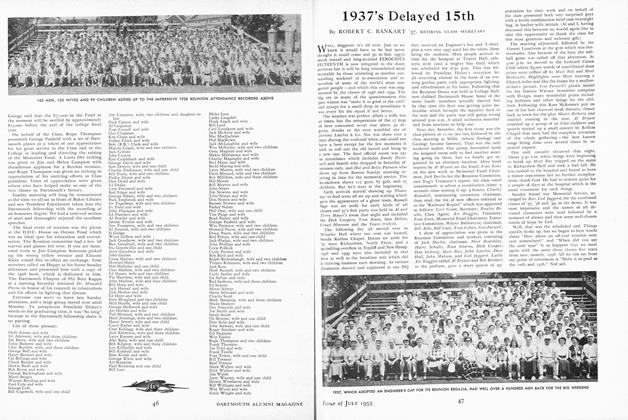

Class Notes1937's Delayed 15th

July 1953 By ROBERT C. BANKART '37 -

Article

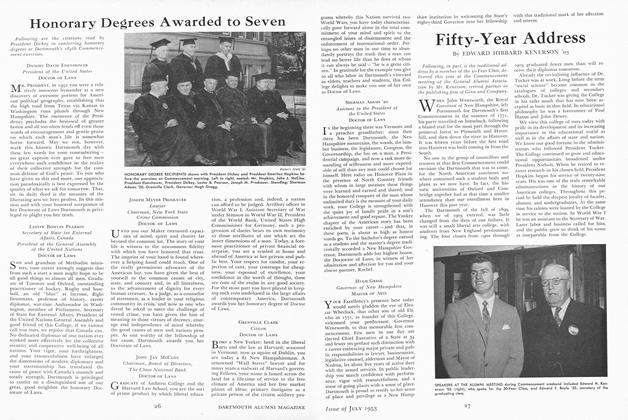

ArticleFifty-Year Address

July 1953 By EDWARD HIBBARD KENERSON '03