ONE year ago, a former editor-in-chief of The Dartmouth reviewed his last undergraduate year at Dartmouth, and communicated in these columns the sense of foreboding, of imminent military disaster, that then hung over him and his classmates.

Today, a somewhat younger senior has been called upon to survey the last few months in Dartmouth's history, as he sees them.

These months are history, for no sequence of helter-skelter events can have meaning unless they are incorporated into a larger Meaning, which in this case is the life of a timeless institution called Dartmouth College.

He sees these months as history, because that is part of the transition that he and 550 of his classmates are beginning to make. By the time this issue of the MAGAZINE reaches circulation, that transition will have gone through its better part. Four years of classroom duties will have been completed, and the occupants of those classrooms will be readying themselves to assume bigger duties, that come from privileges of alumnihood and adulthood.

This is no time for an Undergraduate Chair; four years is long enough to be an undergraduate, and eight months of an alumni magazine is too long for anyone to sit in a chair.

At various times during past international emergencies, a general feeling of terror has permeated the College community. Thus, in 1950, after the outbreak of the Korean War, student resignations and service enlistments reached all-time highs, and there was serious talk of summer sessions and accelerated courses. At Convocation that year, President Dickey commented that "this particular perch in the universe which we call Earth is rapidly becoming a precarious place for raising human beings." Warning that "if you must fight, the cause can be worthy of your best," the President saw "no probable prospect that this generation of college students can escape the heavy personal burden of bearing arms in their country's service."

Much of this stark pessimism continued through the next year and a half; thus it was that Kenneth J. Roman Jr. '52, writing in April 1952, could say: "The consequent effects of pressure have already been felt; and it is generally understood that they will be considerably worse in the future."

But in spite of this ominous forecast, the pressure on the Dartmouth undergraduate seemed to ease up this year. The three ROTC units, already established by June of last year, failed, after a desultory and vain attempt to convert the College Band to their own purposes, to exceed their given bounds. During the last days of the Democratic Administration in Washington, the Selective Service system managed to let everyone know how they stood, and panic enlistments stopped.

General easing of the world situation with Stalin's death and peace overtures in Korea, complementing a growing confidence in a more capable Administration, could not fail to have their effect on the Dartmouth student. Many, it was true, planned to enter military service after graduation. But many also planned to enter graduate schools or accept positions with the more than 103 firms a record number that sent representatives to the campus to interview seniors. Donald W. Cameron '35, head of the Placement Bureau, reluctantly had to admit to sixty other firms that "there just weren't enough men to go around." The reason: Many more seniors planned this year to continue their education, and others had definite schedules worked out for the military. More settled conditions seemed to be indicated.

Administration and student policy groups kept pace with the changing times. The "go local" movement was sparked by an IFC-sponsored poll which reached 80% of the fraternity men on campus early last month. Early tabulations showed an almost even split on whether dissolution of all national affiliations would be "to the betterment" of the College. However, a "considerable percentage" of the No vote indicated a willingness to go local if the rest of the campus would also do so.

Early last July, the "Ivy League" presidents met and announced a new agreement on football policy. Whether the strengthening of the once-loose football pact was a formalization of the "Ivy Group" was not immediately evident, but the stricter rules brought howls of protest from students in all eight colleges when school convened. A substantial local group lobbied for reinstatement of spring football, but no reversals were won.

Curricular and mechanical improvements occupied the Administration for much o£ the year. The library lighting was revamped, and a $50,000 gift instituted a new course in Human Relations. A little later, several other faculty departments got together and put the much-debated Science 12 course in the curriculum. The academic expansion program progresses further when, next autumn, a course-offering tossed about for five years reaches the lecture hall. "The Individual and the College," originally planned to replace Freshman Hygiene for the Class of 1953, will finally be offered to the Class of 1957.

The Undergraduate Council and the Interfraternity Council met routinely most of the year, but a few extraordinary rulings were released. Dean Neidlinger's old drinking system was revamped, and a whole new set of rules, including morning and Sunday curfews, went into effect. I-D cards, first lambasted by a moribund Jackolantern, came to be accepted after they worked a little too perfectly over a Winter Carnival that was at last "given back to the Indians."

Palaeopitus zigzagged and reversed, but experimentation with forms of freshman orientation brought positive results. A completely eased-up system produced only a spiritless Class of 1956 and an irate up-perclassman riot; so the black hats of the old Vigilantes were restored, but the power under them modulated. Selection of next year's "Freshman Orientation Group," a long and laborious process under the new rules (which call for "well-rounded men"), still continues.

If student disturbances are any indication of instability, the present academic year proved exceedingly stable. Only one big riot broke campus peace a well-meaning but misdirected demonstration for freshman class spirit. However, while Princeton was tearing Nassau apart late in April, an unfortunate incident hit the wire services, date-lined Hanover, N. H.

Several men yielded to the pesterings of an 8-year-old boy and fed him liquor through a dorm window. The unfortunate incident had unlucky repercussions, and, in spite of prompt and strict action by the Administrative and undergraduate judiciary bodies, town rumors flew, and distortions tortions appeared in the nation's press.

Financially, the biggest news in recent College history was the donation of $1,000,000 by an unknown benefactor for the establishment of twenty Daniel Webster National Scholarships. Locally, students viewed with more acute interest the progress of the artificial ice piping being installed in Coach Eddie Jeremiah's hockey rink. A hockey team worthy of the northern tradition was predicted immediately.

Undergraduates had flings, and the Administration winked knowingly as TheDartmouth (probably illegally) parodied the Harvard Crimson during the Boston football weekend. Floods of water from the snow-laden mountains caused floods of students to invade the new Dean's office just before spring vacation, and plead (successfully) for a cancellation of classes. Holy Cross undergraduates enjoyed themselves immensely here during a fall football fling, and returned a box of pilfered trophies to Hanover weeks later. Dormitories and a couple of fraternities went on and off social probation.

Franklin D. Roosevelt once paid Hanover a summer visit while he was President of the United States, and Taft and Wilson are reported to have been here while in office, but a visit by the President is still a great and rare event for Dartmouth —so it was understandable why College officials were pretty cagey about persistent rumors since January that Dwight D. Eisenhower was coming to speak in Hanover in June.

Drew Pearson apparently started the tall tales flying by an insignificant reference in a news column just after New Year's. At that time, nobody would make any comment. Private vate individuals and the press badgered officials, assistant officials, and secretariesonce-removed. But silence seemed the order of the day.

A routine release from the White House late in the evening of April 29 announced that President Eisenhower would receive an honorary Doctorate of Laws from Dartmouth at Commencement on June 14.

Students were tickled, and faculty members who hadn't been to a Commencement for twenty years dusted off their academic robes for the big day. The Bema, recently too small even for "non-distinguished" Commencements, was discarded in favor of the grass area in front of Baker Library. The Secret Service cased the joint, and Sherman Adams undoubtedly had a good laugh at Sinclair Weeks, who is a Harvard man.

The noisiest repercussion of the whole story was the whir of the four engines of the Columbine, as it practice-landed three times early in May at the Lebanon airport, just to be sure it could make it.

Individual students brought both fame and infamy to the College during the academic year. Sophomore Ralph Miller surprised the skiing world and himself by running away with just about every championship there was to win. A group of students pried the name plate off Senator McCarthy's door in Washington, and got themselves investigated, cleared, and awarded souvenir plaques. A sophomore raided the wrong dorm in Cambridge while on a fraternity pledge trip and found himself self in the firm embrace of the Boston police. Another Dartmouth man ran into trouble in the same town when he got himself arrested for "attempted assassination of Adlai Stevenson" during the campaign. In Fort Lauderdale, Florida, a group of Dartmouth men, lacking other transportation, ran off with a bus; while another group raised havoc with a large dead shark.

And the campus paper had two more flings before the year was out. The first was a nation-wide campaign to "Give Vermont Back to the Indians," complete with buttons, contributions, and Life coverage. And the second was the successful kidnapping of an entire shipment of mid-spring Jackolanterns. A campus treasure hunt turned up the hi-jacked copies in a dusty elevator shaft. The resultant publicity just enabled the dying magazine to make ends meet for the one issue, and a group of students began conferences to plan a new campus periodical.

But still girls' colleges found men from the Plain irresistible, and countless trips were sponsored to interject a little co-ed atmosphere. At least no one could say the men were not red-blooded: a Bloodmobile trip to Hanover turned out a record number of student donors.

The entire student body was exposed to a Great Issue on March 13, a privilege previously reserved for the seniors. President Dickey's talk on Communism outlined an aged institution's policy on a brand-new problem. Said the President: "A person who accepts the obligations of membership in a conspiratorial group, committed to the use of deceit and deception as a matter of policy in the pursuit of its ends, is basically disqualified for service in an enterprise which is squarely premised on the functioning of a free and honest market place for the exposition, exchange and evaluation of ideas."

President Dickey went on to say that "I possess no information which leads us to believe that any member of our faculty or staff is subject to the discipline of such a conspiratorial group." The talk was applauded locally, but there were national intimations that either the Velde or the McCarran committees would be in New England to study subversives in education. Of course the Manchester Union-Leader pointed out that this meant Dartmouth. But no investigators have as yet showed up.

Modern times crept up on the town, and a committee for TV study was set up by the College. WDBS pondered affiliation with NBC. And the townspeople voted funds for a visiting nurse service and a road grader.

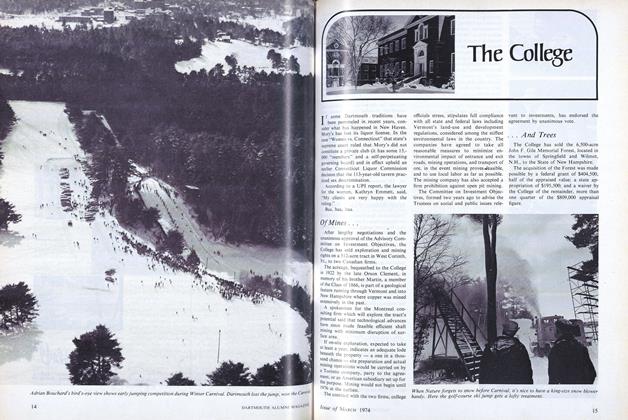

The weather was never predictable: snow fell on Fall Houseparties and two weeks before Green Key but there wasn't enough for Saturday of Winter Carnival.

An honor system was again pondered, and a referendum was planned for next fall. There were startling sports upsets (basketball over Holy Cross) and startling sports defeats (Holy Cross 99, Dartmouth 50 also in basketball). People played practical jokes on WDBS by jamming their air-waves and shipping them aluminum filing cabinets, and spring sports competition on the campus and final exams in the Alumni Gym came more quickly than most realized. The interfraternity hums went off as scheduled, and a student kicked his leg out of joint while teasing a dog in front of the Administration Building.

The year is done. Tradition —or at least consistency would dictate that we now turn back to that frame of reference we saw in September, when 2,837 undergraduates "rumbled up out of the valley and on to the plain," with Eleazar Wheelock welcoming the perennial arrivals from his Baker Tower perch.

We could not hope to show a change in Eleazar; he is still the same enigmatic bargainer for Truth that he has been in spirit for more than a century and a half.

But if we were to picture the seniors, rumbling down into the valley and away from the plain, they would not be the same men they were last September. Most of them would be reminiscing about their time at Dartmouth; all would realize what an Instant four years really was.

And as these men looked backward to last September and to a September four years ago, they would also be looking forward. Many more Septembers and many more undergraduates would pass under Eleazar's nose. And each new September and each new undergraduate would be the beginning of another transformation.

None would want to put that transformation into words; for a change from bewilderment to purpose, from childhood to maturity, is not easily located linguistically.

But all would realize that, whatever it was, that Instant with Eleazar had a lot to do with it.

And all would advise those many more undergraduates to come Catch that Instant while you can, for it's gone beforeyou realize what it's here for.

WHY THE FISH? Two Dartmouth d'plomas belonging to Sears and Jackson, of the Class of 1792, are decorated by a fish which has greatly mystified researchers. The diploma shown above was Joseph Sears'. The trumpeter is also an unusual feature, appearing only on these two sheepskins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

June 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

June 1953 By PHILIP K. MURDOCH., MARVIN L. FREDERICK -

Article

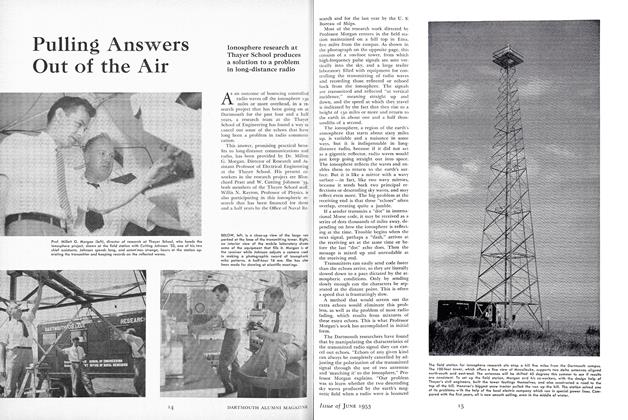

ArticlePulling Answers Out of the Air

June 1953 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

June 1953 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, GEORGE B. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1932

June 1953 By JOHN A. WRIGHT, JAMES D. CORBETT -

Article

ArticleHow Occom Pond Came Into Being

June 1953