The Seniors' Valedictory to the College

AFTER sixteen years of formal education, we have come today, curiously enough, to the most formal moment of all to end the formality. Ceremonies are important perhaps not in themselves but because they symbolize in a few brief words and gestures the meaning of what has gone before. More than that, they raise men up by reminding them not only of what they are, but what they ought to be.

Four years ago, when we "rumbled up out of the valley and onto the plain," we came from thirty-six different states, and from fourteen foreign countries to a Dartmouth that was but a name, and buildings on a map. Out of that rich diversity of background and experience we participated in the continual search for truth which has been the traditional position of this College since the day in 1771 when Eleazar Wheelock stood on this spot and conferred degrees by the authority of George III of England. Times change rapidly, for it was. but eighteen years later, in 1789, that George Washington directed a letter to President John Wheelock, citing the ideals, of this new democracy, and adding that "from this seminary, he and his fellowworkers were to derive great assistance."

In our own four years the change has been just as rapid, and accompanied too by tragedy. The senior class that we first knew bade farewell to the College "for a future unclouded by war," as was expressed at their Commencement. Within the month, war had come again, and the usual September greeting of "how was your summer?" had changed to anxiety over the war in Korea, and status with the local draft board. The meaning of that change in attitude was brought home to us early this year when we received the tragic news that one of the seniors who addressed that graduating class of 1950 had given his life in the seemingly unending struggle that freedom wages with thralldom. If there be one clear lesson we have learned from history, it is that "civilization is always on trial." With these maturing years has come a clearer recognition of the responsibilities of world leadership which this country has assumed, and for a future yet precarious and uncertain, we have learned to accept by inward responsibility the burden of military service which our generation must bear.

The most abiding possession that we take with us today from Dartmouth is a constant awareness of that inward responsibility. "What do I think of myself, and my responsibility?" is the question each of us is asking privately today. Perhaps what we have realized most of all is that evil is not so much out there in the world to be conquered, but quite as much within ourselves, when we sense the irreparable damage that we have done to a neighbor, or the wound that we have inflicted on a friend. Dartmouth has taught us that a free man is answerable in the choice between good and evil, and that choice is made only by the exercise of self-control, and self-restraint, through critical self-examination, and subsequent self-development; for it is only through self-improvement that all social improvement comes. We will strive in vain for success and happiness, in public and private life, unless each of us can continue to give some kind of affirmative answer to the pointed question that one of the Great Issues speakers addressed to us this year: "If you come knocking on the door of yourself, will you find anyone at home?"

It is that "twilight sleep of individuality" which has caused much of the hollowness and emptiness that we see within and around us today. The importance, the worth and dignity of the individual, free from the fictions of group prejudice, is what Dartmouth has instilled in us. It is that principle which has been contested by the avowed totalitarianisms whether black, brown, or red of the past two decades. As long as our educational institutions continue their search for truth, unswayed by the frantic voices of the hour, and based on the importance of the individual, they stand as one of the strongest bastions of democratic faith.

It cannot be too of ten repeated that the only valid test of an education is the person it has produced. There is more than casual import in the use of the word person. "The person in an individual," said Mark Van Doren, "is the man in him, the thing that politics respects; it is the source of language; it is the explanation of love. We praise persons for the virtues in them which they share with other men."

These college years have brought their moments of unhapp in ess, and failure, as well as this moment of the satisfaction of accomplishment. What we regret most however are not those failures, but the moments of in differentism, of boredom, that if allowed to become the pattern of the years ahead will turn the material benefits of wealth and success into ashes in the mouth. The power of an education comes in its daily application in the communities in which we live. One does not become familiar with ideals by precept or argument alone, but by active commitments. In a frightened and disillusioned age, nothing is so impressive and convincing as a living example. The supreme challenge the liberally-educated man faces today is to put hope back into human hearts.

It is said that an educated man should be able to hear the march of the ages. Let us keep our ears attuned to the footfalls of the persons around us too. Let it begin today with the first steps that we take as we join the unbroken procession of 183 Dartmouth graduating classes. "Though round the girdled earth" those footsteps lead, "show an affirming flame!" Let that dedication by each of us be our farewell to Dartmouth.

VALEDICTORIAN: John H. Sigler '53 of Indianapolis, president of the Undergraduate Council, Barrett Cup winner, and top man scholastically in his class, who spoke on behalf of the seniors.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

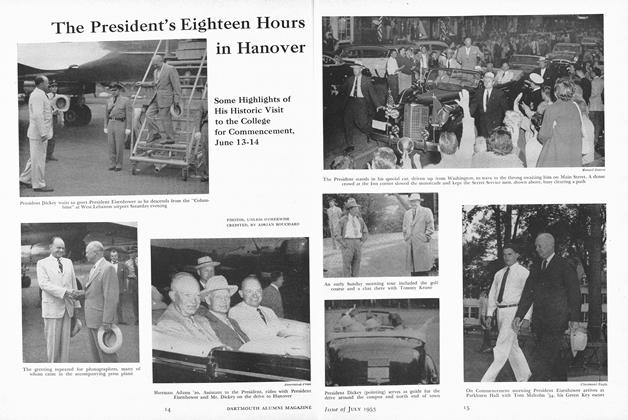

Cover StoryThe President's Eighteen Hours in Hanover

July 1953 By ADRIAN BOUCHARD -

Article

ArticleThe 1953 Commencement

July 1953 -

Article

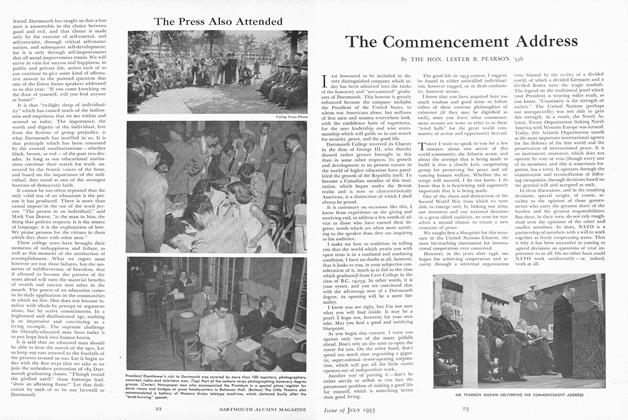

ArticleThe Commencement Address

July 1953 By THE HON. LESTER B. PEARSON '53h -

Class Notes

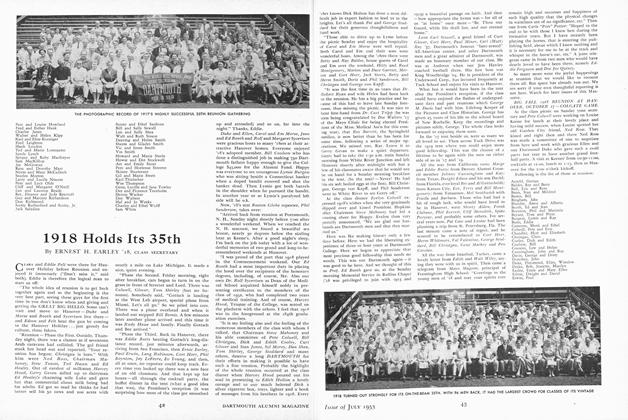

Class Notes1918 Holds Its 35th

July 1953 By ERNEST H. EARLEY '18, -

Class Notes

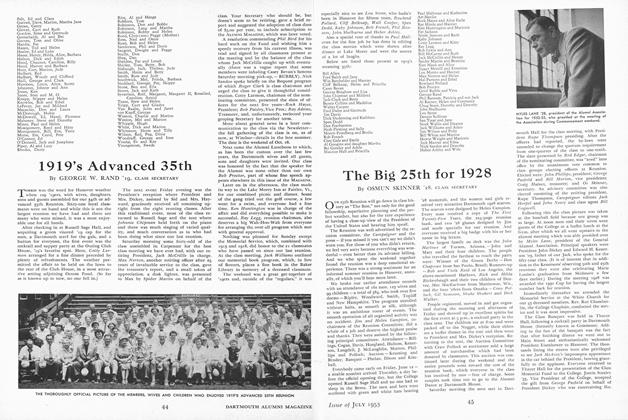

Class NotesThe Big 25th for 1928

July 1953 By OSMUN SKINNER '28, -

Class Notes

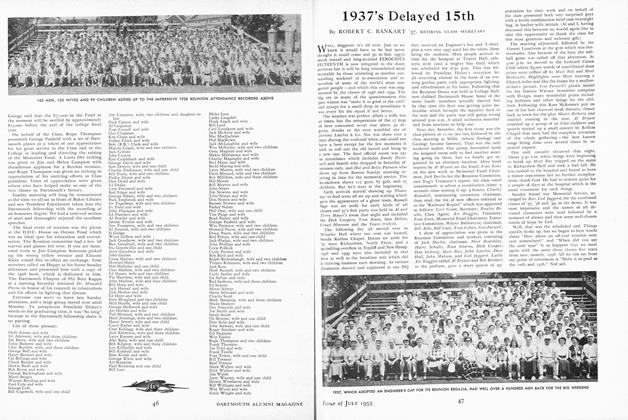

Class Notes1937's Delayed 15th

July 1953 By ROBERT C. BANKART '37