MY nine-year association with the Dartmouth athletic program, first as a participant and then as an observer, has led me to share former Sports Information Director Jack DeGange's opinion (June issue) that the development of the women's sports program is Seaver Peters' finest achievement as director of Dartmouth athletics. Yet without disparaging that remarkable progress, the simple truth is that vast disparities remain in the athletic opportunities available to Dartmouth's men and women. The same urgent effort that brought the women's program to its current level must be sustained, and perhaps heightened, if Dartmouth is ever going to offer its women an equal athletic program.

The discrimination against the women is most obvious in the disparity of opportunity in the athletic program. Women compete in 12 sports while men compete in 20. The women play fewer games than the men, and they are less likely to have subvarsity squads or assistant coaches. Even the head coaches are generally employed part-time or are required to coach more than one varsity sport.

The lack of subvarsity squads and the shorter schedule hamper the growth of women's sports by making it difficult for women to acquire the competitive experience that athletic success requires. The absence of full-time coaches who specialize in one sport deprive the women of the personal contact with their coaches that Dartmouth men enjoy.

The explanation for these inequities is that there are not enough women athletes to support an equal athletic program. It is argued that Dartmouth meets the needs of its women by providing teams in new sports whenever sufficient interest in a sport is demonstrated and by increasing its support of existing teams as their competence increases. '

Aside from the fact that the shortage of women athletes is partly the result of the enrollment ratio, the flaw in this argument is that it places the burden of improving the program on the women rather than on the College. Women who have interest in any sport other than the relatively few offered must convince the administration that there is enough interest in that sport to warrant institutional support. Dartmouth men, by way of contrast, step into one of the most varied athletic programs in the country.

Instead of waiting for the women to organize new teams, I suggest that Dartmouth take the initiative by establishing and supporting women's teams in sports in which other colleges are already competing, such as soccer, volleyball, and golf. This will help the women's program achieve parity sooner than it will under the current system. It is also time that the women's teams which have demonstrated their competence share facilities and support equally with the men.

A more subtle form of discrimination is the refusal of many people to accept women as serious athletes. The relatively low caliber of women's performances, compared with the achievements of men of the same age, and the physiological differences between men and women are cited as evidence that women will never approach the skill of men athletes. This opinion ignores the remarkable revolution which women's sports have experienced in recent years. Increasing numbers of women are competing in every sport in which men compete and they are eroding traditional ideas about the limits of feminine athletic ability and traditional ideas about the femininity of women athletes. The countless young women who are benefiting from an earlier start in sports along with better facilities and coaching seem destined to push these limits back even further when they reach their athletic peak. Although the transformation of women's sports is just underway, it already seems certain that current differences in male and female athletic performance will diminish considerably.

Those who insist that physical differences will prevent women from ever reaching absolute parity with men may be right, but they miss the point. Even if it is never as skilled, competition among women can be as exciting and dramatic as any competition among men. An analogy is provided by comparing intercollegiate and professional football. No one would suggest that an average Ivy League football player has. the strength, speed, or coordination of a professional player, but it is arguable that the college game is a more exciting sporting event. I have watched women's crews row with exquisite grace and I have watched women's volleyball teams battle for national supremacy, and the question of how any of them would fare against a men's team fades into insignificance. Their struggle to push themselves to the limit of their ability produced the same exhilaration that I always find in athletic competition.

A third source of discrimination is the admissions policy. The women's program draws its athletes from a female enrollment only a third as large as the male enrollment. This disparity is detrimental to existing women's teams because they contain fewer talented athletes than they would if equal access were adopted. The disparity also hampers the establishment of teams in other sports because it reduces the chances that there will be enough interested women to bear the burden of inducing in- stitutional support for a new team.

One argument against equal access is that any further decrease in the male enrollment would make it impossible for Dartmouth to maintain a competitive program in the Ivy League. Although the size of the enrollment is an important factor in the success of an athletic program, I doubt that the consequences of equal access are necessarily as dismal as is usually assumed. A firm commitment to the athletic program, in the form of a better athletic plant, more coaches, and perhaps better coordination with the admissions department, could compensate for the decrease in male enrollment. Even if equal access does make it impossible to maintain the current level of competition, it does not follow that Dartmouth would have to drop out of the Ivy League entirely. Dartmouth could continue to compete in the Ivy League in selected sports and compete against other New England institutions of similar enrollment in other sports.

The consequence of this discrimination is that it reduces the educational opportunities of Dartmouth women. My experiences as an athlete have led me to regard sport as an excellent instrument for teaching the values of fellowship,' persistence, and sportmanship, values that will shape the character of athletes' lives as much as anything substantive taught in the classroom. It is precisely this faith in the educational function of sport that leads me to conclude that Dartmouth can never offer its women an equal education as long as it denies them equal athletic opportunity.

Wayne Young, co-captain of the 1971 Ivy football champions,works for the Criminal Defense Division of the Legal Aid Societyof New York.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureScience and Technology Under Siege

September | October 1977 By Thomas Laaspere -

Feature

FeatureThirty-Eight Days Alone

September | October 1977 By Ned Roesler -

Feature

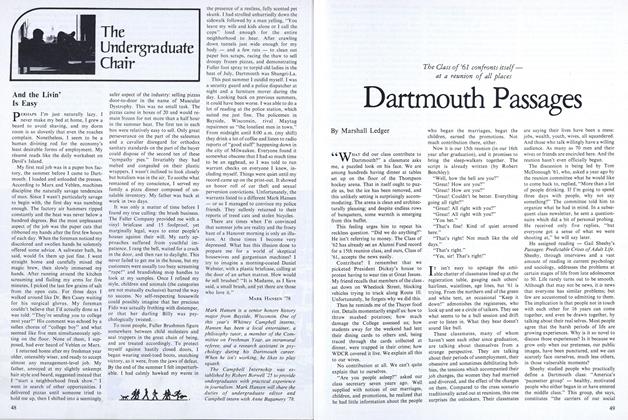

FeatureDartmouth Passages

September | October 1977 By Marshall Ledger -

Feature

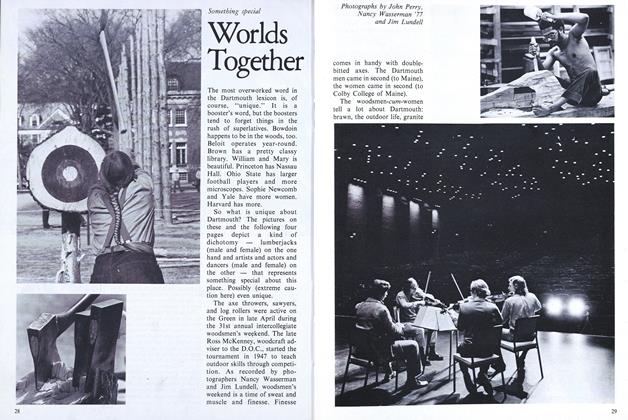

FeatureWorlds Together

September | October 1977 -

Article

ArticleFanciers

September | October 1977 By BRAD HILLS '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1927

September | October 1977 By ERWIN B. PADDOCK