Leslie A. Viereck '51 was a member of thefour-man party that successfully climbed Mt.McKinley in May and then during the descent suffered a tragic mishap that killed oneman and seriously injured another. Followingis his account of the experience as written toJohn Rand '38, executive director of the Dartmouth Outing Club. It is printed with thepermission of Viereck, who was serving withthe U.S. Army in Alaska at the time of theclimb and is now studying at the McGillKnob Lake Sub-Arctic Research Laboratory.

Up until the time of our fall the climb had run very smoothly although a little behind schedule. The route had proved much longer and more difficult than we had figured on from the aerial photos but through persistence and long days we had managed to get up over three difficult slopes and reach the summit.

We went in from Curry on April 17. It seemed early but proved to be the best time of year as we had good weather and lost only four days because of bad weather. We snowshoed in about 20 miles to the Ruth Glacier and then 20 miles up it to what was called the Great Basin. It was terrific country and most of it had not been entered since 1910, the date of the last expedition to try McKinley from the south. We received an air drop of food and equipment in the Great Basin and then relayed a double load about ten more miles up the glacier where we established base camp at 10,000 feet.

It was here that we encountered our first steep face of about 2,000 feet. From that point on we used crampons. This first slope wasn't too bad although it was steep. The slope was such that we could kick steps in most of it and only had to cut steps and use a fixed rope over a 300-foot section. It took three days to relay our packs up the slope and establish camp on the ridge above it.

From there we moved a short distance across a very narrow ridge and established Camp 2 in a plateau below the south buttress. The slope up onto the buttress was the most difficult one that we encountered. We camped eight days beneath the slope going up each day and cutting steps and returning at night. Here we encountered our. only bad weather and had to stay in the tent for three days. In all we cut over 1,000 steps (actual count - 1038) and used all our pitons and fixed rope.

The going on the buttress wasn't as easy as we had figured and it took us two days to make the five miles even though we had stopped relaying at this point. From the buttress we dropped down to 14,000 feet into the Traleika Cirque. Another bad slope and steep ridge brought us up to an extension of Karsten's Ridge. From this point we knew that we could descend the mountain by the conventional climbing route rather than having to retrace our steps. We figured that it would be safer to do this even though it meant going down over a route that we hadn't climbed. Woody had been over the route in 1947 so it wasn't completely strange to all of us.

We'established our high camp at 17,350 ft. and climbed to the summit and back the next day. Our route had brought us up so gradually that we had no altitude sickness at all and had no trouble reaching the top.

The next day was our tragic one. We started down the Harper Glacier to Karsten's Ridge early in the morning. By noon we were on the ridge and having no difficulty. The snow conditions got worse and worse. There was about a foot of very soft snow on a very uncertain surface. It was too hard to get an ice axe shaft belay but not good enough to put in pitons. We came to a very steep point in the ridge that was almost a cliff. We decided to go out on the slope and traverse out and back and thus bypass the steep part of the ridge. We were climbing one at a time with Argus leading, Woody next, then me and Thayer last. We were all out on the slope except Thayer. We all had pick belays but I didn't think that it was enough so I had the fixed rope passed to me. This was tied in above to a wicket that had been left by a previous climb and tested by us. I tied this rope around my ice axe for further safety. When Thayer slipped he started a snow avalanche. He got going so fast that my belay didn't even slow him down. He pulled us all off before we knew what had happened. We fell about 1,000 feet altogether - sometimes falling along the slope and other times falling free. It was a rather horrible experience, there was no way of stopping ourselves. I fought with my pack most of the way and finally got off. We were stopped in our fall by my falling into a crevasse on the slope while the rest went out over it.

Thayer was caught on the side of a vertical cliff and killed instantly, George was down below pretty much in a daze and with a badly-dislocated hip and quite badly banged up in his face. Woody was O.K. but had difficulty getting out of the rope as it was tight between Thayer and Argus and because he had lost his knife. I was out of sight of the rest of them and considered myself the only one left alive. I was in a daze and couldn't get my breath. This condition along with coughing up blood lasted for a couple of days and I presume was caused by severe bruising of the chest cavity - there were no broken ribs. Woody and I managed to level out a spot and find the big tent and three sleeping bags - all the packs except mine had burst open, mine was whole but I lost my sleeping bag as it was lashed on the outside of my pack. We dragged George down to the tent and got him on an air mattress and wrapped in a down quilt. I got in the sack also as my hands were frostbitten - I had lost my mittens - and I was in pretty poor shape to help much. Woody managed to gather up all the stuff that hadn't been buried under the snow. We managed to get most of the essential things including two air mattresses, two pair of snowshoes, both tents and some of all our food except tea and cheese. We were extremely lucky in saving three out of the four quart cans of gas that we had with us.

We stayed with Argus in this camp for six days. It was a hell of a place to be camped as we were still on a steep avalanche slope. We figured that we would just have to take a chance on the weather as we were in no condition to move Argus down the slope to the glacier and Argus was in no condition to be moved. We had codeine and morphine for George and used tip all our codeine but never had to use the morphine.

For the whole. week that we were there Woody and I tried to figure out just what had caused our fall but concluded that it was just a series of circumstances that just seemed to build up against us. We were climbing with heavy packs as we had to pack all our equipment including snowshoes to the 17,000-ft. level. As usual when accidents happen, it was getting on in the afternoon and we were tired as-we had come down all the way from 17,000 ft. and had gone over a difficult stretch of Karstens Ridge where there was 600 ft. of fixed rope left from other years. We were using pick belays with our ice axes as the under surface was too hard for a shaft belay. I think we all realize now the fallacy of depending on an uncertain belay. The wicket that we had the fixed rope to broke off or pulled out as the fixed rope was still tied to my ice axe when I found it in the snow where we stopped. We had tested it but perhaps not enough. The wicket was of good strong hickory and about 1 and ½ in. in diameter so it shouldn't have broken. Also we may have got a little careless in that we were only 200 yds. from being down to good safe going on the ridge. We had been on much steeper slopes and perhaps were a little overconfident. About all I can say about the accident is that it was one of those things that you have to expect in climbing but never really do. I consider myself lucky to be alive but I wish that we could all have been as lucky.

At the end of six days, three of which were clear, Woody and I decided that there was small chance of search planes even though we were a week overdue. Actually there were three private planes looking for us each day including one flown by Woody's wife but the mountain is so tremendous that they never saw us or we them during that time. At 04:00 Woody and I explored a route down to the glacier over the 2000 feet of slope. It was a hell of a steep avalanche slope and we didn't like it a bit. At one time we almost decided to dig a cave and leave George where he was. A lot of the slope had real deep snow all ready to go. We made a wide trough in this. In other places the snow had slid off the slope and we had to cut a groove for the litter that we made. We returned to the tent from the glacier about noon and wrapped George in two air mattresses, all the sleeping bags, and both tents. We wrapped him up in rope and then ran the climbing rope through all the loops of rope and then to Woody up front and me behind. It was lousy to have the responsibility of a helpless man but we had little choice. We managed to get him down O.K. but it took us until 10:30 that night. We kept a good belay on him at all times but we had some pretty hairy moments. Both Woody and I feel that getting him down to the glacier was more of an accomplishment than climbing the mountain.

The next morning Woody's wife flew right over the tent without seeing us. She was looking for tracks on the ridge and missed our tent as we were in the shade. We decided right then to start out rather than wait another day. By now George could sit up and cook and he wasn't in too much pain unless he moved. We had only a week's supply of food for one man and less gas so we figured that we couldn't wait out a rescue for much longer. Woody and I left at noon of that day with a couple of Logan biscuits and some chocolate. The glacier was in terrible shape - the warming of the northern climate coupled with rain up to 12,000 feet last summer and very little snow this winter made going extremely hazardous. This was the main thing that held up the rescue party later on. It took Woody and me about 12 hours to get down over the Great Serac and down to the smooth glacier. By then we were both nervous wrecks and shaking from too many close calls. About every ten steps we would go into a crevasse with one foot or another. We made McGonnagal Pass at about 03:30 the next morning and stopped for about three hours sleep. From there we headed down Cache Creek and into the tundra country. We hiked all the next day going slower and slower as the lack of food took effect. We hiked all the following night and crossed the McKinley River at about 06:00 the: next day and found a Park cabin with a little food. We stopped there for two-hours" sleep and then went on to Wonder Lake Ranger Station. We found much to our dismay that the Park road wasn't open yet for the summer. We then hiked down to a trapper's cabin where we hoped to get word out over a radio - his batteries turned out to be dead. Luckily they got the road open that very day and we were able to give the whole story to the Superintendent of the park, Grant Pearson, an old climber himself. He took over completely from feeding us to tearing in with us over the 100-mile road to headquarters where he could call the loth Air Rescue. Things really worked fast and we briefed the first of the rescue team at 04:00 the next morning and they were in on the glacier by 06:00. It was a wonderful feeling to know that the rescue was taken over by men far more capable than ourselves and that we could only be in the way if we tried to go back in with them.

As you know it took the rescue party 4½ days to get in to George, making it a week that he was alone. He had been very saving on gas and food and still had four days' supply of both. His hip was dislocated, not broken, and we are hoping that there will be no complications.

Well, that's the story in brief. I send it to you in the hope that maybe some of the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club men can figure out our mistakes and profit by them.

Just about the same as ever,

Les Viereck '51 on the summit of McKinley

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"The Working of the Religious Element"

October 1954 By GEORGE H. COLTON '35 -

Feature

Feature"The Individual and the College"

October 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

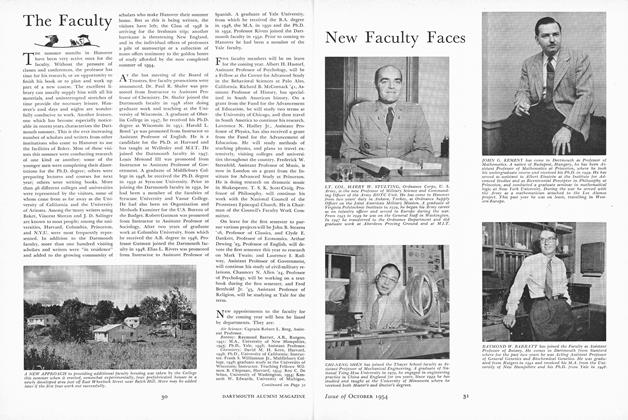

FeatureNew Faculty Faces

October 1954 -

Feature

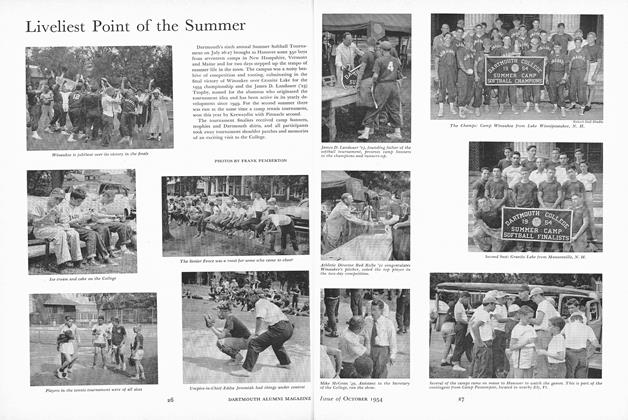

FeatureLiveliest Point of the Summer

October 1954 -

Feature

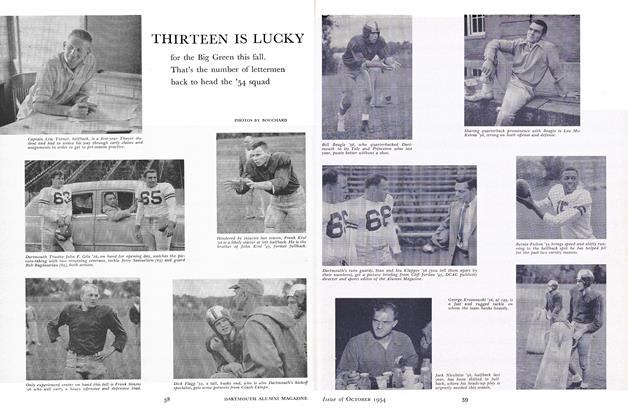

FeatureTHIRTEEN IS LUCKY

October 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1954 By ERNEST H. FARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE

Article

-

Article

ArticleCHARLES FREDERICK MATHEWSON, 1882

April, 1915 -

Article

ArticleScholarships Awarded

November 1932 -

Article

ArticleFourth Conference To Spur National Enrollment Work

October 1954 -

Article

ArticleHartshorn Medal Awarded

JUNE 1963 -

Article

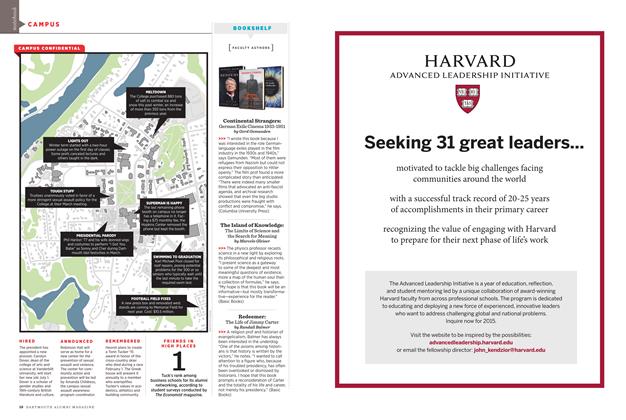

ArticleBOOKSHELF

MAY | JUNE 2014 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

May 1945 By G. W. Woodworth, H. L. Duncombe, Jr.