THERE lived centuries ago a philosopher named Plotinus who is said to have said, "If a man seeks the good life for anything outside itself, it is not the good life he is seeking." That is about all I know of Plotinus, but it was enough to help me out once when I needed just such a phrase.

The time was 1939 and I was returning to college after five years in business. That was before the GI Bill of Rights stepped up the age span of undergraduates, and my action was sufficiently "different" to set friends and relatives wondering. Why should a man in his twenties with a reasonably good job choose to become a sophomore again?

On the train to Hanover I gave the question some hard thought. My decision was made, but justification remained. I thumbed the catalog of courses for the second semester. The answer was there, I felt - but where, exactly?

To a college repatriate, a catalog of courses can have the charm that a seed catalog holds for the wintersick gardener. Here is fulfillment for the taking; a few preparations, a few right choices, and the garden of knowledge will bloom in your backyard.

Then reality comes through. There is only so much land, only so much time. Selection becomes all important. Which has the greatest yield? The greatest beauty? The greatest usefulness? I was pinned on this dilemma when Plotinus, dimly remembered, came to mind. I substituted "education" for "the good life" (it seemed to fit the immediate problem better) and decided to replant my little grown-over patch of land with the seedlings of the humanities. Literature, art, music, biography, history - didn't these studies best represent education for itself? And wasn't education for itself the end I was seeking? Onward with Plotinus.

Fifteen years later I can see that it really wasn't much of a problem at all. I chose the humanities, as abundantly as the College would permit, because I liked them and did well in them, reasons that have justified undergraduate course selection ever since the elective system introduced cafeteria style to higher education. Plotinus helped square my conscience, but there really wasn't any alternative.

Fifteen years later there's a much more important consideration to face: was the choice right as well as pleasant? Have the seedlings continued to grow? Do the humanities have a lasting value through the years?

That question has been wrestled with by experts. What puzzles me is the note of apology and defense that shows through so much of their discussions. They talk about the humanities as if they were accessories to education rather than the very stuff of education itself. Often, the most they can offer the student is a promise of some acquaintance with "culture" and a broadening of interests - features that might also be supplied by an all-expense trip to Europe and a knowledge of Canasta.

I don't recall ever hearing the physical or social sciences defended in this way. They seem so sure of their position in the vanguard of education, so confident of their importance that no defense is needed.

Undergraduates are quick to sense such differences and react to them. As a result, when a student turns to the humanities for more than just a sampling, he is apt to do so with an attitude of renunciation: "I know these courses will never help me earn a dollar but I'm going to take them anyway."

My own little quandary on returning to college is an example. I had to find refuge in pompous thoughts about "education for itself" (a ridiculous phrase, when you think about it) instead of simply indulging a healthy intuition that I'd be a better man if I knew more about what other men have thought and done.

But I am dodging my own questions and will try to get back to them. I say this apologetic attitude about the humanities puzzles me because my experience since leaving school has pretty well convinced me that the humanities - listen, parents of undergraduates! - are really the most practical of studies. They can and do "pay off." Properly presented and properly absorbed, they lead directly to the long years ahead. They have a thousand daily applications, offer a thousand aids to the business of living. No doubt they also contribute to culture and broadened interests, but the important point is that they are highly and delightfully useful.

Undergraduates, I'll tell you a secret. After you leave college you're not going to hear much about business with a capital B, or society with a capital S, or Human Relations as something you are likely to find in a factory or office. You will never come face to face with an Economic or a Social Stratum. There just ain't any such things.

You are going to be concerned, frequently and intensely, with individual men and women; with a succession of jobs and situations and problems; with individual achievement and failure, yours and others'. People and situations, with yourself at the center, these will fill your life.

Now the humanities can be very helpful in preparing you for these realities, and it's preparation you're paying for, isn't it? The humanities (let's try a definition) are human experience greatly expressed. That's all, but that's a good deal. They are the achievements of men who have encountered individual people and situations and have been able to tell about it in unforgettable language and line and color and music. Because they had genius, they could distill their experience into wisdom and mold it into artistic form. Because we are only ordinary folks, we need this guidance to understand our own encounters and deal with them graciously and effectively. Helping us do this is the business of the humanities; that is what they're all about. And nothing is more important in the 68 years more or less that the actuaries have allotted us.

If you will accept my premise that the humanities are human experience made articulate ("treasured up" was Milton's phrase) you will get a bonus, too, from your studies. You will find that part of the fun and knowledge comes from watching the artist at work, changing and developing and generally going through the same process that you always thought was happening just to you.

The great artists always talk about themselves, whether the medium is books or music or painting. Sometimes in meticulous detail, like Montaigne; sometimes by projecting their thoughts through others, like Shakespeare. Even when they are most elusive, like Leonardo, or most contradictory, like Beethoven, you can follow them about, looking for the secret that is the man. It's good practice because you will be doing just that, one way or another, the rest of your life. You want practical studies? Believe me, this is it!

In one of the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius (now there's a fellow to read if you think all philosophy is fuzzy) the soldier-emperor speaks of someone who is "deep dyed with justice." It's a good phrase to borrow in assessing the value of the humanities. These subjects become a shaping force in a man's life, I imagine, when they begin to color his thought and action deep through. To be "deep dyed" in learning must be quite different from being, say, knowledgeable or well-read or even a Phi Bete or a Ph.D. It takes a long while, a lifetime perhaps. But college can provide a good start.

A word of caution, though, based on errors I can see in my own backward glance. An enormous amount of litera- ture has been written "about" the hu- manities, and it's temptingly easy to ac- cept these digests and anthologies and surveys as legitimate substitutes for the real thing. They aren't. Approached in this way, the Classic becomes an academic "thing" rather than the work of a man. There is no direct communication and hence no lasting value. The "dyeing" process never really gets started.

Thoreau can be your guide here. Thoreau's chapter on Reading in Walden is one piece of "about" literature I would recommend. You can read it in fifteen minutes, then spend the rest of your life trying to meet its challenge.

The pleasant fact is that you needn't go off to the Walden woods to do so. The humanities can become a woven part of most any life you make for yourself, so much so that you will even forget that they were ever courses or studies. You will go back to them as you would visit a friend and will be a better accountant or lawyer or advertising man or wheat farmer because you have made something more of your personal lif'e than just marking time between chores.

There are compensations, as well as unpleasantness, to approaching middle age. Among them is a sort of weeding out of interests. Much that once seemed very important becomes trivial; much that was once only sensed, becomes real. Here, a bond with the humanities can stand by you resolutely. When you blow the dust off books you have carried with you since college and open them again for pleasure's sake, you will be glad that someone made you at least learn their titles and authors. You may even wish that you had been made to learn a good deal more about them when there was so much time to do so.

For by now you have some experience of your own to measure up with theirs; new meaning and delight comes through. You can skip the dull passages without fear of missing quiz questions and put the volume back when you choose, until some half-remembered phrase again leads you to it. Meanwhile, you have added one more bit of wisdom to your personal equipment and brought a touch of beauty into a life that may have too little of beauty in it. This continually renewed acquaintance with the humanities is among their greatest rewards.

And there is a further reward that we who look to the humanities for help can always hope for, at least. If we are among the favored who escape for long years the hazards of war, lung cancer, automobile accidents, cardiac deterioration and the communist state - we might, after eightyodd years or so, we just might even become educated men!

THE AUTHOR: Theodore Wachs Jr. '41 of North Haven, Connecticut, until recently was Director of Public Relations for the Connecticut Blue Cross. Following his graduation from Dartmouth with honors, he was for five years a Special Agent with the F.B.I., and then helped organize and operate the Tennessee Hospital Service Association before going to Connecticut in 1947. Originally a member of the Class of 1936, he withdrew from college in his sophomore year and after doing advertising and promotion work for Condé Nast and trade magazines returned to his studies in 1939. An honors student in English, he was a Senior Fellow, a Rufus Choate Scholar, and a member of Phi Beta Kappa, Alpha Delta Phi and Sphinx. The article printed here was not written with publication in mind but was an expression of "postscript thoughts" sent to Prof. Donald Bartlett '24 after Wachs and his former teacher had visited together in North Haven and had talked about the value of the humanities in post-college life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDOCTORS, ESKIMOS and DOGS

November 1954 By DR. ERWIN C. MILLER '20 -

Feature

FeatureThe Liberating Arts

November 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1954 By G.H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Article

ArticleA Roster of Dartmouth Alumni Clubs

November 1954 -

Article

ArticleFootball

November 1954 By CLIFF JORDAN '45

Features

-

Feature

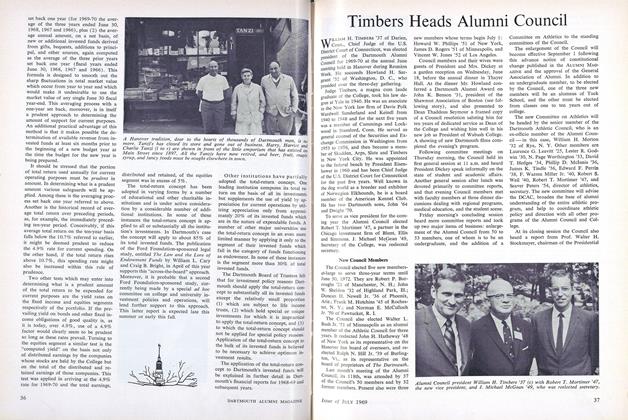

FeatureTimbers Heads Alumni Council

JULY 1969 -

Feature

FeatureIvy League bands: The beat goes on

OCTOBER 1972 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Doctor of Philosophy

December 1991 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn P. Collier '72, Th'77

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO PACK LIKE A PRO

Sept/Oct 2001 By NELSON ARMSTRONG '71 -

Feature

FeatureTeaching at a Communist University

JUNE 1971 By NOEL PERRIN