I HAVE always been fascinated by the Arctic ever since I was a boy in knee britches. I vividly remember attending some of the lectures given by Sir Wilfred Grenfell when he visited my boyhood community in northern New York State to tell about the work that the Grenfell Mission was doing among the deep-sea fishers living on the bleak arctic coast of Newfoundland and the Labrador. Sir Wilfred instilled in me the deep-seated desire to see the country where he did such a marvelous job among the natives, the Indians, and the Eskimos who otherwise would not have received any medical treatment whatever during their lives on the Coast. Since those early days I have read practically every book written by such men as Rasmussen, Peter Freuchen, Peary, Captain Bob Bartlett, Townsend, Stefansson, Grenfell, Commander Donald MacMillan, and works of many, many others who have spent so much of their lives in the cold, barren, wilderness areas of the Arctic.

A small fraction of my desire to see Newfoundland and the Labrador was realized just a few years ago when Paul Sample, Dartmouth's artist in residence, Sid Hayward, Robert Stoddard of Worcester, and I spent several weeks with native guides on a Newfoundland fishing boat, exploring and fishing the wilderness area of the northwest Newfoundland coast and the southern coast of Labrador. During the trip I had the opportunity to visit several of the Grenfell Nursing Stations and to examine and treat many people living in that remote area of the world. I then saw at first-hand the wonderful work that the people of the Grenfell Mission are doing and learned what great sacrifices they are making in such remote areas as Forteau, Flower Cove, Harrington and Mutton Bay.

Last fall I attended a Boston meeting of the New England Association of the International Grenfell Association, and during this meeting Dr. Charles Curtis, the successor to Sir Wilfred Grenfell as the Superintendent of the whole Grenfell Mission with headquarters at St. Anthony, Newfoundland, asked me if I would be interested, as a director of the Association, in making an inspection trip of the more northern areas served by the Mission in company with Dr. Anthony Paddon, the medical officer in charge of our North West River Grenfell Hospital. I immediately informed Dr. Curtis that if I could possibly get away from my medical practice in Worcester for a sufficient period of time, I would be very happy to join Dr. Paddon in his annual winter trip to the northern regions of Labrador.

Dr. Anthony Paddon was born on the Labrador coast where his father had been a Grenfell Mission doctor for many years, serving under Sir Wilfred Grenfell in the area around Hamilton Inlet, about 200 miles north of the Strait of Belle Isle.

"Tony" Paddon went to the Lenox School and Trinity College, and received his medical training at the Long Island Medical School in Brooklyn. After interning he returned to the Coast in charge of the 24-bed Grenfell Hospital at North West River where he has been serving the Indians, natives, and Eskimos of that area ever since. Tony had a "year out" a year ago and spent that period studying special diseases at the Mary Hitchcock Hospital in Hanover. He is a profoundly capable physician and a "Jack of all trades" in the North West River area. In his life in that community he not only has to have a knowledge of all fields of medicine, but he also must be a craftsman in carpentry, engineering, plumbing and building, and in repair work of a thousand different kinds.

After many days of careful preparation in the selection and assembling of arctic clothing, sleeping equipment, films, cameras, etc., I bade goodbye to my family and on February 28 flew from Boston by Northeast Airlines to Montreal. There I met Dr. Paddon, and after a 24-hour delay because of storms over the Labrador coast we flew by a Trans-Canada "Roundabout" DC-6 to Goose Bay, Labrador. It is a beautiful flight over the St. Lawrence valley with a route that takes one over the Saguenay River territory, the Laurentide Park area, Seven Islands, and that 200-mile strip of wilderness territory to the Goose Bay landing field.

From Goose Bay we travelled cross country in a "massaging" snowmobile, crossed the river to the hospital at North West River, and joined Sheila Paddon, and the Paddons' beautiful two-weeks-old "Elizabeth the First."

The Labrador was experiencing one of its worst winters in many years with terrific arctic storms, very low temperatures, tremendous snow fall and zero visibility almost daily because of these blizzards. Dog-team travel was exceedingly difficult and many teams were being marooned in wilderness areas because of twenty to thirty feet of snow.

I was delighted to spend several days with the Paddons in the North West River area because this gave me an unusual opportunity to see what a magnificent job the Mission was doing at its most northern hospital. I had the opportunity to visit the Yale school there and see the work that was done in the Craft Center and other branches of the Mission. I watched Nurse Jean Smith, Dental Officer Roderick McCrae, and Dr. Paddon examine and treat many Indian, Eskimo, and "liveyere" patients.

Tony and I examined and treated over too patients during our month in the northern Labrador area, and most of these patients were Eskimos.

During this period at the North West River area, I spent a couple of days visiting the Nascopie Indian families in their tents at the little Indian Village across the river from the hospital. This last nomad tribe of Indians on the North American Continent come out from the interior of Labrador each year to pitch their tents and spend part of the winter months where their children can attend the Grenfell Mission school at North West River and where they can receive spiritual guidance from the Oblate Mission under their friendly adviser, Father Pierson.

One of the most interesting cases we saw while at North West River was a young Nascopie Indian girl with abdominal symptoms who at operation turned out to have an appendicial abscess caused by swallowing raw porcupine meat in which were imbedded several fairly large porcupine quills.

DR. PADDON finally caught up with his medical work at the North West River hospital and he, Nurse Smith, and I spent many hours arranging and packing the medical equipment, drugs, records, dehydrated food, and other supplies for our trip north. We were to travel by bush pilot's plane and dog team to Hebron, which is the most northern Eskimo village on the Labrador coast, and back again to North West River through some of the most gruelling and exciting experiences one could possibly have in that cold, barren, and unmapped wilderness area.

I was out fishing with some of the Nascopie Indians during the latter part of my stay at North West River and was unfortunate enough to fall through the ice and had to travel several miles before finding a sheltered area in which to treat my partially frozen right foot. But this turned out to be a very minor experience compared with the hazards that awaited us on our trip nearly 600 miles north of the Goose Bay area.

The flight north was to be made in a "Norseman" plane piloted by Tom Watt, a veteran Canadian and American bomber pilot who was shot down several times over the German lines and who was one of the heroes in D. B. Williams' exciting novel of the war called The WoodenHorse, telling of his and Tom Watt's tunnelling out of the famous German prison, Stalag 7, during the war. I could not have had a better team for this part of our journey as I have tremendous faith in the air-worthiness of a "Norseman" and have flown many miles over wilderness and bush country in one. Tom Watt is one of the best pilots I have ever flown with and I salute him for the wonderful judgment he showed in flying this schedule under terrific weather conditions and without adequate weather information or aerial maps at any time during our journey.

Monday, March 8 was a clear cold day in North West River. Tony and I awakened early, took the last hot bath we were to experience in nearly three weeks (we hardly undressed for two weeks) and loaded all our equipment on the plane, plus four Eskimo and Nascopie patients who had been receiving treatment at the North West River hospital.

The take-off from the ice in our skiequipped plane was neatly managed and we were soon flying with Tom at an altitude of approximately 3,000 feet over the rugged lake-studded terrain toward Davis Inlet where we were going to land two of our recently hospitalized Nascopie Indian patients.

When we were between Hopedale and Davis Inlet we ran into foul weather with extremely high winds and nearly zero visibility because of an arctic blizzard. Tom had to make an emergency landing on an inland lake in order to "sit out" the storm before continuing our flight north. I tried to amuse our patients during this trip by drawing sketches of them and pointing out unusual geographic formations we were flying over. They were exceedingly unemotional and did not seem to fear any part of the flight.

We stopped at Davis Inlet for only a brief time, and then flew on to Nain, which is the Eskimo metropolis of northern Labrador, with a population of some 300 Eskimos. We spent five days at Nain where we lived in the Moravian Mission home with the Reverend and Mrs. F. W. Peacock, missionaries for that area of Labrador. Bill Peacock has made a study of Eskimo life and has published a very fine treatise on this subject entitled "Some Psychological Aspects of the Impact of the White Man upon the Labrador Eskimo." Tony Paddon examined and treated many Eskimo patients at Nain, and I had an opportunity to talk to this delightful group of people and study many phases of Eskimo life. I also had an opportunity to have some of the Eskimo women make some fur clothing to be used during our trip to Nutak and Hebron where warm clothing was certainly a necessity, especially during our dogteam trips between the little Eskimo villages of this more northern part of the Laborador coast. It was.extremely interesting to watch these Eskimos cut and sew my seal skin boots, seal skin mushing mittens, and other fur articles. They softened the seal skin by chewing it and then sewed the seams with sinew and square needles. Their workmanship was beautiful and the boots they made were absolutely waterproof.

Commander David Nutt, Larry Coachman, and Jack Tangerman, the three Arctic specialists at Dartmouth College, flew into Nain to re-occupy oceanographic stations and continue their studies of the coastal waters of northern Labrador which they had started the year before, During our stay at Nain we organized the first "Dartmouth Club of the Labrador" and broadcast several times over Bill Peacock's station of 3420 kilocycles to the Eskimos of that area. The Blue Dolphin group was a great radio team and their shows were much appreciated.

The Moravians are the spiritual advisers for the Eskimos and have coastal Missions in the little villages from Makkovik north. Practically all the Eskimos in this northern area have been Christianized and seem to be deeply interested in religious teachings. I welcomed the opportunity to become acquainted with the Peacocks while at Nain and attended several Moravian Mission services given entirelyin the Eskimo language. The Eskimos of this area are a splend'd group of people, very friendly, courteous, intelligent, honest, and sincere.

Weather conditions again turned exceedingly vile when we wanted to fly from Nain to Nutak and Hebron with some of our Eskimo patients. Our first flight from Nain to Nutak brought us to within fifteen miles of that little Eskimo village when we encountered an arctic blizzard. We tried to fly around it and under it to make a landing but finally had to give up the effort because of the hazards of "blind flying" in the Kiglapait Mountain area. Reluctantly we returned to Nain that afternoon after having spent several hours in the air. There was only a quart of petrol in our tanks when we landed on the harbor ice.

We tried again the following day to make Nutak and again ran into foul weather, but this time we succeeded in flying to within two miles of Nutak before being compelled to retrace our flight south. The Eskimos in Nutak could hear our plane flying over at low altitude but could not see us even though we were less than a thousand feet above them. Tom Watt would not hazard a blind landing on the unknown ice and snow conditions of the Nutak Harbor area, and so we again flew back to the Mission at Nain. On the third day, and our third try, the "Norseman" made it, and we landed near Max Budgell's Newfoundland Government Commissary in this little Eskimo community in the Okak area.

We remained at Nutak long enough to land our Eskimo patients and deliver a few messages and then continued the flight north to Hebron. Hebron is the most northern Eskimo settlement on the coast with about 200 Eskimos and four white people. Dr. Paddon and I stayed with the Rev. Fred Crubb in the 160-foot-long Mission House built in 1881 of lumber brought from the Black Forest of Germany. The Grubbs are the Moravian missionaries in this isolated Eskimo community and have their three young children with them.

Tony and I were very busy with medical problems at Hebron and we "earmarked" several serious cases for future transfer to some of the Grenfell Hospitals where expert surgical treatment could be given.

Hebron and Nutak had both had very poor sealing years. This created real hardship, as life depends so much on the seal in Eskimo country, and because of the scarcity we could not obtain any food for our dogs.

Mrs. Miller had given me some rubber balloons and small plastic toys to take with me and the Eskimo children of Nutak and Hebron had a wonderful time trying to balance the balloons on their no es, heads and toes. It was the first time they had seen toys of this kind.

DR. PADDON and I spent three days on rried.'cal work at Hebron before we started our eventful dog-team journey south. We each had two Eskimo dog-team drivers who could not speak any English, two 18-foot komatiks, one 14-dog team, and one io-dog team. We also took along five puppies which were on this trip as part of an "internship" for future dog teams. Our first day out was a beautiful, sunny arctic day which permitted me to take many pictures of the terrain, ice conditions, and our dogs in action. The weather had been so cold during much of our stay in northern Labrador that all my cameras had frozen except one. We found that we could not keep our cameras where it was warm and therefore kept them outof-doors and out of reach of the dogs at all times. Warming the cameras would frost the lenses and internal mechanism which interfered seriously with the speed of the shutters. The factor of light conditions in that northern area was also a problem, but because of expert advice given me by many photographers of arctic expeditions, I was lucky in obtaining quite satisfactory colored motion pictures and still transparencies of our journey.

We were fortunate to cover over forty miles on the sea ice our first day out from Hebron, and stopped that night at a little seal hunter's cabin at a place called Green Cove, where we slept on the floor under a canopy of caribou skins, white fox fur, arctic hare pelts and polar bear skins, with pieces of seal and bear meat hanging above us.

By mid-afternoon of our second day we noticed a violent storm approaching, and within less than an hour, the fury of a tremendous arctic blizzard was upon us. We were hardly able to see our dogs from the komatik and our drivers immediately started for shore to try and find a suitable place to make a snow house, but this was impossible because of the high winds and inability to find proper packed snow conditions for snow house construction. Conditions

were getting worse every minute but we finally found an old abandoned seal hunter's shack which was to be our retreat during the next four days of physical hardship. We had no adequate heat to warm the shack, the cold nights were sleepless, and the days seemed unending. The shack was almost completely covered by snow when we finally emerged. As our four Eskimo drivers could not speak any English, the six of us sat around these days more or less in a huddle trying to survive the elements. Tony had an American medical journal which he learned by heart, and I had the opportunity to reread the New Testament, which I carried on this trip, almost three times from cover to cover. One of our Eskimo dog-team drivers was the leading ivory carver of the northern coast and he spent most of his time carving dogs, walruses, seals, kyacks, dog teams and people out of pieces of wood which he tore from the floor and sides of our shack.

Fuel for heating gave out, the dogs did not have any food, and we, ourselves finally ran out of adequate rations. One of the Eskimo dog-team drivers thought he knew where a "cache" was located and after spending a long time in the blizzard, he finally returned dragging a frozen baby seal which apparently had been killed the year before, and which was eaten raw during the rest of our stay at Shark's Gut.

The hungry dogs were vicious and every time we had to venture out of the hut for physiological reasons, we were immediately surrounded by all 29 dogs. So we found it advisable at all times to go out into the blizzard in pairs for protection from attack by these hungry beasts. I ventured out alone one night and was immediately attacked by twenty of the dogs and was fortunate to be rescued by one of the dog-team drivers who got me back into the shack by clubbing the dogs away from me.

The northern Labrador sled dog is a vicious creature, being part Siberian husky and part wolf. In fact, the Eskimos breed the dogs with the wolves to keep up the wolf strain which gives the dog considerably more stamina. During the whole month spent in northern Labrador, I did not see a single sled dog that was made a pet. Many people are killed by the dogs every winter by being "jumped" by them, either while out on their dog-team trips or in their villages. There are more dogs than people, and when there is insufficient food, conditions sometimes reach a very serious state.

While we were holed up at Shark's Gut, Dave Nutt and the other members of the Blue Dolphin group were having a much worse time with the arctic storm than we were experiencing. Their group was marooned high in the Kiglapaits during their dog-team trip from Nain north and at the height of the storm was unable to keep a snow house intact.

The storm finally abated sufficiently to permit us to continue our journey south, but travelling was painfully slow and difficult because of the tremendous depth of the snow and the fact that our dogs had been unfed for so many days.

During the rest of the run south I lost my sun glasses one day and spent several hours without them riding and running beside my komatik. That night my eyes began to burn and pain violently and I learned how disagreeable even a minor attack of snow blindness could be. The tre- mendous glare of a clear arctic day is one of the hazards one must be particularly careful about.

We finally reached Nutak and welcomed the protection from the cold, some hot foods and liquids, and someone besides Tony and myself to talk to. But, the sled dogs did not fare so well; even here seal meat could not be obtained for them because of the poor hunting season of the previous fall.

It was interesting to watch the bartering between the Eskimos and the Newfoundland Commissary here at Nutak. The Eskimos brought in many kinds of furs and traded them over the counter for the variety of "white man's goods" they desired. Currency did not seem to be of much value in this area of the world.

Tony and I had intended to continue our dog-team trip south to Nain but several factors prevented our doing this. A team of ten dogs and a komatik which I was to use for this trip from Nutak south was lost at sea on an ice pan while out sealing and could not be replaced, and so because of the loss of my dog team and because of the severe storms we were advised by the Eskimos not to attempt a Nutak-to-Nain run, which required a climb over the Kiglapait Mountains. We therefore waited at Nutak until Tom Watt could fly in and take us back to Nain, and eventually to the North West River hospital and Tony's home.

On the flight south we ran into several severe arctic storms. When we flew over the ice area just north of the Kiglapaits we looked down at Dave Nutt and his teams, mushing their way foot by foot on their own trip north, and blessed our decision not to try the run south by ourselves.

MY expedition with Tony into the Nascopie Indian and Eskimo country was a tremendously thrilling, exciting, and interesting one, and I believe that we accomplished our mission in every respect. We had treated over 200 Eskimo and Indian patients and had seen practically every common and rare pathological condition likely to exist among these people of the far north. We saw several cases of the rare "seal finger" pathology; many unusual dermatological lesions, peculiar to arctic areas; we removed many foreign bodies such as square needles from the hands and wrists of Eskimo women; Tony pulled at least a pint of teeth; and I believe that we saw just about every type of tubercular lesion known to medical science.

I feel profoundly humble when I think of the intense hardships that the people of the Grenfell and Moravian Missions are enduring every day on the Coast, and what hazards they encounter during their service to the people of Newfoundland and the Labrador. Don't think for a moment that the Indians, Eskimos, and "live.yeres" of the Labrador and northern Newfoundland don't need the services of the Grenfell Mission, now, just as much as they did in Sir Wilfred Grenfell's time. ] salute the wonderful nurses, doctors, and workers in every field of endeavor in the Mission, whether at Harrington, Forteau, Cartwright, Flower Cove, St. Mary's, St. Anthony, or any one of the other hospitals and nursing stations "on the Coast."

Aksunai.

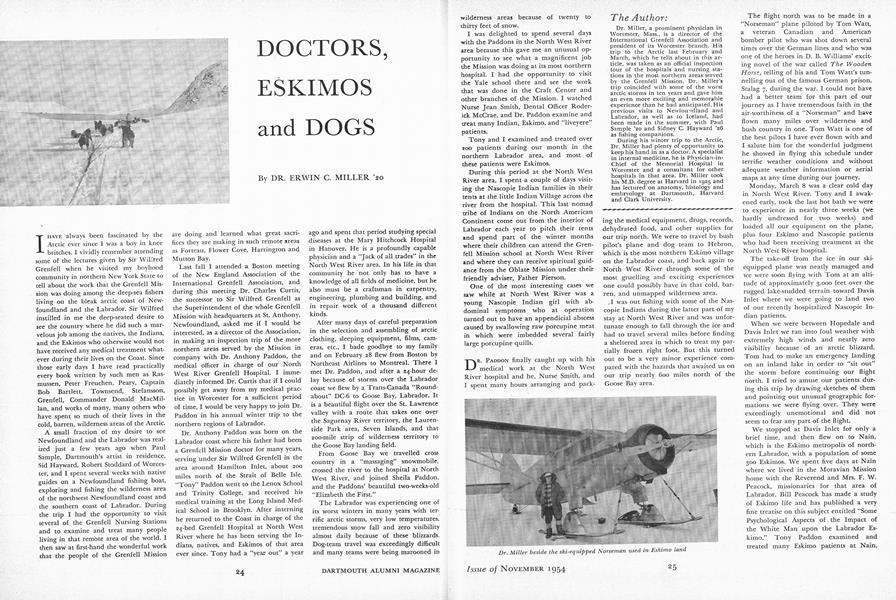

Dr. Miller beside the ski-equipped Norseman used in Eskimo land

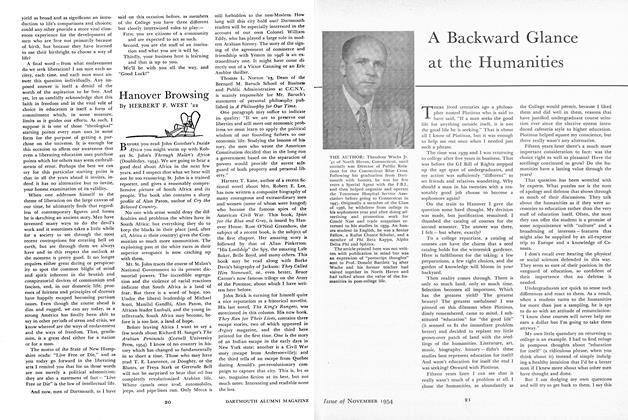

The party's four Eskimo dog-team drivers from Hebron. The second from the left litisthe reputation of being the foremost ivory carver on the northern Labrador coast.

Dr. Miller towers over the igloo built in theNutak area, but it slept six very comfortably.

The Author: Dr. Miller, a prominent physician in Worcester, Mass., is a director of the International Grenfell Association and president of its Worcester branch. His trip to the Arctic last February and March, which he tells about in this article, was taken as an official inspection tour of the hospitals and nursing stations in the most northern areas served by the Grenfell Mission. Dr. Miller's trip coincided with some of the worst arctic storms in ten years and gave him an even more exciting and memorable experience than he had anticipated. His previous visits to Newloundland and Labrador, as well as to Iceland, had been made in the summer, with Paul Sample '20 and Sidney C. Hayward '26 as fishing companions. During his winter trip to the Arctic, Dr. Miller had plenty of opportunity to keep his hand in as a doctor. A specialist in internal medicine, he is Physician-in-Chief of the Memorial Hospital in Worcester and a consultant for other hospitals in that area. Dr. Miller took his M.D. degree at Harvard in 1925 and has lectured on anatomy, histology and embryology at Dartmouth, Harvard and Clark University.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Liberating Arts

November 1954 -

Feature

FeatureA Backward Glance at the Humanities

November 1954 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1954 By G.H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Article

ArticleA Roster of Dartmouth Alumni Clubs

November 1954 -

Article

ArticleFootball

November 1954 By CLIFF JORDAN '45

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1969 -

Cover Story

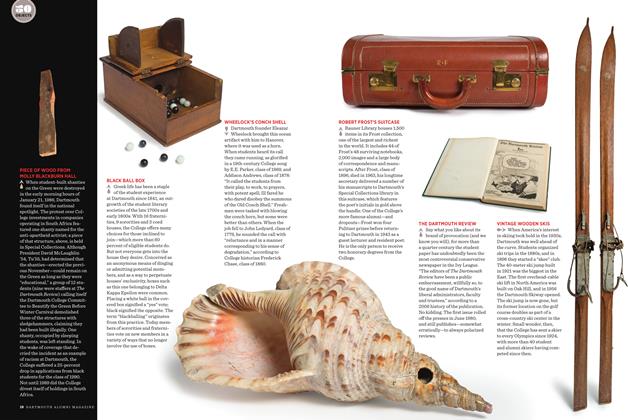

Cover StoryPIECE OF WOOD FROM MOLLY BLACKBURN HALL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureThat Spring in Jersey City

NOVEMBER 1971 By BRUCE ALAN KIMBALL '73 -

Feature

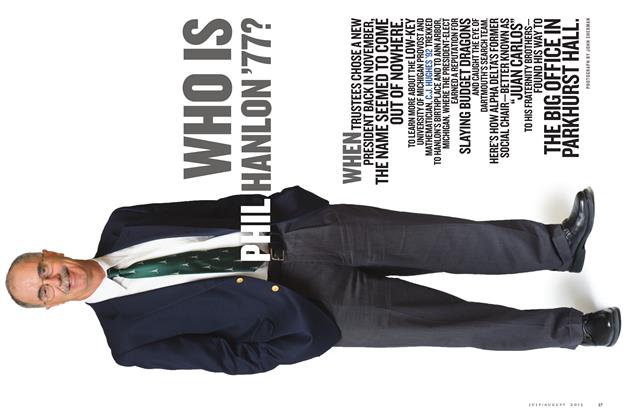

FeatureWho Is Phil Hanlon ’77?

July/Aug 2013 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Cover Story

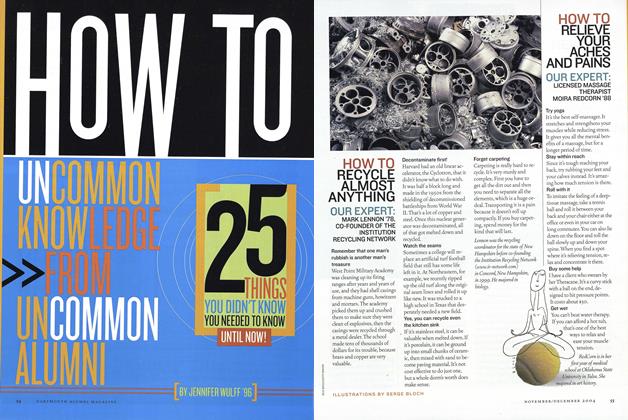

Cover StoryUncommon Knowledge From Uncommon Alumni

Nov/Dec 2004 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WIN CUSTOMERS WITH UNPRECEDENTED SERVICE

Jan/Feb 2009 By SCOTT MITCHELL '93