Ultimate and Timeless Issues for Man

I PROPOSE to plunge in medias res and try to indicate to you, first, two things of the relation of what I am going to talk about to the general intentions and the general structure of this extraordinary enterprise of the Great Issues Course. I hope before the lecture is concluded to have you see in what sense - and I mean this quite seriously - you are not, as some of you imagine, leaving the great and paramount and urgent issues of politics and economics and international relations and coming to the relatively trivial issues, as they must seem to you, the relatively precious or over-exquisite refinements of argument that may occur with respect to esthetic enjoyment in the creative arts. I am going to try, if I can, to make you see — or help you see - what I more than suspect perhaps some of you already do see, that in this final section of this enterprise you are really dealing with the great issues in the sense of the ultimate, the paramount, and the timeless issues with respect to the values of human experience and of human existence.

Now let me make one thing clear at the outset: that the great issues are not necessarily the most topically urgent issues. We are bedeviled by contemporaneity. We are bedeviled by the pressure of certain immediate urgencies, by the threats to freedom which are so intense and so menacing that we concentrate upon the threats to freedom at the expense of forgetting to consider what freedom is; which, when we do consider it, I think you will find leads us directly to matters that are commonly called esthetic, artistic and creative. We are so bemused and bedeviled by threats to established and traditional values in the western world, and by the quenching of the genesis of new values, that we again cease to occupy ourselves with some attention to what values ultimately are.

Within the past fortnight we've been bemused and bedeviled by the hydrogen bomb in the world and by demagogues, the chief of whom I shall not even mention by name. I'll leave you to guess. We're bedeviled by other things that are less recent and immediate. We've been bedeviled since the middle of the igth century — as John Stuart Mill, perhaps, was the first to make clear - by the paradox of the fact that the very conditions which are necessary to individuality and freedom in the modern world become so complex, so involved, so regimental an apparatus, that the very machinery which is needed socially to insure freedom turns out to be, perhaps, and dangerously, the instrument for its suppression. And, still continuing the sources of our bedevilment, we face the fact that the very first theme you were discussing in this course, mass communication, presents a paradox that has come to preoccupy us.

Early in the 19th century in England it was optimistically believed that the printing press and educational clubs of working men would transform society. Trust to the printed word and the world would be transformed! We've discovered the sinister fact since that the printed word can spread contagion, misinformation and poison. And now the heard word, and the televised word, and the televised picture, all of these instruments of communication can defeat the very process of education which, ideally, they may be expected to serve.

And still one more point on what I've called our bedevilment. There are at least three types of anxiety - and remember that the word anxiety has itself become almost a battle cry of a philosophy widely current in Europe and South America, particularly - existentialism. There are various kinds of anxiety, those private anxieties which have become popularly familiar in the popular cliches about psychiatry and psychoanalysis, a kind of uneasiness about ourselves which used to be called 'original sin' and is now, in a new jargon, called 'an inferiority complex,' the uneasiness that our most generous and dedicated ideals have their roots in childhood guilts, in carnal impulses, from which we have tried to hide ourselves, and the over-arching public anxieties of which the hydrogen bomb is simply the melodramatic climax; the paradox of a race which has achieved a skill so exquisitely comprehensive and allpowerful that it has the power now, and the danger, of destroying itself. And, finally, what may seem to you an odd term, what one may call 'cosmic anxiety,' the old traditional formulas, even for those with traditional pieties, do not operate. Theology and religion need to be recast. There is an uneasiness about whether the universe adds up to anything, to any meaning, or to any significance.

When you add up all these anxieties and all these pressing threats of external enemies and internal moral civil war, it is no wonder, I suggest, that in a more serious and fundamental sense the great issues are beclouded. And what do I mean, for I'm obviously using the word in a special sense, perhaps with a special ax to grind - if it isn't too great a contradiction in terms, a 'humanistic' ax? The great issues are something subtler, more delicate, more ultimate than immediate ones or the ones that have a fixed contemporary date upon them. If freedom is threatened, I repeat, what is freedom? If values are menaced, what values and what, ultimately, is value? You've had a succession of visiting lecturers in this course who have dealt with the most immediate and urgent issues: the tensions in international relations, the menace to freedom and the very machinery of our society, the threats involved in the very instruments of mass communication, which may, in the hands of demagogues, destroy democracy and freedom. All these you have been discussing, thinking about, reading about, and it may seem a very long way from those issues, questions of politics and economics and international relations, to the questions I'm going to be concerned with tonight, questions that involve what we commonly call 'the esthetic experience' and questions involving what we commonly call 'the creative process.'

WHAT is the connection between the issues which you have been concerned with up to now in this course and the issues, if they can be called issues, that I'm going to be concerned with tonight? You've all heard of controversies in art criticism; you've all perhaps heard the legends which happen to be true that occasionally in Paris feeling grows so high on some esthetic question that there is virtually civil war at the Opera or in the Comèdie Francaise. People leave in high dudgeon if they think the wrong actor has been chosen to play in a Molière play. There are excited arguments for weeks in the newspapers about whether the new decor of "Britannicus" is proper or appropriate or not. And when an American visitor reads about those things in the French press, he perhaps says to himself, "The French are notoriously excitable; these are perhaps very trivial matters; the way in which the verses of Racine are recited is not really world-shaking in a world in which the atomic bomb threatens all of us. Whether there is a change in the mise en scene of a Moliere play is hardly of the first importance."

In 1911, I believe it was, even in this country, there was held, what now seems rather old-hat and familiar, the famous Armory Exhibition at the old armory in New York of French impressionist and post-impressionist painting. And the dean of the newspaper art critics in New York at the time, Royal Cortissoz, announced with magisterial firmness that it was not a question of these being bad paintings, they were simply not painting at all. This included a Manet, a Degas, a Monet, which have become almost as familiar as "The Angels' Serenade" or the "Second Piano Concerto" of Rachmaninoff. There was violent argument about these things, just as there is violent argument pro and con about certain poets and novelists today, or certain abstractionist painters.

In that sense there are issues within the arts but that is not what I mean by the great issues as they come to focus in the arts and at all times and in all generations. What I should like to impress upon you this evening is not that there are violent controversies in esthetic circles so that perhaps you and your roommate may virtually have a civil war, he vulgarly preferring "The Pathétique Symphony" and you high-mindedly preferring a pure Bach fugue unaccompanied on the violin. I do not mean by the great issues as they come to focus in the arts simply esthetic differences. I mean something far more important and far more basic. The fact is that from the beginning of philosophical reflection on the subject of morality and of art, philosophers, even those who had precious little direct interest in the arts, have recognized that the great issues, the paramount concerns of humanity, come to evidence, come to fruition, and come to focus in the fine arts.

What do I mean by that? I mean simply this: ultimately, any moralist or any philosopher has to try to come to grips with what he regards as basically valuable or ultimately or intrinsically good. Remember that the apparatus of social life and economic life that you have been discussing and studying through this whole year remains instrumental, remains apparatus.

There's a story that William James used to like to tell of an old lady who was asked what holds up the earth, and she said quite firmly, "A rock."

And the ruthless questioner said, "What holds up the rock?"

She said quite firmly, "Another rock."

And the ruthless questioner, with no piety toward age, said, "What holds up that rock?"

She said, "Another rock."

He said "Madame, what holds up that rock.?". and she looked at him abd said, "Young man, it's rocks all the way down."

That is what in philosophy is more formally called 'infinite regress,' There comes a point at which, if we are to have any resoluteness or clarity upon what we regard as ultimate, we must, so to speak, say, "Here is where we stand."

And what has all this to do with the arts? It has to do with the subject matter of this part of the course, the esthetic and creative elements in any culture.

Suppose, for the moment, we use the term esthetic to identify that aspect of enjoyment and appreciation of contemplation and beholding, of aspects of art or nature which are delighted in for their own sakes. Suppose for the moment we use a term often very grandiosely used, 'beauty' or 'the beautiful,' as a summary name for what it is that is esthetically enjoyed. Ultimately, the arts illustrate what even moralists not concerned with the arts recognize, what even theologians recognize, for is not the attitude and bliss and salvation supposed traditionally to be a timeless and eternal beholding of God himself? Is not bliss a continued ecstasy of beholding and do not our experiences in the arts, where we have any responsiveness to them at all, a response to a poem, a response to music, a response to a play, or to a picture, are they not momentary instances, so to speak, truncated sections of eternity where we escape for the time being from time, where we escape for the time being from the pressure of practical necessities or biological urgencies and light in an act of vision on something for its own sweet and beautiful sake? Just as in religion even those who believe in God often feel the necessity of finding a formula or a demonstration of his existence, even those susceptible to and swayed by beautiful things feel the necessity of defining the grounds of judgment of what they enjoy, and a great deal of this section of your course will, of necessity, be concerned with an attempt to define the grounds of judgment of taste. The fact is, we are not content to say, "I like this." We convert the proposition "I like this" into "This is beautiful" and we try to find grounds for our judgment. But, whatever the grounds or difficulties of judging esthetic enjoyment may be, the fact is that the arts as enjoyed are experiences of values, intrinsic, and for themselves, and philosophers, as I was saying just a few moments ago, have all been aware of this, even philosophers, I repeat, with small intrinsic sensibility to the arts.

William James, again, in one of his letters quotes a German philosopher who wrote to him and said, "It's very curious about my brother. He loves beauty in the abstract but he cannot bear to look at a picture, to listen to music, or to read poetry. But he loves beauty, nonetheless."

There are philosophers who have not loved beautiful things, but have recognized the enormous power that what we call the arts have over human imagination and, therefore, over human conduct. As a matter of fact, this is a tradition philosophically from Plato down - Plato, himself a poet in essence, extraordinarily sensitive to the arts but, nonetheless, a founder of that tradition which in a sense flatters the arts and the artists by being extremely critical, suspicious, and censorious of the arts. And on what grounds have philosophers paid tribute to the arts by being critical of them?

ROUGHLY speaking, I should say there are three general critiques of the kind of seduction and power that the arts have.

The first is a moral suspicion of the arts that Plato was the first to enunciate historically, that the arts are distracting and corrupting by being sensuous, that they are addressed to an excitement and an exploitation of the senses and are, therefore, a diversion and a distraction from the serious responsibilities of reason in the soul and of order in the state.

And the second critique of the arts that runs right through moral criticism from Plato to Tolstoy and his little book Whatis Art? — an extremely powerful little book - is that the arts are, and you will pardon the expression, subversive. The arts are subversive and corruptive. Every work of art that has any claim to its own signature and its own uniqueness is obviously a small revolution. It's a revolution in a way of looking at things; it's a revolution in a way of speech; it's a revolution in ways of feeling.

You can find illustration throughout history of the truth of the moralistic suspicion of the artist, the suspicion that the artist is a kind of diversionist or distractor. It's a suspicion that has come not only from esthetics and puritans, but, what one may call the most serious charge on this ground of subversion, from practical people, from busy, pioneering, active men. In this country in the 19th century and to this day, as a matter of fact, there is still in certain active industrial quarters a faint suspicion that the arts are by nature decadent, destructive, and corrupting, to a practical civilization. It comes as nothing less than a tragedy in certain quarters, possibly in the families of some of you, if a son announces that he intends to be a poet or an actor. It's hard to know which the family regards as worse, often; they're both disreputable professions. When you could be building bigger and better motor cars or building bigger and better investment firms, to be, in Walter Pater's phrase, "concerned with the discernment of a tone on the hills a little lovelier than the rest" seems, relatively, trivial....

And the third charge is one made by what I am going to call the philistines, a term Matthew Arnold used to describe a sort of unregenerate bourgeois public, your second or third cousins, who are insensitive to beauty and art. What I call the philistine objection is the objection that the arts are unintelligible; that they are gratuitously complicated and decorative. And to quote something I heard Robert Frost say at his eightieth birthday party, and he's going to speak to you later and I hope he'll say it again, he said he was often asked why he wrote poetry instead of good, honest prose. And he said he had an answer and the answer was he liked to see if he could make one poem sound different from another. But to the literal and the practical mind, poetry, literature, the graces and the decorativeness, the light and glow of painting, seem relatively confusing or unintelligible.

Let me take a very simple illustration. Supposing you are walking of a summer evening with a young lady who is very beautiful and to whom you are greatly devoted, but she happens to be by profession a mathematical statistician. In the calm of the summer's night and full moon you find yourself, perhaps unexpectedly to yourself, murmuring, "The moon is Queen of the Night. The moon is Queen of the Night."

The very sensible young lady looks at you and says, "Nonsense! The moon is a dead star 230 thousand miles from the earth, shining by reflected light. 'The moon is Queen of the Night'! Instead, why don't you talk good, honest prose?"

And then remember that any new idiom in an art, such as a good deal of modern poetry, a good deal of modern painting, is deliberately a variation from conventional, from explicit practice. It seems, as every new movement in the arts, music, and literature, has always seemed, even to those trained in the arts, a heresy, an unorthodoxy, a deliberate throwing the dust in the people's eyes.

The great charge, though, in general, is that if you have something to say, say it plain. Don't put in esthetic curlicues and accents. Metaphor, suggestion, symbol, the half-uttered nuance, the adumbration of something not quite expressed, has always bothered the literal minded, and the literal mind is sometimes in high places intellectually. We've been bemused by the geometrizing intellect, as Bergson called it. We think that whatever can be stated that means anything must be stated in the Cartesianly clear formulas of explicit word....

SUPPOSE we examine these charges: the Puritan charge that the arts promote sensuousness and, therefore, sensuality; that the arts are diversions and distractions from practical and necessary business; and that the arts are diversions and distractions, thirdly, from the clear, responsible lucidities of the intellectual's or plain man's clarity. Those three charges, I submit, by their very nature, lead us directly into the really great and serious issues which the arts not so much raise as exemplify; into the realm of values which are met, encountered, experienced, and not so much defined as displayed in the arts.

How about the first charge? Of course the arts appeal to and exploit the senses. The simple, brutal, minimal fact is that the only way of enjoying music is by hearing it or the only way of enjoying painting is by seeing it. Of course the senses are appealed to, but remember what the arts do is to educate and to discipline the senses to make both more vitally and more clearly aware of what is there to be seen, of what is there to be heard; of reinstating us, making us citizens, so to speak, of the world of perception; restoring to us the disciplined innocence of the eye.

Some of you may be familiar with the famous anecdote of the English painter Turner, who was famous for what then were his revolutionarily nuanced landscapes. At an exhibition of his painting, a dowager walked up to him and said, "Mr. Turner, I never saw a sunset like that."

And he looked at her cooly and said, "Madame, don't you wish you could?"

Painters teach us, each in his own fresh way, which is always a modulation of a tradition. And I may say, having just seen this afternoon the admirably organized exhibition in connection with this section of the course in Carpenter Hall, that a study of just how painters teach us, not by argument, but by delightful example and persuasion to see, is beautifully illustrated in the schools of modern painting represented at Carpenter Hall. There you have a first-hand instance of the way in which the arts refine, discipline, and vitalize our senses.

As to the constant suspicion that the arts are implicitly sexual, that there is an intimation, a resonance of sexual feeling in esthetic experience, we really hardly needed Freud to teach us that. The answer is, "What's wrong about that?" There is a resonance of sexual feeling in all perception. Unlike what we snobbishly call 'among the lower animals,' it's an open season for sex in the human animal all year round. And there is an obbligato and resonance of sexual feeling which undoubtedly has a good deal to do with the intimacy and the poignancy of esthetic feeling. But, again, the arts are not orgies of sexuality. They are quite the contrary: exquisite refinements of sensuous perception with whatever sexual resonance there is.

And how about the charge that the arts are impractical and parasitical; that, in a world in which there is almost universal suffering, still great poverty and misery, and now threats of universal destruction, we cannot find time or take time out for the enjoyment of the arts? Remember that in two important senses the arts are extraordinarily practical. The first sense is that they give meaning to whatever other instrumental values there are in the world. Fanatic Utopians, with a rigid notion of what Utopia is, have always put their Utopia far away. But, if any Utopia came to realization, it would be a realization of certain values to be enjoyed, to be discriminated; a certain vitality, a certain clarity, a certain unification of our experience. And we don't need to wait for Utopia for that.

The arts are constant reminders in the history of civilization in varying accents, in varying modes, in varying styles in music, in literature, in painting, in architecture. They are modes of defining what life is about, what it consists in, what ultimately it is for in the sense of values to be discriminated, to be enjoyed. And remember that it is precisely the creative, the inventive, the fresh, unique language and idiom of each artist, of each work of art, however much there may be traditional and antecedent elements in any work, it is the unique voice, the unique freshness, the unique accent that, like the saints and mystics in religion, helps to keep alive what Bergson called 'an open society,' is a security to us against rigidities, the regimentation of private cliche and of public habit. Emerson long ago remarked that democracy does not consist in caucuses and ballot boxes; democracy consists in the vitality, the freshness, the independence of the individual soul and it happens that what we call genius or creativity in the arts is individuality inexcelsis, is the human soul speaking in an untranslatable freshness and disciplined glory and splendor of its own. And those of us who are not geniuses capture in the experience of a work of art by a kind of osmosis what it means to be an individual, what it means to speak in one's own accent, to be incorrigibly, splendidly and communicatively one's self. And in a world in which the complications of both mechanical and social machinery have tended to make us all duplicates of one another, have tended to make us robots in a mechanized society, the great issue as to whether individuality can survive or not is perhaps best answered not by argument or analysis but by either the experience of a gifted and eloquent individuality in the arts or, to those of us to whom it is opened, making a contribution in the long tradition of individual voices which is a history of human imagination. Remember that in the long run it is indirectly the arts which have both been the heritage of past civilization and have in every epoch, through the voices of individual genius, opened fresh avenues of perception, new ways of feeling, new ways of experiencing, and, ultimately therefore, of thinking about the world.

And that is, perhaps, what above all I meant by saying that in this section of the course you have not left the great issues, you have perhaps approached the greatest issue: the possibility of the fruition of individuality of a life at once disciplined and vital in a free society. Genius in the arts, or the experience of genius, is an esthetic synonym for democracy in political society.

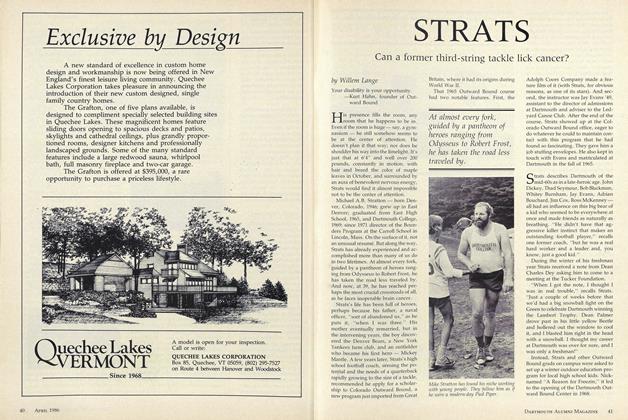

Irwin Edman (left) and Prof Robin Robinson '24, Director of the Great Issues Course

MR. EDMAN, author and Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University, gave this lecture in the Great Issues course on April 12, with the title "The Function of the Creative and the Esthetic in Any Culture." It served as the "keynote address" for the final section of the course dealing with "Humanistic Issues for the Individual," and is printed here from a tape recording. Professor Edman's published works include Philosopher's Holiday, Fountainheads of Freedom, Philosopher's Quest and Arts and the Man, which was required reading in the Great Issues course last year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSinging Ambassadors

May 1954 By ROBERT K. LEOPOLD '55 -

Feature

FeatureThayer School's Fire Bug

May 1954 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureON THE AIR 16 Hours a Day

May 1954 By DONALD R. MELTZER '54 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

May 1954 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, GEORGE E. REDDING -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

May 1954 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1910

May 1954 By RUSSELL D. MEREDITH, ANDREW J. SCARLETT

Features

-

Feature

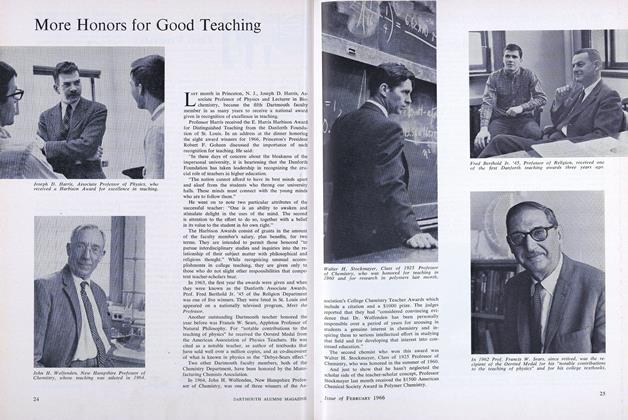

FeatureMore Honors for Good Teaching

FEBRUARY 1966 -

Feature

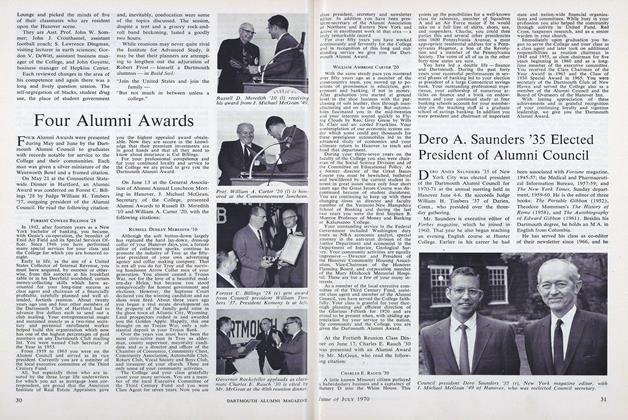

FeatureFour Alumni Awards

JULY 1970 -

Feature

FeatureHere's Looking At It

JAN./FEB. 1978 -

Feature

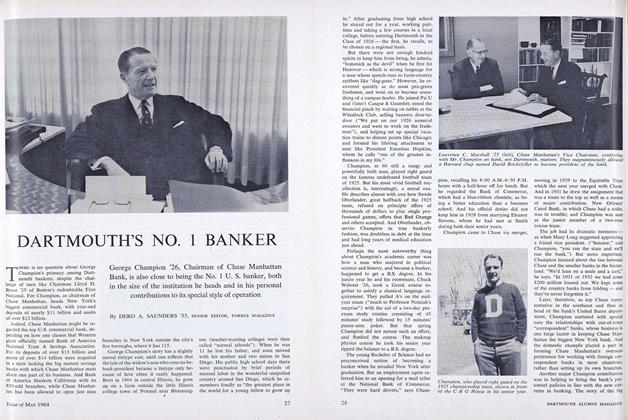

FeatureDARTMOUTH'S NO. 1 BANKER

MAY 1964 By DERO A. SAUNDERS '35 -

Feature

FeatureThe Chief Who Didn't Forget

JANUARY 1969 By Seymour E. Wheelock '40 -

Feature

FeatureSTRATS

APRIL 1986 By Willem Lange