A Dartmouth Professor Who Served as Cultural Attache in Tokyo Discusses Some Aspects of Relations with Japan

PROFESSOR OF BIOGRAPHY

THE nature of a Cultural Attache's duties depends upon a good many things. What the Ambassador thinks about cultural communications is perhaps most important at any given post. If the Ambassador considers them to be important in company with economics and politics, as does Ambassador Reischauer in Tokyo, the Cultural Attache's functions will be various and interesting as well as intimately involved with policy. Professor Edwin O. Reischauer, Director of the Harvard-Yenching Institute, was appointed United States Ambassador to Japan in February 1961. His cultural interests naturally match his unquestioned competence.

If, however, the Ambassador takes little personal interest in cultural affairs, and simply requires such an officer to represent the Embassy at concerts, graduations, art exhibitions, and bazaars, the job may become a dreary round of ghost writing and delivering platitudes on behalf of the Ambassador on occasions that are considered to be not worth the Ambassador's own time.

Nearly everyone he encounters will have a firm body of assumptions concerning what the attache should do, but no two job descriptions look alike, and it is up to the incumbent to find his proper niche for himself, with due regard to the local culture, to the culture and policies of his own country, and to such means as he can find for promoting intercourse between them.

The means available for an American are numerous and varied. They are so much so that he or the Ambassador or the Counsellor for Public Affairs or all three must make a calculated choice of emphasis.

The position in Japan had been vacant for two and a half years when I arrived in November of 1958 after two months of instruction, professionally known as "briefing," in Washington. During my last three days in Washington I had met 45 scheduled appointments in government offices, so that my own mind was for at least a short time thoroughly befogged about choosing anything. Those three days of scuttling about Washington had something like the effect of trying to moisten a postage stamp with a shower bath. The glue was washed off and the paper gone down the hole. Nevertheless there had been two months before that of valuable introduction to the methods whereby a huge organization works toward an end which I considered then and do now to be intelligently conceived and zealously pursued by most of the personnel whom I came to know and respect.

I think the main enterprise is the business of convincing foreign peoples that the people and institutions of the United States are on the whole good neighbors to human freedom and human aspirations. I do not say this is the whole business of the Embassy, which in Tokyo comprised 238 American officers, but I think that at the risk of oversimplifying the matter it is a fair statement of the main object of a Cultural Attache's endeavor. This is worth leaving home for.

One should not in these general terms dismiss the means of promoting the communication, and I wish I might pursue them in more detail. But a general view of the two cultures themselves must first be presented in order to gain some notion of the business in hand of fostering their conversation with one another.

People who have formally cultivated their minds in Japan are almost unanimous in the assumption that America has no real culture of its own. We have but a short history of three hundred years on a soil where all the arts, they say, have been derived from Europe. In this assumption these Japanese appear to limit the meaning of culture to the fine arts, and to exclude, for example, the social arts of self-government by free citizens. Their own culture, in terms of their assumption, was flourishing centuries before ours began even to borrow from abroad. So it is at least logical for them to look to Europe for western culture and to America for politics and commerce and material aid.

The Japanese, on the other hand, have ancient arts of their own which they learned from China and Korea in centuries past and into which they then put their own vigorous and unmistakable character. There can be no question about the integrity of the artistic culture of Japan.

Without for the moment arguing the point about the integrity of modern American music, painting, and literature, let me observe that there is a great gap in what I would call the total culture of Japan, a gap which most Americans find an obstacle to full communication. The Japanese had no experience before the Twentieth Century with popular government, parliamentary responsibility, human rights, or even such rights as the English barons declared at Runnymede. Until 1894 there was no concept in Japanese thought of human rights nor indeed any word for it in the language. The Emperor alone had rights. He yielded the exercise of them to his nobles and major-domos, but they exercised them in his name without ever considering them their own rights, much less human rights in principle.

In the famous Restoration of 1868 all those rights that had been usurped were restored to the Emperor, even taking the minor privileges away from the whole class of Samurai knights. When the Emperor Meiji then granted a Constitution to his people, he graciously caused it to descend, so to speak, upon his subjects as a blessing from heaven, but the subjects still existed solely for the state and not otherwise. When Meiji took away the customary right of the Samurai to lop off the head of any peasant who failed to bow to him, I doubt if he did so for the sake of the human peasant. Rather I believe that the Emperor and his councillors saw a danger to the state in permitting the continued existence of a privileged sort of Praetorian Guard who might help an upstart noble to challenge the Emperor's authority again as they had for centuries past under the usurping Shogun. The Emperor had had no power in those days, but was useful now and then as a mysterious and sacred ghost with whom to frighten one's rivals when they got out of hand. Indeed the present Emperor, Hirohito, was so used in 1941 when the Imperial General Staff bade General Tojo assume the government in the name of the Emperor, whom they kept virtually incommunicado thereafter.

The fact is, then, that whereas Japanese politicians and the press are very noisy about democracy, and the rising generation is eager to throw off all vestiges of Japan's political past, this new democracy is not a thing that they or their forefathers' brought forth upon their islands or ever fought for. It is neither indigenous nor born of their own cultural experience. One result of this is to sever the young peoples' concern for the present from any respect for the past. They want absolute freedom and absolute rights, and have a very theoretical and doctrinaire notion of democracy, just as they are inclined to be intolerant of discipline or tradition in the arts. "The tyranny of the majority" is a familiar catch phrase in Japan today. The spokesmen of this point of view call themselves Progressive Intellectuals, and their dread of having the word Progressive omitted in referring to them is both brash and pathetic.

The older members of university faculties, those with full professorships and a living wage, are inclined to stand aloof from it all and take little part in political faction. They never were heard from effectively in the old days and conse- quently they have no habit of expecting their voices to have public effect now. They have their chairs and their academic specialties. Eminence in the specialty may bring them honors in their old age if they keep out of trouble, but they have no expectation of being invited to partake in the government. Let the shoemaker stick to his last, the scholar to his tomes, and the bureaucrat and the ambitious man run the government.

WITH whom, then, may American culture converse; and what may it expect to gain from the conversation? Our painters and architects may learn from their ancients, and their young intellectuals may learn what they will from our economists and political scientists. But a cultural fact of life remains unregarded on each side. The old arts of Japan were developed by masters who, because their skill and knowledge with natural substances was somehow mysterious, became regarded as priest-craftsmen or craftpriests. They were masters of a cult, and they passed on their lore to their apprentices in mnemonic jingles, for at first there was no writing, and the whole process fitted perfectly into the Shinto pantheon of the spirits of wood, fire, and clay bank. The arts, then, were inseparable from the ethos of old Japan, just as a secular technology is potent within the ethos of the new Japan.

When our art scholars have learned what they can of the arts that flourished in Japan before Columbus discovered America they will have acquainted themselves with a civilization which the Progressive Intellectuals of today reject and repudiate in all its implications. On the other hand, when these same Progressive Intellectuals try to learn from our experience with self-government they do so with little or none of the Greek, Hebrew and Roman assumptions about law and humanity which underlie the whole process of the democratic struggle in the West. The fundamental components are lacking. The fact is that the Marxian dialectic seems persuasive to most of them partly because it repudiates those moral assumptions. The head of the department of economics at Tokyo University, and himself by no means a Marxist, tells me that among all the senior theses and graduate dissertations that have come before him over the past ten years hardly one has failed to be an extrapolation from Karl Marx.

For the sake of contrast and boldness of relief I have here omitted mention of the great arts of the Seventeenth, Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries in Japan. Though there was drama, literature, and great pictorial art in those intervening years the political arts were still essentially a blind spot in the Japanese culture. There is nothing there with which the American heritor of Rousseau, Montesquieu, Locke, Jefferson, Franklin, and Lincoln can well converse unless his hearers desire a one-way lecture, and a lecture which they are hardly prepared to comprehend.

But again looking at the whole Japanese culture of the present day, one observes not only the marked separation of juniors from seniors in nearly every walk of life, but also a well-nigh complete separation and distrust between commercial and political elements on the one side and the intellectual and academic on the other. The only common ground is on the left wing of politics.

Japan is no longer a poor nation. Major building programs go on all over the country and there is scarcely a quarter of Tokyo where the ear is not tortured day and night by the din of pile-drivers and riveting hammers. The motor traffic in the cities, already heavy five years ago, has trebled in the meantime so that there is talk of tunnelling under or cutting through the Imperial Palace to relieve the congestion. An officer of a famous steel company told me last year that his company had been assessed for a voluntary contribution of five hundred million yen, with later an additional three hundred million yen, by the so-called Liberal Democratic Party in power to help defray campaign expenses in 1960. That is well over two million dollars' worth of yen from one steel company in one year as its share in keeping a conservative government in power.

At such a rate it would be absurd to call Japan a poor country. Yet in the universities and schools five thousand dollars in yen covers the total salary of four people in one of the regular governmentsupported universities. Of this the full professor gets thirty-five hundred dollars, and the associate professor and two lesser lights who help to make up what is known as a chair divide the remaining fifteen hundred among them. Living is cheaper in Japan than it is in America, but not that cheap. What is more, university libraries are rarities, each professor usually gathering the books in his subject and keeping them under lock and key, his own together with those in the subject he may receive from the university. This is one of the customary prerogatives of a professor, and his satellites in the four-man chair, those who divide less than half his salary among the three of them, do well if they can borrow his books and eke out an existence in leftwing journalism while they write their commentaries on Karl Marx for the advanced degree. They cannot marry in such conditions, and there is very little about academic life to invite their enthusiasm for the conservative Liberal Democratic Party or for the big business that supports it. Yet it is this Liberal Democratic Party now in power in Japan that fosters the stability required for commercial progress, the meeting of international obligations, and freedom from communist barter schemes. The alienation of affections between the generations in Japan is hardly more extreme than is the alienation of big business and government on the one side from the rank and file of intellectuals on the other. This is especially true of the Progressive Intellectuals.

In these conditions one of the highest heavens for a Japanese student to look to is to win a Fulbright or other alien grantin-aid and get out of his country, if not permanently, at least until his status as a student is past. This is, then, one of the means whereby the cultural officers of our Embassies may promote intercommunication, by the exchange of scholars and lecturers. It is a great asset in the world of culture, but it has its limitations also. Expatriation is not the same as nourishment.

There is a small Department of American Studies in the University of Tokyo, duly authorized by the Ministry of Education, and graduating about a dozen young men a year for the past ten years. All the graduates have readily found superior jobs in government and industry. The Fulbright program has supplied to this department as full-time teachers such men as Arthur Thompson of Florida, Merle Curti of Wisconsin, Saul Padover of the New School for Social Research in New York, and others. A competent Japanese professor of American history, Professor Nakaya, is the director of the little department, and there are a few other Japanese who give part time to it. But the political philosophy and cultural esprit is supplied indispensably by the Fulbright professors from America. The Rockefeller Foundation has subsidized the department over the past five years to the extent of about one million dollars. But to this department in the premier university of the country the Japanese government has at no time allotted more than one thousand dollars in yen per year through the Ministry of Education.

This department of learning is a national asset in the modern Japanese scheme of things. Japan must know more than it does how to deal commercially, politically and culturally with its chief partner and chief competitor. Why then, we may ask, should the support for gaining this knowledge continue to come mainly from America? Why should not Japanese capital support it? The cultural attache must try to maintain a two-way traffic with initiative as well as listening on both sides.

There are of course many other means ready to hand for any cultural attache to keep the traffic moving. There is the vast field of the exchange of books. Obviously this is unlimited in potential. The cultural attache is the Ambassador's representative also on the Fulbright Commission. This is a binational commission administering local policy and supervising the laborious process of screening and selecting ]for recommendation to the Board of Foreign Scholarships in Washington the Japanese candidates for the various categories of fellowships in America, helping to give them orientation, and arranging their transportation. Another large staff under the Commission's supervision deals with the selection and placing of American scholars in Japan. Here there is a considerable responsibility to the Japanese institutions, both with respect to the young American scholars whom they assist in their oriental studies, and to the lecturers and teachers from America who supplement the Japanese faculties and curricula in western learning. The whole association with the Fulbright Commission is a rich one for any cultural attache.

Another absorbing association is with the activities of the twelve American Cultural Centers maintained throughout Japan by the U. S. Information Agency. The directors of these centers are in nearly all instances the sort of people that one takes deep satisfaction in finding as representatives of our civilization. Among their duties is the constant one of presenting to their communities every American artist, scholar, lecturer or public character that comes along, as well as arranging for such tours as those of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Jack Teagarden, the Juilliard String Quartet, Belafonte, or Blanche Thebom. They also arrange local programs of interest to the universities, and call on the cultural attache to hit the road very frequently to give lectures or to act as a foil in panel discussions among American and Japanese scholars. For this exacting life of public relations work these directors have heaped upon them an entertainment allowance of $150 per year. May I add that this was my own operating allowance too. There is no accounting problem, for the allowance is used up in two months or so. The rest is private.

One of the greatest rewards incidental to the office of cultural attache is the varied association with not only the interesting Japanese but also the American visitors whom he tries both to exploit and to help. Who can but congratulate a couple who can bring into association with their Japanese friends such good company as Saul Padover, Paul Tillich, Merle Curti, and Paul Angle, to say nothing of Henry and Beck Williams of Hanover who won many hearts in Japan.

The United States Information Agency, working with our Department of State, holds truth to be the strongest instrument of our national policy. I believe that it holds admirably to that ideal throughout the world. But the question arises frequently, especially when one is working under orders, or even when working alone: Under what conditions might not truth as an instrument lose its sovereignty as truth? Is truth the master or is it the pliant mistress of policy? The individual public servant can never escape this question. No formula can relieve him of the need for eternal vigilance in facing it.

One sustaining idea informs the whole enterprise of cultural exchange, whether for the American academic, or for the diplomatic career officer, or for the friend in a foreign civilization with whom he converses: Where the search for truth is fostered there human freedom is advanced.

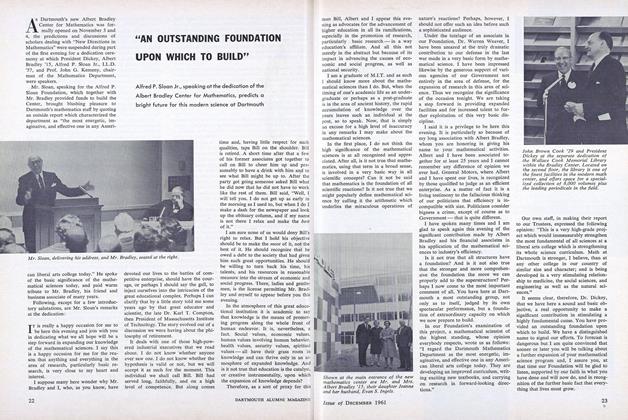

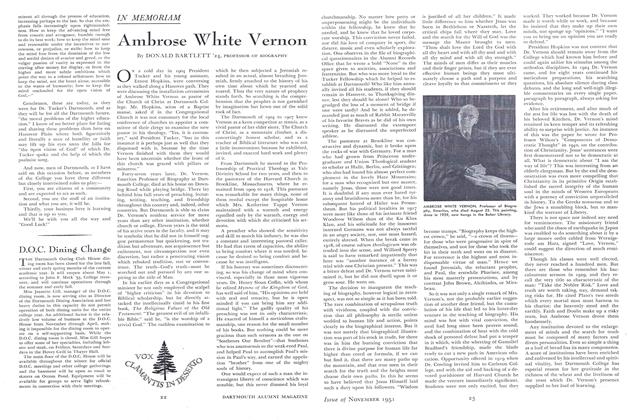

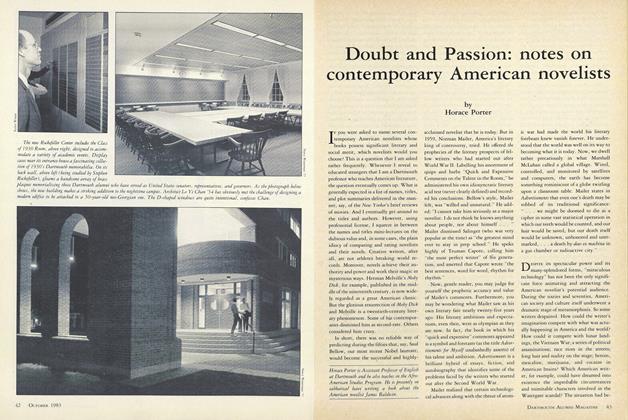

Professor Bartlett at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo

Professor Bartlett, on behalf of the Cityof Miami, accepts an 11-ton statue ofHotei, the Japanese god of plenty.

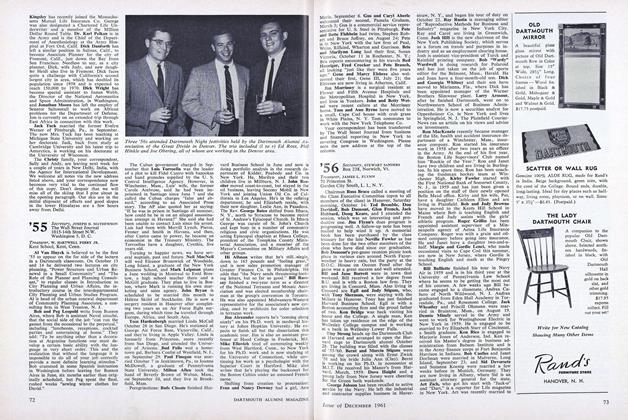

As U. S. Cultural Attache, Professor Bartlett presented the awards in the All-JapanPrince Takamatsu English Speaking Contest. Seated with him (l to r) are Mrs. Bartlett,Princess Takamatsu and Prince Yoshi. Professor Bartlett was born in Japan of missionary parents and came to this country at the age of ten.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

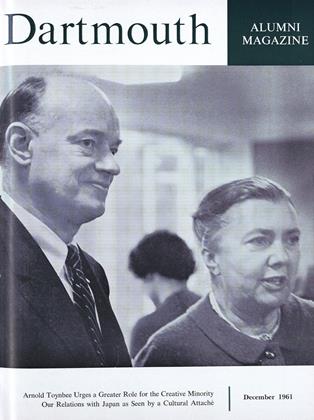

FeatureHas America Neglected Her Creative Minority?

December 1961 -

Feature

Feature30,000 Dartmouth Men Are Her Friendsand Problems

December 1961 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

Feature"AN OUTSTANDING FOUNDATION UPON WHICH TO BUILD"

December 1961 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

December 1961 By STEWART SANDERS, JAMES L. FLYNN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930

December 1961 By WALLACE BLAKEY, HENRY S. EMBREE, JOHN F. RICH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

December 1961 By WILLARD C. WOLFF, JOHN K. BENSON, JAMES B. GODFREY

DONALD BARTLETT '24

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS TO THE EDITOR

March 1934 -

Article

ArticleClassicist Not Without Honor

February 1941 By Donald Bartlett '24 -

Article

ArticleAmbrose White Vernon

November 1951 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Books

BooksADVENTURES IN BIOGRAPHY.

November 1956 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Books

BooksALL THE BEST IN JAPAN AND THE ORIENT INCLUDING HONG KONG, MACAO, TAIWAN AND THE PHILIPPINES.

JUNE 1964 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Books

BooksBIOGRAPHY PAST AND PRESENT: SELECTIONS AND CRITICAL ESSAYS.

FEBRUARY 1966 By DONALD BARTLETT '24

Features

-

Feature

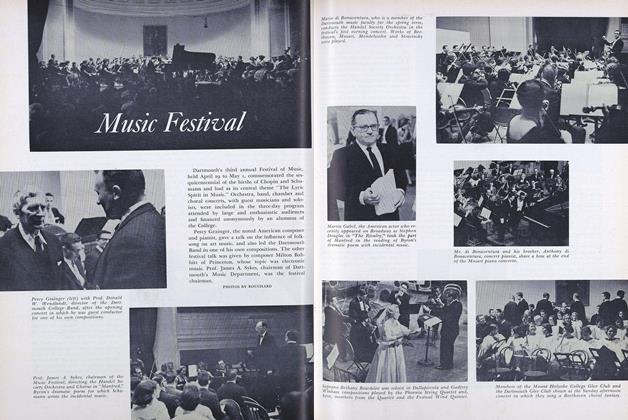

FeatureMusic Festival

June 1960 -

Feature

FeatureDE Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Feature

FeatureHanover Inn

April 1975 -

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

OCTOBER, 1908 By Horace Porter -

Cover Story

Cover StoryParadise Regained

MARCH 1995 By Jere Daniell '55 -

Feature

FeatureLet There Be Color

May/June 2013 By Sean Plottner