PRESIDENT EMERITUS OF THE COLLEGE

It is not an uninteresting fact that this meeting now marks the 100th anniversary of the first formal organization of the alumni of Dartmouth College, which occurred in 1855. There has always been a community of interest among Dartmouth men whether organized or not and the problem from the beginning was simply how to focus this.

There is a certain hazard in inviting to discuss alumni affairs of the past one who was so intimately connected with the pre-Alumni Council days as I was. The temptation to run wild in reminiscence is very great. The establishment of this Council was a somewhat prolonged, somewhat complicated and very rewarding experience in which to have been involved.

I have always thought President Lord's comment at that first alumni meeting, a hundred years ago, was as eloquent in regard to the place of the alumni in the college scheme of things as anything I have ever heard or read. As part of a somewhat extended statement he said, "You ask me to show cause why Dartmouth should continue to have the favor of her sons. My answer is a short one. Because Dartmouth is in her sons. There is no Dartmouth without her sons. They have made her what she is and they constitute good and sufficient reason why she should be sustained and become yet more prolific and propitious a mother." I don't know how the whole proposition could be encompassed in fewer words or be put more aptly.

It used to seem absurd to me even when I was an undergraduate, and especially when as editor of The Dartmouth I was reading contemporary college publications, to read of the grouchings of college administrators or of certain faculty groups in regard to alumni. I could never figure out to what purpose the College existed if it wasn't for the production of alumni. I still hold to that conviction and I am

conscious that in my commitment to that belief lies not only the motivation which led to the organization of this Council but to the policies which later dictated my administration as President. In my opinion the onus is upon a college in very considerable degree if not entirely for the kind of an alumni body which it has.

The alumni organization at Dartmouth was not a rapid development and was not attained without the efforts of many men and many groups down through the years from 1855. For long periods the whole movement seemed to be inert if not dead. President Lord, an extraordinarily able administrator, who brought about the first alumni organization nevertheless became a Civil War casualty because of his Fundamentalist theological beliefs.

Sometimes when I have heard discussion of Dartmouth's liberalism, as though this was a new attribute of the College, I have thought of the warfare President Lord carried on against Northern sentiment, against the Abolitionists, his defense of slavery, and his criticism in time of war of the government, continuing into 1863. Only then did the Trustees yield to outside sentiment and urge him to forbear - which he would not do but instead resigned. He believed that God had instituted slavery through his condemnation of the dark-skinned sons of Ham and that any attempt to lighten their load to lift the curse upon them was warring against the will of God.

In such time there was, of course, no possibility of unifying alumni sentiment or of carrying towards completion any form of alumni organization. For three decades to come the inarticulate longings of some of the alumni for a closer relationship with the College and the active dissatisfaction of others because nothing was being done awaited a militant leader.

There were, to be sure, occasional outbreaks now and then of aggressive groups in protest against their lack of voice in College affairs. In 1881, for instance, the discontent of the New York alumni with existing conditions became so great that they arranged for and staged a trial in Hanover of President Bartlett for maladministration with all the trimmings of a formal court trial. The New York alumni presented a distinguished array of counsel including among others a leader of the New York Bar and the United States District Attorney of New York. President Bartlett on his part was represented by two distinguished north-country lawyers, both Dartmouth men, who suffered from no inferiority complexes as they faced the metropolitan groups against them. Whatever else this trial was it was an extraordinary manifestation of the existent discontent with the established College government represented in the Board of Trustees.

In later years I came to know many of the people involved on each side, and testimony was completely in agreement on one point, that of all the parties concerned the least perturbed was President Bartlett who suggested no reluctance in the matching of his wits against those of his opponents and proved eminently successful in doing so. By his skill, as Richardson said in his history, the President reduced the charge "from what might appear to be a serious offense to the dimensions of a trivial complaint."

Even after all this turmoil no agreement was reached and nothing was settled that would affect the fundamental discontent of the alumni in having no representation on the Board of Trustees or officially elsewhere. So the disorganization went on for another decade. In years long after it used to seem to me that the great misfortune to Dartmouth in all this was that during the years when great fortunes were being accumulated and lush money was being made, from which great endowments were sprouting, as at Harvard and Yale, the internal wrangling among Dartmouth men exhausted their energies and depleted their loyalties. This went so far that it completely paralyzed any efforts to capitalize enthusiasm that was potentially available in the alumni body. It denied possibility of establishing public relations that would make for high prestige and attract major financial support outside.

' I ,HE story of the continuing agitation of -1- the alumni for representatives of their own choice on the Board of Trustees and of the resistance of members of the Board individually and collectively is a long one and very involved. Briefly, however, in 1890 the death of Judge Nesmith of the Class of 1820, in his 89th year and in his thirty-second year of service as a Trustee, created a vacancy to fill which the alumni determined to demand the election by the Board of a man of their own choice. No selection was ever more fortunate, as later years revealed, for the alumni presented the name of Frank S. Streeter of the Class of '74, and argued with vehemence and logic for his election. But the idea of electing a mere youth, sixteen years out of college, to succeed the venerable Judge Nesmith who had graduated from Dartmouth nearly a quarter of a century before Mr. Streeter was born was too much for the Board to accept. And even more, many members of the Board, with reason, were suspicious of the nominee's theological orthodoxy at a time when any scepticism of validity of such orthodoxy was anathema to most college governing boards.

Parenthetically, as late as the early 1920's Dr. Tucker told me that if he had realized in 1893 the extent to which his having been a defendant in the Andover heresy trial of the late 1880's would prove a handicap in recruiting enrollment for Dartmouth, during the early years of his administration when increased enrollment was essential, he would have hesitated for longer even than he did before accepting the Presidency of the College.

The Board's rejection of Mr. Streeter's name in 1890 and the election of another, both in the speed and the manner in which it was done, created an exasperation among the recalcitrant alumni so violent and so insistent that the Trustees were forced to the conviction that it must be given attention and that some compromise had to be offered. Having so decided, their eventual offer to the alumni was more generous than had been demanded. It was agreed that the Board would provide five vacancies within the next two years, to be filled by nominees of the alumni for staggered terms of five years each, so that eventually there would be one vacancy a year to which the Board would presumably elect the nominee of the alumni. This proposal offered the alumni half the membership of the Board aside from the President and the Governor of the State. Three fine men were nominated by the alumni and elected to the Board in 1891 and two more, including Mr. Streeter, in 1892, thus completing the reorganization of the Board for which the alumni had clamored for decades. Thus was established comparative calm between the official College and the alumni. Here actually began the alumni movement ever increasingly strengthened in the affairs of the College and so strikingly evident in this meeting here today.

If I had had hesitancy on other grounds about accepting your invitation to speak here today I still would have wanted to come to pay tribute to Frank Streeter and to emphasize the debt Dartmouth owes to him, not only as the most potent sponsor for alumni participation in affairs of the College but as a contributor of incalculable value to the Board of Trustees and unofficially as right bower of Presidents in three administrations from 1892 to 1922.

Second only to Dr. Tucker, appreciation should be given to him for laying the foundation of the so-called "new Dartmouth" that dates from Dr. Tucker's inauguration in 1893. The administrative direction of the College, its policies and its practices, set a pattern during the years of Dr. Tucker's administration to which in general each succeeding administration has conformed in bringing the College to its status of the present day. And in these early days when the natural instincts of the Board of Trustees was for excessive caution if not inertia, Mr. Streeter was ever by Dr. Tucker's side, militant and aggressive for any move that promised College welfare or the advancement of Dartmouth's prestige. And too he was, as was then most needful, a very practical operator who knew the relative advantages of controversial argument or mellifluous persuasion to different situations. In regard to use of these he did not have as much reservation as Dr. Tucker might have had if only he knew they were essential to support progressive policies and induce courageous action on the part of a hesitant Board.

I inherited the regard and affection for him that Dr. Tucker held and in later years I came to feel a like sense of dependence on him. Many a Trustee down through the years has qualified as an unsung hero of the College but never one more so than he. From my own earliest suggestions in regard to alumni organization there was never a plan conceived or a project undertaken without conference with Mr. Streeter so long as he lived, and that was particularly true in regard to the establishment of this Council.

No other man than Dr. Tucker could have so completely met the needs of the College in 1893. Nothing except an assumption of the oversight of Dartmouth's affairs by a solicitous Providence can explain Dr. Tucker's willingness to accept the Presidency of the College at that time. Trustee of the College for fifteen years before coming to its Presidency and respected by all of his fellows, yet avowedly sympathetic with the critical alumni attitude of times past, he was the ideal choice for the position. But no explanation except his deep sense of obligation to the alma mater he loved can explain his willingness to plunge from the comfortable haven of work he most enjoyed and a congenial atmosphere into the toil and conflict he well knew would be essential to the rehabilitation of the College, torn by dissension and paralyzed by inertia for decades previously.

He was the kind of man one meets occasionally in life who possesses the common denominators of greatness; he would have been outstanding in any field of human activity to which he might have committed himself. As among college presidents I have known with some intimacy over a period of more than half a century, some of them very great men, I have never known one who commanded from undergraduates and alumni whom he had graduated the combination of respect, veneration and affection that he came to possess. I have had a happy life marked by good fortune but outside of my home life I have never had anything that approached the privilege of working under his direction. There was no diminishing of size or littleness of character to be revealed by intimacy with him.

So it was that when after a time he directed me to make a study of alumni organization at other colleges and to make recommendations for its development here, I accepted the assignment eagerly, partly because I knew that any effective accomplishment would be the realization of a long-time aspiration of his in behalf of the College and partly because I had come to realize that to capitalize alumni strength Dartmouth men must be fully informed in regard to College policies and affairs and must through greater representation become more largely participants in these.

The first conclusion to which we came was that any expansion of alumni organization ought to be developed around some existent alumni group. First we considered the General Alumni Association but this seemed too nebulous on the one hand and too clumsy on the other to serve as the nucleus of a greatly expanded organization. Finally it was decided to invite the secretaries of classes and clubs to a conference in Hanover to consider the whole program and to determine whether they would be willing to organize to sponsor it. This was on the theory that a house of delegates, so to speak, made up of elected representatives of classes and clubs, would be the clearest approximation available to a popular alumni body.

This meeting was held in Hanover on January 21, 1905, and proved even more successful than had been anticipated. One of the important results was an awakened interest among the secretaries in their own responsibilities as representatives of their classes and clubs. In a few cases where men did not feel that they had the energy or the time to meet such obligations they withdrew and were replaced by more active workers. But unanimously they expressed enthusiastic interest in hearing periodically from the President and associated officers in regard to administrative affairs, faculty accomplishments, undergraduate attitudes, athletic policies and kindred matters.

A year later President Tucker felt justified in saying to those gathered for the second annual meeting, "In the last year there has been nothing more inspiring than our recollection of the first annual conference. It was a distinct reidentification of the alumni with the College. We now, as never before, have the promise of the actual unity which we all desire. We are not expected to analyze our college spirit but we are expected to give it substantial form and expressive force."

Working from then towards our final objective, successive steps were taken such as the establishment of an alumni magazine and alumni sponsorship of a fund to be initiated and conducted by the alumni and proffered to the College. But Dr. Tucker's illness, the eventual necessity of his yielding to this and resigning, and the incoming of a new administration all necessarily delayed discussion of the desira- bility of establishment of an Alumni Council such as we have here today, heading up and binding together all alumni groups.

However, President Nichols early in his administration expressed interest in such a project and in his first meeting with the Secretaries Association in 1910, according to the record, "raised the question as to whether some further organization of the alumni was possible for yet closer connection of the alumni and administration of the College."

It was then voted, "That the Association of Secretaries express its opinion that the interests of the College would be further served by the formation of some representative organization of the alumni, supplementary to the General Alumni Association, whose concern it should be to bring all the alumni and the College into still more intimate relations."

It was further voted that a committee of five be appointed to investigate and report to the Secretaries Association and if approval was expressed therein to submit the project for consideration of the General Association of the Alumni. These steps were taken. Successively the Secretaries Association and the General Association of the Alumni gave approval to the organization of such a body. It was organized and in 1913 its first meeting was held in Philadelphia and its career of usefulness to the College began developing cumulatively to this day.

And what of the half-century feud between alumni and Trustees? Few know in these times that such ever existed. At the second meeting of the Council in Philadelphia in 1914, Mr. Streeter spoke representing the Trustees: "We understand that some doubted the expediency of such a country-wide organization and were pessimistic as to its practical working value; also that others questioned the attitude of the Trustees toward such a body. I come to dissolve those doubts as far as the Trustees can do so....

"We believe that this Council should be regarded as permanently established and should be dignified and strengthened by placing upon it responsibilities as large as may be permitted by the nature of the respective relations, legal and otherwise, of the Trustees and Alumni to the College and to each other."

So it has been and so it is today!

Mr. Hopkins at the Hanover meeting of the Alumni Council in January

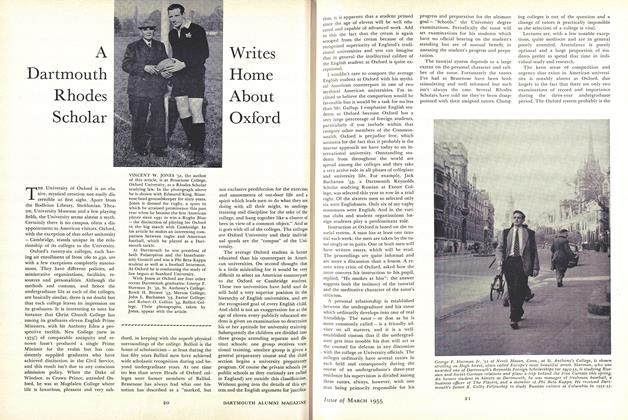

FRANK S. STREETER '74 (right), to whom Mr. Hopkins pays tribute as a powerfulsponsor of alumni participation in College affairs, shown in 1920 at Dover Point, N. H.,with (l to r) Governor John H. Bartlett '94, Ralph D. Paine and President Hopkins.

winning fraternity snow statue for Carnival was Phi SigmaKappa's "Whalerace," a take-off on Liber ace.

North Fayerweather's "Sextapus" was awarded the first prize in thedormitory snow statue competition.

This article is based on the extemporaneous talk given by President Emeritus Hopkins at the January 15 meeting of the Dartmouth Alumni Council in Hanover. For publication in the ALUMNI MAGAZINE the tape recording has been somewhat condensed and revised by Mr. Hopkins.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth Rhodes Scholar Writes Home About Oxford

March 1955 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929

March 1955 By CHRISTIAN E. BORN, EDWIN C. CHINLUND -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1955 By G. H. CASSELS-SMITH '55 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1955 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES JR., TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1955 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Launches General Campaign Among Alumni

OCTOBER 1969 -

Feature

FeaturePapa's Son

OCTOBER • 1986 By Everett Wood '38 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1971 By honoris causa. -

Feature

FeatureStaying Clear

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Jeanet Hardigg Irwin '80 -

Feature

FeatureWHEN THE YOUNG TURKS CAME

December 1990 By John G. Kemeny -

Feature

FeatureThayer School's Centennial

OCTOBER 1971 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '28