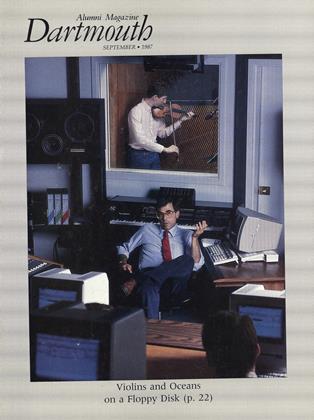

A Dartmouth professor explains how electronics have changed the music industry and made the traditional music major obsolete.

IMAGINE for a moment the sound of a woman singing, then the sound of the ocean. Now imagine the sound of the ocean singing. That is just one of an infinite number of sounds possible from an astonishingly sophisticated new generation of electronic instruments. Little did I think, ten years ago, that a machine I helped design would lead to this, and would cause a a monumental change in our music culture. Consider these points:

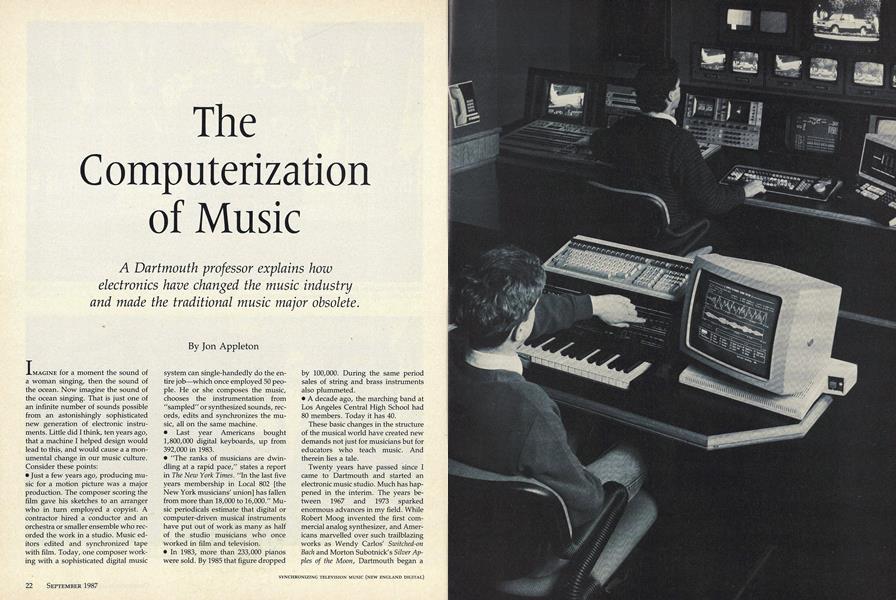

• Just a few years ago, producing music for a motion picture was a major production. The composer scoring the film gave his sketches to an arranger who in turn employed a copyist. A contractor hired a conductor and an orchestra or smaller ensemble who recorded the work in a studio. Music editors edited and synchronized tape with film. Today, one composer working with a sophisticated digital music system can single-handedly do the entire job—which once employed 50 people. He or she composes the music, chooses the instrumentation from "sampled" or synthesized sounds, records, edits and synchronizes the music, all on the same machine.

• Last year Americans bought 1,800,000 digital keyboards, up from 392,000 in 1983.

• "The ranks of musicians are dwindling at a rapid pace," states a report in The New York Times. "In the last five years membership in Local 802 [the New York musicians' union] has fallen from more than 18,000 to 16,000." Music periodicals estimate that digital or computer-driven musical instruments have put out of work as many as half of the studio musicians who once worked in film and television.

• In 1983, more than 233,000 pianos were sold. By 1985 that figure dropped by 100,000. During the same period sales of string and brass instruments also plummeted.

• A decade ago, the marching band at Los Angeles Central High School had 80 members. Today it has 40.

These basic changes in the structure of the musical world have created new demands not just for musicians but for educators who teach music. And therein lies a tale.

Twenty years have passed since I came to Dartmouth and started an electronic music studio. Much has happened in the interim. The years between 1967 and 1973 sparked enormous advances in my field. While Robert Moog invented the first commercial analog synthesizer, and Americans marvelled over such trailblazing works as Wendy Carlos' Switched-onBach and Morton Subotnick's Silver Apples of the Moon, Dartmouth began a research project that later evolved into the instrument known today as the Synclavier.

My role in its development was that of a musical instrument designer. I envisioned a new performance instrument, but I wasn't an engineer. Thus began a collaboration with Thayer School engineer Sydney Alonso and Cameron Jones '75, a student of music, computer programming and engineering. I dreamed up ways the instrument could be used, set criteria for how a musician would talk to the machine, and counseled the pair of engineers as to what sort of features musicians would praise and what limitations would be unacceptable.

The year 1973 was a milestone: it marked the introduction of the first minicomputer. Up until then, computer-synthesized music required a large, general-purpose computer known as a mainframe. The early minicomputer, however, was too small to use as a sophisticated sound generator. Alonso solved the problem by inventing a separate digital soundproducing device which translated the composer's specifications into instructions a computer could understand. Jones programmed the minicomputer.

As the prototypes were built, I composed new works demonstrating that intelligent, sophisticated music could be written, produced and performed on this new instrument. We called our machine the Dartmouth Digital Synthesizer. Our first record, titled "The Dartmouth Digital Synthesizer," was released by Folkways Records in 1977.

After Alonso and Jones left Dartmouth to form New England Digital Corporation in 1976, the collaboration continued, ultimately leading up to the Synclavier—the first commercial digital musical instrument. My formal association with New England Digital ended that same year. At the time I was on leave from Dartmouth, and when the year ended I returned to academia because teaching and composing were what I loved most. (See the box on page 27.)

Today New England Digital is considered the most respected manufacturer of advanced digital musical equipment in the world. Artists such as Chick Corea, Frank Zappa, Leonard Bernstein and Sting use Synclaviers, and the machines have become standard equipment at hundreds of commercial studios. As a result, I find myself facing an exciting educational challenge.

Learning the Synclavier, or another electronic instrument, is an extraordinarily complex process. Normally the machine is run by one person. Teaching someone to use it has been a bit like a piano lesson. The teacher sat at the pupil's side and coached, prompted and corrected. But that is all in the past, at least at Dartmouth. With renovation and relocation of the Bregman Electronic Music Studio inside the Hopkins Center, Dartmouth leads the way in this area of musical education.

The Bregman Studio is the only facility of its kind in the nation. The combination studio and classroom enables me to teach 16 students at once. Each student sits at a work station equipped with a Macintosh computer and a pianolike keyboard. All work stations are part of a network, the centerpiece of which is a $500,000 Synclavier, the latest model.

For the music student who spends a term learning to master the technical aspects of electronic instruments, a new avenue of musical composition is suddenly opened. Most people think that the art of composition can be practiced only after years of conservatory training. There is an assumption that music was made by great masters from the past and that ordinary humans can't compose great music. These attitudes, until recently, have inhibited music students.

On the other hand, electro-acoustic music (the current term for the various types of electronic music) has so little tradition behind it, when compared to instrumental music, that young composers feel far less restrained in expressing their own ideas. Computer technology gives the composer a myriad of new sounds to work with. The relationship between a modern composer and a synthesizer is similar to that between Beethoven and his thennovel instrument, the piano forte: the new invention enables a composer to create a new musical experience. The Wenger Corporation, a distributor of music-education products, tantalizes potential customers with this sales pitch: "A good software program literally pulls out all the stops. It takes the lid off your brain. It frees your fingers, your thoughts, your time and energy for the art of composing and the craft of editing what you write. Imagine what Beethoven or Mozart might have done with a Mac, a mouse, and a synthesizer."

Of the 1,250 students who have composed music in my classes during the last two decades, 250 have gone into advanced courses in composition and worked in the Bregman Electronic Music Studio. I want to emphasize here, however, that my main purpose in teaching has not been to produce more composers but rather to give students the experience of composition.

More importantly, the success, sophistication and widespread use of the Synclavier and other synthesizers dictate that there should be changes in the very way music is taught. At Dartmouth, an introductory-level student can still take a class in Western Music, but there is also the option of taking a class titled Music and Technology. Among the topics we cover are instrument design, sound synthesis and the role of computers in contemporary music culture.

Dartmouth, however, is in the mi- nority. Amazingly, of the more than 1,500 institutions of higher education in American that have music pro- grams, only a quarter offer instruction on synthesizers. Even fewer provide electric guitar lessons. Yet these are the instruments of our time, and the ones played by most undergraduate musicians.

It is a cause for alarm that at most colleges and universities, music faculty are unaware of these momentous changes. The academy should not only be responsive to cultural change. They should also recognize that they are training musicians and music educators who will no longer have jobs when they graduate. I am not advocating discarding that body of musical knowledge which is the foundation for music programs in the liberal arts, but I do argue that this foundation be augmented with classes and training on modern instruments as well.

The worlds of music and education have never been so far apart as they are today. Educators must realize that the major difference between music today that of the last three centuries is that amateur composers have unprecedented opportunities. Young people are approaching music with a more playful and inventive bent. Musical technology has made the search for virtuosity meaningless (who cares how fast and flawlessly you can play a keyboard instrument when a computer can do it better?) and has forced people to confront their own potential for originality.

The issue is not that machines instead of people are making music. Rather, the young musician today is growing up in a different musical world from the one their teachers knew. The decline in chamber music concerts, the financial bankruptcy of major symphony orchestras (including Oakland and San Diego), and the surfeit of recordings of traditional symphonic music indicate that only a few leading conservatories will be needed to train traditional musicians. We are obligated to teach people about the culture in which they live; we cannot go on living in the past.

No need for Memorex: The Synclavier writes the sounds of saxophonist Fred Haas '73 directly to a computer disk. Many commercialstudios have replaced their multi-track tape recorders with Synclaviers because the machines offer superior recording and editing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMystery on the Mountain

September 1987 By Daniel Q. Haney -

Feature

FeatureDiary of a Long Distance Runner

September 1987 By Tim Hartigan '87 -

Feature

FeatureThe Speech

September 1987 -

Feature

FeatureHeeding the Beat of a Different Drummer

September 1987 By Teri Allbright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1976

September 1987 By Martha Hennessey -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

September 1987 By Kenneth M. Johnson

Jon Appleton

Features

-

Feature

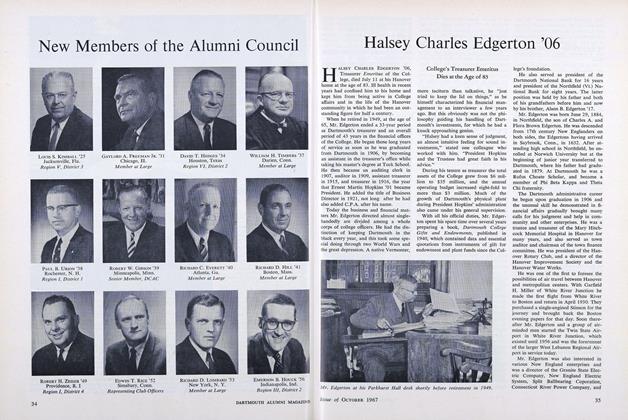

FeatureHalsey Charles Edgerton '06

OCTOBER 1967 -

Feature

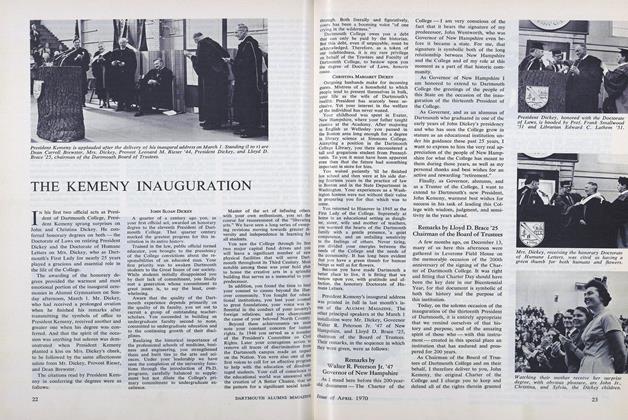

FeatureTHE KEMENY INAUGURATION

APRIL 1970 -

FEATURE

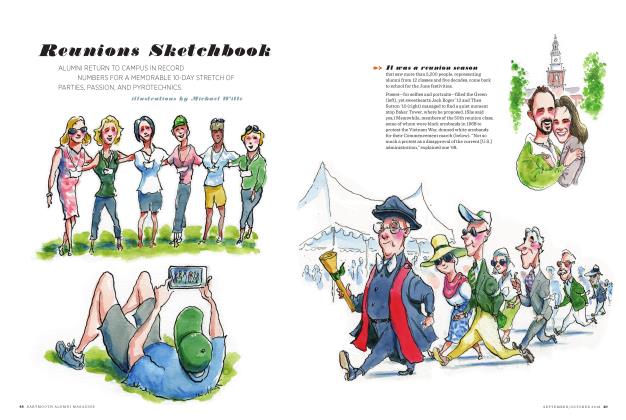

FEATUREReunions Sketchbook

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 -

Feature

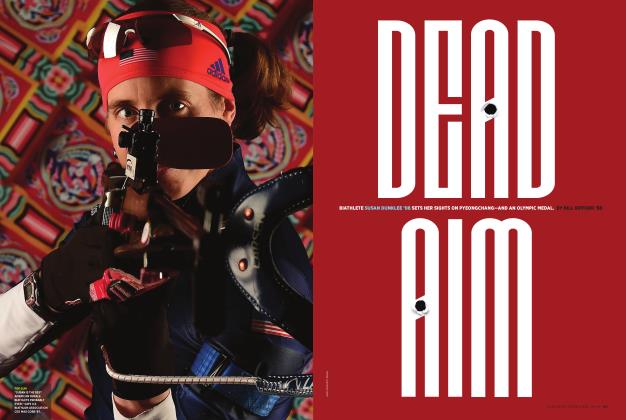

FeatureDead Aim

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2018 By BILL GIFFORD ’88 -

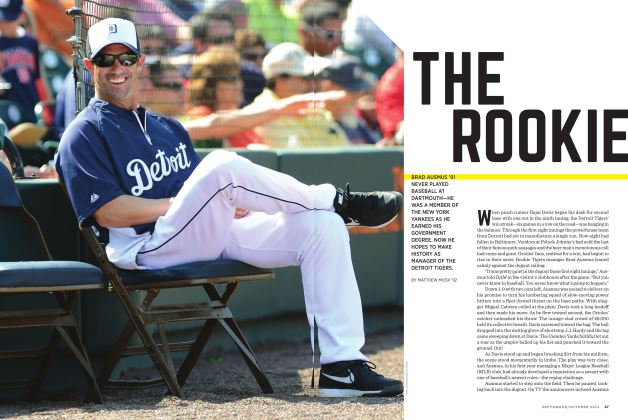

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Rookie

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

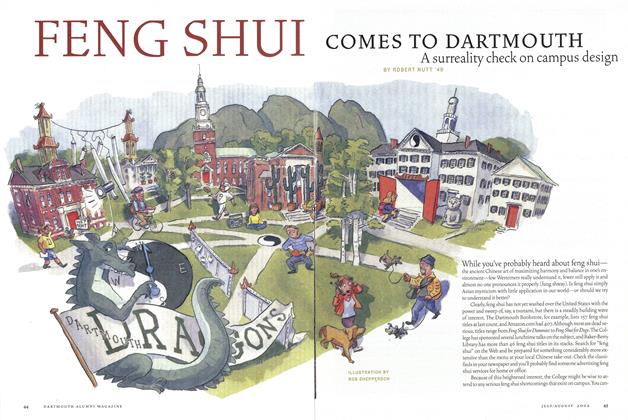

Feature

FeatureFENG SHUI COMES TO DARTMOUTH

July/Aug 2002 By ROBERT NUTT '49