PRESIDENT Dickey and Trustees of the College, Members of the Faculty, Honored Guests (including, of course, the families and friends of the graduating class), Men of the Class of 1956:

On your behalf, it is my duty to give to the College our Valedictory. We are saying good-bye to a place where we have lived the better part of the last four years of our lives, spending Dad's money and taking part in a common intellectual experience. We've done our last assignment, attended our last class, struggled over our last paper, filled our last blue book, and enjoyed the last weekend at Bennington. And when we receive our diplomas in a few minutes, we will have formal recognition by the College that we have done all these things in a satisfactory manner and are now free to go.

At this time it is customary to think a little bit about what we have gotten out of our college careers. Just what has all our time and energy and money netted us? What have we learned?

The most important part of our learning has probably been the many issues and problems of our time: racial segregation, the crisis in our schools, the need for honesty and integrity in government, American foreign aid policy, and the question of coexistence with the Communist world.

A few days ago a classmate and I were talking about the lecture all the seniors heard by Mr. Harry Schwartz, specialist on Soviet affairs for The New York Times, on "The Challenge of the Soviet Union." Mr. Schwartz told us how Russian students were being trained primarily to serve their country. We agreed that we would like to do something for our country, but we couldn't see how we would ever get the opportunity.

I suppose many of us feel right now that we want to do something for the good of society. Our college experience has included some periods when this desire was especially strong, when our ideals seemed particularly near and real for us. Perhaps a lecture was especially meaningful. Perhaps it crystallized some things for us; or carried some special significance that made us walk out of the class with a feeling of exaltation and wonder, as if we had been lifted to a great height. Perhaps it was when we were walking across the campus from the library late on some clear night when the snow was on the ground and on the branches of the trees, and the stars were shining above. Perhaps we were sitting in our room one night reading an assignment, with classical music playing, snow falling outside, and we came across a passage that held a distinct meaning for us: the thoughts and ideas of a man, long dead, who was trying to wrest some meaning from the chaotic and confused context of his times. We had a feeling of excitement, of inspiration, a desire to do something fine and noble with our lives; a hope of making the world a better place.

Will we ever get the opportunity to do something like this? Konrad Adenauer recently said that the most important thing to do is the job at hand.

All of us cannot be presidents and chancellors and ambassadors. It is probably safe to say that the majority of us are going into the business and professional worlds. And Herr Adenauer points out that we need to remember that great world ideals all begin in some home neighborhood. He tells us, "When we put inspiration into raising our family; or do the shop work better than required; or make the town a model for others, then our influence spreads in widening circles."

Since there are few problems facing our society that do not reach down into community life, there will be opportunities all around us to do something. We can volunteer to be an agent for the Community Chest drive; we can serve on town planning boards for the improvement of our communities; we can serve on the school board or on the city commission; we can teach a Sunday School class; we can be Scoutmaster for a Boy Scout troop; we can continue to read, keep ourselves informed, and vote. On the school board we will have the most vital role in the process of providing adequate, universal education; as workers on the various community service projects, we provide for the welfare of that segment of society represented by our own home town; by voting we try to improve the quality of government and to influence its policies at home and abroad. So we will have the opportunity.

However, the next and most crucial question, one which we probably will not think of seriously until later on, if we ever really articulate it, is: Will I take that opportunity? Will I take advantage of the opportunities at hand to make the world a better place?

Let's face it. Things are going to be different when we get away from these ivycovered walls and the ideals of the classroom; when we come out of our quiet rooms where we listened to classical music and watched the snowfall outside; when we actually get out into life and start paying bills. Because we're going to find that there is not now and never haS been too much money in heading a Community Chest drive or being a Scoutmaster. Moreover, the road to national fame by way of community service is a hard and long one: after all, Konrad Adenauer was seventy before he was elected Chancellor. And, finally, there is very little glamour and glory connected with these homely tasks when you compare them, for instance, with Dag Hammarskjold's mission to prevent a war in the Middle East, or Chief Justice Warren's decision abolishing segregation in the public schools.

It's going to be hard to remember the great ideals that were so real to us once: that made us want to do something great and noble and wonderful; that made us want to leave the world a little better for our having been here.

Anyway, we won't have time, really, with the demands of business and raising a family. Time will pass and our memories of college days will fade. And we'll retire with substantial bank balances and go to Florida. And perhaps, from time to time, we'll remember the ideals and ambitions we once had ... and think of them, maybe a little wistfully ... maybe indifferently.

William F. Behrens '56

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1956 -

Feature

FeatureThe 1956 Commencement

July 1956 By FRANK PEMBERTON -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1956 By THURLOW M. GORDON '06 -

Feature

FeatureGeorge Nickum '31 to Head Alumni Council for 1956-57

July 1956 -

Feature

FeatureThree Alumni Honored For Service to College

July 1956 -

Feature

FeatureJohn D. Rockefeller Jr. Gives $1,000,000 To Fund for Building the Hopkins Center

July 1956

Features

-

Feature

FeatureYOU CAN LIVE WHERE FOGHAT SANG

APRIL 1989 -

Feature

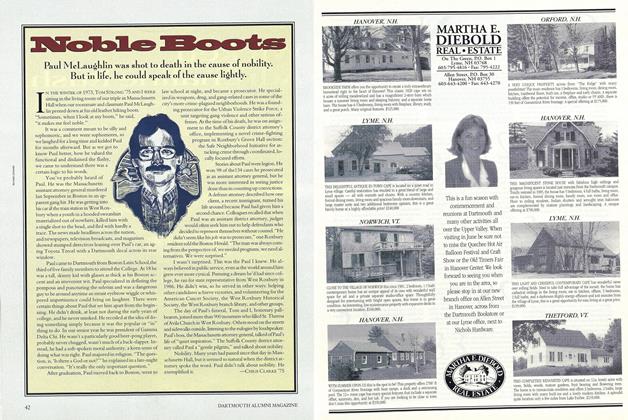

FeatureNoble Boots

JUNE 1996 By Chris Clarke ’75 -

Feature

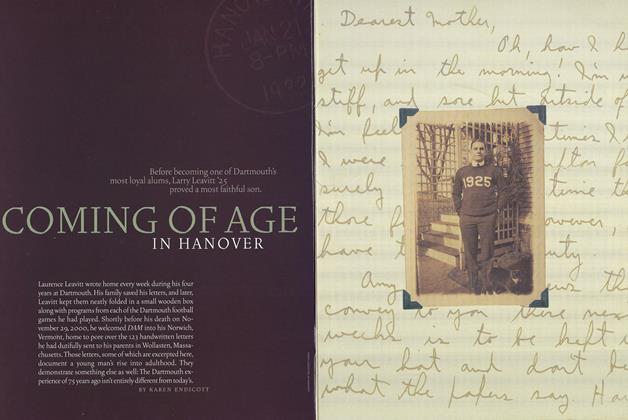

FeatureComing of Age in Hanover

Nov/Dec 2001 By KAREN ENDICOTT -

FEATURE

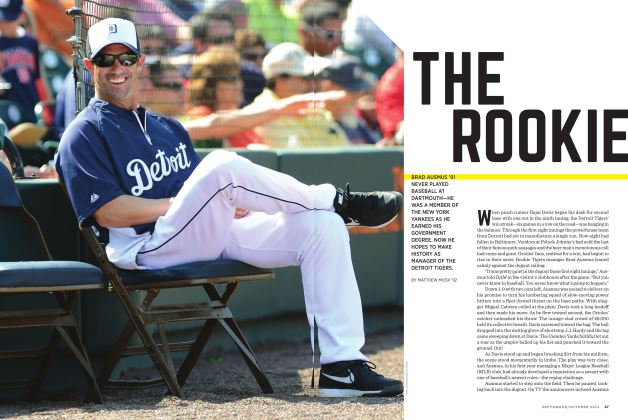

FEATUREThe Rookie

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2014 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureThe New New York

Jan/Feb 2002 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Features

FeaturesGreatest Hits

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2023 By Ty Burr