ONE evening last spring, following the Dartmouth Glee Club Concert in Portland, Oregon, I gave a cocktail party in my bachelor apartment. All of the fourteen persons present were Far Western residents. The center of attraction was a tall, well-built, copper-skinned, black haired but slightly graying man of 56 who, while the glasses were being balanced, held the attention of all with his talk of Indians, their way of life, problems and future, and accounts of his life among them, his people, on the reservations.

The average urban Far Westerner knows little more about Indians than does his Eastern counterpart. All too frequently he has inherited the pioneer attitude of scorn and contempt for the Indian as an intellectual equal. For my guests it was a unique experience to be associating socially with a "redskin" who could talk to them with aplomb, who could refer to an educational past at Phillips Andover Academy and Dartmouth College, who recounted tales of forming athletic teams, musical groups and even bridge clubs on the reservations, who had founded agricultural fairs and who argued with logic and plausibility for the greater integration and acceptance of the American Indian as an equal in American life. This, by the way, is the new policy of the United States Indian Bureau.

Frell Owl '27, who by ancestry is three fourths Indian and one-fourth Scotch, was the first person of dominantly Indian blood to graduate from Dartmouth since Charles Eastman, author of Indian Boyhood and other volumes, took his degree there in 1887 and David H. Markham in 1915. Frell, one of seven children, six of whom achieved college educations, was born on the reservation at Cherokee, North Carolina, in 1900 His grandfather had been a Baptist preacher on that same reservation. When Frell was a youngster the education of young Indians was still on a highly regimented basis. All children were required to attend and live at U. S. Government boarding schools even if their homes were only a mile away. They could not even go from class to class without being marched. They had to live, completely devoid of home life, in barracks-style dormitories. Frequently this pattern of enforced partial assimilation had the effect of disorienting the Indian, as he did not pick up the better qualities and characteristics of the white man while he lost appreciation of many of the traits of his own background. Frell's father, a blacksmith on the reservation, resolved that he was going to see his children do better than that.

So after six grades in a boarding school for Cherokees, Frell was sent to Virginia to Hampton Institute, the great Negro educational center, which then maintained a Federal Government-supported department for Indians. There Frell studied general agriculture, which pursuit was greatly to aid him in his subsequent Indian Service activities. Following Hampt on he studied two years at Phillips Andover with the partial aid of a scholarship from the Massachusetts Indian Association.

From Andover Frell came to Dartmouth in 1923, still with some aid from the Massachusetts Indian Association and with other help from the College. Further aid at Dartmouth came from waiting on tables in Commons in freshman year and working in the kitchen the remaining three years. Frell also worked as a gardener and chauffeur on a country estate during his summers. His major subject was. English.

Dartmouth, however, was not all work and studies for Frell who was there known as "Hoot." He became a member of Kappa Kappa Kappa. He made his letter in baseball, playing on the varsity team his last three years. He also played the tuba in the Community Symphony Orchestra those last three years and in the College Band for all four years. He was a member of Green Key and of Sphinx senior society.

With all his recognition, however, Frell confesses that at both Andover and Dartmouth he was occasionally tempted to give it all up and return to the reservation and his own people. It was not a matter of money, for he would not have been financially favored by doing so; it was an urge to be with other Indians and their customary ways and practices, a sort of homesickness.

FOLLOWING his Dartmouth graduation Frell was employed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs with Civil Service status. He was first sent as a teacher of seventh and eighth grade subjects to the Federal Indian Boarding School for Sioux children at Pierre, South Dakota. He remained there only two years but during that time he met a fellow teacher, Gladys Berry, partially of Indian lineage herself, whom three years later he married. While there, his parents then being deceased, he was adopted by a Sioux couple, Mr. and Mrs. Phillip Hawktrack, who thought that Frell, a Cherokee, resembled their own late son. When Mr. Hawktrack died he willed Frell his 160-acre farm. Tribal and Government rules, however, prevented him from ever assuming ownership.

Life in Pierre proved quite a shock to Frell. In Virginia and the Northeast, where he had spent about twelve years and where Indians were something of a curiosity, he had been the subject of considerable interest and respect. In the so-called Indian Country, however, he found Indians relegated to a much lower social position. Nevertheless, he did, in addition to singing bass with the School boys' glee club which he directed, play in the city band and play baseball with the Capital City Cowboys.

Then came Haskell Institute at Lawrence, Kansas, the largest Indian school in the United States, where he broadened out to teaching English, literature and public speaking to the high school seniors and had charge of the debating team. After six months at Haskell he went as a grammar school principal to the Federal Government's Hayward Boarding School at Hayward, Wisconsin, and there he and Miss Berry, who had transferred to Hayward, were married. Together they promoted hometown plays in which they participated.

In 1933 the Hayward Boarding School closed and Frell became a Government negotiator with school districts and boards in northern Wisconsin, attempting to have Indian pupils integrated into the regular public school systems. Although opposition on the ground of lack of facilities and race prejudice had to be overcome, Frell achieved considerable success. The Government itself had to construct a number of schools and then turn them over to the local school districts. The Government also had to purchase buses and even build roads to get the Indian children from the reservations to the schools. This represented a major change in the Government's previous long-established policy of always having the Indian children set apart in boarding schools. Frell thinks the change all to the good.

In 1936 came an assignment to the Lac du Flambeau Reservation for Chippewas in Wisconsin, which assignment was to last for nine years until 1945. The administration of this reservation, peopled by 800 Indians, performed all the functions normally carried on by an ordinary county government. Frell, as sub-agent, had charge of the school of 300 pupils, health and welfare activities, the probate of estates, law and order, construction and maintenance of the roads, protection of the forests, and the agricultural extension service. He organized a remarkable basketball league of eight teams. He managed the reservation baseball team, formed a band, arranged community parties, taught the children square dancing and arranged their general activities. He also served on the Board of the Wisconsin Mental Hygiene Society, represented both the Red Cross and the Selective Service Board on the reservation, served on the rationing and civil defense committees, and was in charge of all NYA, WPA and CCC activities on the reservation, on which was located a large Indian CCC camp. Because Frell preferred to remain among the people, he turned down two appointments to work in the Educational Division of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington.

IN 1945 Frell, promoted to the rank of full Superintendent, went to Fort Thompson, South Dakota, where he was in charge of two reservations of Sioux. A hospital and a boarding school were included. There he joined the Masons, sang in the men's chorus which he organized on one of the reservations and played the baritone in a band which he founded. There also he organized an Indian Fair.

In 1950 Frell became Superintendent of the Red Lake Reservation in Northern Minnesota where he remained until 1954. A staff of fifty persons helped him to supervise 3,100 Chippewas and to administer half a million acres of land. Reservation assets included a sawmill operated by the Indians and a commercial fishery producing each summer approximately a million and a half pounds of freshwater fish. After having served on the board and as a vice president of the Rotary Club of Bemidji, the neighboring town, he was elected president but was transferred away before he could assume the gavel. He would have been the first Indian president in that club's history. While at Red Lake, Frell organized an Indian Fair which consisted of a showing of agricultural products, arts and crafts and ceremonial dances. The first year it attracted visitors from 21 states. It continues as an annual institution.

In 1954 Frell was sent for the first time to the Far West, going to Idaho where he is now stationed. After six months as superintendent over four tribal groups in Northern Idaho, he was promoted and transferred to his present assignment as Superintendent of the Fort Hall Reservation.

Fort Hall is a reservation of 585,000 acres inhabited by about 2,600 people from two tribes, the Shoshones and the Bannocks. They have merged to a considerable extent but each started with a distinctive language. As both tongues are far from that of the Cherokees, Frell must speak to them in English. He is the second Indian-blooded superintendent to be in charge of this reservation, located near Pocatello in southeastern Idaho.

Administering the Fort Hall Reservation is a major job. All law and order enforcement is under Frell's supervision. Sheriffs do not enter the reservation, as state laws, generally speaking, have no force on a reservation. Only the FBI agents can enter and then only if a federal law has been violated. Tribal law, embodied in a code naming 33 offenses (which Frell remarks are not enough), covers most of the misdemeanors. A tribal court at the Fort Hall Reservation sets the penalties.

The Fort Hall Reservation includes a phosphate mine which brings in $50,000 net profits annually to the tribe. The Indians own 7,000 head of livestock. The irrigation project comprises 47,000 acres of irrigable land. All of it is owned by Indians but about 80% is leased to non-Indians. Frell regards this leasing practice as a detriment because it encourages the Indian to live off his rent money instead of scratching a living from the soil on his own. Some 200,000 acres of the reservation remain in tribal ownership; the remainder have been allotted to individual Indians. The Government serves as the trustee of Indian land.

The reservation administrative staff, composed of sixty persons, is made up of about 50% Indians who hold the custodial, maintenance and clerical jobs. The technical positions, such as soil scientists and technicians, are mostly in the hands of the whites. The Federal Government, as the Indians are its wards, must even undertake to see that proper medical care is given to a child with a hare-lip or a cleft palate. Frell's administration must further health clinics and other health activities. Potluck suppers and other morale-raising activities must be promoted. When the herds in the National Parks are reduced, Frell sometimes obtains supplies of buffalo and elk carcasses for his people. It is also up to him to allocate the range and to see to its management and development.

Adult education is a major activity to be encouraged, as about one-fourth of all the adult population of Fort Hall is still illiterate. At the educational meetings, attention to traditional ceremonials is encouraged. As for the youth, Frell had at the time of this interview five promising youngsters for whom he was trying to arrange scholarships anywhere in the United States.

Coordination of reservation activities with the United States Government, with which the Indians have 371 treaties, and the State and surrounding county governments is not the least of Frell's duties. One in his position must have a basic knowledge of Indian law which may be gained only through experience.

Mrs. Owl, who studied both at Bloomington State College in Illinois and at the University of Illinois, still substitutes as a teacher for Indians and has taken an interest in many of Frell's activities, in addition to bringing up their children. She has also helped to promote girls' clubs and 4-H Clubs. Although she participates in community activities, Frell reports that she does not care much for sports and, despite her partial Indian background, leaves the fly-fishing field to Frell who also occasionally indulges without her in bowling and indifferent golf. They both take a continued interest in religious activities. The products of their vegetable garden have won prizes at the Southeastern Idaho State Fair.

The Owls have two surviving children. Mary, aged 20, majors in home economics at the University of Idaho. She is accompanist for college musical groups and gives piano solos on their programs. Frela, aged 16, is named after her father and attends the Northfield School for Girls in Massachusetts. Mrs. Owl wrote me of Frell that "he is a wonderful husband and father. He taught the girls to handle a boat and to fish as soon as they could sit up. He always had time for them."

FRELL, as an Indian who has devoted his entire career to working among Indians, has very definite ideas as to the present and future of his people - especially those still, on the reservations.

The background of the Indian situation, he says, is that the original relation of the United States to the tribes was that of one nation to other nations, with the United States Senate having to ratify all treaties made with each tribe. Then in 1871 treatymaking with the Indian tribes ended and the making of agreements and laws was substituted. Now more than 5,000 laws on the subject of Indians have been enacted by Congress. There has developed over the years the concept that an Indian tribe is an independent domestic community under the exclusive guardianship and protection of a Federal Government responsible for all Indian affairs. The Indians have been conditioned to look to the Government for all services. The states and counties have maintained a laissez-faire policy in regard to the Indians, with the result that the Indian communities have remained isolated and apart from the main streams of American life.

The Indian children have only since 1928 had access to the public schools for other children. Because of the lack of a good educational system for Indians, very few of them have succeeded in securing college educations. The number of Indian-blooded teachers, nurses, doctors, lawyers and the like is negligible.

Frell greatly favors the integration of the Indian into general community life. He adds, however, that the Government has served as trustee for the Indian for more than 132 years and has developed in him a complete dependence, and that it would be tragic were this pattern of relationship suddenly to be terminated. The Indians cherish their present relationship with the United States Government. They feel that it owes them certain obligations by solemn treaty and that this relationship should not be terminated on any reservation until the Indian people on that reservation have been consulted and have given their consent by majority vote.

In the beginning the entire land acreage within the reservation was owned by the (tribe as a whole. In 1887 there was passed the Allotment Law allowing specific parcels of land to be given by deed to individual Indians. In some instances the land, upon the removal of Government restrictions upon it, became immediately subject to taxation. This taxation pressure and the Indians' desire for cash often caused Indians to sell their allotted land to nonIndians. So today some of the land on reservations where allotments took place is owned by whites.

Until the coming of the white man, intoxicating liquors were unknown to the Indians. The whites used them for barter and to facilitate the conquest of the tribes. In about the year 1802 Congress, at the request of the Indian chiefs, passed the Indian Liquor Law which made it a criminal offense to give or sell intoxicants to Indians or to introduce intoxicants within the Indian Country. This law, national in scope, continued in force until August 15, 1953, when it was repealed as part of the new policy of furthering integration.

Frell recalls that when he was stationed at the Lac du Flambeau Reservation in Wisconsin, a group of '27 men including Cug Daley and Cliff Randall visited him there. They invited him to accompany them to a local tavern for a highball. He still recalls their astonishment when he informed them that they would be subject to arrest should they purchase and offer him any alcoholic drink and, furthermore, that as he was the chief law enforcement officer of the area, he, although their guest, would have to be the one to arrest them. Frell's view is that the restrictive Indian Liquor Laws have done untold damage to the Indians, as they have served to discriminate against them and set them apart as second-rate citizens. It has given many of them inferiority complexes and has taught them to drink on the sly, often a whole bottle at a time, so as not to be caught.

FRELL gave to me in his own words the following summary of his views:

"The Indian tribal group is in a state of transition from tribal culture to the culture of the dominant race. The Indian has made progress reluctantly and slowly. He has resisted change. We must realize that in making the adjustment, the tribal group is giving up a culture. The Indian is discarding his Indian language and acquiring skill in English. His native religion has been disrupted and practically lost. Unfortunately, in many situations the white man's religion has not adequately replaced the Indian religion.

"Tribal government has broken down, but the Indian has been very slow to adopt the white man's form of government. The Federal Government has been dilatory in encouraging the Indian to adopt the new form of government. The result is that many of our tribal groups today have a very weak form of government.

"In the adjustment process the Indian has been forced to take on a new mode of making a living. He has had to learn to accept and hold a job - an activity completely foreign to him in his native culture. He has had to learn the value of time as the white man knows it. A very common expression on the Indian reservations is that meetings are held according to Indian time which means that the meeting is held whenever people assemble. The Indian has been slow to accept the white man's way of dress. On many reservations today there are men who wear their hair long, tied in braids. Indian women wear moccasins and shawls. The Indian problem is basically one of adjustment to a new way of life. There is no denying that the Indians face an acute cultural problem, the solution of which rests with the Indians themselves.

"If the Indian is to change his present situation, leadership must be developed within the group. There must be more evidence of desire for education. The children must complete high school and pursue courses in colleges and technical schools. Until more Indians are educated the Indian group will remain static. Teachers, nurses, ministers, farmers and businessmen must emerge from the group to assume the roles of leadership. This leadership is locally lacking among Indian groups. Initiative displayed by older Indians has been lost among the younger generations, in part due, perhaps, to the schooling system. It must be reacquired. It is my firm belief that the education of the Indian in the public school will eventually be the salvation of the Indian youth."

Frell, at my urging, showed me his personal file, in which are letters of appreciation from Senators, Governors, and other officials of the States in which he has served; and also photos, newspaper write-ups and accounts of farewell dinners, picnics and gifts from community groups to him and Mrs. Owl at the time he was transferred to new stations. Most impressive of all to me was an editorial from The Idaho Statesman of Boise following the 1955 State Conference on Indian Affairs of which Frell was chairman. The editorial ended: "A terrific battle is ahead for the Indians. Lucky for them, they have men of their own blood, such as Frell M. Owl, Superintendent of the Fort Hall Agency, to carry on the fight for them."

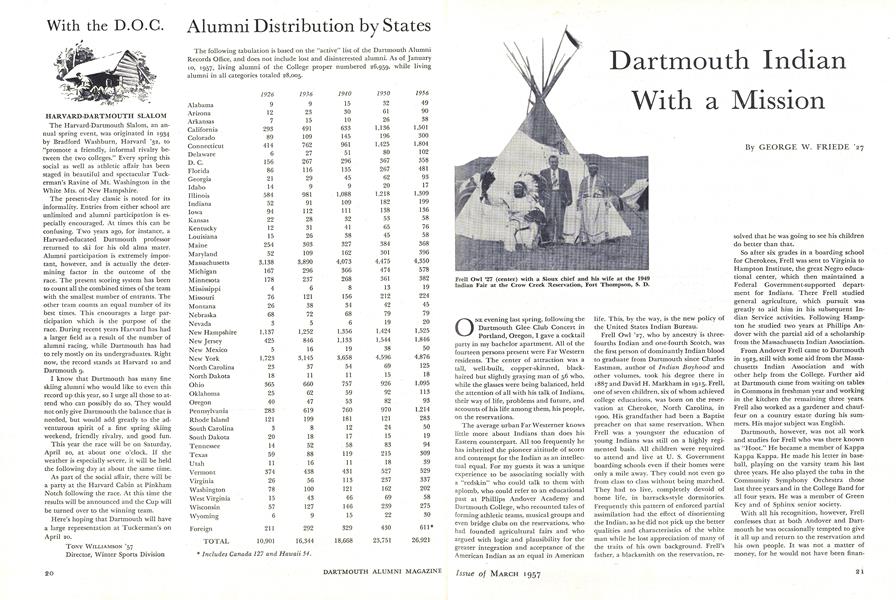

Frell Owl '27 (center) with a Sioux chief and his wife at the 1949 Indian Fair at the Crow Creek Reservation, Fort Thompson, S. D.

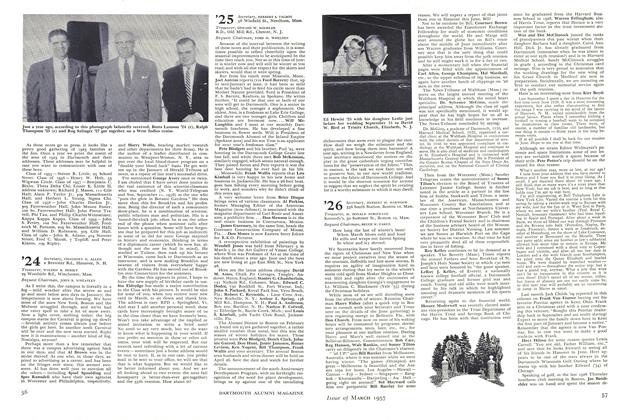

"Hoot" Owl (second from left, front row) with his baseball teammates in the spring of 1927.Left to right, front row: Murphy, Owl, Dey, Coach Tesreau, Michelini, Elliott. Second row:Gibson, Fusonie, Moran, Van Riper, Harris. Back row: Spaeth, Norris, Milliken, McLaughlin,Stevens, Carver.

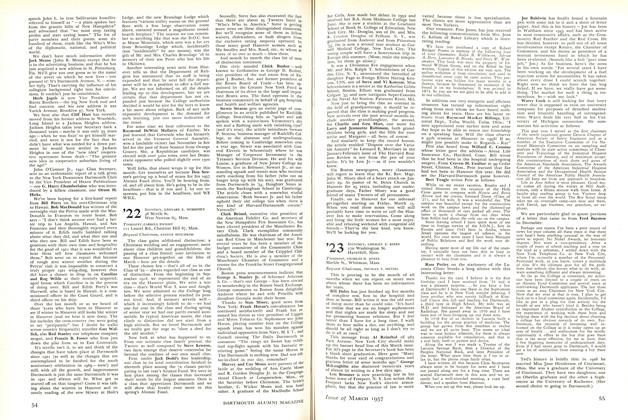

Frell Owl shown last May at the Bureau of Indian Affairs in Washington. L to r: E. J. Utz; Owl; Frank Parker, a Shoshone-Bannock Indian delegate from Fort Hall, Idaho; Glenn L. Emmons, Commissioner of Indian Alfairs; and Mrs. Teola Truchot, also an Indian delegate.

The other members oF the Owl family arewife Gladys and daughters Mary, 20, andFrela, 16, shown at Andover, Mass.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

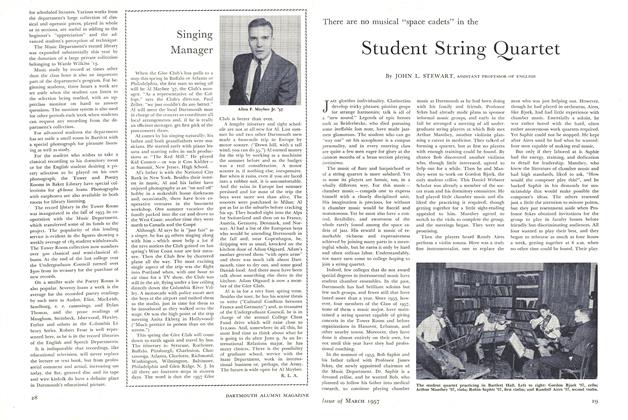

FeatureEducation the Groove

March 1957 By RAYMOND J. BUCK JR. '52 -

Feature

FeatureStudent String Quartet

March 1957 By JOHN L. STEWART -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1957 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

March 1957 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, BRUCE W. EAKEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923

March 1957 By CHESLEY T. BIXBY, CHARLES H. JONES, TRUMAN T. METZEL -

Class Notes

Class Notes1897

March 1957 By WILLIAM H. HAM, MORTON C. TUTTLE

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Frost's Shadow

SEPTEMBER 1997 By CLEOPATRA MATHIS -

Feature

FeatureA Delicate Balance

November 1975 By DAN NELSON -

Cover Story

Cover StoryGILLIAN APPS '06

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Cover Story

Cover Story"Are the fireflies ghosts?"

OCTOBER 1985 By Priscilla Sears -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth Dogs

OCTOBER 1997 By Robert Nutt '49