1625-1660. By Wilcomb E.Washburn '48. Williamsburg: Virginia350th Anniversary Celebration Corporation,1957. 64 pp. $0.50.

For the occasion of the 350th anniversary of the Jamestown settlement, a distinguished committee on publications has sponsored a series of 23 popular monographs dealing with various aspects of seventeenth-century Virginia history. Although designed apparently for the general reader - perhaps primarily for the Jamestown visitor this year - these booklets, if Mr. Washburn's mapped and illustrated monograph is a representative sample, offer substantial fare.

Mr. Washburn, an instructor in history at William and Mary College and Research Associate at the Institute of Early American History and Culture in Williamsburg, begins his account with a crucial transition in Virginia history, the year in which the London Company lost its charter. With the colony subsequently under the direct, and loosened, control of Charles I, its character changed permanently. In effect, Mr. Washburn suggests, only investors had been able to control producers; the revocation of the Company charter released local forces which were to affect the entire course of Virginia, and thus Southern, and thus American, history.

The rapid shifts and realignments among governing figures and in governing policies, the jealousies and squabbles growing out of the greed for individual gain form the factual bases of his account, and Mr. Washburn offers intelligent suggestions toward reappraisal. He suggests, for example, that royal governors such as Harvey and Berkeley have been much maligned by historians who have seen each colonial challenge to royal authority as a contribution to "democracy"; very often, he notes, their challengers were prominent councillors whose behavior was governed chiefly by motives of the purest self-interest. To order the chaos of a swiftly-moving situation, Mr. Washburn seizes upon the continuing features of the infant colony: its increasing population and the abundant land easily wrested from the Indians. Probably what, more than anything else, set the enduring pattern of Virginia's centrifugal political forces was space: not only the rich lands lying open to the south and west, but also, ironically, where space became time, the sea to the east which loosened or severed the ties to England. In the long run, the royal governors, for all practical purposes cut off from their source of authority, were forced to bow again and again to the land barons of the New World. In miniature the economic reordering suggested here foreshadows the redirection of American history by the giant lunges of industry and finance following the Civil War.

The brief bibliographical essay on authorities which closes the booklet indicates the serious level of approach; Mr. Washburn's work is not mere romance for the idle tourist, despite its occasion, its size, or its price.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

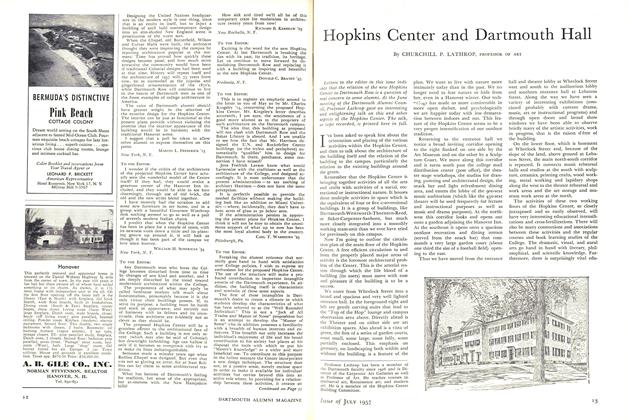

FeatureHopkins Center and Dartmouth Hall

July 1957 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Feature

FeatureThe Commencement Address

July 1957 By DOUGLAS HORTON, D.D. '57 -

Feature

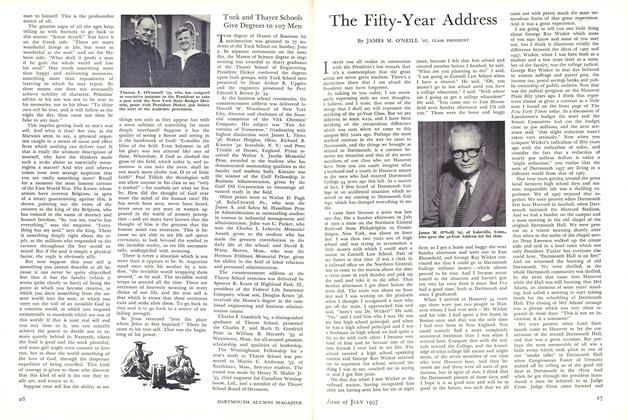

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1957 By JAMES M. O'NEILL '07 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1957 By LLOYD L. WEINREB '57 -

Feature

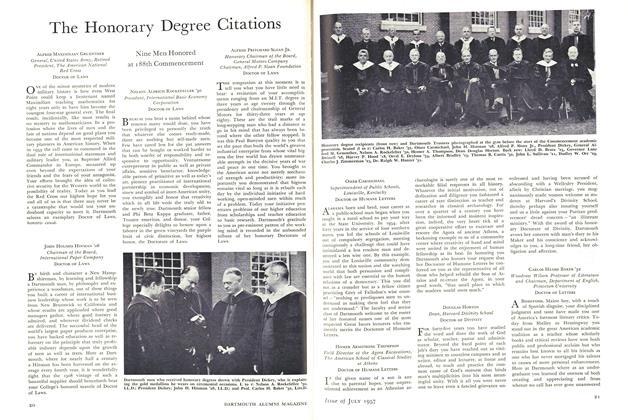

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1957 -

Feature

FeatureThe 1957 Commencement

July 1957 By GEORGE O'CONNELL

Books

-

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

JULY 1970 -

Books

BooksTHE NORTHWEST FUR TRADE

November 1928 By A. H. B. -

Books

BooksCOMPLETE CREDIT AND COLLECTION LETTER BOOK.

June 1954 By JOHN A. GRISWOLD -

Books

BooksTHE MYSTERY OF "A PUBLIC MAN,"

March 1949 By Merle Curti. -

Books

BooksNO LAMB FOR SLAUGHTER.

JUNE 1963 By RICHARD MORIN '24 -

Books

BooksTWELVE AGAINST THE GODS

MARCH 1930 By Robert P. Lane