THE 31-inch snowfall in the middle of February brought me a fine case of American grippe which laid me low for a week. During the first few days I did not care much about reading, or anything else. However, one day there arrived, from Doubleday, Nathan F. Leopold's fascinating story, Life Plus 99 Years, with a most constructive introduction by Erie Stanley Gardner. As I read I completely forgot my own physical weakness and lost myself in the life of a man who had already served 33 years in jail.

The crime of Loeb and Leopold was a terrible thing. It was labeled the crime of the century. The press ran riot. Today it would make the headlines for a day and then be forgotten, for, since 1924, horrible crimes by teen-agers have become commonplace. Even the Lincoln, Nebraska, boy will soon be forgotten and he killed eleven innocent people without rhyme or reason. Still, in the public mind the crime against Bobbie Franks was, and is, the crime never to be forgotten. This has been tough on Leopold.

After reading his book I am one who thinks that he has long expiated his crime. In fact, the day I finished the book I read in the paper that he had been or was to be released on parole. He deserves this and I am certain he will make good, now given his chance.

My nearest experience with the kind of life he describes was a hitch in the regular army forty years ago. The same dreadful monotony; the same horrible smells; the same drab food; the same stupidity. Even the same type of companion, as many of my "buddies" had been in stir, and would undoubtedly be again. Some of them nice, dignified guys, with a code of their own. "Prison ethics indeed," the ignorant will snort, but they will be wrong. Prison and army codes are as conventional and rigid as a tribal initiation.

How an intelligent young man made the most of a harrowing life is clearly delineated. He did despair. He thought often of suicide. He became sincere and devout. He prayed. He has all the remorse anyone could have for a horrible slip made in his dim past. He has gone on with his education with courses from Columbia, lowa State, and Michigan. He learned languages, even Braille. He set up and introduced new methods in the Prison Library at Statesville. He has been a great success as a teacher. He has, in fact, become a better citizen than many on "the outside."

His book, unlike Caryll Chessman's of San Quentin, is written unsensationally. The style is that of a first-class thesis in sociology. It is sober, matter of fact, and carries with it an air of sincerity and rectitude. But it is exciting reading for all that. This is the way prisons really are.

Dave Camerer '37 has written a novel about war in the air in Italy. Ploesti was the haunted name. What is especially fine in the book is the description of the daily life of men driven by their own codes to impossible assignments, not once but time after time. Sooner or later death was sure to hit the men who made the Ploesti run. The 15th Air Force, in which the author served, did the job. Already its methods are as obsolete as the Civil War mortars used in American coast defenses in 1918. But the memory of their everyday heroism remains. I have not forgotten the men of the Classes of 1941 and 1942 here at Dartmouth who measured up.

Camerer's book deserves a wide reading and I hope many alumni will buy and read The Damned Wear Wings.

A little comic relief will be found in the late Oliver St. John Gogarty's A WeekEnd in the Middle of the Week (Doubleday). Urbane and witty essays by the man who walked, more than once, down Sackville Street, even as you and I.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAMERICAN HIGHER EDUCATION 1958

April 1958 -

Feature

FeatureIt's Spring and Job Time for Seniors

April 1958 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureCollege Plans April Music Festival

April 1958 -

Feature

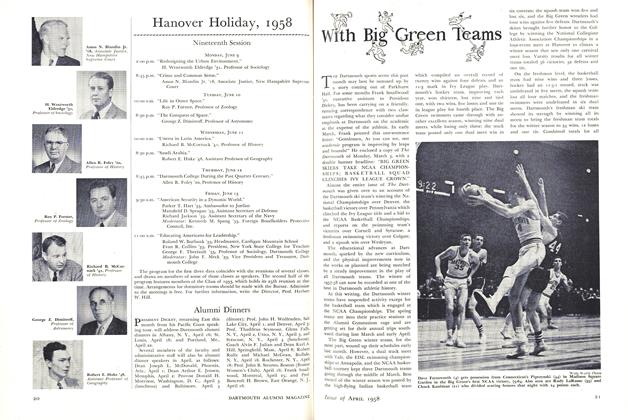

FeatureHanover Holiday, 1958

April 1958 -

Class Notes

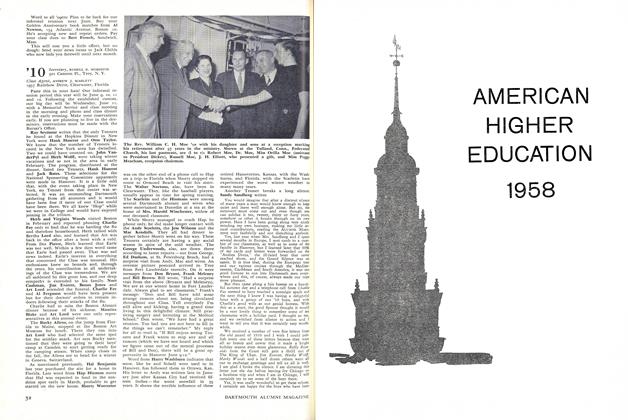

Class Notes1918

April 1958 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, RICHARD A. HOLTON -

Class Notes

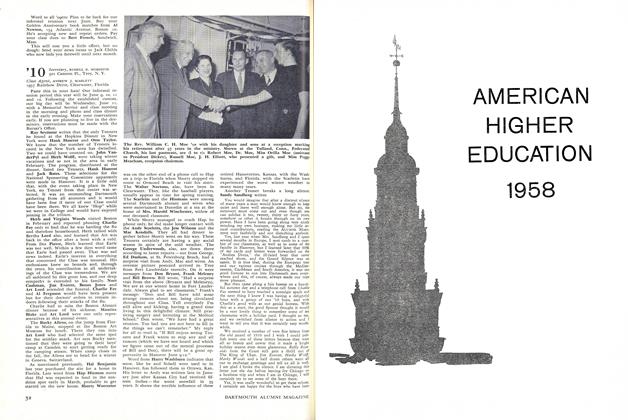

Class Notes1910

April 1958 By RUSSELL D. MEREDITH, ANDREW J. SCARLETT

HERBERT F. WEST '22

-

Article

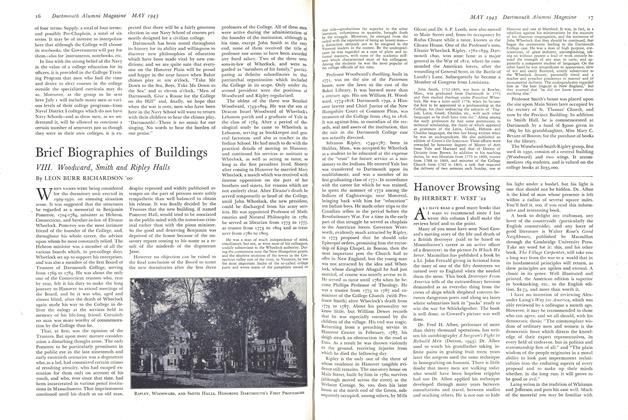

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1941 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1943 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

May 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE MAKERS OF AMERICA AND THEIR LAND OF PROMISE.

November 1952 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1955 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE IVY LEAGUE TODAY.

December 1961 By HERBERT F. WEST '22