BROUGHT to light after many years of obscurity, the incredible story of Dr. Albert Cushing Crehore, who had taught at Dartmouth from 1893 to 1900 as Appleton Assistant Professor of Physics, flickered quietly to its conclusion in a Cleveland hospital one day last January. Dr. Crehore, hailed as the most brilliant electrical engineer in the country at the turn of the century, died as he had lived, alone and unrecognized, a controversial figure whose atomic theories and systems for measuring the speeds of projectiles waited forty years for acceptance.

Dr. Crehore was descended from one of the most prominent families of the Western Reserve. His great-grandfather settled the town of Painesville, Ohio, in 1811, and his mother, Lucy Williams, married Prof. John D. Crehore, Class of 1854, who surveyed part of Cleveland and taught at Washington University. Other members of his family were scientists, surgeons and businessmen of great distinction.

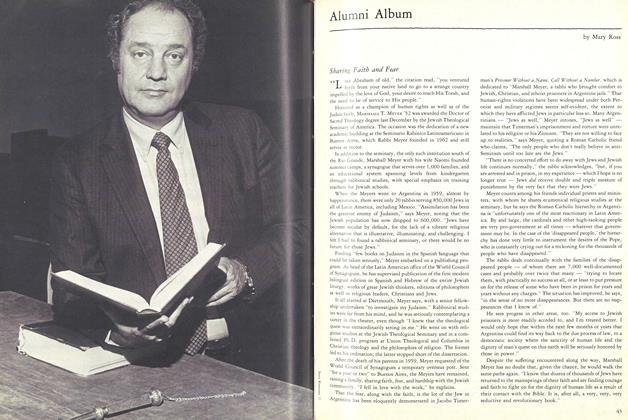

Albert Crehore graduated from Yale, studied engineering at Johns Hopkins, and later took his doctorate in physics at Cornell. He began his career when the science of electricity was in its infancy, and the star of his genius blazed a bright path across the sky in its development. In 1893 he came to Dartmouth and built an apparatus, then considered "fantastic," for measuring the speed of projectiles. Later he turned to the study of alternating currents and worked on transmission through oceanic cables, which he speeded up 25%. A company was formed to exploit his inventions and he went into partnership with two men, one of whom was George O. Squier, Sc.D. '22, who was sent by the government to study with Crehore and who later became a major general and chief of the U.S. Signal Corps. But through bad luck and poor management the company started a long decline that ended eventually in bankruptcy. Crehore came up with new and valuable inventions which were sold to AT&T, but all the money went into his sagging company. He soon became penniless and a few years later a second tragedy struck when his marriage ended in divorce.

It was at this point that Albert Crehore, alone and unheeded, vanished from the sight of the world for 30 years. Ironically though, it was to be during this period that his revolutionary theories and ideas, generally scoffed at earlier, began to gain recognition and were "rediscovered" by others. He had spent many years fitting Newton's laws of gravitation into the atom, and he had proved that two hydrogen atoms reach an equilibrium near the "universal distance" which is close to onehundred millionth of a centimeter. He was said to have been the first man to explore the breaking of a circuit at the zero point in alternating current; and he also had proved a very important constant in physics, that the dimensions of specific inductive capacity and magnetic permeability are each the same as, and equal to, the reciprocal of a velocity. A man far ahead of his time, Dr. Crehore had discovered laws that were to be the basis of much of the rapid expansion of physics and electricity in the later years of the century.

In 1939 a Cleveland newspaper reporter discovered the old man, living by himself in a shack like a hermit, forgotten by the world. He was induced to resume the work he had left many years before and was given a small laboratory in General Electric's Nela Park science city. There until his death last January, Dr. Crehore, much aged but his mind still brilliantly active, worked on a secret intercontinental ballistic missiles project for the Pentagon, applying in 1959 his theories that the world had ignored forty years before.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureReport on Trustee Organization

October 1959 -

Feature

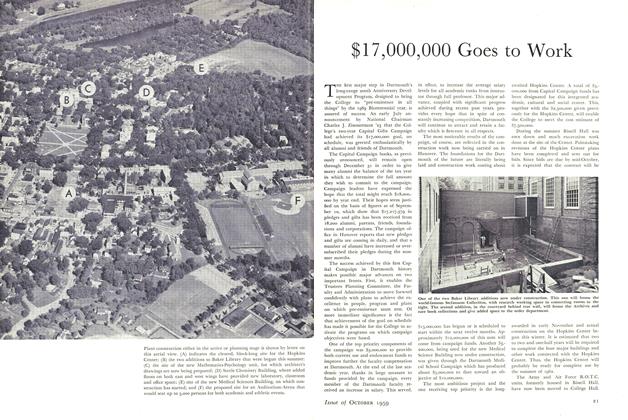

Feature$17,000,000 Goes to Work

October 1959 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

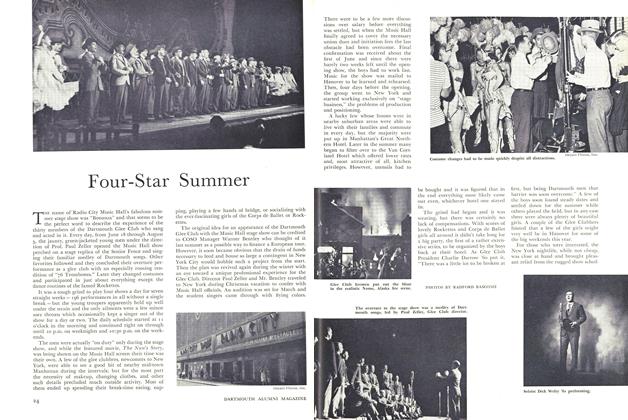

FeatureFour-Star Summer

October 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Article

ArticleEducation: Creator of Centennials

October 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1959 -

Article

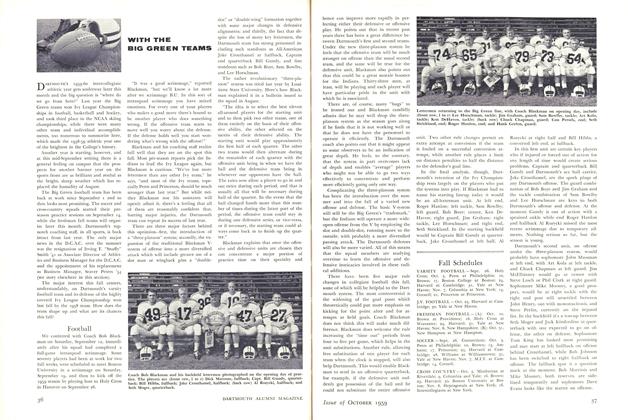

ArticleFootball

October 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45