Following is the text of the address delivered by President Dickey at Titusville,Paon August 26, 1959, at the exercisesmarking the Centennial of Oil.

MAN is a knowing animal. In an individual life he is permitted to know for himself only an incredibly small moment of that seemingly endless mystery we so easily and trustingly call "time." This, of course, is true of all creatures, but man seems to be the only creature that has presumed to know something about things past as well as knowing that most mortal moment, the present. Thus it is that man alone celebrates centennials and thus it is that human society has its enterprises of knowing: our schools and colleges, as well as its enterprises of industry. The anniversary we celebrate here today is a dramatic witness to both the growth of man's knowledge and the growing oneness of man's knowledge and of his doing in all directions.

A centennial is not merely a hundred years of yesterdays. It is one of those somewhat arbitrary counting points in our arithmetic that provides a convenient place for marking a moment in the past that we now, on looking back, are permitted to know was extraordinary and, in this instance, was great with significance for the future.

It does not dull the edge of our keen enjoyment of this centennial of the oil industry to recall that we live in a period and in a land where almost every day is an anniversary. Indeed, it adds to the meaning of this celebration to be mindful that centennials of such significance are relatively new features in the span of man's history and that there are still vast areas on earth where such opportunities for the celebration of the past's achievements are still largely in the hoped-for future.

The truth is that the vast majority of man's yesterdays are unmarked with identifiable significance. And, before we become too self-satisfied with ourselves and our anniversaries, let us remember that we are gathered to honor what was achieved here in 1859 and that the significance of 1959 is still to be proven.

While we are making the most of our acquired capacity for being humble, it might be well to remark that the beginnings of the oil industry reach back a few years beyond 1859. I am not at the moment alluding to the pioneering research done on rock oil at Yale and Dartmouth in 1855 and 1853 respectively, nor am I referring to the use made of bitumen some 4,000 years ago in the city of Ur on the Persian Gulf or even to the account in Genesis of the directions given Noah by the Lord for making the ark watertight with pitch. No, I simply suggest that in all our celebrating of man's cleverness we not overlook the fact that long before man discovered it, perhaps as much as 450 million years before this greatest of all treasure hunts got under way, somehow petroleum was produced and hidden where simians could find it out when at long last they came along with their busy hands and curious minds.

Oil and simians have the natural affinity of the hidden and of the hunters who, in Robert Frost's phrase, "would have the rabbit out of hiding." And I suggest to you that there may be even more to the relationship of man and oil than the simian propensity for uncovering hidden things.

I remind you that 1859 is famous not only in Titusville; it is also a landmark in man's understanding of himself. The same year that Colonel Drake drilled his well Charles Darwin published his momentous book, Origin of Species. I venture to mention this other competitive centennial not to avoid a charge under the anti-trust laws that the oil industry has a monopoly on the year 1859, but because I think it is entirely possible, indeed probable, that these two seemingly totally unrelated happenings in 1859 in fact combined to produce an impact on the future that standing alone neither would have caused.

It is commonplace knowledge today that petroleum has played a major part, both literally and figuratively, in firing the scientific and technological advances of the past hundred years. Paradoxically two world wars also played a part in pacing the advance of science and technology in the first half of the 20th Century, and yet even as to wars a case can be made that conflicts of world-wide scope were themselves creatures of the power and mobility of the age of petroleum.

Darwin's part in all this was less direct and even if in his own particular field he. is no longer credited with being as much of an intellectual pioneer as at first seemed so, the fact is that Darwin and the views attributed to him concerning the evolution of life and man's origin became the battleground over which perhaps the last great public controversy between science and religion was fought out. If today we sometimes wonder what the "shooting was all about," nevertheless we must say, must we not, that some such controversy was probably necessary to make the public as a whole aware of the fundamental place of science in contemporary life. In turn, can there be any great doubt that without such general awareness and acceptance of science in a community and perforce in the community's educational enterprises that petroleum's full power and potential as we know it today would still remain largely locked behind bars of ignorance and indifference?

The drillers of the Drake Well and the author of Origin of Species probably had little or nothing in common personally beyond exceptional determination to have their respective "rabbits" out of hiding. But today as we look back upon these two momentous events that took place in 1859 we can now see that these seemingly utterly dissimilar achievements were built upon the common foundation of prior intellectual pioneering. It is fitting that as we honor Colonel Drake, the first driller of oil, we should also acknowledge the pioneering intellectual work that began the most important oil discovery of all, the discovery of oil's nature. It was on this discovery that Drake's rig and all the rigs that followed rested.

THE story of the studies at Dartmouth and Yale that led to the drilling of the Drake Well has been frequently told in recent years. It is a fascinating story and bears much retelling, but I think the most important item for us in that story today is the fact that the centennials of those studies preceded this one by six and four years respectively. Man first had to know something of the nature of oil before the hard and ingenious enterprise of drilling for it occurred to him and seemed worth the effort.

In 1853 Dr. Francis B. Brewer of Titusville, a graduate of Dartmouth College, brought a sample of Pennsylvania rock oil to Dartmouth for examination by his uncle, Dr. Dixi Crosby, a teacher in the Dartmouth Medical School, and Oliver P. Hubbard, professor of chemistry. We have no record of the tests used by Professors Crosby and Hubbard in their analysis, although there is little doubt from our knowledge of the meager equipment available to them that by today's standards this first scientific examination of crude oil would be judged elementary. But that is not the point; the point is that this was the first effort to use the ways of science to create reliable knowledge of petroleum and that from that effort and its positive outcome came the interest and conviction of George H. Bissell, another Dartmouth graduate and friend of Dr. Crosby, that in turn led to further scientific studies and the drilling achievement we celebrate here today. It was in 1855 at Bissell's instigation that Professor Benjamin Silliman Jr., a distinguished Yale scientist, conducted detailed experiments that led to the publication by him in April 1855 of a study on the nature of petroleum that has been termed the "birth certificate" of the oil industry. "Birth certificate" or a prospectus for a promising marriage, Silliman's remarkable report was assuredly procured and used by Bissell and his partner, Jonathan G. Eveleth, to convince prospective investors of the scientific legitimacy of the future of rock oil and their plans to drill for it.

We are told that Professor Silliman charged Bissell's group $526.08 for his report. Dartmouth's charge is still being computed.

Men draw different morals from such a story depending upon their point of vantage or disadvantage. Certain it is, however, that this opening chapter and its fantastic sequel in the unfolding story of oil during the past hundred years leave no room for doubt that knowledge and enterprise beget each other. This is a truth that is well known today in both education and industry. Perhaps we should limit that statement a bit by saying that education and industry have readily and, indeed, inevitably found common ground, if not common cause, in most fields of research. To be sure, there are still differences of emphasis and aim between much academic and industrial research and there is an acute need throughout our society for more basic searching for new knowledge. But broadly viewed, we can say today that research, at least in the natural sciences, is a respectable activity and even a fashionable investment in the eyes of most Americans.

I suggest to you, however, that we are not nearly so clear and of one persuasion in our understanding of how you go about producing the research we need and seem relatively willing to purchase. Many businessmen, although not I think many acknowledged business leaders, rather naturally still regard research as a commodity to be purchased when and as needed rather than as something that must be home grown, so to speak, in the form of better educated individuals throughout the American community.

The point is nicely made by the story about the huge multi-million-dollar plant built by the Government during World War II for producing uranium 235 for our first A-bombs. One day after the mysterious new plant had been operating for a year or so, one of the curious-minded natives of the locality asked an official of the plant how it was that nothing ever seemed to be shipped out of the plant although it regularly received trainload after trainload of raw ore material. The official replied that the finished product of the plant was exceedingly small in bulk and indeed might be sent out in thimble-full quantities. Our curiousminded friend pondered this reply for awhile and then knowingly remarked that if this was so, it seemed to him that it might be smarter for the Government just to buy the stuff. And so it often seems with knowledge, that there must be a cheaper way to get the stuff than to maintain our vast educational system of schools and colleges with their constant need for more and more money. But always the answer ultimately comes back: knowledge is not to be bought, it has to be created man by man.

Today, as in the case of rock oil at Dartmouth and Yale some hundred years ago, the men are available to do intellectual pioneering only -if years before they have been adequately educated for such work in our schools and colleges. The society that educated Brewer, Crosby, Hubbard, Bissell and Silliman never dreamed that it was there - by preparing the way for the coming of the petroleum age, but educate them it did and they did the rest. And so it is with us; we cannot buy knowledge except as yesterday we bought education.

We who occupy that moment called "the present" can celebrate but we do not create today's centennials; their creation was the work of yesterday's education. The centennials of the future will tell our story. May it be as good as that which we are privileged to honor here today.

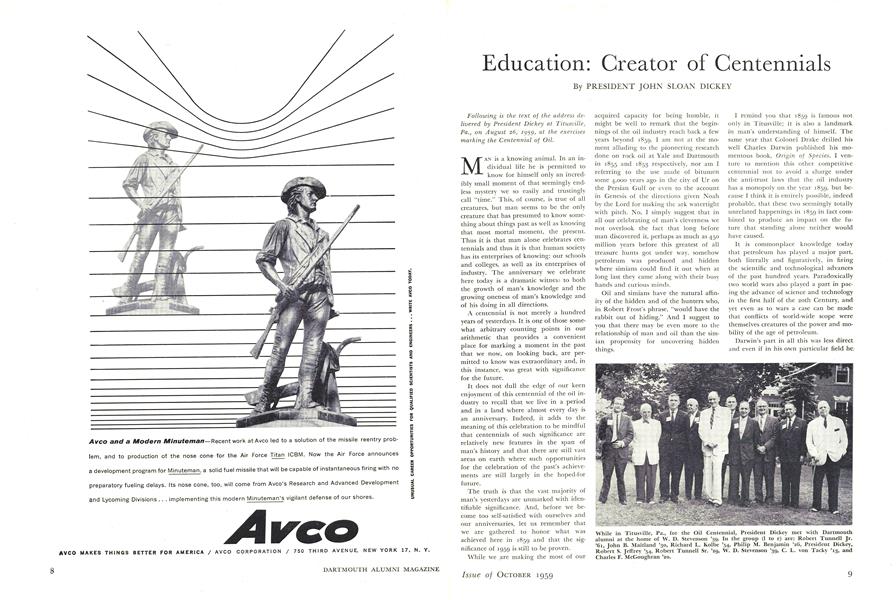

While in Titusville, Pa., for the Oil Centennial, President Dickey met with Dartmouth alumni at the home of W. D. Stevenson '39. In the group (l to r) are: Robert Tunnell Jr. '61, John B. Maitland '30, Richard L. Kolbe '54, Philip M. Benjamin '26, President Dickey, Robert S. Jeffrey '54, Robert Tunnell Sr. '29, W. D. Stevenson '39, C. L. von Tacky '13, and Charles F. McGoughran '20.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureReport on Trustee Organization

October 1959 -

Feature

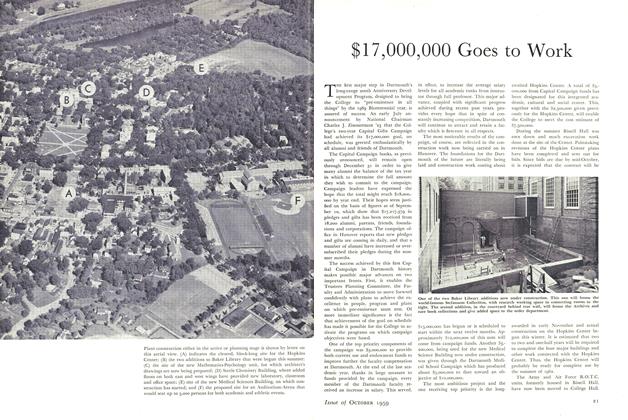

Feature$17,000,000 Goes to Work

October 1959 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

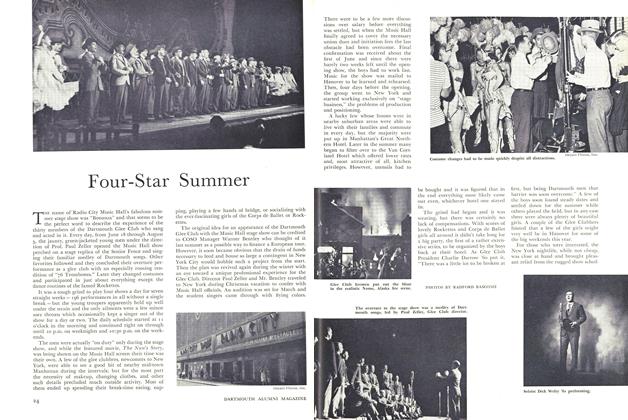

FeatureFour-Star Summer

October 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

October 1959 -

Article

ArticleFootball

October 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1933

October 1959 By WESLEY H. BEATTIE, GEORGE N. FARRAND

PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY

-

Article

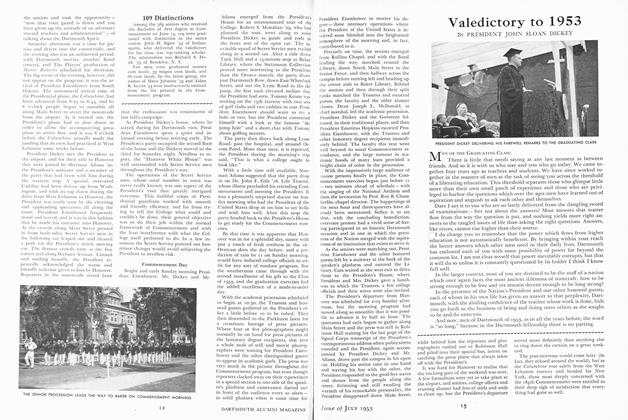

ArticleValedictory to 1953

July 1953 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Article

ArticleValedictory to 1959

JULY 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Article

ArticleA Sort of Pride

October 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

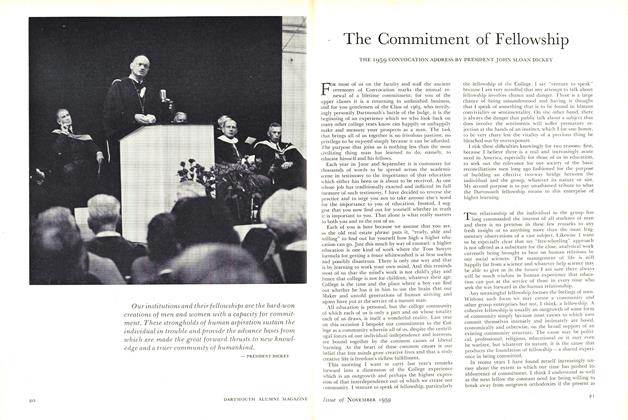

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1961

July 1961 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureValedictory to 1968

JULY 1968 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY

Article

-

Article

ArticleWSSF Nets $3,179

June 1946 -

Article

ArticleGreat Issues

October 1948 -

Article

ArticleCenter Plans Praised

July 1957 By JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR. -

Article

ArticleAnd the Livin' Is Easy

SEPT. 1977 By MARK HANSEN '78 -

Article

ArticleLeland Griggs, Naturalist

October 1940 By PARKER MERROW '25 -

Article

ArticleAFTER THE WALL

SEPTEMBER 1991 By Professor Konrad Kenkel