History and Bibliographythrough colonial times. By Ray Nash. Boston: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 1959. 77 pp., 36 collotype plates. $10.00.

What hands our American forebears wrote, what sort of men taught them handwriting and what importance was attached to writing in this country before 1800 are described in this book in which Professor Nash has gathered part of the harvest of inquiries pursued mostly during his years of teaching at Dartmouth in the late thirties and the forties and fifties.

More than a scholar's book written for other scholars, American Writing Mastersand Copybooks opens some unexpected and engrossing views of early Americans and America. The layman interested in American history will find an excellent historical essay and abundant illustrations. Of equal interest to the scholar is a bibliography which "aims to describe every edition and variant of all American publications on handwriting by authors working before the end of the eighteenth century."

Starting with a brief description of the background of handwriting styles which influenced the writing of early comers to these coasts, Professor Nash traces handwriting fashions and standards in this country to 1800. Humor and human details gleam in his comments on the handwriting of the founders of the colonies and the republic.

He marks the middle of the eighteenth century as high point in the colonial development of the American writing master. His portraits of two men then teaching writing, Abiah Holbrook of Boston and Richard Rogers of Oxford near Worcester in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, are particularly interesting. So are his comments on Benjamin Franklin and the earliest printed instructions to writers in America, published by Franklin and Hall in 1748 in The American Instructor: or, Young Man's Best Companion.

Another portrait carries the reader into the story of the decline of the American writing master. John Jenkins, whose activity is most evident between 1790 and 1820, is credited by Professor Nash with development of "the most substantial and original native contribution" to the literature of instruction in handwriting. But Jenkins's claim that people could learn from his system not only how to write well themselves but also how to teach others had sorry results. "... Jenkins had only himself to thank for opening the gates to a crowd of self-anointed professors of penmanship."

The excitement of discovering some remarkable details of the lives of these American writing masters belongs to the reader as well as the author.

The book is handsomely printed. Its reference value is enhanced by an excellent index spaciously arranged by the printer for easy reading.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Books

-

Books

BooksNEW VALUES IN MUSIC APPRECIATION

February 1936 By D.E. Cobletgh -

Books

BooksDARTMOUTH SONG BOOK

April 1950 By JUD LYON '4O -

Books

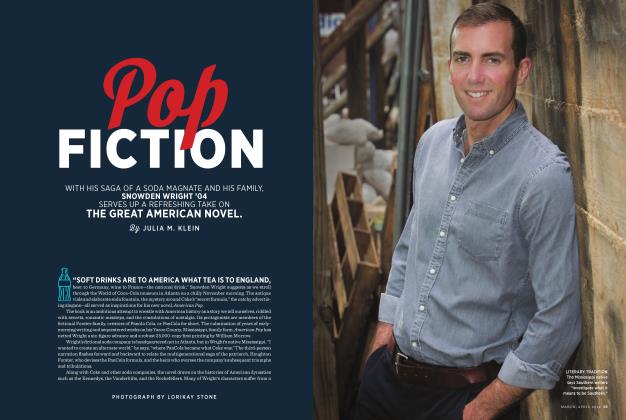

BooksPop Fiction

MARCH|APRIL 2019 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Books

BooksTHE HUMANITIES TODAY.

MAY 1970 By NEIL OXENHANDLER -

Books

BooksGRAY MATTERS, A NOVEL.

FEBRUARY 1972 By ROBERT H. ROSS '38 -

Books

BooksAmerican Parties and Politics

JANUARY, 1928 By W. R. W.