Most teachers teach because they love their jobs. But low pay forcing many to leave the profession,

EVERY TUESDAY EVENING for the past three and a half months, the principal activity of a 34-year-old associate professor of chemistry at a first-rate midwestern college has centered around Section 3 of the previous Sunday's New York Times. The Times, which arrives at his office in Tuesday afternoon's mail delivery, customarily devotes page after page of Section 3 to large help-wanted ads, most of them directed at scientists and engineers. The associate professor, a Ph.D., is job-hunting.

"There's certainly no secret about it," he told a recent visitor. "At least two others in the department are looking, too. We'd all give a lot to be able to stay in teaching; that's what we're trained for, that's what we like. But we simply can't swing it financially."

"I'm up against it this spring," says the chairman of the physics department at an eastern college for women. "Within the past two weeks two of my people, one an associate and one an assistant professor, turned in their resignations, effective in June. Both are leaving the field - one for a job in industry, the other for government work. I've got strings out, all over the country, but so far I've found no suitable replacements. We've always prided ourselves on having Ph.D.'s in these jobs, but it looks as if that's one resolution we'll have to break in 1959-60."

"We're a long way from being able to compete with industry when young people put teaching and industry on the scales," says Vice Chancellor Vern O. Knudsen of UCLA. "Salary is the real rub, of course. Ph.D.'s in physics here in Los Angeles are getting $8-12,000 in industry without any experience, while about all we can offer them is $5,500. Things are not much better in the chemistry department."

One young Ph.D. candidate sums it up thus: "We want to teach and we want to do basic research, but industry offers us twice the salary we can get as teachers. We talk it over with our wives, but it's pretty hard to turn down $10,000 to work for less than half that amount."

"That woman you saw leaving my office: she's one of our most brilliant young teachers, and she was ready to leave us," said a women's college dean recently. "I persuaded her to postpone her decision for a couple of months, until the results of the alumnae fund drive are in. We're going to use that money entirely for raising salaries, this year. If it goes over the top, we'll be able to hold some of our best people. If it falls short... I'm on the phone every morning, talking to the fund chairman, counting those dollars, and praying."

THE DIMENSIONS of the teacher-salary problem in the United States and Canada are enormous. It has reached a point of crisis in public institutions and in private institutions, in richly endowed institutions as well as in poorer ones. It exists even in Catholic colleges and universities, where, as student populations grow, more and more laymen must be found in order to supplement the limited number of clerics available for teaching posts.

"In a generation," says Seymour E. Harris, the distinguished Harvard economist, "the college professor has lost 50 per cent in economic status as compared to the average American. His real income has declined substantially, while that of the average American has risen by 70-80 per cent."

Figures assembled by the American Association of University Professors show how seriously the college teacher's economic standing has deteriorated. Since 1939, according to the AAUP's latest study (published in 1958), the purchasing power of lawyers rose 34 per cent, that of dentists 54 per cent, and that of doctors 98 per cent. But at the five state universities surveyed by the AAUP, the purchasing power of teachers in all ranks rose only 9 per cent. And at twenty-eight privately controlled institutions, the purchasing power of teachers' salaries dropped by 8.5 per cent. While nearly everybody else in the country was gaining ground spectacularly, teachers were losing it.

The AAUP's sample, it should be noted, is not representative of all colleges and universities in the United States and Canada. The institutions it contains are, as the AAUP says, "among the better colleges and universities in the country in salary matters." For America as a whole, the situation is even worse.

The National Education Association, which studied the salaries paid in the 1957-58 academic year by more than three quarters of the nation's degree-granting institutions and by nearly two thirds of the junior colleges, found that half of all college and university teachers earned less than $6,015 per year. College instructors earned a median salary of only $4,562—not much better than the median salary of teachers in public elementary schools, whose economic plight is well known.

The implications of such statistics are plain.

"Higher salaries," says Robert Lekachman, professor of economics at Barnard College, "would make teaching a reasonable alternative for the bright young lawyer, the bright young doctor. Any ill-paid occupation becomes something of a refuge for the ill-trained, the lazy, and the incompetent. If the scale of salaries isn't improved, the quality of teaching won't improve; it will worsen. Unless Americans are willing to pay more for higher education, they will have to be satisfied with an inferior product."

Says President Margaret Clapp of Wellesley College, which is devoting all of its fund-raising efforts to accumulating enough money ($l5 million) to strengthen faculty salaries: "Since the war, in an effort to keep alive the profession, discussion in America of teachers' salaries has necessarily centered on the minimums paid. But insofar as money is a factor in decision, wherever minimums only are stressed, the appeal is to the underprivileged and the timid; able and ambitious youths are not likely to listen."

WHAT IS THE ANSWER?

It appears certain that if college teaching is to attract and hold top-grade men and women, a drastic step must be taken: salaries must be doubled within five to ten years.

There is nothing extravagant about such a proposal; indeed, it may dangerously understate the need. The current situation is so serious that even doubling his salary would not enable the college teacher to regain his former status in the American economy.

Professor Harris of Harvard figures it this way:

For every $100 he earned in 1930, the college faculty member earned only $B5, in terms of 1930 dollars, in 1957. By contrast, the average American got $175 in 1957 for every $100o he earned in 1930. Even if the professor's salary is doubled in ten years, he will get only a $70 increase in buying power over 1930. By contrast, the average American is expected to have $127 more buying power at the end of the same period.

In this respect, Professor Harris notes, doubling faculty salaries is a modest program. "But in another sense," he says, "the proposed rise seems large indeed. None of the authorities ... has told us where the money is coming from." It seems quite clear that a fundamental change in public attitudes toward faculty salaries will be necessary before significant progress can be made.

FUNDING THE MONEY is a problem with which each college must wrestle today without cease.

For some, it is a matter of convincing taxpayers and state legislators that appropriating money for faculty salaries is even more important than appropriating money for campus buildings. (Curiously, buildings are usually easier to "sell" than pay raises, despite the seemingly obvious fact that no one was ever educated by a pile of bricks.)

For others, it has been a matter of fund-raising campaigns ("We are writing salary increases into our 1959-60 budget, even though we don't have any idea where the money is coming from," says the president of a privately supported college in the Mid-Atlantic region); of finding additional salary money in budgets that are already spread thin ("We're cutting back our library's book budget again, to gain some funds in the salary accounts"); of tuition increases ("This is about the only private enterprise in the country which gladly subsidizes its customers; maybe we're crazy"); of promoting research contracts ("We claim to be a privately supported university, but what would we do without the AEC?"); and of bargaining.

"The tendency to bargain, on the part of both the colleges and the teachers, is a deplorable development," says the dean of a university in the South. But it is a growing practice. As a result, inequities have developed: the teacher in a field in which people are in short supply or in industrial demand—or the teacher who is adept at "campus politics"—is likely to fare better than his colleagues who are less favorably situated.

"Before you check with the administration on the actual appointment of a specific individual," says a faculty man quoted in the recent and revealing book, The Academic Marketplace, "you can be honest and say to the man, 'Would you be interested in coming at this amount?' and he says, 'No, but I would be interested at this amount.' " One result of such bargaining has been that newly hired faculty members often make more money than was paid to the people they replace—a happy circumstance for the newcomers, but not likely to raise the morale of others on the faculty.

"We have been compelled to set the beginning salary of such personnel as physics professors at least $1,500 higher than salaries in such fields as history, art, physical education, and English," wrote the dean of faculty in a state college in the Rocky Mountain area, in response to a recent government questionnaire dealing with salary practices. "This began about 1954 and has worked until the present year, when the differential perhaps may be increased even more."

Bargaining is not new in Academe (Thorstein Veblen referred to it in The Higher Learning, which he wrote in 1918), but never has it been as widespread or as much a matter of desperation as today. In colleges and universities, whose members like to think of themselves as equally dedicated to all fields of human knowledge, it may prove to be a weakening factor of serious proportions.

Many colleges and universities have managed to make modest across-the-board increases, designed to restore part of the faculty's lost purchasing power. In the 1957-58 academic year, 1,197 institutions, 84.5 per cent of those answering a U.S. Office of Education survey question on the point, gave salary increases of at least 5 per cent to their faculties as a whole. More than half of them (248 public institutions and 329 privately supported institutions) said their action was due wholly or in part to the teacher shortage.

Others have found fringe benefits to be a partial answer. Providing low-cost housing is a particularly successful way of attracting and holding faculty members; and since housing is a major item in a family budget, it is as good as or better than a salary increase. Oglethorpe University in Georgia, for example, a 200-student, private, liberal arts institution, long ago built houses on campus land (in one of the most desirable residential areas on the outskirts of Atlanta), which it rents to faculty members at about one-third the area's going rate. (The cost of a three-bedroom faculty house: $50 per month.) "It's our major selling point," says Oglethorpe's president, Donald Agnew, "and we use it for all it's worth."

Dartmouth, in addition to attacking the salary problem itself, has worked out a program of fringe benefits that includes full payment of retirement premiums (16 per cent of each faculty member's annual salary), group insurance coverage, paying the tuition of faculty children at any college in the country, liberal mortgage loans, and contributing to the improvement of local schools which faculty members' children attend.

Taking care of trouble spots while attempting to whittle down the salary problem as a whole, searching for new funds while reapportioning existing ones, the colleges and universities are dealing with their salary crises as best they can, and sometimes ingeniously. But still the gap between salary increases and the rising figures on the Bureau of Labor Statistics' consumer price index persists.

HOW CAN THE GAP BE CLOSED?

First, stringent economies must be applied by educational institutions themselves. Any waste that occurs, as well as most luxuries, is probably being subsidized by low salaries. Some "waste" may be hidden in educational theories so old that they are accepted without question; if so, the theories must be re-examined and, if found invalid, replaced with new ones. The idea of the small class, for example, has long been honored by administrators and faculty members alike; there is now reason to suspect that large classes can be equally effective in many courses—a suspicion which, if found correct, should be translated into action by those institutions which are able to do so. Tuition may have to be increased—a prospect at which many public-college, as well as many private-college, educators shudder, but which appears justified and fair if the increases can be tied to a system of loans, scholarships, and tuition rebates based on a student's or his family's ability to pay.

Second, massive aid must come from the public, both in the form of taxes for increased salaries in state and municipal institutions and in the form of direct gifts to both public and private institutions. Anyone who gives money to a college or university for unrestricted use or earmarked for faculty salaries can be sure that he is making one of the best possible investments in the free world's future. If he is himself a college alumnus, he may consider it a repayment of a debt he incurred when his college or university subsidized a large part of his own education (virtually nowhere does, or did, a student's tuition cover costs). If he is a corporation executive or director, he may consider it a legitimate cost of doing business; the supply of well-educated men and women (the alternative to which is half-educated men and women) is dependent upon it. If he is a parent, he may consider it a premium on a policy to insure high-quality education for his children—quality which, without such aid, he can be certain will deteriorate.

Plain talk between educators and the public is a third necessity. The president of Barnard College, Millicent C. Mcintosh, says: "The 'plight' is not of the faculty, but of the public. The faculty will take care of themselves in the future either by leaving the teaching profession or by never entering it. Those who care for education, those who run institutions of learning, and those who have children—all these will be left holding the bag." It is hard to believe that if Americans—and particularly college alumni and alumnae—had been aware of the problem, they would have let faculty salaries fall into a sad state. Americans know the value of excellence in higher education too well to have blithely let its basic element —excellent teaching—slip into its present peril. First we must rescue it; then we must make certain that it does not fall into disrepair again.

PEOPLE IN SHORT SUPPLY:

TEACHERS IN THE MARKETPLACE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSummary of Recommendations

April 1959 -

Feature

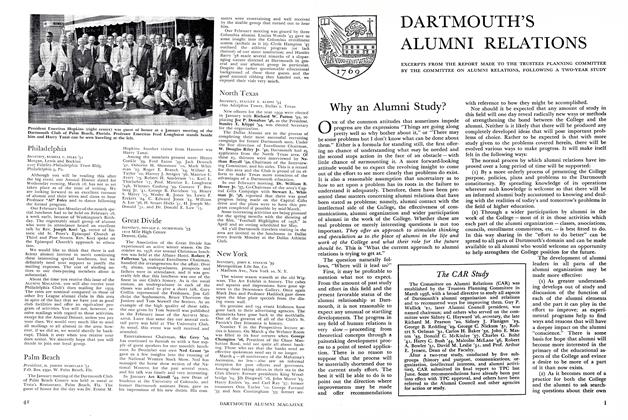

FeatureDARTMOUTH'S ALUMNI RELATIONS

April 1959 -

Feature

FeatureFuture Action and Planning

April 1959 -

Feature

FeatureTHE COLLEGE TEACHER: 1959

April 1959 -

Article

ArticleWILL WE RUN OUT OF COLLEGE TEACHERS?

April 1959 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1943

April 1959 By STANTON B. PRIDDY, LEO SILVERSTEIN JR.

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S OLDEST LIVING GRADUATE

December, 1914 -

Article

ArticleRassias in China

NOVEMBER 1992 -

Article

ArticleA Meditation on Samuel Colcord Bartlett '87

March 1931 By DR. AMBROSE W. VERNON '07h -

Article

ArticleTuck School

December 1957 By R.S. BURGER -

Article

ArticleThayer School

JANUARY 1970 By RUSS STEARNS '38 -

Article

ArticleMUSICAL CLUBS

MAY 1931 By Wilbur H. Ferry '32