We print here the remarks of Prof. F. Cudworth Flint at the memorial service for hisEnglish Department colleague, Prof. GeorgeLoring Frost '21, held in Sanborn EnglishHouse on April 1. Professor Frost died March30 at Holyoke, Mass., while returning fromNew York to Hanover for the opening of thespring term.

SUDDENLY he left us; and the shock to us was sharp and intimate. Yet better so. For we remember our friend and colleague with zest unimpaired, with wit undimmed. Who, if it lay with him to choose, would not prefer to step aside, even unobtrusively, if one could, from his daily role, instead of lingering through a dis-spiriting abatement of native vigor, until the man that was is hardly to be recollected from the man that is?

In the manner of his going, then, we, who have no gloomy views of the human spirit and of its worth, need find no cause of lamenting. Yet we may think of it as untimely. For George Frost had by no means reached the term of his service to his college and to his fellows. Indeed, it is with surprise that one remembers he was one of the senior men in his department. Coming from his native Maine to Dartmouth in the autumn of 1917 and graduating in 1921, it was but a year later that he joined the faculty of this college - first for three years as an instructor in French, and from 1925 onward in the Department of English. Had he lived only three years longer, he would have completed the fortieth year since he first instructed for his Alma Mater. Yet one cannot think of George as elderly - hardly even as middle-aged. For the alertness, the gaiety, the resourcefulness with which he encountered the experiences of each new day were those of a young man. Even during these last few years, when he was obliged in some degree to aid himself with a metal crutch in walking, he never made of this fact a symbol of limitation or defeat. He had the knack of walking with a crutch as if it were not there. And certainly, there was never any lessening of his ardor at the bridge table; only the score revealed the fact that this was a seasoned general, and not a young captain heading his first assault.

Some of us who thought we knew him well were surprised, ever and again, by some new evidence of the many-sidedness of his industry. We knew, for example, of his devotion to Chaucer - a most fitting connection, for George was a kind of person whom Chaucer would have liked. What we often overlooked was the persistence with which George unearthed and published in scholarly journals, here an identification, and there a gloss. Especially vigorous was his interest in the theater. He had a scholar's knowledge of the history of the drama; he knew also by instinct what the drama is all about. He was himself a perceptive as well as amusing mimic; and it has been one deplorable result of the cessation of Gilbert and Sullivan presentations at Dartmouth that the career of an eminently effective Pooh-Bah ceased also. But these and others of George's interests and exploits he did not advertise; he was even inclined to play them down in ordinary talk. Like a true Down-Easter, he knew a good thing when he saw it; but if the good thing concerned himself, and was his own business, he was quite content that it should be seen to be good by an audience of one, himself.

His reserve whenever speech might be thought ostentation was in George no sign of a habitual taciturnity. Especially was this true in the gatherings of his colleagues. He could be depended on for opinions sturdy in their common sense, incisive in their directness, and frequently lifted off the ground on wings of wit, in swift flight to the target of the discussion. Among his friends he was excellent as a talker and listener both. Behind his shrewd and amused glance there might sometimes lurk an unexpressed comment which, had it been expressed, might not have seemed to its recipient wholly flattering. But oftener - indeed, almost constantly - his attentiveness as well as his utterances arose from a great generosity of interest in the concerns and the affairs of others. And in their well-being, too. He liked to know because he liked to know; and he liked to know, because he wished you well.

This characteristic leads naturally on to another one, of which perhaps relatively few persons have been aware; perhaps George did not choose - again in what one thinks of as a "Down-East" fashion - to put it into words at all, even to himself. He had not only a generosity of interest in others; he had a generosity of affection for those who knew him best. But it would have embarrassed him to speak of this; he would have wished no parade of the fact. Those among you who knew him best need no assurances in this matter; and so it need be spoken of no further.

This, then, is a portrait - how clumsy and botched, you well know - of our colleague and friend, whose steps have suddenly turned aside from the daily round, to travel the path of quietness. It is altogether fitting that we meet together to celebrate the memory of George Loring Frost. But more than this, I trust, we do. By our presence here we affirm that what George essentially was and is, among and with us, is the precious key that unlocks the farthest door; it is through, as well as with, him that the meaning of life disclosed to us an unexpected and beautiful vista.

"What George essentially was" - one more attempt at this, briefly, and the last. As we pay him now our Hail and Farewell, we shall do as he would wish us to do if, so far as in us lies, we give him our "Hail" with joy, and our "Farewell" with courage.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

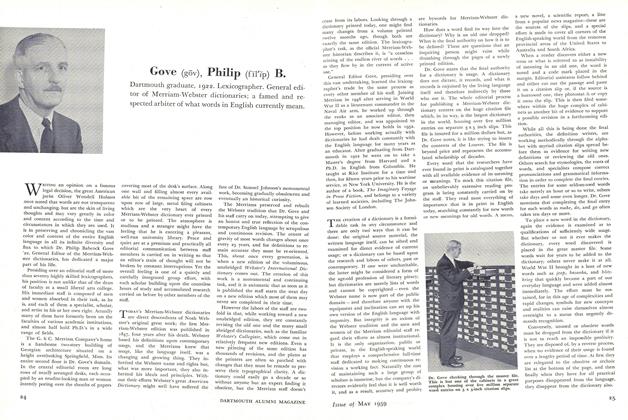

FeatureGove (gōv), Philip (fĩl'ìp) B.

May 1959 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

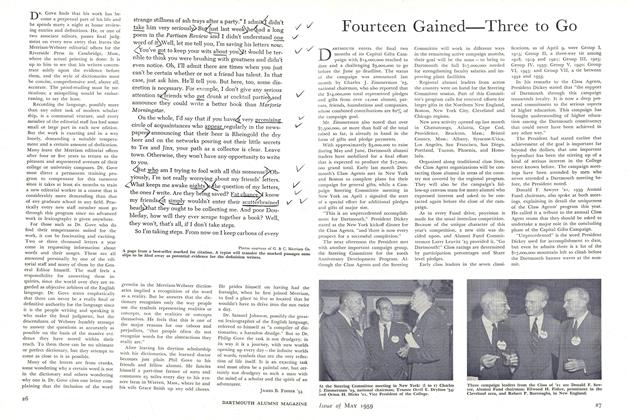

FeatureDartmouth Study Urges ROTC Program Changes to Meet Nation's Needs

May 1959 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureFourteen Gained — Three to Go

May 1959 -

Feature

FeatureWar Memorial Planned in Center

May 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

May 1959 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

May 1959 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, JAMES LeR. LAFFERTY