FACULTY advisers next fall will search their souls about what they should say to entering freshmen concerning the wisdom or unwisdom of applying for membership in one of the three ROTC units at Dartmouth. For the newcomers this is one of the most important decisions of their first year in Hanover, a decision, moreover, affecting not only their four years at college but also their choice of a career after graduation.

Most professors have too much humility to pontificate monosyllabically, "YOU DO THIS." It is not that they do not strive for omniscience. Rather, they are unwilling to indulge in what they fear may be glib advice to deadly serious eight-teen-year-old freshmen about how they should feel concerning patriotism versus self-interest, commissions versus the draft, civilian versus military careers, and liberal arts courses versus military science courses.

It is just as well. Even freshmen who are just beginning to think about ROTC can ask some devilishly searching questions.

Professor, are ROTC courses as intellectually sound and stimulating as those taught in the college curriculum?" . . "Sir, am I wise to sacrifice 20% of my time to the military when the college catalogue has a dozen or fifteen courses I am itching to take?" . . . "Professor, shall I accuse myself of being a high-class draft dodger if I sign on for ROTC in which I certainly have little interest and probably not much aptitude?... "Sir, do I really want to tie myself up for three, four, or five years after graduation? Why, I'd be 27. ... "I want to major in art or architecture and go to graduate school. Would ROTC take a dim view of that?"... "I'm sort of a lone wolf. Should I be scared of the regimentation in ROTC?" ... "Honestly, I don't know right now whether I'm coming or going."

To young freshmen, these are indeed momentous questions of a highly personal character. But to educators and military planners, there is now an even larger issue: the future of the ROTC itself. Educators decry ROTC programs because of their instability, uncertainty, and alleged interference with normal academic affairs. The military decry ROTC programs because of their failure to produce adequately the young officers needed by the services. Thus for some years the ROTC programs of all three services have been adversely criticized by both sides. If meaningful answers are to be given to the queries of freshmen each September, sooner or later solutions to these larger problems must be forthcoming.

To the resolution of basic questions about the place of ROTC in higher education, Dartmouth has recently made a significant contribution. At the suggestion of John W. Gardner, president of the Carnegie Corporation of New York and chairman of the Panel on Education of the Rockefeller Brothers Special Study Project, and with the encouragement of President John Sloan Dickey, two members of Dartmouth's Department of Government, John W. Masland and Gene M. Lyons, set out to examine the relations of higher education to the requirements of the Army, Navy, and Air Force for officer personnel. This investigation soon took them into the complex issues of national manpower requirements in science, engineering, and other professions and vocations, and into the controversial and lively debates on national educational policies. For two years they threaded their ways through the labyrinths of the Pentagon, visited academic halls and college and university administrative offices from New England to California; and they talked with responsible officers, civilian experts, and educators about the function and future of ROTC as it operates by the side of civilian curricula in some 300 American institutions of higher education.

The result of this work is a full-length book, Education and Military Leadership:A. Study of the ROTC, published last month by the Princeton University Press. President Dickey has contributed the foreword.

This volume is further evidence of the enviable reputation Dartmouth is acquiring for research and teaching in national security policies. Education and MilitaryLeadership is the second of three studies which the College has projected under grants from the Carnegie Corporation. The first, an examination of the educational preparation of professional milicluded with the publication of Soldiersand Scholars: Military Education and National Policy (Princeton University Press, 1957) by John Masland and Laurence I. Radway, also of the Department of Government. The third study, on which Mr. Masland and Mr. Lyons are currently working, is directed towards the relationship of educational experience to the preparation of civilian officials, as contrasted with professional officers, for responsibilities in the formation of national security policies.

At the same time, Mr. Radway is making an independent study of the NATO Defense College in Paris and certain civil-military issues within the NATO coalition. He recently spent several months in Europe in connection with this study. Mr. Masland also is a member of the National Security Policies Research Committee of the Social Science Research Council. This group has encouraged scholarly work through a fellowship and grants program and a number of conferences and seminars.

Dartmouth has been host to two of these affairs. Last summer, for example, ten scholars spent eight weeks in Baker Library carrying on their individual research and writing, and meeting jointly on a common investigation under the direction of Mr. Radway.

And Mr. Masland and Mr. Radway have conducted for a number of years a senior seminar at Dartmouth on the problems of national security. With Mr. Lyons they are attending still another Social Science Research Council conference at West Point in June. There, economists, historians, sociologists, and political scientists will discuss the impact upon the teachings of their disciplines by the national security requirements of the nation.

Such research and activity on a national and international level are partly responsible for the high reputation for excellent teaching the Department of Government has on the campus. Undergraduates accepted in the seminar conducted by Mr. Masland and Mr. Radway consider themselves particularly fortunate.

It may strike some observers as peculiar that three Dartmouth professors of Government, Masland, Radway, and Lyons, should become so much interested and involved in military and national security affairs. Indeed, prior to World War II, and to a certain extent even today, the study of military affairs has been looked upon with much suspicion in the academic world, although the large and popular course on the military history of the United States given by Professor Lewis D. Stilwell of Dartmouth has been a notable exception. The present group in the Department of Government is representative of a small but growing number of American scholars concerned with the overbearing influence of security requirements upon our entire national life, particularly upon the political process and the maintenance of a free society. They are convinced that an understanding of security requirements and of all their implications is necessary if our democratic way of life is to be preserved.

IT was within this broad context that Mr. Masland and Mr. Lyons looked at the ROTC. An important feature of their investigation was a two-day conference held in the pleasant surroundings of Baker Library last June. At the invitation of President Dickey, who has taken an active interest in the project since its inception, a select group of college and university presidents, high-ranking military officers, and experts in higher education, manpower utilization, and military affairs met to reexamine the ROTC programs. The participants were selected to represent different types of institutions, the three military services, and the different kinds of expert experience. Among them was David S. Smith '39, then serving as Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Manpower, Personnel, and Reserve Forces. If Dartmouth professor-authors went to Washington and many campuses for ideas, Washington and many campuses came to Dartmouth to test in strenuous sessions these ideas before they achieved some sort of stature and strode into print. Pungent and pointed though the discussions were in Baker Library's 1902 Room, violent though the disagreements, and searching though the analyses, perhaps the best talk boiled up informally in corridors and at the President's house before and after sessions, during recesses, and over luncheon and dinner tables at the Inn and Outing Club.

The conference had a double purpose: first, to give Messrs. Masland and Lyons the opportunity of testing the ideas in their projected book against the burningglass scrutiny of responsible military and educational leaders; and, second, to give these same leaders an opportunity to sit down together on neutral ground to thresh out common problems. Unfortunately in the military and educational worlds normal lines of authority provide all too few open channels of communication between the two. One of the generals, for example, declared that at the Dartmouth conference he had met for the very first time with officers of the other two services, let alone representative leaders from higher education, to discuss the operations of ROTC.

During two days of candid talk, the conference participants examined a series of issues posed by Mr. Masland and Mr. Lyons in four papers circulated in advance. At the first morning session, attention was directed to the question: How can a decentralized system of higher education based on liberal traditions best provide an adequate source of officers to meet the changing requirements of the national defense establishment? In the afternoon, the focus was upon this controversial and complicated question: What is a proper relationship between the ROTC programs and the policies of the federal government on higher education and on national manpower requirements? On the second morning, the conferees were asked: Are the objectives and methods of the ROTC courses consistent with the best ideals and purposes of American higher education? And, at the final afternoon meeting: Do present organizational arrangements ease or hinder the adjustment of the ROTC programs to changing officer requirements of the Armed Services?

Thinkers discussing such broad issues cannot help coming around to problems dimly envisaged by harassed freshmen boring in on professors conscious of their lack of military crystal balls. Advisers no less than freshmen have been conscious if inarticulate about the dichotomy involved in having ROTC units in liberal arts colleges. In times past, the military have viewed ROTC only in military terms: endurance, austerity, discipline, responsibility, deferential manners, neatness of dress, recognition of authority, and instantaneous obedience. In times past, the faculty, committed to their ideals about the perpetual search for values, incessant study, letting the books lead whither they will, and education as intellectual adventure, are likely to condemn ROTC, which, they assert, kills initiative, deadens interest, thwarts creative reasoning, and withers imaginative aspiration.

Officers in uniform point out, however, that if the services cannot rely on institutions of higher learning to give them the raw material for leaders, the values of the liberal arts may be cancelled out by Hbombs. Before World War II, these officers keep insisting, it was admirable and exciting to look on education as simply intellectual adventure, but in 1959 we live in a world dominated by an increasing reliance on scientific skills and military power.

Thus, though in different ways and with different emphases, both military and liberal arts educators are concerned with the dimming of the lights of intellectual freedom all over the world. The adjustments to be worked out between these two positions are at the basis of the Masland-Lyons research and book.

In the foreword to Education and Military Leadership, President Dickey has pointed to the nature and urgency of the problem: "The central issue of the whole business seems ... to focus squarely on whether the traditional concept of the ROTC is adequate to the national security requirements of this nation in the foreseeable future. If there is real doubt about this, then, I think, there can be little doubt about the need for some very fundamental changes in the entire setup with a strong educationally oriented lead being given from above and outside, and the sooner the better.'

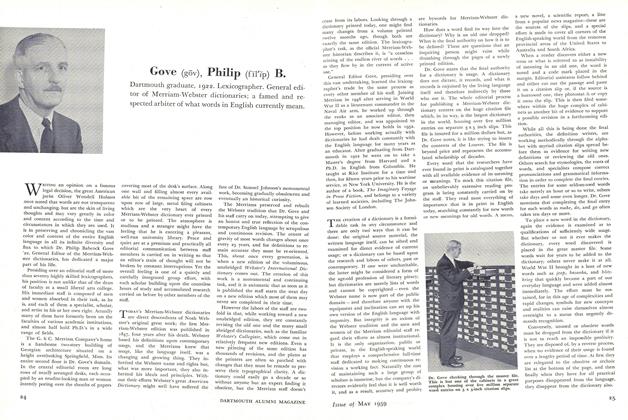

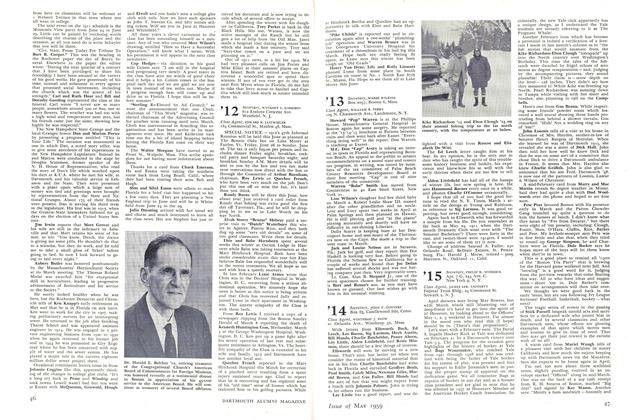

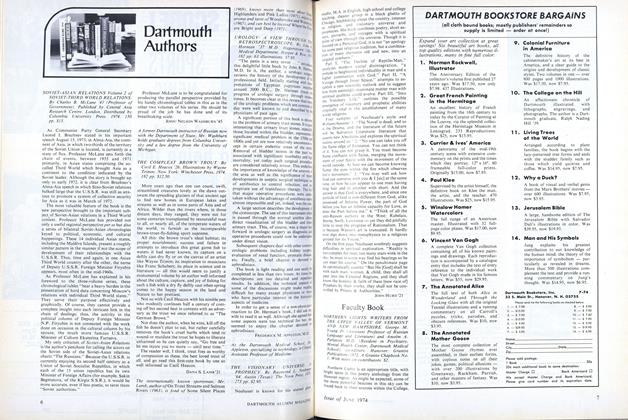

Other conference participants were (l to r) Walter Millis author and representative of The Fund for the Republic; President J. L. Morrill of the University of Minnesota, Dr. Earll J. McGrath executive officer of the Institute of Higher Education, Teachers College, Columbia University; James A. Perkins, vice president of the, Carnegie Corporation of New Youk; and Major General Turner C. Rogers, commandant of the Air Force ROTC, Air University.

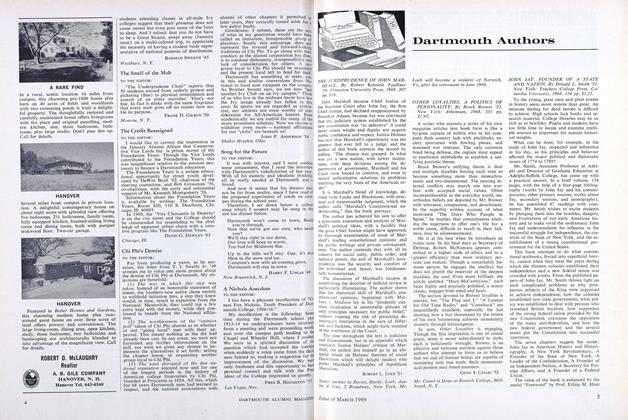

Professor Masland speaking at the Dartmouth conference last June. At the table, clockwise, are Major General John W. Bowen, assistant chief of staff for reserve components, department of the Army; Col. Joseph Chabot, director of the reserve affairs policy office, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense; Brig. General T. J. Conway, director of research Office of the Chief of Research and Development, Department of the Army; Rev. Dr. Thomas C. Donohue, academic vice president of St. Louis University; Gene M. Lyons of Dartmouth, President Dickey; Professor Masland; Rear Admiral John T. Hayward, assist:ant chief of Naval operations for research and development, Department of the Navy; and (partly shown) L. Eugene Hedberg, staff director, Reserve Forces Policy Board, the Secretary of Defense.

June conference participants, shown in the 1902 Room of Baker Library, are (l to r) President Frederick L. Hovde of Purdue University; Raymond F. Howes of the American Council on Education; President Barnaby Keeney of Brown University; Col. George A. Lincoln of the Department of Social Sciences, U.S. Military Academy; William W. Marvel, of the Carnegie Corporation of New York; and Walter Millis, authour.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGove (gōv), Philip (fĩl'ìp) B.

May 1959 By JAMES B. FISHER '54 -

Feature

FeatureFourteen Gained — Three to Go

May 1959 -

Feature

FeatureWar Memorial Planned in Center

May 1959 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

May 1959 By HAROLD L. BOND '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915

May 1959 By PHILIP K. MURDOCK, JAMES LeR. LAFFERTY -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

May 1959 By HOWELL D. CHICKERING '59

JOHN HURD '21

-

Article

ArticleThis Mother of Seven Dartmouth Sons Read Every Book in the College Library

DECEMBER 1965 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksNINETEEN DARTMOUTH POEMS.

MAY 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksENGINEERING: ITS ROLE AND FUNCTION IN HUMAN SOCIETY.

JUNE 1968 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksJOHN JAY, FOUNDER OF A STATE AND NATION.

MARCH 1969 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksTHE VISIONARY UNIVERSE PROPHECY.

June 1974 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksVice in Its Gayest Colors

June 1975 By JOHN HURD '21

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe First Year

September 1993 -

Cover Story

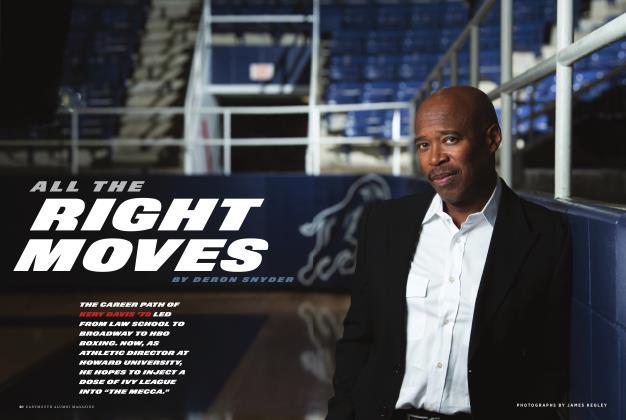

Cover StoryAll the Right Moves

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By DERON SNYDER -

Feature

FeaturePacifism and Other Issues: A Survey of 1960 Attitudes

June 1961 By E. PETER STARZYK '60 -

Feature

FeatureRev. Frisbie's Wonderful Discovery

MAY 1978 By James L. Farley -

Feature

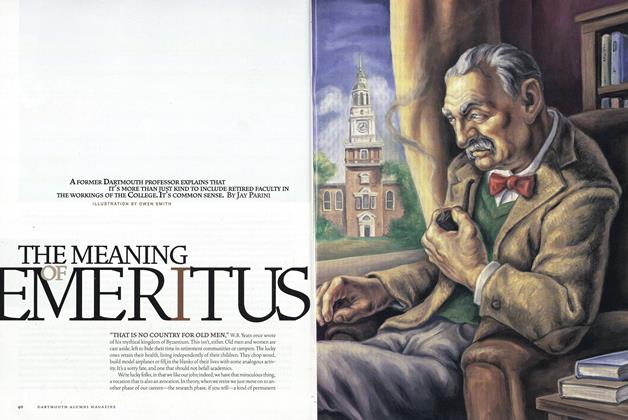

FeatureThe Meaning of Emeritus

July/August 2001 By Jay Parini -

Feature

FeatureThe Human Revolution and World Peace

May 1961 By RICHARD W. STERLING