TECHNICALLY, a valedictory address is an oration of farewell and leave-taking. Traditionally, it has been a vehicle for commentary on the benefits experienced by the graduating class during their years at college, or for prophetic utterance regarding their future in the larger world.

This morning I will not attempt to make an explicate, sufficient, and suitably decorated statement of farewell; nor will I attempt a thorough review of our college years, or a detailed prediction about our future lives. It seems more appropriate to concentrate on the present moment and the commencement act itself.

To compromise the extremes of formal definition and no definition, three characteristics of commencement that seem evident and important will be mentioned.

In a functional sense, commencement is the termination of a four-year stretch at college. Formal ties are broken, certain opportunities vanish, and some pursuits permanently halt with this significant ending occasion. In a linguistic sense, commencement is an auspicious beginning event. Many an address has treated this aspect of commencement, and little need be said. In an emotional sense, commencement is an occasion for great joy and celebration. Those involved in a commencement ceremony experience feelings of inner warmth and happiness.

All three of these aspects must be recognized and included in a satisfactory search toward the meaning of commencement. All three are fundamental to the basic problem. "How does the act of commencement, as an ending and as a beginning, join past and future in a manner that provides an adequate basis for a joy-ful response? What is the character of the commencement act itself?"

The content of our college years is the raw material for understanding the approaching commencement in its ending sense. The diverse situations and adventures i ncluded in the college experience cannot be directly tapped for an estimate of value; they are too heterogeneous. But the content of experience is both objective and personal. When personal response to these non-uniform stimuli is considered, an estimation of the whole can be made. Individual response digests objective experience, and, in the present case, the final appraisal is positive. Most of us feel and claim they have profited from the diverse, uneven, and occasionally contradictory events of college.

We are going from college into life in a larger world through the commencement act, with a positive synthesis of our college experience. What can be said about this larger world?

Man's life responsibilities are shaped by his presence in history; life responsibilities depend on a time and place basis.

The primary outlines of the time and place situation given to us are plain. Our recent past gives us every reason to expect continuing, accelerating change in technology, political attitudes, and life patterns; our time will be a time of change. Our place situation is not so evident, yet differences in responsibility, caused by differences in locational factors, are being overshadowed by responsibilities common to all men living on the same shrinking globe.

Life provides every man and generation with a time and place situation containing difficult challenges and duties. Other men in history have faced up to life-given trials with both success and failure; we

can temper our response to life in a time of great change, and on a small globe, in this perspective. The present situation may be unique in content, but not in kind.

This is true, neglecting one fact. Other generations have been aware of the ugliness of irrational nationalism, but ours is the first to see this demonic force magnified grotesquely by the existence of nuclear weapons; ours is the first to live in the presence of a destructive capacity able to terminate history. The given situation will make infinite demands upon our talents and courage, and it makes our failures to meet certain responsibilities unforgivable.

We are going from college into life in this larger world through the commencement act. The logical and important question is: "Are we ready for what lies ahead? Did the college experience we are now ending prepare us adequately for the life experience we are now beginning?"

As mentioned above, most students have a positive estimation of their college experience. But, in view of what lies beyond commencement, that positive estimation must be realistic.

Let us pause a moment.

A physicist is faced with an educational dilemma. He must strive to achieve new knowledge and experience in physics; he must also develop within himself the analytic skills of abstract mathematics. Either one of these educational goals demands his full time and effort; how can he achieve both?

A month ago I heard a student make the following comment after Paul Tillich's lecture on ethical norms: "... if I trust my own insight in applying his principles of justice, love, and wisdom as to what is a moral action in a given situation, I might do a very immoral act. My honest personal decision might well be wrong from an absolute point of view. How can a person live morally without the necessary insight and perceptive ability?"

In both of these instances, one is unable to act because of inadequate knowledge, yet has to act. The physicist cannot delay his basic research efforts until he has mastered all of mathematics. A man cannot delay his actions until he has acquired perfect insight and wisdom. Both are faced with the necessity of going ahead, to work and live, knowing that they possess only fragments of the essential prerequisites for their tasks.

This necessity is presented in countless life situations, and in commencement in particular. Today we are leaving the College, having assimilated four years of its care and effort on our 'behalf; we recognize our stay at Dartmouth to be a precious advantage, but in our honest moments we also recognize it to be an inadequate preparation for what lies ahead. Today, although we are unready, we move ahead to responsible thought and action in the larger world.

It should be noted that the fundamental situation, in which one must make a positive decision to move forward in spite of great risk, is influenced by institutional factors. The institutional structures associated with this commencement, with marriage, with Communion in the Christian Church, or with countless less important forms, affect the individual and his personal, lonely decision. They frame his choices and assist him in seeing them through once they are made.

We have identified the essential process of the commencement act, and now must look for the basis it provides for a joyful response. How can our conclusion, that commencement implies stepping forward to life demands in spite of being inade-quately prepared, support the joy we all feel this morning?

The answer is simple, and perhaps obvious. As man acts in faith, he overcomes the discontinuity splitting ability and task, past and future. As man responds courageously to his human, time-bound condition, he causes a rare sense of joy within himself and for others. His faith and courage extend the dimensions of his own life, and make membership in humanity more wonderful for all. Commencement provides a broad basis for such joy, through the larger number of people whose personal joyful responses are focused in one public occasion. At commencement we joyfully celebrate not just past achievements, or future promise, but the heroic action of going on, in spite of being only partially competent. We celebrate the present moment and its act.

John E. Baldwin '59

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

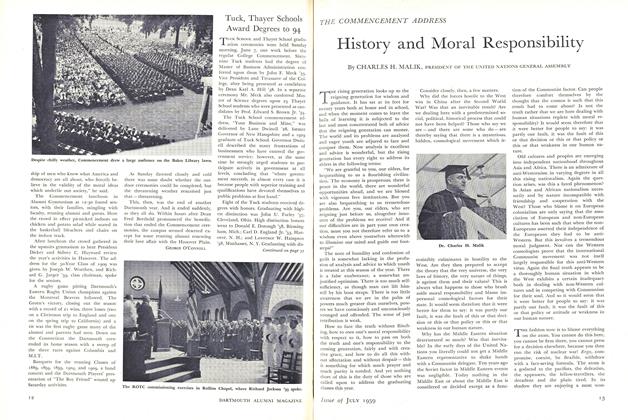

FeatureHistory and Moral Responsibility

July 1959 By CHARLES H. MALIK -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1959 By JOSEPH W. WORTHEN '09 -

Feature

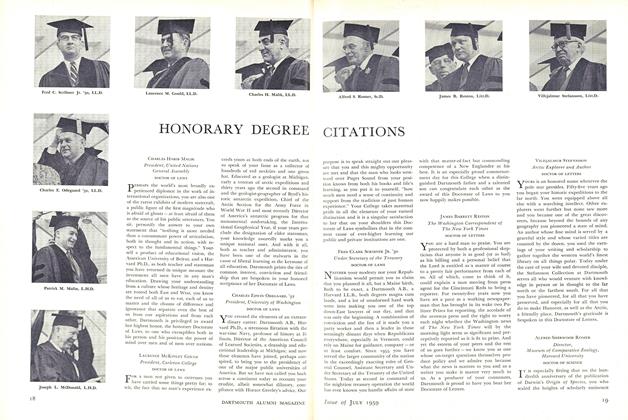

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1959 -

Feature

FeatureFor Distinguished Service . . .

July 1959 -

Feature

FeatureThe 190th Commencement

July 1959 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1959

Features

-

Feature

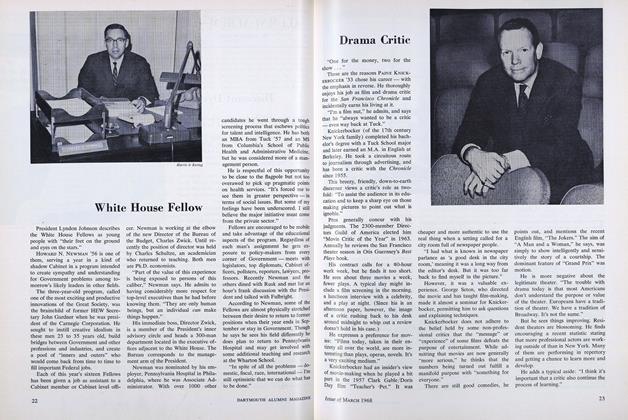

FeatureDrama Critic

MARCH 1968 -

Feature

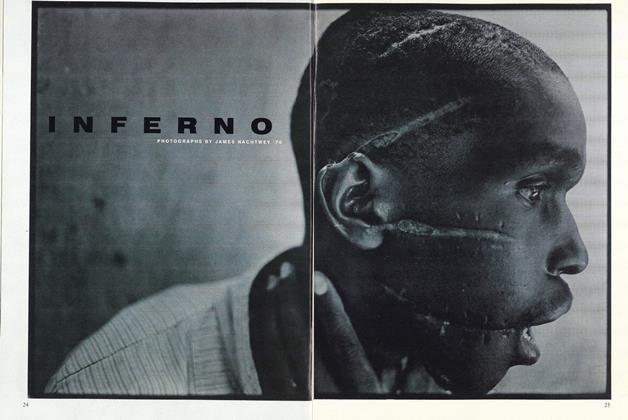

FeatureInferno

JUNE 2000 -

Feature

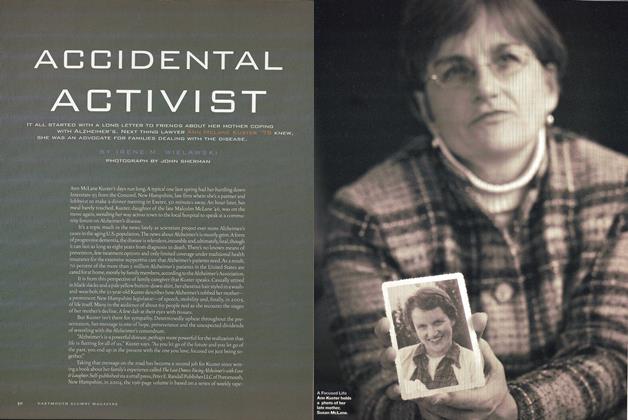

FeatureAccidental Activist

May/June 2008 By Irene M. Wielawski -

Feature

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

Nov/Dec 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

Feature

FeatureWhere Are the Silver Cornets? or Twenty Versts to Nizhni Novgorod

By KENNETH ALLAN ROBINSON -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Section 504

DECEMBER • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77