IN each successive annual period of commencement, such as this, it has been customary, as you know, to invite some sort of statement from one of those who, like us of 1909, think of our own real class commencement not as a day or a week, but as four years of rich and varied life together on this campus, half a century ago. And at this time it might well be of interest to follow the example of some of my predecessors and try to summarize in briefest outline just what, for us, the period of life which then commenced has proved to be. Meanwhile the achievements of many of my classmates have been indeed impressive; yet I am sure that all of us are in accord on this, that whatever may be the objects of our attention or concern elsewhere, at this long-awaited reunion neither our activities nor their results are paramount nor even consciously present, at all, in our minds. So during the next few minutes I hope to lift the shades of reticence high enough to let you look quickly in and see what it is, here and today, that takes their place.

First, I think you will find memory - memory which fills us not with sadness but with gratitude. Those whom you see here present as our reuning class are but a meager fraction of those whom we see here ourselves. Especially here in Hanover we seem to see men always moving through our memories - some sharply here, a group more vaguely there, with cithers still beyond — just as we used to watch the shadowy figures moving silently across the campus on early autumn mornings long ago, when the river mist had billowed up and shrouded it and them and all our little world in quietness and peace.

We see and hear Ralph Lauris Theller, perhaps the most gifted and eloquent speaker of our generation in this or any other New England college, who was taken from us at the close of the very first decade after graduation, forty years ago. We see Frederick Aloysius Carroll and Philip Minot Chase - both original, talented, successful, lovable. Any one of these, had he but lived, would to your very great advantage be speaking in my place today. But may I hasten to add that they and others so lived themselves into the lives of us, their friends, that in a very real sense they also are speaking to you today. Clearly too we see scores of others, very close to us, whom most of you cannot perceive. So as we return at the close of fifty years to Hanover and Dartmouth, the campus which we see and think about is not alone the living, bustling college center of today, nor yet the more imposing, doubtless even better campus of tomorrow. It is as well that misty campus of our memory, with all those fine, beloved boys upon and round about it, who are - for us - forever young.

While still referring to memory, may I hark back to nearer seventy than fifty years ago, and briefly recall, as one of the so-called "Faculty Kids" of the eighteen-nineties, a few random glimpses of the Hanover of that day. Then on two sides of the campus stood colonial or other early dwellings, facing what was then the only Dartmouth athletic field, where full-back Charlie Proctor proved to be - but would never admit it himself - the finest punter in the college; and where student participation in varsity baseball was wont to take the form, along about the seventh inning, of crowding the first and third baselines to rattle the pitcher and razz the catcher from Amherst or Williams or Brown.

Shortly before, the campus had been encircled by a fence, for vaulting which a young and vigorous member of the faculty had been called on the carpet by the Victorian President Smith and sternly told: "Tutor Worthen, it will be more consistent with the dignity of the college faculty, of which you are now a member, if hereafter you will use the campus gates." So far as I can discover, that episode had two sequels: Tutor Worthen then proceeded to work off some of his surplus energy by teaching all freshman gymnastics for the next twenty years, without compensation; and, in the also unpaid job of Superintendent of Buildings, in addition to his teaching of mathematics, helped bring about the removal of that campus fence - all but a few lengths reserved in perpetuity as an honorable and exclusive place of deposit of certain members of the senior class.

Necessarily in those days, far more than now, the village and the college community together were self-sufficient. Visitors of wide renown were relatively rare, yet there were other visitors of even keener interest to some of us. Once or twice each year, down from the then distant and mysterious world referred to as the "north country" came gangs of husky, rough and ready rivermen, shouting and singing in vivid, racy language of their own, shunting with their cant hooks the drives of logs downstream.

Stranger still were the several hundred Sicilian laborers with pick and shovel, brought in, one summer, to construct the present reservoir - to build its dam and dig and fill the ditches down to this village. First on their arrival they burrowed into the steep, short hillsides of the so-called Vale of Tempe, making their little caves and lean-to's in which to live, traces of which can still be seen a scant half mile from here. Fascinated were the youngsters who watched them around their evening campfires, listening to their songs and incessant chattering which none of us could understand. All summer long they dug in dirt and sun, with not a drop of water near except to drink. Children's sensations are vivid; and after some 65 years I can still remember as if it all were yesterday the impressions made by those swarthy, tireless little men on eyes and ears and nose.

From the dwelling house where I was born - later enlarged and converted into the Crosby House - every morning at 6:50 on the dot, winter or summer, snow or rain or shine, we could see Johnny McCarthy, the town barber, walking up across the campus, carrying the little black satchel containing his equipment with which to give President Tucker his morning shave. Not only in great matters was Dr. Tucker in a class by himself. And it was the privilege and fortune of the boys of Hanover to know, and know well, not only the Tuckers but the McCarthys; to admire character and also to love characters; to have among our neighbors a whole group of "Mr. Chips" before that name was ever written, and to learn gratitude for all those kindly and devoted men and women, of town and gown alike, whose presence blessed this village, and made its life simple and clean and altogether happy.

All this, I fear, is a departure from my role as a member of my class into that of one born in Hanover 71 years ago. But in a perhaps too bold attempt to describe something of what lies in the mind of a graduate of fifty years, it is one aspect of the memory which, if you should care to glance today through my own mental window, you would first discover.

What you would find next, I think, in the minds of all of us oldsters, is fellow-ship, based on affection which somehow in a class like ours seems to grow ever stronger and more concentrated as the living ones of those for whom it is felt grow fewer. In the earlier years of graduate life, while families are being established and professional or business and public responsibilities are also steadily growing, it is far too easy to permit a sag in college interest. But then, sooner or later, for most of us there comes a time when the hill winds bearing thoughts of Hanover seem to freshen, and we become aware - perhaps more deeply than ever before - of the strength and the warmth and richness of the early friendships forged around this campus, In work and sport and laughter and song, and in common devotion to this college, when all the world was young.

As you well know, we Yankees do not carry our hearts on our sleeves, and do not care to speak too much about such matters. But a notable exception, at least on occasions such as this, was Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes of the Harvard Class o£ 1829, who was frequently - and very understandably - asked by his classmates to write simple verses for their reunions. So with reference to this quality of fellow-ship it seems appropriate - in this month of what would have been his 130th reunion - to quote briefly from them:

Come, dear old comrade, you and I Will steal an hour from days gone by, The shining days when life was new, And all was bright with morning dew, The lusty days of long ago When you were Bill and I was Joe.

You've won the great world's envied prize, And grand you look in people's eyes, with HON. and LL.D. in big brave letters, fair to see, Your fist, old fellow! off they go! How are you Bill? How are you, Joe?

The chaffing young folks stare and say "See those old duffers, bent and gray,- They talk like fellows in their teens! Mad, poor old boys! That's what it means," And shake their heads, they little know The throbbing hearts of Bill and Joe!

Ah, pensive scholar, what is tame? A fitful tongue of leaping flame; A giddy whirlwind's fickle gust, That lifts a pinch of mortal dust; A few swift years, and who can show Which dust was Bill and which was Joe?

No matter; while our home is here No sounding name is half so dear; When fades at length our lingering day, Who cares what pompous tombstones say? Read on the hearts that love us still, "Hie jacet Joe; hie jacet Bill."

And now as you take a last glimpse through that mental window of any member of my class, you will also find confidence, sustained and strengthened by memory and fellowship, and accompanied perhaps by a gradual change in our sense of relative values, with a determination

to put them to an ever more vigorous application while we may. In the meaning of the words which Cicero in his Dialogues a scribed to Marcus Cato the Elder just under twenty-one centuries ago: "Can there be anything more absurd than to seek more journey money, the less there remains of the journey?" Yet we can remember with a new understanding and appreciation the letter from Benjamin Franklin to his old friend Dr. Bond:

"Being arrived at seventy, and considering that by travelling further in the same road I should probably be led to the grave, I stopped short, turned about and walked back again; which having done these four years, you may now call me sixty-six."

Indeed it was in that spirit, some three months ago, that my attention was arrested by one of the most conspicuous headlines ever seen in one of our most conservative newspapers, which fairly shouted all across the top of its front page; "Radar Bounces off Venus!" After marveling at the magnitude of that scientific achievement, I re-read the headline; and it then occurred to me that even at our age, fifty years out of college, some of us might be perfectly willing, once in a great while, in the interests of science, to offer our services as spacemen.

But the confidence which I want especially to emphasize is something else again. It is a confidence not only in ourselves but in this College - in its enduring vitality, in its vision, and most of all in its service and achievement in striving so effectively to change successive generations of fine young lads into educated and dedicated men; and also, in so doing, and as a sort of priceless bonus, giving to every one of them, for life, a focal point for loyalty.

What that focal point for loyalty must be, need not be told to any Dartmouth man. Yet surely it is fitting that we hear it once again in the words of William Jewett Tucker, spoken at our own commencement in his last address as President of the College:

"When our hearts turn hitherward, we must not be afraid of sentiment. Let the Mother of us all know, by visible and enduring signs, that you love her. Let her never be ashamed, in any respect, for herself, not simply for her sons, as she stands with the years falling upon her in the midst of the older and the younger colleges of the land. Better yet, see to it that her strength is as the strength of the hills which guard her, and her beauty like their beauty - simple, true, sufficient."

And now, in finally lowering that curtain, may I close by saying simply this: that until it comes time for us of 1909 to join the other members of our class on that misty campus of memory, to which so many of our best have gone too soon, we shall continue in that loyalty; and shall continue also to believe, thankfully and confidently, just as they themselves believed, with the great Irish playwright:

"Life is no brief candle for me. Rather it is a sort of splendid torch which I have got hold of for a moment; and I shall make it burn as brightly as possible before handing it on to future generations."

Joseph W. Worthen '09

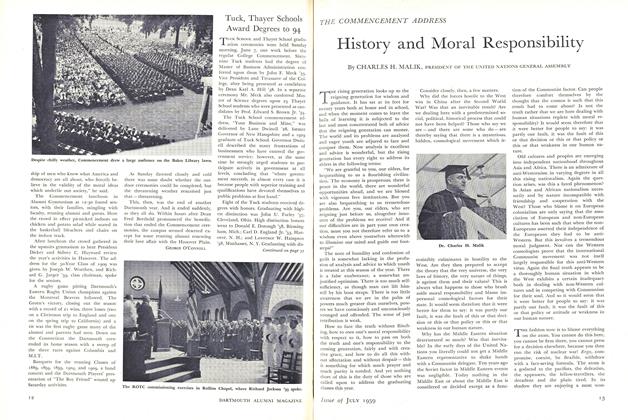

The Dartmouth Glee Club performing on the stage of the Radio City Music Hall, New York City, where it is the hit of "Bonanza," the stage show saluting the admission of Alaska into the Union. The show opened June 18, in conjunction with the movie, "The Nun's Story," and will continue as long as that movie runs, up to a maximum of eight weeks (to August 12). The Dartmouth men's performance drew praise from all sides and led to an offer to them to perform in the next stage show too, but the College calendar won't permit that, even if the singers could keep up the strenuous schedule of four shows a day, seven days a week.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHistory and Moral Responsibility

July 1959 By CHARLES H. MALIK -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1959 -

Feature

FeatureFor Distinguished Service . . .

July 1959 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1959 By JOHN E. BALDWIN '59 -

Feature

FeatureThe 190th Commencement

July 1959 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureThe Reunion Week

July 1959

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1969

JULY 1969 -

Feature

FeatureThe Speech

SEPTEMBER 1987 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFashion Corner: Two Outing Club Looks

NOVEMBER 1989 -

Feature

FeatureOPTIONS & ALTERNATIVES

March 1976 By D.N. -

Feature

FeatureWearers of the Green

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Jim Kenyon -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Study Urges ROTC Program Changes to Meet Nation's Needs

MAY 1959 By JOHN HURD '21