A TRI-MONTHLY SUPPLEMENT TO THE DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE CONTINUING THE EDUCATIONAL RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN FACULTY AND ALUMNI OF THE COLLEGE

PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT

GOVERNMENTAL regulation of the radio and television industry is burdened with conflict and controversy. Broadcasters are often split into opposing camps which make contradictory demands upon the Federal Communications Commission. Critics, pressure groups and Congressmen often wage holy wars against both the industry and the Commission.

The job of regulation is therefore a very difficult one, as will be demonstrated by a number of problems with which the FCC is now struggling.

Frequencies for TV

The broadcasters depend upon governmental regulation for the very existence of their businesses. Vital to them is the allocation of frequencies upon which they can beam their programs to the public. It is logical, therefore, that in this field of regulation there is no voice in the industry demanding old-fashioned rugged individualism. This does not mean, however, that all broadcasters agree on what the FCC should do. To the contrary, what some want, others often oppose. This conflict is due to the fact that specific regulations affect individual broadcasters differently; what is beneficial to one may be injurious to another.

Television's need for a home in the spectrum is presenting the FCC with one of its most difficult problems. When the Commission, toward the end of the last war, undertook the task of making an allocation it unfortunately found that there were many other services - for example, FM, Navy, Army, Maritime Commission, FBI, and other policing agencies - demanding channels in the same part of the spectrum. It was apparent, therefore, that enough room could not be found in the very high frequencies (VHF) to permit the growth of the new industry to its maximum potential. In fact, channels 2-13 are all that the FCC has been able to save for TV, and everybody has agreed that this is not enough. The lowest estimates urge at least 25 channels.

When the allocation was made, therefore, the Commission urged the industry to work on the opening of the ultra high frequencies (UHF) above 480 megacycles for future use. By the time the engineers got around to doing this, however, it was too late. The VHF had become entrenched with the public; there were many VHF stations on the air, and the number of VHF sets in the homes of the country could already be counted in the millions. Moreover, the propagandation characteristics of the UHF proved to be poor in mountainous terrain. Hence, few newcomers have applied for stations on these frequencies, and many of those who did subsequently gave up the ghost when they lost money and their future prospects continued to be dim. Manufacturers therefore have continued to produce VHF sets in numbers and UHF sets in driblets.

Many solutions have been considered. In the first place, room for more telecasters on the existing VHF channels could be found by reducing the power of stations and the geographical separations between them, or by requiring them to use directional antennas. But, the VHF stations have uncompromisingly fought against such regulations. They don't want their service areas and audiences, and hence their profits, reduced. In waging their war, they have charged that the adoption of the proposed restrictions would be tantamount to forcing stations into the spectrum "with a shoe horn." Secondly, more frequencies for TV could be found in the VHF if governmental agencies, and particularly the armed forces, would give up some of the ones they have preempted. In support of this proposal, broadcasters have charged that the Office of Civilian and Defense Mobilization has been guilty of "grabbing" more frequencies than it needs; the unused ones are "put on ice." One trade periodical has called the government an "ether road hog." But, despite these attacks and demands, the OCDM has been refusing to surrender any frequencies on the ground that they are "necessary for national defense."

At the present time, this latter solution is receiving much attention, and an attempt is being made to get some frequencies from the OCDM either by negotiation or by the enactment of compulsory legislation. The conflict, however, is keen. The FCC wants to foster freedom of enterprise for more newcomers to the television business and to give the public a greater choice among stations and programs. On the other hand, military needs for space in the spectrum are increasing because of the recent developments in electronics. A solution will not be easy.

Censorship

In the field of programming, as contrasted with frequency allocation, the industry's cry is for self-regulation and against governmental regulation. In support of their demands, the broadcasters are relying upon Constitutional and statutory prohibitions against censorship and against interference with freedom of speech. The specific issue is whether the FCC is denied authority to consider programs in granting, renewing, and terminating station licenses.

Ever since the beginning of broadcasting, there has been a running controversy over the interpretation of censorship; the debate has raged in Congressional committees, in argument before the Commission, and in cases in the courts. According to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, censorship must be defined as previous restraint in a narrow, technical and formal legal sense. That is, if the FCC were to require programs to be submitted to it for its inspection and approval as conditions precedent to the right to broadcast such programs, that would be censorship. On the other hand, if the Commission should take a license away from a station on the grounds that the programs it had been broadcasting in the past were in violation of the station's duty to serve the public interest, that would not be censorship. In other words, the regulation of programs is not per se censorship.

On the issue of freedom of speech, these decisions of the Court of Appeals deny the protection of that right to programming practices which do violence to the public interest. Therefore, if the Commission's decisions in its license cases are in the public interest, freedom is not being abridged.

These cases also use strong and positive language in sustaining FCC authority. For example, in one case the Judges declared that "the Commission is necessarily called upon to consider the character and quality of the service to be rendered." In another case, the Court said that the Commission has a "duty in considering the application for renewal to take notice of appellant's conduct in his previous use of the permit." (Italics mine.)

Finally, it must be emphasized that the United States Supreme Court has never overruled these precedents. In fact, it was given a number of opportunities to do so when losing parties tried to appeal, but it refused to take the opportunities by denying the petitions for certiorari. Moreover, although this top Court of the land has spoken in broad terms of freedom of speech in cases involving the other media, these statements must be relegated to the status of obiter dicta. The conclusion is unavoidable; the lack of adjudication in the Supreme Court means - and it must mean - that the rulings of the Court of Appeals remain the final authoritative statement of the law. That is the American system of jurisprudence.

Despite this judicial record, the controversy continues. For example, a number of attorneys have recently filed briefs with the Commission challenging its authority. Commissioner T. A. M. Craven has insisted that program regulation is censorship and Chairman John C. Doerfer told a Congressional investigating committee that the statutory prohibition against censorship prevented the FCC from taking action in the quiz fix scandal.

Whatever the right or the wrong, the mere existence of this controversy has raised an inhibiting doubt. When this restraint meets the strong pressure which is currently demanding program regulation, the Commission is indeed placed in an uncomfortable position.

The Death Sentence

FCC termination of a station's license is known in the industry as the "death sentence." The penalty is very severe; by its decision, the Commission can destroy a going business concern worth millions of dollars. The only check is a judicial one. The condemned can appeal to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia which can save him, but only on the grounds that the FCC has exceeded its statutory authority, has not given a hearing or has given an unfair hearing, or does not have evidence to support its decision.

Due to the extreme nature of the procedure, the Commissioners have always been reluctant to invoke it. In fact, they have never been disposed to run after the broadcasters with an axe. Executions have therefore been rare, and the FCC has often chosen reform in preference to punishment. Hence, where a broadcaster has been giving a meritorious service to the public, the FCC has traditionally preferred to give him an opportunity to cure his occasional lapses instead of dragging him to the block and thereby becoming guilty itself of injuring the public interest.

The severity of the penalty has also led to a search for procedures short of the death sentence. Many years ago, the FCC began to send to the stations those complaints it receives against their programming practices, to ask for explanations, to issue warnings and statements of program standards which it judges to be essential to service in the public interest, and to put licenses on temporary renewals pending reform. These procedures are coercive because the threat of the death sentence remains dangling in the background; stations cannot afford to be defiant or unresponsive because they might be putting their very existence at stake. Hence, these informal procedures have been dubbed in the industry as "regulation by the raised eyebrow."

Congressional committees have often considered still other procedures; among them have been fines, cease-and-desist orders, and short-term suspensions of licenses. All have met objections from the industry. Among the reasons given have been that they would reduce audiences and revenues; these results would make the stations less able to provide public service programs and therefore would decrease their capacity to serve the public interest. Inasmuch as the expansion of this service is the raison d'etre of regulation, these procedures would frustrate the very purpose for which they would be invoked. Behind this objection, however, is the opposition of the industry to any FCC regulation of their programs. The broadcasters do not want to admit any such authority, and the enactment of new procedures in a statute would be tantamount to an express grant of power to regulate. Also, the industry knows that if some less drastic procedures were to be legislated, and the inhibition which arises out of the severity of the death sentence thereby removed, they would get regulated more often than they have been in the past.

Despite the obstacle of the death sentence, the pressure for regulation has recently been mounting. In the past year there has been a growing volume of protest against alleged program offenses, which has now reached the proportions of a roar. The criticism charges excessive advertising, too many spot announcements during station breaks, deception and bad taste in plugs for patent medicines and cosmetics, and neglect of cultural programs. The current quiz fix and payola scandals have been the latest additions to this list of complaints. In December, the FCC heard testimony from a spate of witnesses demanding that strong, and sometimes extreme, measures be taken against the broadcasting industry. Among the complainants are pressure groups, clergymen, educators, authors, newspapers and magazines. Even some advertisers, some advertising agencies, and some of broadcasting's leading executives and personalities have been saying publicly that the industry has failed to maintain adequate standards. Finally, some rebellious stations have been adding to this pressure for regulation by their offensive practices. They have been defiant of the FCC and of their own codes; known as "bad actors" to their brethren in the industry, they could not do more than they have done to bring on governmental regulation of themselves, even if they were to try deliberately to accomplish this result.

The cloud on the horizon is bigger than a man's hand. As a result, governmental regulation can be expected to become more severe in the near future. Already, the performance of the industry is under investigation by the FCC and Congress. The Department of Justice has rendered an opinion sustaining FCC authority to regulate and criticizing it for a lack of vigorous and aggressive enforcement. The Federal Trade Commission is expanding its examination of broadcast advertising. New regulatory legislation is beginning to appear in Congressional committees.

But, such turbulence is not new in the life of the FCC. It had some rough years in the 1930s and the 1940s when it was also pressured into increasing its regulatory activities. Moreover, if this past experience is any guide, the current flurry will pass and the Commission will once again find itself in a relatively quiet period - until a new storm of criticism and pressure repeats the cycle.

Double Jeopardy

As if the foregoing problems were not enough, conflicts over the regulation of competitive practices have made the Commission's job still more difficult.

In the first place, the Federal Communications Act permits the termination of the license of a broadcaster who is guilty of violating the antitrust laws. The industry has often protested that this provision creates a double jeopardy; under the antitrust statutes, they can be criminally prosecuted in the courts, sued for triple damages, and ordered to change their practices - and then, subsequently, their businesses can be destroyed by the FCC. On top of double jeopardy, the broadcasters have argued that they are subjected to unfair and discriminatory treatment because other business men may be taken to court under the first procedures but are not sentenced to death.

The Commission has been sympathetic to these complaints. As a result, it has refrained from invoking the death sentence in antitrust cases. In two recent illustrations, licenses were lost - but this was done in the United States District Courts when defendants entered into consent decrees to sell their stations which were involved in antitrust litigation. A second difficulty has arisen out of the disagreements which have appeared between the FCC and the Department of Justice. There are two recent illustrations in point.

When NBC and Westinghouse Broadcasting Company exchanged their Cleveland and Philadelphia stations, the FCC approved the transfer of the licenses despite allegations that NBC had used economic coercion to force WBC to agree to the deal. The Department of Justice, however, brought a case in the courts on charges of a violation of the antitrust laws. After extended litigation, the issue of whether the one or the other was right was unfortunately left undecided when NBC entered into a consent decree. Another clash between the two regulators has raised a doubt about the legality of network options on the time of affiliated stations. The Department has declared that this practice is in violation of the antitrust laws, but the FCC has held that option time is "reasonably necessary" to network operation and has refused to prohibit the practice. This issue also remains undecided.

The result of these conflicts has been to create some doubts about the correctness of the FCC's decisions and to lead to demands that it leave the regulation of competitive practices to the Department and the courts.

It's a Difficult Job

It is an old-fashioned American custom for people to run to the government when they want something or when they don't like what business men do. As a result, the FCC is under many pressures. In addition, it must always keep one eye upon a Congress which looks upon the Commission as its agent.

Because of the many-sided conflicts and controversies, the FCC cannot please everybody; try as hard as it does, there is always somebody with a complaint.

"When constabulary duty's to be done, The policeman's lot is not a happy one."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFIFTY YEARS OF THE DOC

February 1960 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56 -

Feature

FeatureHow Green Is Squaw Valley

February 1960 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureHow Public Is Music?

February 1960 By JAMES A. SYKES -

Feature

FeatureIndividuality in Forest Trees

February 1960 By F. HERBERT BORMANN -

Feature

FeatureA Pioneer in Electronics

February 1960 By J.B.F. -

Article

ArticleOur Mark Twain

February 1960 By STEARNS MORSE,

ELMER E. SMEAD

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLETTERS

April 1960 -

Books

BooksINTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

June 1939 By Elmer E. Smead -

Books

BooksTHE LIBERAL DEMOCRACY IN WORLD AFFAIRS: FOREIGN POLICY AND NATIONAL DEFENSE.

OCTOBER 1969 By ELMER E. SMEAD -

Books

BooksIDEOLOGIES AND UTOPIAS: THE IMPACT OF THE NEW DEAL ON AMERICAN THOUGHT.

JANUARY 1972 By ELMER E. Smead -

Books

BooksPRESSURE GROUPS ON THE LEGISLATURE OF NEW JERSEY

January 1939 By ELMER E. SMEAD, Harold G. Rugg '06

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE DEDICATION

DECEMBER 1962 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA.J. Liebling 1924

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureMICHAEL BRONSKI

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Feature

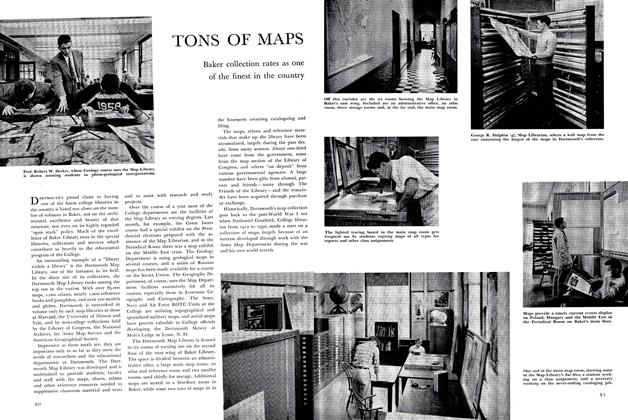

FeatureTONS OF MAPS

December 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureThe Lovinses and the Soft-Energy Path

JUNE 1982 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureAfter the Fire

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By Suzanne Spencer Rendahl ’93