A gray-haired member of the Magazine's new Editorial Boardreports on his fifth fall term.

What an experience it has been to take a sabbatical at Dartmouth and teach for three months! The view from behind the lectern offers an insider's perspective to the Dartmouth of today and gives a graying alumnus a feel for the place quite distinct from that of the nostalgic old grad in town paying more attention to classmates than to the scene around him.

I wasn't really prepared for the changes described in the catalogs and in talks at alumni gatherings, even though I had thought I was keeping in touch with Dartmouth better than most alumni. As a club or class or enrollment officer, I had been back on campus about once a year since graduation. But that's not like living there.

Step inside the Kresge Auditorium in the new Nelson A. Rockefeller Center for the Social Sciences, where the introductory course in policy studies is meeting to discuss Reaganomics, or Nelson Rockefeller's mistakes as governor of New York, or media ethics, or the arms race, or even how to get to the heart of a local zoning dispute. The 96 students in the course are a true cross-section of the campus large blocks from each class, men and women, blacks, whites, Orientals, Native Americans, foreign students.

Ask a question. You'll get a sea of hands, not the deadly silence that plagues classrooms at so many campuses. Even the freshmen speak up. Most of the time, the answers are right on target. Sometimes, responses spark a lively debate that dramatizes a point.

Assign a paper. Many students will take unusual approaches. At least one student will offer a unique solution. Ask students to work together in small committees and then monitor the progress of the group dynamics. Instead of mindlessly doing everything as a committee of the whole, the way so many committees try to do it in "real life," most of these Dartmouth students quickly figure out that the most efficient use of time is to divide the work, then bring back results before hammering out a final report.

Ask those committees to present their results both in oral and in written form, and today's Dartmouth students will go with strengths rather than ego trips. One person will do the oral presentation, another the writing, and a third will chair the preparation. (The Policy Studies faculty helps these unusually efficient committees to evolve by giving each committee member an identical grade. At grade-conscious Dartmouth, that's an important incentive, and the lesson lasts a lifetime.)

In short, Dartmouth remains a special place academically. The contrast with my teaching experiences at colleges elsewhere was startling. I'm not an academic; I'm a journalist. But as a journalist, I have had the opportunity to lecture elsewhere, and there's simply no comparison. The Dartmouth

students I taught were far better. Suffice it to say that our admissions screening process works. With rare exceptions, the survivors who become Dartmouth students are worthy of the name and probably more worthy than my classmates and I were.

I'd better explain how this all came about how an alumnus was able to spend a term teaching and auditing at Dartmouth because I suspect other readers of the Alumni Magazine could work out similar deals.

My newspaper, The Charlotte Observer, has a sabbatical program. It divides an academic year among four or five staff members who submit written proposals and make oral presentations. The program provides full pay and benefits throughout the sabbatical. So several years ago, I began talking with Dr. Gregory S. Prince Jr., then associate dean of the faculty and now vice provost, to work out a sabbatical at Dartmouth. Apparently, I was a first. My initial goal was to do some catching up in the basic medical sciences so I'd be better prepared, in my job as medical editor, to deal with the discoveries of the 1980s. In return, I offered to help Dartmouth in any way I could. I applied to The Observer for a sabbatical in the fall of 1983, and at Greg Prince's suggestion, applied for three months that coincided with the opening of the Rockefeller Center.

As part of the negotiations, I flew into Hanover to teach one of Prince's classes. He teaches contemporary American history, and as a former national editor of The Observer, I had had a catbird's view of the key events of 1970-1976, and could provide an unusual perspective. But I suppose it was also a test to be sure I didn't fall apart in the classroom.

My classmates were incredulous, even jealous, as word spread that I was going to spend a term at Dartmouth. I was to be treated as a visiting faculty member, though the precise title visiting scholar took a while to work out. But that was the key to a lovely faculty apartment at the corner of Park and Wheelock two bedrooms, a large living room, and a dining room ideal for entertaining.

I got to use a brand-new office on the second floor of the Rockefeller Center, overlooking Silsby. I could walk from my apartment to the office in less than ten minutes (a real advantage in parking-short Hanover). And the several routes I could take allowed me to stroll regularly by most of the buildings of the campus.

The fall of '83 was special indeed, preordained for a Southerner. Crisp mornings routinely contrasted with summer-like afternoons, and ultimate frisbee, usually a summertime sport, competed with football for space on the Green. There was even an out break of shorts in mid-November. And the fall colors lasted a long time.

In many ways, my fifth fall term on campus was similar to the other four several decades earlier. This time I went to all the home games. I went to the rallies and the bonfires just two these days though today's Dartmouth Night is vastly more elaborate than it used to be, with bands, and floats, and hoopla.

One major difference: no freshman hazing. Today, first-year students have virtually no duties to perform for upperclassmen except for building bonfires. No beanies, no tug-of-war, no

carrying furniture, no wetdown. Despite that, the Class of 1987 seemed as much on the road to lifelong fellowship as the classes of my era. The freshman trip is even more a part of their experience, as participation heads toward 100 percent.

I felt it was important to hold daily office hours and returned to the office each evening from 8 to 10 p.m. Students came in almost every night, to talk not only about policy studies, but also about careers, situations on campus, other courses. I became aware of problems facing each class, and of the fraternity system, and I was drawn into the ROTC debate. Being readily accessible to students added an invigorating dimension to my experience.

In a nutshell, policy studies is training in leadership and decision-making. The course looks at controversy and problem-solving from the community dispute to the international crisis. It's incredible how closely the dynamics of the arms race or the Falklands War resemble the local zoning dispute or the fight about a public nuisance.

The controversies all seem to begin with minor disagreements and escalate rapidly to the point where everything associated with the other side is evil. Remember the World War III rhetoric that erupted out of the shooting-down of the Korean airliner? That's a good illustration. So is World War I. Millions died because the shooting of an archduke by a fanatic led to a spiral of confrontation that seemed irreversible.

Policy studies looks at how to unravel those spirals. It teaches students to dig for the underlying problem as the first step in resolving a dispute.

In policy studies, students also analyze the techniques used to make policy decisions. The most usual method is called incremental: the leader makes the minimum possible decision, based on previous actions. This method is "safe" politically, because a wrong, small decision can be readily reversed. But over a period of years, this stepby-step process may establish a wrong course that is difficult to change. The pattern shows up in such diverse problems as strip zoning along a once-bucolic lane on the edge of a city, the arms race, or a war like the Falklands. Every decision may seem logical, defensible, and easy to implement. But the big picture may be badly flawed, and additional small steps may actually be making things worse.

There are alternatives to the incremental approach. Cost-benefit analysis has been popular in the past few decades, but it, too, may lead to policy decisions that are ineffective or that make things worse. System dynamics attempts to set up a model of the problems, but that model may be far from perfect and may require a wrenching change in direction.

The course readings were twofold core readings and case studies. The core readings set the foundation for the course; the case studies helped students to apply those basics to real-life problems.

Policy Studies 1 is taught by a group of faculty, with the program chairman, Prof. Doug Yates, calling the shots. In the fall term, the others included Prof. Frank Smallwood from government, Dr. David Bradley, a physician who has spent many years on the Tuck School faculty, Prof. Jonathan Brownell, a prominent lawyer, and me. Several others came in for single lectures.

How did I fit in to this? Journalists play a key role in implementing policy decisions, so when I talked about how the press worked, I was helping the students understand a dimension of the policy process. I told some tales about my role as a reporter and editor in policy decisions. I talked about the role of the press in general and of The Charlotte Observer in particular in the Pentagon Papers, Watergate, the Eagleton affair, and other national situations. I talked about journalistic ethics and truth, accuracy, impartiality, and fair play. It was a bit scary lecturing to a class of 96, but I managed it. I assigned papers, too. One paper was to be an analysis of the news columns of one of Dartmouth's four general-circulation newspapers, using the professional codes of ethics and "paying particular attention to standards of accuracy, impartiality and fair play." Presentations were to be done in pairs, with each of the pair getting the same grade. Many of the analyses were quite good, all the more impressive on a campus without journalism courses.

The Review didn't fare well. Most students who chose to analyze it found fault with accuracy, impartiality, and fair play, though they praised its independence (another ethical standard). Though many Dartmouth faculty and administrators have been upset with the Review for months, the students generally do read it. So it was interesting to see what happened when they applied real standards of journalism.

Those who studied The D found it generally lived up to those standards but said it was perhaps too timid and missed the mark on another ethical standard the responsiblity of newspapers to "discuss, question, and challenge actions and utterances of our government and of our public and private institutions."

Students criticized the paper's "lack of thoroughness," called for more "hard-nosed investigative reporting," said the paper had a "don't-rock-theboat mentality." Noted one team, "Rather than reporting a potentially explosive issue, the staff contents itself with covering an event after its importance has been established."

That's the kind of perception you'd expect from a journalist, not from a student paper that had to be written within 48 hours. But that's the quality of the Dartmouth student.

The folks at The D got the advantage of the more perceptive critiques, since I've been serving as an informal professional adviser to them for about three years. I made notes from the papers (no mention of names, of course) and read them at a D staff meeting.

The most challenging aspect of teaching is grading. Most papers in Policy Studies 1 were to be written in the style of articles or editorials, often with specific word limits, on the theory that most of today's newspapers offer political leaders the opportunity to argue for a particular policy within a set space on editorial pages. I may have been a rougher grader than some of the others. I certainly leaned hard on spelling, punctuation, and grammar, and I was outraged when errors were made in facts extracted from handouts.

During office hours, I had fun discussing with its authors why I graded a particular paper the way I did. It's a measure of the seriousness of today's graduate-school-bound students that every single grade is vital. Many come by to discuss grades, which means a Dartmouth faculty member must grade carefully and be prepared to defend the decision.

Our most challenging grading project involved videotaped presentations. Each student, individually this time, was asked to present a five-minute videotape on some aspect of arms-race policy or on what should be done with the Falklands. David Bradley, Jonathan Brownell, Kathy Schonberger, and I had the formidable task of grading 96 five-minute presentations that had been videotaped in the College's television studio. We gave separate grades for content and presentation.

Some students were human machine-guns on tape, spewing out words at barrel-burning rates; some had no sense of audience; some ran over the five-minute limit. But others had virtually professional presentations with props that emphasized their main points.

We averaged 24 minutes per tape in grading. Some took far longer. One of the machine guns, for instance, turned out to have a well-structured, carefully thought-out arms control paper that clearly was among the best in. the class. We had to play the tape again and again to pick up all the words. Naturally, we were tough with the presentation analysis, commenting that that kind of speed simply wouldn't work.

We could only grade these videotapes for five or at best six hours a day before becoming too exhausted to do a good job. We completed our course grades just minutes before the final deadline.

I was also involved in two other policy studies courses, teaching the middle third of a senior course called Ethical Issues in the Policy Process, run by Prof. Dana Meadows, and teaching a single class in Doug Yates's leadership seminar. In the first, I dealt in more depth with some of the media considerations what was news and what probably was not than I had time to do in Policy Studies 1.

What is ethical for one audience might not be for another. For instance, when the opposition party charged that a Southern gubernatorial candidate was gay, a story about that fact probably was required for newspapers in that state. But what real news value did the story have for readers outside the state, say as far away as New England? It was a subject of considerable discussion.

The Eagleton affair raised many of the same issues with a national constituency. In a nutshell, the Knight newspapers (of which The Observer, where I was then national editor, was a part) heard that Sen. Tom Eagleton just nominated for vice president had a history of mental illness. We dug out the facts. After confirming the story, we didn't publish it immediately but instead sent staffers to South Dakota to discuss it with Sen. George McGovern, the presidental nominee, and with Eagleton. That led directly to the spectacular announcement of Eagleton's history of mental illness.

When I outlined this case in some what more detail, several students thought we shouldn't have pursued the case at all. What business was it of ours? It was an interesting debate.

As luck would have it, McGovern campaigned at Dartmouth several days later. I asked him about his recollection. He said he had not known about the history of mental illness until Knight Newspapers reporters visited him. His first instinct, he said, had been to capitalize on the fact that millions of American families have members with mental problems. That meant standing behind Eagleton, who would be a martyr. Thus originated his famous 1,000 percent statement.

Then, he said, he started hearing from some of the most famous psychiatrists in the nation. Many told him the nation could not have Eagleton's particular mental illness manic-depressive disorder in the Oval Office. The danger could come in a manic state, the psychiatrists told him, because people in that state often think they can take over the world, and a president really can try to make that happen. So McGovern changed vice presidential candidates. My recounting the McGovern conversation made a nice sequel to the class discussion a few days before.

For the seniors, who were to work in groups of two to four, I offered a choice of assignments. They were to be members of a First Amendment committee at a constitutional convention charged with rewriting the amendment. One key problem to consider, I said, is whether the present First Amendment is defective because it doesn't take moral behavior into account. I mentioned sensational national tabloids, pornographic abuses, and journals of opinion that deliberately misstate facts.

"Or," I said, "you are the president of Dartmouth College, and you set improving the image of the College as a major goal. Write a policy for the Trustees setting out the role of the College administration with regard to media information, both within the College community and without."

"Or," I said, "you are the president of Dartmouth College, and you are deluged with comments and criticisms about The Dartmouth Review, from students, faculty, administrators, alumni, townspeople, and outsiders, all demanding that you do something about the Review. You are very much aware of First Amendment rights and traditional academic freedoms. What should you do?"

No one took the second choice, and only one brave bunch took on the First Amendment analysis. The majority of the groups analyzed the Review. The students were to separate facts, assumptions, values, etc., as they analyzed the situation. The process produced interesting lists of facts and a fair indication of how the Review is supported advertising plays a surprisingly minor role. There was concrete evidence that these students had dug hard and, though they knew little about journalism, done a first-class job. The other two ethical issues were

world hunger and Latin America what was happening and what shouldbe. Central America was particularly complex, since each country has a separate history, separate problems, and a separate role in the current political situation. The students realized they had to build a base of knowledge about Central America, so each small group took a different country and provided information for everybody.

The ethics class had a host of outside speakers, too. For instance, in my segment, I had folks come in from The D,The Valley News, the Dartmouth College News Service, and others. I even invited Andrew Merton, author of the famous 1979 Esquire article, "Hanging On (By a Jockstrap) To Tradition At Dartmouth." He ran into some tough questions from the class.

Dana Meadows brought in philosopher Bernard Gert to help with moral baselines and history professor Marysa Navarro to help us look at Central America. We saw propaganda films from both sides.

Teaching was just one aspect of my life in the new Rockefeller Center. Early on, I took on the role of newspaper resource for the center, clipping TheNew York Times and The BostonGlobe daily, and posting displays centered on particular current issues on the main bulletin board. The first and most obvious such issues were Lebanon and the war powers debate that came at the start of the term.

I pressed Frank Smallwood for a special program on Lebanon, and he brought it off. The speakers included Gene Garthwaite, professor of history, lan Lustick, associate professor of government, and Dr. George Harris, director of the Office of Analysis for the Near East and South Asia of the State Department. All three are experts on the Middle East.

I've spent a lot of time here talking about teaching at Dartmouth, but I also spent a good bit of my time as a student, in the audience at Kellogg Auditorium, learning about biochemistry from Prof. Henry Harbury. I couldn't actually "take" the course. I was permitted to audit the lectures (but not the discussion sections).

Biochemistry has become the real foundation for much of medicine and biology, and for the key developments of the 1980s, from breaking the genetic code to understanding how the body functions. In many ways, Harbury's lecture style resembles that of Francis Sears, the popular physics professor of my student days. Though Harbury goes very fast, he intersperses his lectures with demonstrations, including objects flying through the air; flashing lights and buzzers and bells are common. He spices even the driest topics with often-wry humor.

Today's introductory biochemistry is three full terms long, as the material to be covered has mushroomed. The part I took was primarily amino acids, proteins, and carbohydrates, with a smattering of immunology and genetics, both of which are now highly biochemical in nature.

At any rate, the class taught at the Dartmouth Medical School was a mixture of undergraduate biochemistry and chemistry majors, graduate chemistry students, virtually the entire firstyear class of the Dartmouth Medical School, and one gray-haired alumnus.

I observed many different styles of note-taking including a bunch who didn't take any. Instead, they were simply highlighting copies of lecture notes from previous years. Shades of the fraternity file drawers!

Besides teaching and being a student, I did get a chance to do some other things while I was in Hanover. Naturally, as I have indicated, I spent quite a bit of time down at Robinson Hall, talking with the editors of The D, and I also addressed the new staffers.

I also had the opportunity to make a number of other speeches. I presented my views on the ethics of my profession at the Institute for Applied and Professional Ethics, a relatively new program at Dartmouth. In fact, I was the first "outside" presenter at the institute. I spoke at a dinner meeting at the Faculty Club and then underwent the buzzsaw of questioning.

I should stress that there's no requirement for ethics in journalism, because there's no restriction of newspapering to professional journalists. The constitution says "Congress shall make no law," which means anyone can publish a newspaper, newsletter, or magazine under any auspices, for any purpose. Nonetheless, there are codes of ethics issued by the Society of Professional Journalists, Sigma Delta Chi, by the Associated Press Managing Editors, by the American Society of Newspaper Editors, and by the Radio-Television News Directors Association. It was on those codes, on books such as Playing It Straight, and, of course, on personal experience, that I based much of my discussions.

I also led a symposium on the latest in smoking research at the Dartmouth Medical School, spoke about investigative reporting to the staff of The ValleyNews, and discussed the news media with the Grafton County chapter of the New Hampshire Nurses Association.

Being on campus had other aspects, too. It meant swimming regularly in Alumni Gym. It meant running daily on several different routes so I passed virtually every building in Hanover. It meant sampling a variety of meals at different restaurants, both on campus and off.

It meant being two minutes from my seat at the football field. It meant being more deeply involved than ever in alumni affairs. But mostly, it just meant glowing in the fellowship of today's Dartmouth, and knowing that the Dartmouth of today is really not much different from the Dartmouth of long ago.

The visiting scholar takes a break in his Rockefeller Center office.

Scholar and student (Jenkins Marshall '84) address themselves to a paper.

My classmates were in-credulous•>, even jealous,as word spread that Iwas going to spend aterm at Dartmouth.

Ask a question. You'llget a sea of hands, notthe deadly silence thatplagues classrooms at somany campuses.

The Review didn't farewell. Most students whochose to analyze it foundfault with accuracy, im-partiality, and fair play.

I should stress thatthere's no requirementfor ethics in journalism.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryConsortium

April 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureCenters of Excellence and the Survival of Creativity

April 1984 By O. Ross Mclntyre '53 -

Feature

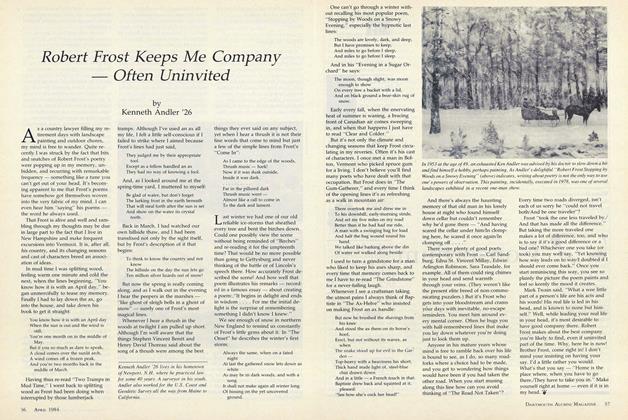

FeatureRobert Frost Keeps Me Company Often Uninvited

April 1984 By Kenneth Andler '26 -

Article

ArticleIt's Just Like Talking to People

April 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

April 1984 By William G. Long -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

April 1984 By Harry R. Zlokower

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryNAILS FROM DARTMOUTH HALL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureGISH

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

FeatureClassnotes

JAnuAry | FebruAry By DARTMOUTH COLLEGE LIBRARY -

Feature

FeatureCULTURAL CATALYSIS

December 1961 By DONALD BARTLETT '24 -

Feature

FeatureThayer School Report

April 1941 By F. H. Munkelt '08 (Thayer '09) -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWilliam Cook

OCTOBER 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87