Last year, educational institution from any other source of gifts. Alumni support Received more of it from their alumni than ow education's strongest financial rampart

WITHOUT THE DOLLARS that their alumni contribute each year, America's privately supported educational institutions would be in serious difficulty today. And the same would be true of the nation's publicly supported institutions, without the support of alumni in legislatures and elections at which appropriations or bond issues are at stake.

For the private institutions, the financial support received from individual alumni often means the difference between an adequate or superior faculty and one that is underpaid and understaffed; between a thriving scholar- ship program and virtually none at all; between well equipped laboratories and obsolete, crowded ones. For tax-supported institutions, which in growing numbers are turning to their alumni for direct financial support, such aid makes it possible to give scholarships, grant loans to needy students, build such buildings as student unions, and carry on research for which legislative appropriations do not provide.

To gain an idea of the scope of the support which alumni give—and of how much that is worthwhile in American education depends upon it—consider this statistic, unearthed in a current survey of 1,144 schools, junior colleges, colleges, and universities in the United States and Canada: in just twelve months, alumni gave their alma maters more than $199 million. They were the largest single source of gifts.

Nor was this the kind of support that is given once, perhaps as the result of a high-pressure fund drive, and never heard of again. Alumni tend to ,give funds regularly. In the past year, they contributed $45.5 million, on an annualgift basis, to the 1,144 institutions surveyed. To realize that much annual income from investments in blue-chip stocks, the institutions would have needed over 1.2 billion more dollars in endowment funds than they actually possessed.

ANNUAL ALUMNI GIVING is not a new phenomenon on the American educational scene (Yale alumni founded the first annual college fund in 1890, and Mount Hermon was the first independent secondary school to do so, in 1903). But not until fairly recently did annual giving become the main element in education's financial survival kit. The development was logical. Big endowments had been affected by inflation. Big private philanthropy, affected by the graduated income and inheritance taxes, was no longer able to do the job alone Yet, with the growth of science and technology and democratic concepts of education, educational budgets had to be increased to keep pace.

Twenty years before Yale's first alumni drive, a professor in New Haven foresaw the possibilities and looked into the minds of alumni everywhere:

"No graduate of the college," he said, "has ever paid in full what it cost the college to educate him. A part of the expense was borne by the funds given by former benefactors of the institution.

"A great many can never pay the debt. A very few can, in their turn, become munificent benefactors. There is a very large number, however, between these two, who can, and would cheerfully, give according to their ability in order that the college might hold the same relative position to future generations which it held to their own."

The first Yale alumni drive, seventy years ago, brought in $11,015. In 1959 alone, Yale's alumni gave more than $2 million. Not only at Yale, but at the hundreds of other institutions which have established annual alumni funds in the intervening years, the feeling of indebtedness and the concern for future generations which the Yale professor foresaw have spurred alumni to greater and greater efforts in this enterprise.

And MONEY FROM ALUMNI is a powerful magnet: it draws more. Not only have more than eighty business corporations, led in 1954 by General Electric, established the happy custom of matching, dollar for dollar, the gifts that their employees (and sometimes their employees' wives) give to their alma maters; alumni giving is also a measure applied by many business men and by philanthropic foundations in determining how productive their organizations' gifts to an educational institution are likely to be. Thus alumni giving, as Gordon K. Chalmers, the late president of Kenyon College, described it, is "the very rock on which all other giving must rest. Gifts from outside the family depend largely—sometimes wholly—on the degree of alumni support."

The "degree of alumni support" is gauged not by dollars alone. The percentage of alumni who are regular givers is also a key. And here the record is not as dazzling as the dollar figures imply.

Nationwide, only one in five alumni of colleges, universities, and prep schools gives to his annual alumni fund. The actual figure last year was 20.9 per cent. Allowing for the inevitable few who are disenchanted with their alma maters' cause,* and for those who spurn all fund solicitations, sometimes with heavy scorn, and for those whom legitimate reasons prevent from giving financial aid,§ the participation figure is still low.

WHY? Perhaps because the non-participants imagine their institutions to be adequately financed. (Virtually without exception, in both private and tax-supported institutions, this is—sadly—not so.) Perhaps because they believe their small gift—a dollar, or five, or ten—will be insignificant. (Again, most emphatically, not so. Multiply the 5,223,240 alumni who gave nothing to their alma maters last year by as little as one dollar each, and the figure still comes to thousands of additional scholarships for deserving students or substantial pay increases for thousands of teachers who may, at this moment, be debating whether they can afford to continue teaching next year.)

By raising the percentage of participation in alumni fund drives, alumni can materially improve their alma maters' standing. That dramatic increases in participation can be brought about, and quickly, is demonstrated by the case of Wofford College, a small institution in South Carolina. Until several years ago, Wofford received annual gifts from only 12 per cent of its 5,750 alumni. Then Roger Milliken, a textile manufacturer and a Wofford trustee, issued a challenge: for every percentage point increase over 12 per cent, he'd give $1,000. After the alumni were finished, Mr. Milliken cheerfully turned over a check for $62,000. Wofford's alumni had raised their participation in the annual fund to 74.4 per cent a new national record.

"It was a remarkable performance,' observed the American Alumni Council. "Its impact on Wofford will be felt for many years to come."

And what Wofford's alumni could do, your institution's alumni could probably do, too.

* Wrote one alumnus: "I see that Stanford is making great progress. However, I am opposed to progress in any form. Therefore I am not sending you any money."

A man in Memphis, Tennessee, regularly sent Baylor University a check signed "U.R. Stuck."

§ In her fund reply envelope, a Kansas alumna once sent, without comment, her household bills for the month.

Women's colleges, as a group, have had a unique problem in fund-raising—and they wish they knew how to solve it.

The loyalty of their alumnae in contributing money each year—an average of 41.2 per cent took part in 1959 is nearly double the national average for all universities, colleges, junior colleges, and privately supported secondary schools. But the size of the typical gift is often smaller than one might expect.

Why? The alumnae say that while husbands obviously place a high value on the products of the women's colleges, many underestimate the importance of giving women's colleges the same degree of support they accord their own alma maters. This, some guess, is a holdover from the days when higher education for women was regarded as a luxury, while higher education for men was considered a sine qua non for business and professional careers.

As a result, again considering the average, women's colleges must continue to cover much of their operating expense from tuition fees. Such fees are generally higher than those charged by men's or coeducational institutions, and the women's colleges are worried about the social and intellectual implications of this fact. They have no desire to be the province solely of children of the well-to-do; higher education for women is no longer a luxury to be reserved to those who can pay heavy fees.

Since contributions to education appear to be one area of family budgets still controlled largely by men, the alumnae hope that husbands will take serious note of the women's colleges' claim to a larger share of it. They may be starting to do so: from 1958 to 1959, the average gift to women's colleges rose 22.4 per cent. But it still trails the average gift to men's colleges, private universities, and professional schools.

memo: from Wives to Husbands

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe TPC Planning Program

April 1960 By FRANK SMALLWOOD '51 -

Feature

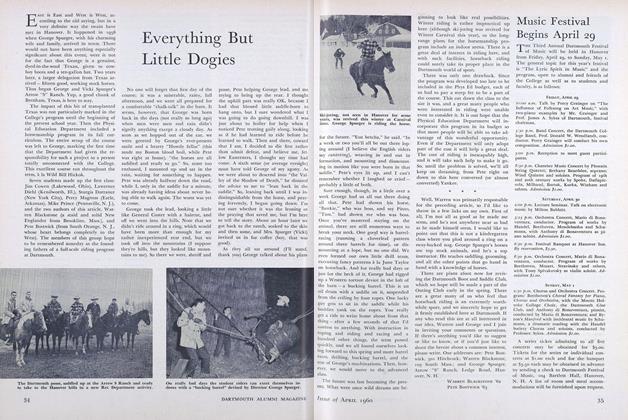

FeatureEverything But Little Dogies

April 1960 By WARREN BLACKSTONE '62, PETE BOSTWICK '63 -

Feature

FeatureTHE ALUMNUS/A

April 1960 -

Article

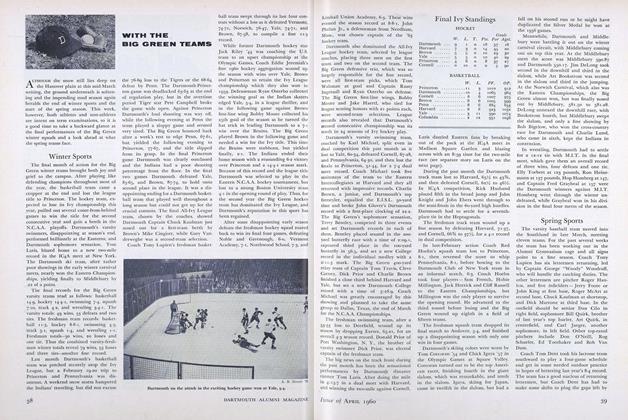

ArticleWinter Sports

April 1960 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

April 1960 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1951

April 1960 By LOYE W. MILLER, JAMES V. ROBINSON