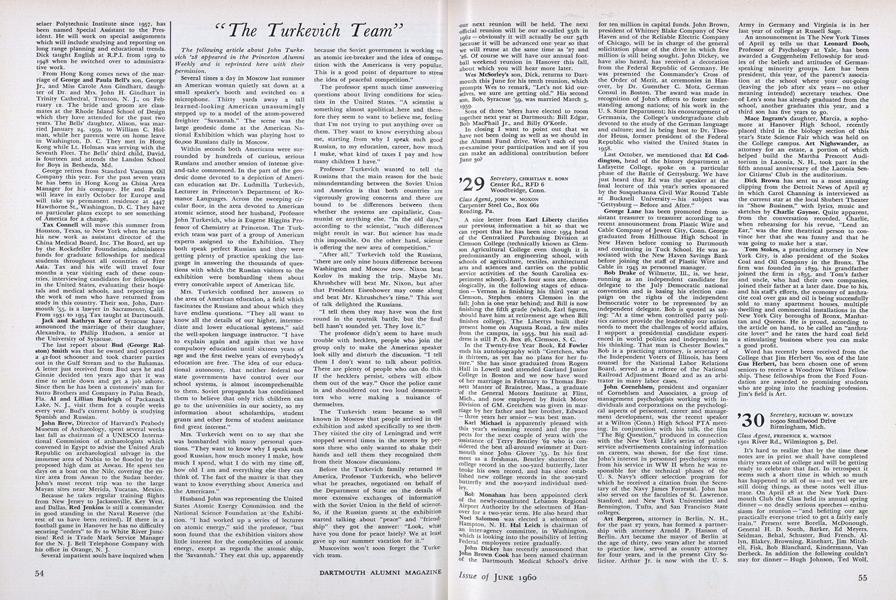

The following article about John Turkevich '28 appeared in the Princeton AlumniWeekly and is reprinted here with theirpermission.

Several times a day in Moscow last summer an American woman quietly sat down at a small speaker's booth and switched on a microphone. Thirty yards away a tall learned-looking American unassumingly stepped up to a model of the atom-powered freighter "Savannah." The scene was the large geodesic dome at the American National Exhibition which was playing host to 60,000 Russians daily in Moscow.

Within seconds both Americans were surrounded by hundreds of curious, serious Russians and another session of intense giveand-take commenced. In the part of the geodesic dome devoted to a depiction of American education sat Dr. Ludmilla Turkevich, Lecturer in Princeton's Department of Romance Languages. Across the sweeping circular floor, in the area devoted to American atomic science, stood her husband, Professor John Turkevich, who is Eugene Higgins Professor of Chemistry at Princeton. The Turkevich team was part of a group of American experts assigned to the Exhibition. They both speak perfect Russian and they were getting plenty of practice speaking the language in answering the thousands of questions with which the Russian visitors to the exhibition were bombarding them about every conceivable aspect of American life.

Mrs. Turkevich confined her answers to the area of American education, a field which fascinates the Russians and about which they have endless questions. "They all want to know all the details of our higher, intermediate and lower educational systems," said the well-spoken language instructor. "I have to explain again and again that we have compulsory education until sixteen years of age and the first twelve years of everybody's education are free. The idea of our educational autonomy, that neither federal nor state governments have control over our school systems, is almost incomprehensible to them. Soviet propaganda has conditioned them to believe that only rich children can go to the universities in our society, so my information about scholarships, student grants and other forms of student assistance find great interest."

Mrs. Turkevich went on to say that she was bombarded with many personal questions. "They want to know why I speak such good Russian, how much money I make, how much I spend, what I do with my time off, how old I am and everything else they can think of. The fact of the matter is that they want to know everything about America and the Americans."

Husband John was representing the United States Atomic Energy Commission and the National Science Foundation at the Exhibition. "I had worked up a series of lectures on atomic energy," said the professor, "but soon found that the exhibition visitors show little interest for the complexities of atomic energy, except as regards the atomic ship, the 'Savannah.' They eat this up, apparently because the Soviet government is working on an atomic ice-breaker and the idea of competition with the Americans is very popular. This is a good point of departure to stress the idea of peaceful competition."

The professor spent much time answering questions about living conditions for scientists in the United States. "A scientist is something almost apolitical here and therefore they seem to want to believe me, feeling that I'm not trying to put anything over on them. They want to know everything about me, starting from why I speak such good Russian, to my education, career, how much I make, what kind of taxes I pay and how many children I have."

Professor Turkevich wanted to tell the Russians that the main reason for the basic misunderstanding between the Soviet Union and America is that both countries are vigorously growing concerns and there are bound to be differences between them whether the systems are capitalistic, Communist or anything else. "In the old days," according to the scientist, "such differences might result in war. But science has made this impossible. On the other hand, science is offering the new area of competition."

"After all," Turkevich told the Russians, "there are only nine hours difference between Washington and Moscow now. Nixon beat Kozlov in making the trip. Maybe Mr. Khrushchev will beat Mr. Nixon, but after that President Eisenhower may come along and beat Mr. Khrushchev's time." This sort of talk delighted the Russians.

"I tell them they may have won the first round in the sputnik battle, but the final bell hasn't sounded yet. They love it."

The professor didn't seem to have much trouble with hecklers, people who join the group only to make the American speaker look silly and disturb the discussion. "I tell them I don't want to talk about politics. There are plenty of people who can do this. If the hecklers persist, others will elbow them out of the way." Once the police came in and shouldered out two loud demonstra- tors who were making a nuisance of themselves.

The Turkevich team became so well known in Moscow that people arrived in the exhibition and asked specifically to see them. They visited the city of Leningrad and were stopped several times in the streets by persons there who only wanted to shake their hands and tell them they recognized them from their Moscow discussions.

Before the Turkevich family returned to America, Professor Turkevich, who believes what he preaches, negotiated on behalf of the Department of State on the details of more extensive exchanges of information with the Soviet Union in the field of science. So, if the Russian guests at the exhibition started talking about "peace" and "friendship" they got the answer: "Look, what have you done for peace lately? We at least gave up our summer vacation for it."

Muscovites won't soon forget the Turkevich team.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE TREASURER'S REPORT

December, 1914 -

Article

ArticleTrio Leave Service

December 1945 -

Article

ArticleReynolds Scholarships

May 1975 -

Article

ArticleDon't Lose the Extras That Make Dartmouth What It Is

APRIL 1992 -

Article

ArticleNebraska

DEC. 1977 By ED REHUREK ’44 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1948 By HERBERT F. WEST '22