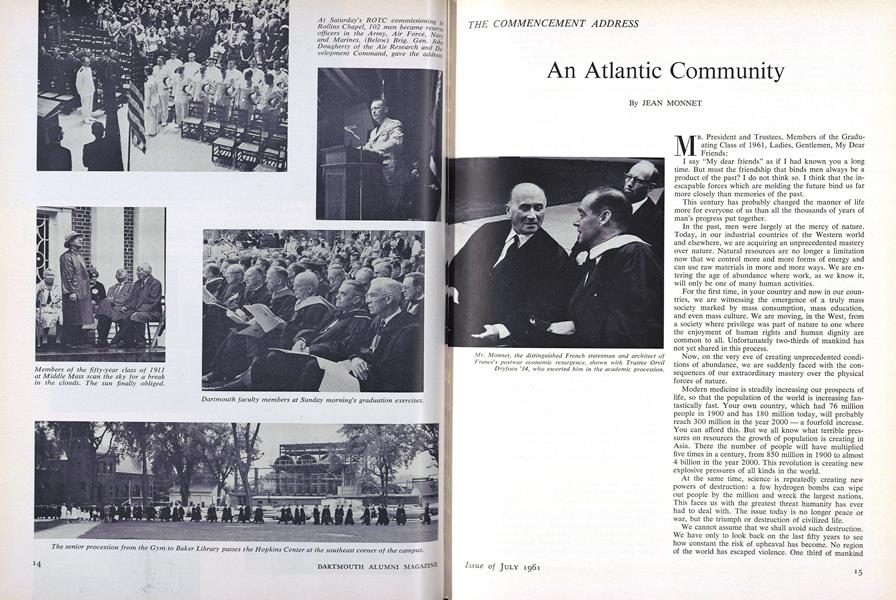

THE COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

MR. President and Trustees, Members of the Graduating Class of 1961, Ladies, Gentlemen, My Dear Friends:

I say "My dear friends" as if I had known you a long time. But must the friendship that binds men always be a product of the past? I do not think so. I think that the inescapable forces which are molding the future bind us far more closely than memories of the past.

This century has probably changed the manner of life more for everyone of us than all the thousands of years of man's progress put together.

In the past, men were largely at the mercy of nature. Today, in our industrial countries of the Western world and elsewhere, we are acquiring an unprecedented mastery over nature. Natural resources are no longer a limitation now that we control more and more forms of energy and can use raw materials in more and more ways. We are entering the age of abundance where work, as we know it, will only be one of many human activities.

For the first time, in your country and now in our countries, we are witnessing the emergence of a truly mass society marked by mass consumption, mass education, and even mass culture. We are moving, in the West, from a society where privilege was part of nature to one where the enjoyment of human rights and human dignity are common to all. Unfortunately two-thirds of mankind has not yet shared in this process.

Now, on the very eve of creating unprecedented conditions of abundance, we are suddenly faced with the consequences of our extraordinary mastery over the physical forces of nature.

Modern medicine is steadily increasing our prospects of life, so that the population of the world is increasing fantastically fast. Your own country, which had 76 million people in 1900 and has 180 million today, will probably reach 300 million in the year 2000 - a fourfold increase. You can afford this. But we all know what terrible pressures on resources the growth of population is creating in Asia. There the number of people will have multiplied five times in a century, from 850 million in 1900 to almost 4 billion in the year 2000. This revolution is creating new explosive pressures of all kinds in the world.

At the same time, science is repeatedly creating new powers of destruction: a few hydrogen bombs can wipe out people by the million and wreck the largest nations. This faces us with the greatest threat humanity has ever had to deal with. The issue today is no longer peace or war, but the triumph or destruction of civilized life.

We cannot assume that we shall avoid such destruction. We have only to look back on the last fifty years to see how constant the risk of upheaval has become. No region of the world has escaped violence. One third of mankind has become Communist, another third has obtained independence from colonialism, and even among the remaining third, nearly all countries have undergone revolutions or wars.

True, atomic bombs have made nuclear war so catastrophic that I am convinced no country wishes to resort to it. But I am equally convinced that we are at the mercy of an error of judgment or a technical breakdown the source of which no man may ever know.

In short, if men are beginning to dominate nature, their control over their political relations between themselves has failed to progress with the needs of the times. Men are gradually freeing themselves from outside controls and in the process are learning that, henceforth, their main problem is to accept the responsibility to control themselves.

So, my friends, you may either enjoy the extraordinary privilege of having long years before you of a marvellous future in a world that your elders could never have hoped for, or the terrible prospect of witnessing the end of civilized society.

You will be able to play a part in settling this issue. On your contribution and that of those who, like you, in all the countries of the earth are entering on a new life depends the outcome for yourselves, for mankind and for the whole of civilization.

In this connection, I would like to pay a warm tribute to your President, John Dickey, for having instituted the Great Issues Course which can greatly help to prepare you for the major decisions you will have to face in the years to come.

THE main facts that emerge from what I have just said are that we are in a world of rapid change, in which men must learn to control themselves in their relations with others. To my mind, this can only be done through institutions. Human nature does not change, but when people accept the same rules and the same institutions to make sure that they are applied, their behavior towards each other changes. This is the process of civilization itself.

You yourselves know the importance of institutions from your own history. The thirteen states would not have won the War of Independence had they tried to fight it separately. After the war, the Confederation was only a few years old when you found it necessary to draft a federal constitution to keep the Union together and make it effective.

Since the war, we in Europe have also learned the need of common institutions. After the war, it seemed the nations of Europe might be doomed to irretrievable decline. With Germany still occupied, everyone was in doubt as to the future relations between victors and vanquished. Had the traditional relations between France and Germany been maintained, their desire to dominate each other would have led to new disasters. Had either, driven by mistrust of her neighbor, been tempted to veer between East and West, that would have been the end of the free nations in Europe, and in consequence, of the West.

You must realize that we in Europe have had, and still have, a far greater problem than you. For when you began you were basically the same people, with the same language and the same traditions; and you had just fought together in the common cause of independence. Europe, on the other hand, is made up of separate nations with different traditions, different languages and different civilization and the nation states have behind them a long past of mutual rivalries and attempts at domination.

Your people created institutions while they were all citizens of one nation. We in Europe are engaged in the process of creating common institutions between states and people which have been opposed to each other for centuries.

What a contrast their history makes with the way you have grown in the last 170 years! Under your federal institutions, you have been able to develop the most industrialized society in the world; and to assimilate people from all the nations of Europe in that society and give them high and constantly growing standards of living. Thus your continent has become a nation. During the same years, the European nations have developed their highly industrialized societies separately and often against one another, each nation producing deeply rooted national administrations. Common institutions were the only way to overcome these profound factors of divisions and give Europe the same chances of harmonious development America had.

It is for these reasons that in 1950, when France decided to transform its relations with Germany, it proposed to pool what were then the two countries' basic resources, coal and steel, under common institutions open to any other free European countries willing to join them.

While the Coal and Steel Community in itself was a technical step, its new procedures, under common institutions, created a silent revolution in men's minds. France and Germany, in particular, have been reconciled after three great wars, in 1870, in 1914, and again in 1940. Think of the extraordinary change shown by the fact that today, at French invitation, German troops train on French soil.

So, the progress towards unity is steadily gathering way. The Coal and Steel Community has made possible EURATOM, the Common Market, and economic union; now economic union, in turn, creates the demand for a political union and a common currency.

Today, a uniting Europe can look to the future with renewed confidence. The Common Market with 170 million people - and if, as I hope and believe, Britain and other countries soon join it, it will number greatly over 200 million - commands resources that are comparable to those of America and Russia. Europe today has the prospect of becoming, with the United States, Russia and China, one of the great forces fashioning tomorrow's world.

What is the lesson of these successes—first your success in building up the United States of America with consequences which have changed world history; and now, Europe's success in wresting a new future from a prospect which, at the end of the war, was as depressing as that of the Greek city states in decline?

The lesson, I think, is the extraordinary transforming power of common institutions.

Almost every time, since the war, that the countries of the West have tried to settle their problems separately, they have suffered reverses. But when they have moved together, they have opened up new opportunities for themselves.

The reason for this is that today all our major problems go beyond national frontiers. The issues raised by nuclear weapons, the underdeveloped areas, the monetary stability of our countries and even their trade policies, all require joint action by the West. What is necessary is to move towards a true Atlantic Community in which common institutions will be increasingly developed to meet common problems.

We must, naturally, move step by step towards such an immense objective. The pioneer work has already been undertaken by the unification of Europe. It is already creating the necessary ferment of change in the West as a whole.

Britain is gradually coming to the conclusion that it should join the general movement towards European unity and the Common Market. As for your country, the prospect of a strong, united Europe emerging in Europe from the traditional divisions of the Continent has convinced it that a partnership between Europe and the United States is necessary and possible. The United States is already using the new Atlantic economic organization, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, of which it is a member along with Canada and the European nations.

That we have begun to cooperate on these affairs at the Atlantic level is a great step forward. It is evident that we must soon go a good deal further towards an Atlantic Community.

The creation of a united Europe brings this nearer by making it possible for America and Europe to act as partners on an equal footing. I am convinced that ultimately the United States too will have to delegate powers of effective action to common institutions, even on political questions.

Just as the United States in their own days found it necessary to unite, just as Europe is now in the process of uniting, so the West must move towards some kind of union. This is not an end in itself. It is the beginning on the road to the more orderly world we must have in order to escape destruction. The partnership of Europe and the United States should create a new force for peace.

It will give the West the opportunity to deal on a new basis with the problems of the underdeveloped areas. For, just as our own societies would never have found their spiritual and political equilibrium if the internal problems of poverty had not been tackled, so the liberties which form the best part of the Western tradition could hardly survive a failure to overcome the international divisions between rich and poor, and between black, yellow and white.

A partnership of Europe and America would also make it possible to overcome the differences between East and West. For what is the Soviet objective? It is to achieve a Communist world as Mr. Khrushchev has told us many times. When this becomes so obviously impossible that nobody, even within a closed society, can any longer believe it, then Mr. Khrushchev or his successor will accept facts. The conditions will at last exist for turning so-called peaceful coexistence into genuine peace. At that time, real disarmament will become possible.

I believe that the crucial step is to make clear that the West is determined not only to complete the unification process, but also to build firmly the institutional foundation of that unity. As this determination appears clearly then the world will react to the trend. We must therefore take the first steps quickly.

In the past, there has been no middle ground between the jungle law of nations, and the Utopia of international concord. Today, the methods of unification developed in Europe show the way. As we can see from American and British reactions to European unity, one change on the road to collective responsibility brings another. The chain reaction has only begun. We are starting a process of continuous reform which can alter tomorrow's world more lastingly than the principles of revolution so widespread outside the West.

Naturally, progress will not go without danger; no great change is effected without effort and setbacks. In Europe, the movement to unity has overcome many such troubles and, in my opinion, is already irreversible.

In this connection, I would like to leave you by telling the story of a statesman who was once asked the secret of his success. He replied that in his youth he had met God in the desert and that God had revealed to him the attitude that was essential to any great achievement. What God had said was this: "To me all things are means to my end - even the obstacles."

Mr. Monnet, the distinguished French statesman and architect ofFrance's postwar economic resurgence, shown with Trustee OrvilDryfoos '34, who escorted him in the academic procession.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Global Classroom

Sept/Oct 2004 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Feature

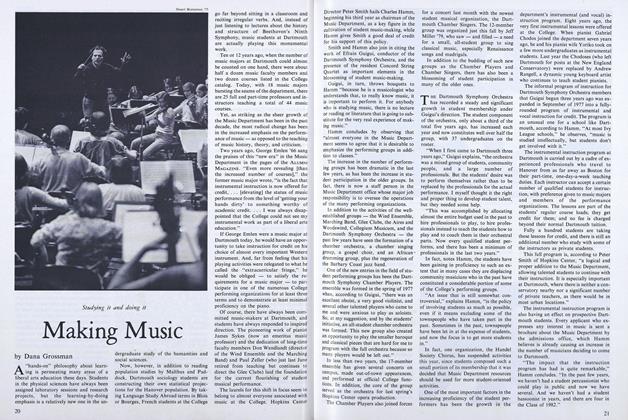

FeatureMaking Music

November 1978 By Dana Grossman -

Feature

FeatureTHE CREATIVE ARTS

May 1954 By IRWIN ED MAN -

Feature

FeatureStage Director at the Met

February 1962 By RAYMOND J. BUCK '52 -

Cover Story

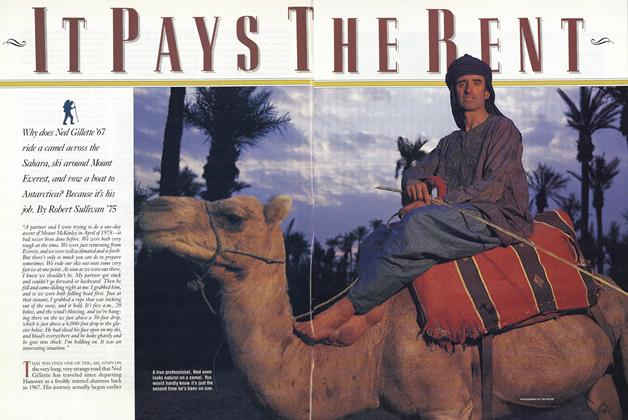

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHer Type

MARCH 1995 By Susan Ackerman '80