A T THE VVHITE-SPIRED CHURCH in Lower Waterford, Vermont, cars crept in off the interstate an hour and a half before the service began. It was a brilliant fall day with clear blue skies and, all around, the pulsing embers of a fiery October. On his knees in the warming stin, an old man painted white lines in the street with bucket and brush, a detail that would not have gone unnoticed by the man these people had come to honor. He would have stopped to" talk and later, perhaps, he would have written it down, about the man w ho still did it the old way. People emerged from their ears and some entered the church clinching worn copies of his first editions. Elsewhere his name might not be known, but up here in the North (Country he's know n as the man w ho wrote the book.

Inside, as the church gradually tilled, a gray-haired worked the piano and brought forth his favorites: "Swing Lo, Sweet Chariot," "Onward Christian Soldiers," a surprising selection for a man of the woods. Or was it? In the front pew tour writers with various ties to the man sat together, their fingers marking the pages of the books from which they would read: Fighting Yankee; Tall Trees. Tough Men; Drama on the Connecticut; Spiked Boots.

The service was a celebration in words, mostly the words of this man who grew to manhood a short distance from this is church, a place long since underwater. water, a place accessible nly through the memory of the remaining few who once lived there and through what has been written about those days, before a highway to send logs on their Way south to cities unimaginable to the young men who harvested the trees.

In this church, on this afternoon, his wods were read, a literary festiveity perhaps unlike any that had ever happened in this faraway place, faraway at least from places where we expect to hear readings of the written word, certainly of words written in just this way.

The attic was just like that of any other North Country farmhouse cobwebby rafters from which hung mysterious bags, braided traces of corn, and old clothes...and then, suspended from a nail, two pair of rivennen's boots.

The two-inch calks were sharp as needles and looked like-new. The leather had been recently oiled and shone dully in the sunlight that filtered through the dnsty windows.

"Ice going out?" I joked, "I set you've your boots greased."

I 'cm tamed from tossing in-the.-way objects aside and stalked over to the boors.. .Hi took them in ome huge hand and held them almost tenderly.

"These boots, young feller," he said, "may be said to mark the passing of an era...Every Spring I take these boots out and file off the runst and grease 'em. And I Know I'll never use them again. Not ever...When I was polishing up these old boots the last time, I got to thinking about the last long-log river drive down the Connecticut, and how I wished someone could write it up so's it would be remembered."

The man who wrote it up so's it would be,remembered was Robert Everdmg Pike '25, known to his fans as Bob Pike, and the book was Spiked Boots, the farmous North Country compilation of stories and legends of loggers, river drivers, and rascals.

Pike, who earned his doctorate in foreign languages from Harvard and maintained a career as professor of foreign languages at MonmouthJunior College in New Jersey, grew up on a farm in Upper Waterford, Vermont. The farm was set alongside the Connecticut River,-just above Fifteen Mile Falls, where his early companions were the men who rode the logs down the river in the spring, spiked boots on their feet. These men, whose names were such as 'Phonse Robe}7, Dan Bossy, Vern Davison, were legends—hard- drinking, lumber-riding cowboys who lived in die woods and worked the livers when the water was high and tossed car-sized logs about with picks and peaveys when the water was low In the evenings, in their camps, they told stories. Like this one.

The water was high and fan, of course. Below one rollway was an eddy that kept the logs inshore instead of letting them float down with the current. They got piled up pretty deep there, so I told the men to wait while I took two mat and went down to pole them out into the river.

We were working away and had got them pretty well cleared out. when there came-a yell from the men on the bank. We looked up and there all the logs on that railway had got looser and werestafthig to roll down on top of its. We turned and ran over the floating logs for the middle of the river. The other two men made it safely but I didn't.

My first jump. Handed on my left foot on the big spruce but before I could bring up my right foot, another log bobbed out of the 'water awl caught it between the two logs. I stuck my peavey 'into the log and pulled for all I was-worth but I was stuck there as if I was in a bear trap. I caught a glimpse of those logs just lea ping over the bank and knew my time had come and by God, mister, it would have come, right there and then, if pretty near a miracle hadn't happened.

There was a rivemian nanied Dan Bossy working up on that rollway. Dan was the best man on logs I ever saw in my life, I've seen him do things I'd never have believed if I hadn't seen' 'em myself. Well. he seen what a fix I was in, and even before the logs came thundering down off the skids, he run out and jumped 15 feet straight down and landed on that log behind me and drove one end of it deep into the water. The other end snapped'up past my head like a flash oflight....

My foot was free then and I sailed out of there on my other log as quick and easy as if I were on a feather-bed. And not one second later that rollway landed kerplunk where 1 had been standing and filled the river ten feet deep with logs. Bossy? He was right behind me, on that same big spruce.

Pike claimed to have learned to read in the local library that doubled as a bar. He carried these stories with him in his head, though his life took him to vastly different places, most notably, Eatontown, a busy town on the New Jersey shore, where he lived for most of his adult life.

In 1955 Pike wrote the stones down and put them together into a book. He sent the manuscript to Little, Brown. They rejected it. noting that the writing had "considerable flair" but that the book as a whole "lacked dramatic cohesion." Undeterred, he took the manuscript up to St. Johnsbury. Vermont, to the Cowles Press, where he ordered a print run of 500 copies. When it came off the presses, brightly bound in red canvas, he loaded the books into the trunk of his car and drove north. When he got to Colebrook, New Hampshire, he saw a familiar-looking man crossing the street. Pike stopped the car, The man turned out to be the son of a famous river driver. Pike look a Copy, of the book out of the trunk and gave it to the young.man, saying, "This book is about your father. "That night when Pike checked into the hotel in town, the man at the desk was standing there reading the very same copy of Spiked Boots that Pike had given out that morning. And so Pike asked him how he liked the book and the man said, "Oh! This is a hell of a good book," and Pike said, "I wrote it." And ever since then, up in those parts, Bob Pike has been known as the man who wrote the book.

It was. actually the first of several books that. Bob Pike wrote and published himself. Laughter and Tears., a somewhat sobering, somewhat hilarious collection of photos of interesting gravestones and epitaphs, came in 1971 in an edition of 1,000. In 1975 he published Drama on the Connecticut, again printing an even 1,000. In 1967, WAV Norton published Tall Trees, Tough Men, a rework of Spiked Boots and the first and only of Pike's books to gain bookstore recognition. It remains in print: A copy of Spiked Boots, if it can be found in antiquarian book circles, would cost $100.

All this from a man who spoke fluent Latin, French, Italian, Spanish, German, and Russian and who made his career in academia. In 1982 Pike wrote a long-letter to Dartmouth, "to aid in composing my obituary The last paragraph reads thus: "My favorite winter vacation spot is in the Island of Martinique. I am not in favor of girls at Dartmouth. J read line print and drive a car without glasses. .My father chewed tobacco; 1 eschew it. He voted the Democratic ticker. I vote Republican, although I actually expect they are equally reprehensible. I run one mile every other day because it. gives me the pleasant illusion that I am not dead yet. My favorite authors arc Jack Anderson and Ann Landers. [ drive an old Cadillac and an older Oldsmobile, both paid for. I shudder to read in The New York Times such horrors as: 'in some counties of New Jersey someone called the Voting Register totals the votes,' or in 'The Christian Science Monitor,-the word horefrost, or in the Wall Street Journal, of an 'excruciating agony.'"

What he failed to mention were his fans, of which there are many, of surprising variety. After all the words had been read that day of Robert Pike's memorial service, the people who had come in his honor gathered in the big room in the basement of the church amidst cider and homemade donuts. In the crowd a young man carried a copy of Spiked Boots against his chest. A woman spotted the beautiful old book, held so lovingly. "I see you brought the book," she said. The book's faded red canvas cover had been fortified by a layer of floral shelf paper. "Yup," he said and he opened the book. Some of the well-read pages fell lose from the binding. The inside coyer was scattered with signatures of Bob Pike and the man smothered them with his big rough hand. "Every time he came up here, I had him sign it all over again."

Pike was a life-long Christian Scientist and he had never suffered any illness. He died in his sleep on August? in his New Jersey home. He was 92. The farm where he grew up in Upper Waterford had long since been inundated by water backing up from the Moore Dam. But his heart and soul remain there. Every summer he visited his home place, and in his New Jersey refrigerator he kept an open pitcher of maple syrup. In his possession was a panoramic photograph of the village of Upper waterford, before it went under. Of the photo, he wrote, "In it, you see very clearly almost every building in the village the Pike place (where the boat launch is now), the Pike Tavern (also the library), my one-room white schoolhouse, the Congo church, the cemetery, now removed with its contents, to just below the Moore Dam, where my own stone is patiently waiting for me."

When his second wife, the beautiful Parisian dancer Helene, died in 1983, Pike had his stone set next to hers in the Waterford 'Cemetery, just 150 feet from the Connecticut River. At that time he wrote an epitaph for her so long that his adoring words cover the stone. Then he wrote one for himself, considerably shorter, and had it cut into the stone, missing only the date of his death. It makes no mention of his academic accomplishments. Instead, it identifies him as the author of Spiked Boots. The man who wrote the book, home at last, as quick and easy as if he had floated there on the river of his childhood.

The passing of Robert Pike '25 got people talking again about the dangerous, romantic work . that used to flow past the College every spring.

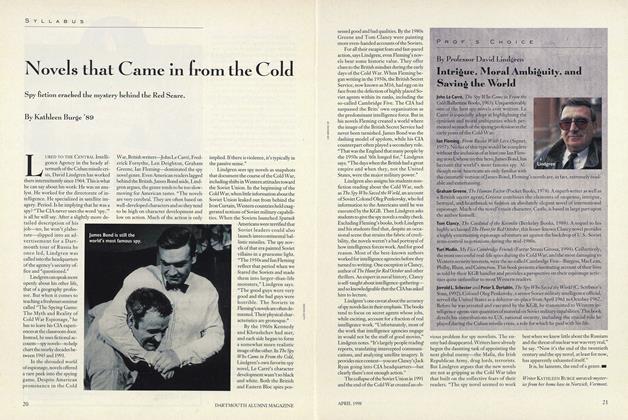

Pike struck a pose in Paris the summer after he graduated from Dartmouth. But there—and in longer stops that followed in Cambridge and New Jersey—he kept the stories of his northern Vermont boyhood close to heart.

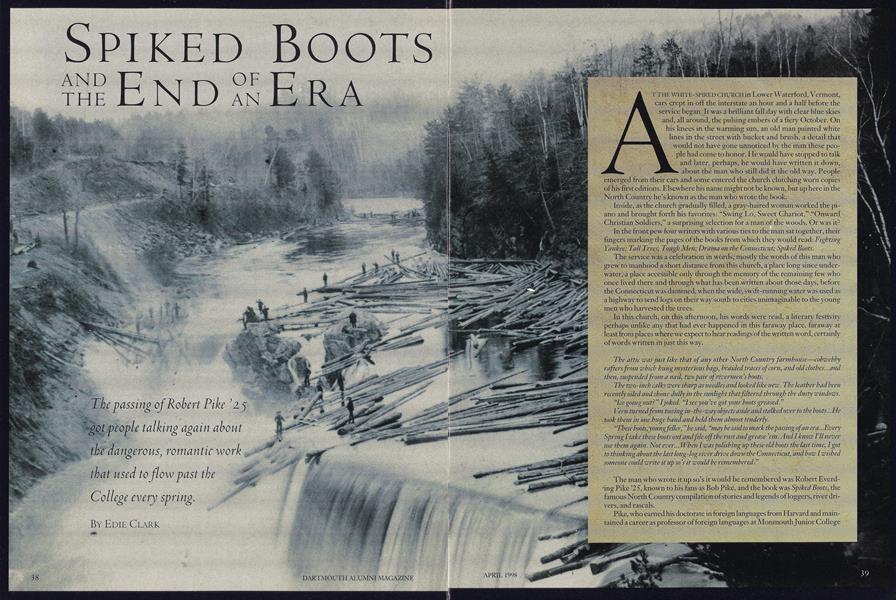

"The old covered Ledyard bridge at Hanover," wrote Pike, "beloved by so many Dartmouth students, sturdily withstood all the attacks of the rivermen, though a great many jams piled up behind it" (above). North of Hanover narrowness created other problems (preceding pages). The last Connecticut River drive went south in the spring of 1915.

EDIE CLARK wrote a five-part series on the Connecticut River for Yankee in the 1980s. The author of the memoir The Place He Made, she just completed a residency at the MacDowell Colony.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Trembling Edge Of Science

April 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureA Change in the Weather

April 1998 -

Feature

FeatureThe STREAMLINER DINER

April 1998 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Article

ArticleThe Benefits of a College Town

April 1998 By Jeanhee Kim '90 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

April 1998 By John MacManus -

Article

ArticleNovels that Came in from the Cold

April 1998 By Kathleen Burge '89

Features

-

Feature

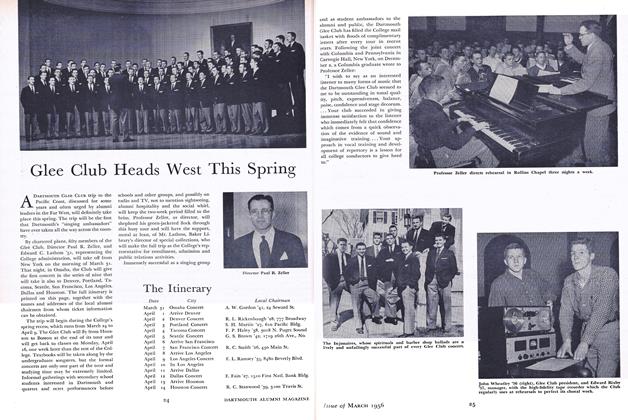

FeatureGlee Club Heads West This Spring

March 1956 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SKIWAY

January 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

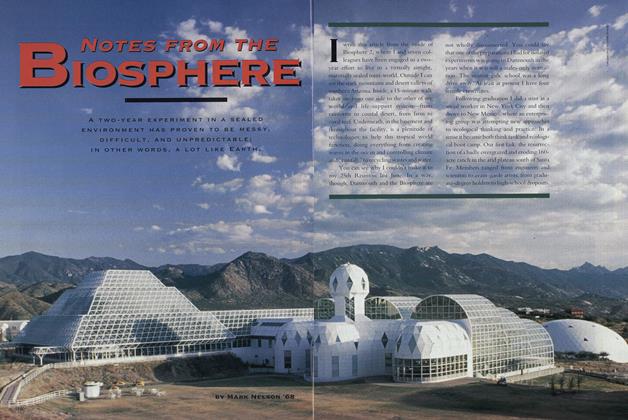

FeatureNotes from the Biosphere

October 1993 By Mark Nelson '68 -

Feature

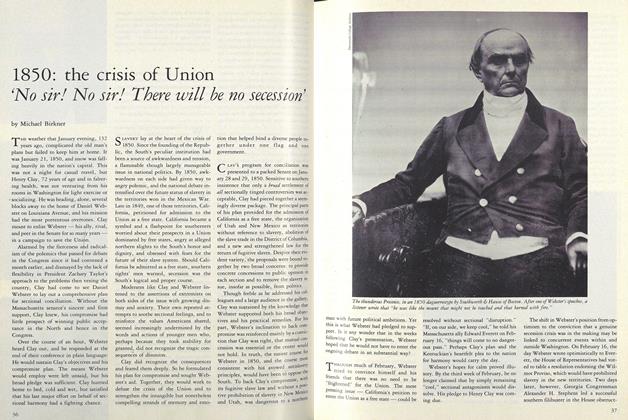

Feature1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

MARCH 1982 By Michael Birkner -

Feature

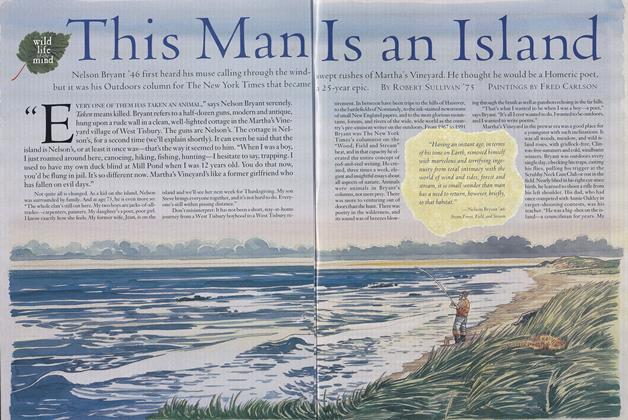

FeatureThis Man Is an Island

OCTOBER 1996 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

FEATURE

FEATUREIdeal Exposure

MAY | JUNE 2019 By STEVE GLEYDURA