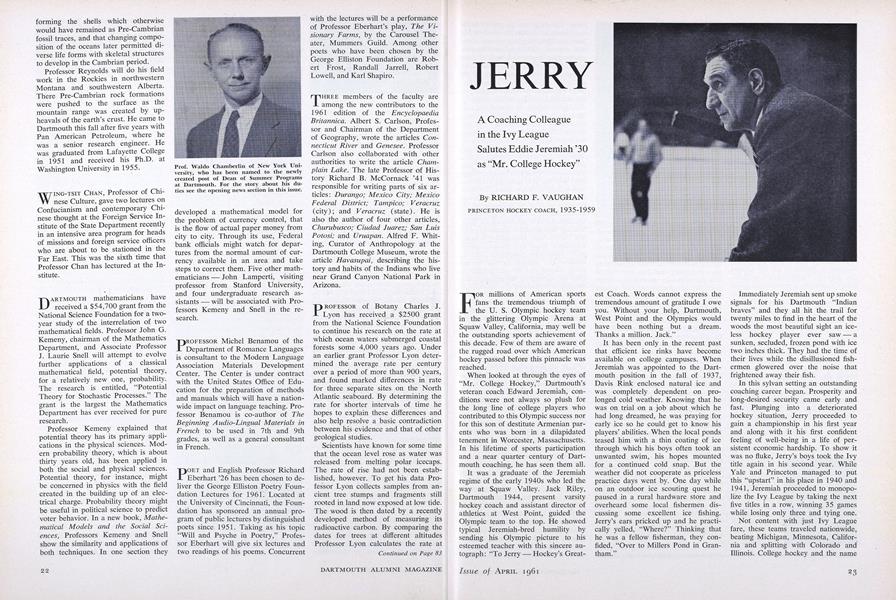

A Coaching Colleague in the Ivy League Salutes Eddie Jeremiah '30 as "Mr. College Hockey"

PRINCETON HOCKEY COACH, 1935-1959

FOR millions of American sports fans the tremendous triumph of the U. S. Olympic hockey team in the glittering Olympic Arena at Squaw Valley, California, may well be the outstanding sports achievement of this decade. Few of them are aware of the rugged road over which American hockey passed before this pinnacle was reached.

When looked at through the eyes of "Mr. College Hockey,'.' Dartmouth's veteran coach Edward Jeremiah, conditions were not always so plush for the long line of college players who contributed to this Olympic success nor for this son of destitute Armenian parents who was born in a dilapidated tenement in Worcester, Massachusetts. In his lifetime of sports participation and a near quarter century of Dartmouth coaching, he has seen them all.

It was a graduate of the Jeremiah regime of the early 1940s who led the way at Squaw Valley. Jack Riley, Dartmouth 1944, present varsity hockey coach and assistant director of athletics at West Point, guided the Olympic team to the top. He showed typical Jeremiah-bred humility by sending his Olympic picture to his esteemed teacher with this sincere autograph: "To Jerry - Hockey's Greatest Coach. Words cannot express the tremendous amount of gratitude I owe you. Without your help, Dartmouth, West Point and the Olympics would have been nothing but a dream. Thanks a million. Jack."

It has been only in the recent past that efficient ice rinks have become available on college campuses. When Jeremiah was appointed to the Dartmouth position in the fall of 1937, Davis Rink enclosed natural ice and was completely dependent on prolonged cold weather. Knowing that he was on trial on a job about which he had long dreamed, he was praying for early ice so he could get to know his players' abilities. When the local ponds teased him with a thin coating of ice through which his boys often took an unwanted swim, his hopes mounted for a continued cold snap. But the weather did not cooperate as priceless practice days went by. One day while on an outdoor ice scouting quest he paused in a rural hardware store and overheard some local fishermen discussing some excellent ice fishing. Jerry's ears pricked up and he practically yelled, "Where?" Thinking that he was a fellow fisherman, they confided, "Over to Millers Pond in Grantham."

Immediately Jeremiah sent up smoke signals for his Dartmouth "Indian braves" and they all hit the trail for twenty miles to find in the heart of the woods the most beautiful sight an iceless hockey player ever saw - a sunken, secluded, frozen pond with ice two inches thick. They had the time of their lives while the disillusioned fishermen glowered over the noise that frightened away their fish.

In this sylvan setting an outstanding coaching career began. Prosperity and long-desired security came early and fast. Plunging into a deteriorated hockey situation, Jerry proceeded to gain a championship in his first year and along with it his first confident feeling of well-being in a life of persistent economic hardship. To show it was no fluke, Jerry's boys took the Ivy title again in his second year. While Yale and Princeton managed to put this "upstart" in his place in 1940 and 1941, Jeremiah proceeded to monopolize the Ivy League by taking the next five titles in a row, winning 35 games while losing only three and tying one.

Not content with just Ivy League fare, these teams traveled nationwide, beating Michigan, Minnesota, California and splitting with Colorado and Illinois. College hockey and the name Dartmouth became synonymous. In 1947 they played Toronto to a 2-2 overtime tie to be the only American team to gain even a share in the International Intercollegiate Ice Hockey Championship. March 1948 found the Indians from Hanover, N. H., just missing the initial American college hockey title, losing to a Canadian-dominated Michigan team in the finals of the National Collegiate Athletic Association tournament. They were victimized by a whistle-blowing timekeeper — he wasn't supposed to have a whistle - that allowed Michigan to tie the score. At the time the referee disallowed the goal but it was incredibly restored by a between-period conference at which Jeremiah was not present. The disturbing change of fortune so upset the Dartmouth boys that Michigan walked off with the game in the third period. Jerry's only comment was an unprophetic, "You just can't beat those Canadians."

The closing week of the 1949 season found the Dartmouth team involved in all the hockey titles in sight. On Monday night, March 14, they defeated Harvard at Boston in an Ivy League title play-off. Tuesday night in Montreal, Canada, the University of Montreal edged them 4-3 for the international college laurels. Thursday night in Colorado Springs, Colorado, they beat those "Michigan Canadians" 4-2 to enter the final round of the N.C.A.A. championship for the second year in a row. On Saturday night, March 18, they bowed to Boston College in a heart-breaking, 4-3 decision. Thus by the margin of two one-goal losses in a four-games-in-six-days stretch covering 6000 miles by the time they returned home, Jeremiah's gallant forces barely missed the "grand slam" of college hockey. It is almost a minor item that during this five-year reign - interrupted by the war years of 1944 and 1945 - the Dartmouth teams went through 46 games without a loss.

At the close of the 1949 season Edward Jeremiah was clearly labelled "Mr. College Hockey." But the handwriting was on the wall. Warmer winters were causing real ice problems in Hanover. The great team of 1949 was forced to cancel all home games prior to mid-January and lost three of its first six games to inferior opponents. Such weather worries led to a famous Jeremiah quip, "A coach is happy when he has natural hockey players and artificial ice - unhappy when he has artificial players and natural ice."

Prospective college hockeyists are no different than any other breed of athlete. The good players do not flock to an institution whose facilities are unreliable. Even before 1949 the erosive thinning of Dartmouth material had begun. Many, many moons were to rise and set before the Hanover Indians were to come out, on top again.

As early as 1947 Coach Jeremiah had warned the Dartmouth authorities that unless ice conditions were improved bad days were ahead and indeed they were - nine long years of them. For any coach of any sport the two biggest headaches are material and facilities. The struggle was on to maintain even a .500 break-even season, reaching the depths with a 1956 result of five wins and eighteen losses. Although Jerry never lost faith in his ability, he knew himself as the Hanover "Pagliacci" - always laughing on the outside but dying on the inside.

A great tribute to his stature was the absence of the usual under-cutting, knife-in-the-back criticism by the alumni. Their feeling was a substantial belief that if Jerry couldn't do it, it couldn't be done. One hockey loving alumnus, Herbert F. Darling '26, a prominent and highly successful general contractor for dams, bridges, highways and the like, came to the rescue with a large donation toward an artificial ice plant and a willingness to lead the drive to raise the remainder of the needed funds. Darling, a graduate of Dartmouth's Thayer School of Engineering, had written a thesis to establish that New Hampshire; weather conditions could not assure consistently dependable conditions for ice hockey. His interest in the subject never waned and 26 years later he gave the impetus to the campaign that resulted in his making the presentation speech to President John Sloan Dickey when the new artificial ice plant was dedicated on December 4, 1953. With this facility the long process of rebuilding Dartmouth hockey could begin.

Many words have been written, pro and con, on the necessity of athletic recruitment. Regardless of the merits of such solicitation no coach can succeed without it. Many great and highly respected coaches have failed to maintain their status because they either could not or would not attract good players to their institutions. In an Ivy League school where scholarships are academic, the attraction must be the college and the coach and not the financial remuneration. Loyal and willing-to-work alumni are a must.

As soon as the new ice plant became an asset, the enormous influence accumulated by Jeremiah among his hockey alumni began to have its effect. His "trademark" of caring for people - players, alumni, friends, parents, prospects, and kids in general - had been solidly established with thousands of personal contacts and letters. His elaborate files are kept up to date on his many friends. Even during the war years, when as a Lt. Commander assigned to Harbor Entrance control work ending up on NDRILO island in the South Pacific, he devoted most of his spare time to writing and being a central clearing house. Letters were kept in circulation and each reader checked his name on the long list at the top of the letter to indicate that he had read it.

All through the years his home has been his players' home, during and after college, with Jeremiah as the sincere "father" to them all. One alumnus who suffered from a severe nervous disorder was steadied down by the constant receipt of letters from Jerry and from others stirred into action by their former coach. An undergraduate player whose father died suddenly, leaving him as the oldest son in a large family, was persuaded and helped to "stick it out" and finish his college education - a foundation for the important position he holds today. One fast-skating player, nicknamed "Workshop," never scored a goal but was taught to play defensively, "to cover his man and if he goes for a drink of water, you go too." This alumnus who had no all-around ability but made his contribution to a championship team will never "let Jerry down." The two mid-western fathers of moderate circumstances who had never seen their sons play for Dartmouth found themselves the recipients of an alumni-sponsored round trip to Hanover to witness a championship Dartmouth victory. They have a real feeling for Jerry and for Dartmouth. As one admiring mother whose son attended a Jeremiah summer hockey session puts it, "He is tough, and smart, interesting and fun to be with — and he has an underlying thoughtfulness and sweetness that is very endearing. He still writes my boy Bill an occasional note though he is no longer eligible for the hockey school. He is a friend."

With such a coterie of faithful friends and with sincere hard work by Jeremiah, Dartmouth's hockey fortunes were bound to pick up. The season of 1954 was the first on the new ice. The year not only marked the turning point in hockey but it also gave Coach Jeremiah the finest Christmas present he ever had. During the year he had given pretty Lois Timmons a ride home from her work at the hospital. He says, "I asked her if I could see her again and I've been seeing her ever since. Frankly, she's not a bad sight." They were married on December 24, 1954.

With the help of his devoted alumni, Coach Jeremiah concentrated on restoring Dartmouth hockey to its former top ranking. There were six "key" individuals in Dartmouth's eventual return to the top in 1959 and 1960. In the "sweating out" stage of admissions in the spring of 1955, the deserving Jeremiah was the beneficiary of an unique twist. Rod Anderson, who was to captain the 1959 championship team, was a much sought after prospect from Johnson High School in St. Paul, Minnesota. During the period of decision-making, Jeremiah recalls, "an over-talkative alumnus of a sister Ivy college put his foot in his mouth when he made some derogatory remarks about Dartmouth. Rod's innate sense of fairness made him react to the thought that if this man says such things about another man's college, then his college cannot be a good one, and that is how he decided for Dartmouth."

In turn Rod Anderson had been an idol at Johnson High, an inspiring leader. It was his influence that brought two more players to Dartmouth from his old school, "key" players Ryan Ostebo and Thomas Wahman, both of whom played on the winning teams of 1959 and 1960. Goalie Wahman was selected for the All-American hockey team in 1960 but his talents were such that he had played as a forward on the first line of the victorious team the year previous. Indicative of his other talents The Dartmouth awarded him the prized Dartmouth Cup - "to that Dartmouth athlete who by his actions on and off the field reflects glory to Dartmouth." Wahman also was the winner of a three-year Rockefeller Theological Scholarship.

Key player number four, Russell Ingersoll, captain of the 1960 title team and an All-American defense selection, came to Dartmouth through the influence of alumni in his home town of Duluth, Minnesota. Subject to some disastrous mid-season slumps in which he was his own worst enemy, he remembers a bitter day in the middle of his senior year. "In a very crucial game with Brown I lost my temper and drew an unnecessary penalty. I have never been so mad at myself and was useless for the rest of the game. Later as I got ready to leave the dressing room, Jerry blocked the door. Sullenly I told him to move and with that he blasted me. For five minutes we tore at each other in unrepeatable words, standing chest to chest. I was furious. But suddenly I realized the stupidity of the whole thing and started to laugh. That's what Jerry wanted and he let me go. I had let off the steam inside me, thanks to him, and the next day I felt like a hockey player again."

Key player five, Michael Hollern, from Wayzata, Minnesota, was a Dartmouth legacy. His father, as a sophomore, played on the 1930 Dartmouth hockey team with senior Eddie Jeremiah. Key player number six, Robert Harvey of Belmont, Massachusetts, had always planned to go to Dartmouth. In commenting on this vital group, Jerry remarked, "So you see, there wasn't too much 'recruiting' action on these men who were so instrumental in winning the 1959 and 1960 championships. But I think recruiting is here to stay. Frankly, I dislike the word because it makes me think of subsidizing. I prefer to use the word 'influencing.' "

These six invaluable players along with their teammates marked the return of Dartmouth to hockey leadership by presenting their coach with a plaque whose inscribed sentiments encompasses the feelings of Jeremiah's devoted followers. "A remembrance for Jerry who himself brought us the Ivy Championship. For instilling in the players his courage, confidence and desire to win, our continuous affections and gratitude. Dartmouth Hockey Team 1959."

Honors had continued to come Jerry's way during the nine-year hiatus in championship hockey teams. His 1951 team barely reached a .500 standing by virtue of an upset victory in the final game of the season, beating a Brown team which had already clinched the league title. Prior to this contest he had commented to the press that "it was of the nature of fulfilling contractual obligations." But his boys did him proud. In this same year the American Hockey Coaches Association made Jeremiah the first recipient of the Spencer Penrose Coach of the Year Trophy. Deeply appreciative of such a laurel in a poor year, Jerry accepted it with the remark, "I haven't been so excited since I first discovered sex."

His fellow coaches' respect for this man is comparable to that held by the townspeople of Hanover, as repressented by Maurice Aldrich, president of the Dartmouth Savings Bank. When the preliminary details were completed for Jeremiah's purchase of a house, Aldrich inquired as to how much Jerry was prepared to deposit as a down payment. Knowing that it was near the end of the month and that his bank balance was low, Jerry replied, "Mr. Aldrich, this will kill you. All I've got to my name is my $5O checkbook balance." After an eternity of silence, during which Jerry expected to be thrown out bodily, Aldrich replied, "O.K. Jerry, it's a deal." When the papers were drawn up and signed, Jerry expressed his appreciation, "Mr. Aldrich, I won't let you down." Aldrich responded, "No. I don't think you will, but I hope you realize that this house was sold to you practically on faith."

In 1952 Jeremiah was a member of the important United States Olympic Ice Hockey Selection Committee as well as being Chairman of the N.C.A.A. Eastern Hockey Selection Committee. In this latter capacity he was the first to make use of the stipulated authority to order a four-team playoff for the two selection spots. He held to this honest, courageous stand despite some violent opposition in which two of the four teams withdrew, leaving the other two to proceed to the N.C.A.A. tournament without benefit of playoffs. It was this steadfastness of character that led the coaches to elect him (Jerry says he was "blackjacked") to the office of permanent secretary-treasurer of the A.H.C.A. Many coaches have expressed the opinion that this was the greatest blessing ever granted to American hockey. Having nothing else to do in this losing period, he edited the section on Ice Hockey in the Encylopaedia Britannica and also for the Dictionary ofSports. In 1958 he completed an up-to-date second edition of the classic coaches book, Ice Hockey, published by The Ronald Press.

Indirect honors came his way when two of his former players received acclaim. Jack Riley, of 1960 Olympic fame, won the Coach of the Year Award twice, in 1957 and in 1960. Both times Jerry made the presentation. Bill Harrison, now an engineering professor at Clarkson Tech, set a terrific record as hockey coach in a four-year period from 1955 through 1958. His Clarkson teams won 74 games while losing but ten and won third-place honors in the N.C.A.A. tournaments of 1957 and 1958. But it was in 1956 that his team won 21 games, losing none, the only such record in the annals of modern college hockey. Eligibility problems prevented the team's entry into the 1956 N.C.A.A. tournament, but Harrison received the Coach of the Year Award just the same. His old coach made the presentation in front of a group of normally thick-skinned characters and there wasn't a dry eye in the room as Jerry talked with one of his boys. It was known to all that this was the boy whose father died while he was in college and who would have quit except for Jerry's help.

JERRY'S arrival at Dartmouth as a freshman, by way of Hebron Academy, all came about, he claims, because he turned left out of the auditorium on the day he graduated from Somerville, Mass., High School. Jerry had taken the commercial course and expected to look for a job. His parents, both refugees from the Turkish oppression in Armenia, worked long and hard to provide a home for their four children, of which Jerry was the oldest, and although his mother sewed, embroidered, saved, struggled and insisted that Jerry get a college education, that goal seemed beyond reach.

The left turn out of the auditorium took Jerry past Miss Campbell, head of the commercial department. She stopped him and inquired if he would be interested in a bookkeeping job with a corset concern. Jerry recalls, "In that instant my future whirled before me and I envisioned myself chained to a stool poring over corset and brassiere accounts. I gulped 'No thanks,' and ran to my high school coach, Dutch Ayer, and told him I wanted to go to college. He knew my college preparation was incomplete and he helped me to get into Hebron Academy on a scholarship." During his two years at Hebron, Jerry starred in three sports, and as captain of the hockey team he scored nine goals in one game.

One day Paul Harmon '13, a Portland business man and former Dartmouth track star, watched the Hebron baseball team at practice. Impressed by Jerry's athletic grace, he asked him if he had any college plans and if he would be interested in Dartmouth. Harmon was the first to show any interest in Jeremiah's college future, and the impact was deep and lasting. Later on other colleges sought him, but Jerry had been sold.

At college he was given a dishwashing job in Commons, and also a moderate scholarship which he proceeded to lose at the end of the first semester by flunking English. His first reaction was "This is it," but he did not quit. Through student loans totaling $2500 he stuck it out and graduated with the Class of 1930. Once again he starred in athletics, making the All-New England Football Team and the All-American Hockey Team in his senior year. A classmate says of him, "Jerry was a coach's dream - all for the team and always in perfect condition, a great competitor yet 100% clean in his constant aim to win. No one ever graduated from Dartmouth with more respect from his classmates. A poor boy, he was readily accepted by all - fellow students, faculty and townspeople."

Jerry's college vacations were spent working for the Turner Center Milk and Ice Cream Co. in Charlestown, Mass., and playing on their baseball team. All his earnings went to further his education. Upon graduation, three job opportunities were open in that depression year: teacher-coach at Franklin, Mass., High School; a business chance with the Turner Co.; and professional hockey. He chose the latter. It was a break that one of the athletic trainers at Dartmouth was Bill Stewart, later to become dean of the National League baseball umpires and coach of the Chicago Blackhawks of the National Hockey League. But in 1930 he was a scout for the New York Americans hockey club and it was on his recommendation that Jeremiah was given a contract. Jerry's choice of work was in part guided by the fact that he was secretly entertaining hopes of becoming a coach on the college level. Typical of this man with but one suit of clothes to his name and only spare change in his pocket was the fact that he countersigned his bonus check to the Dartmouth Educational Association as part payment on the loans that enabled him to complete his college education. It was the largest single payment the Association ever received.

While pro hockey was a challenge to Jeremiah, it was not a career. In the off season he helped coach school athletic teams and officiated in games. His big hockey impressions center around the famous lines he played defense against: Cook - Boucher - Cook of the New York Rangers; Jackson - Primeau - Conacher of the Toronto Maple Leafs; Seibert - Stewart - Smith of the Montreal Maroons; Weiland - Clapper - Gaynor of the Boston Bruins; Joliat - Morenz - Gagnon of the Montreal Canadiens. One night in Montreal he jokingly asked about Howie Morenz's number so that he could keep a special eye on him. After the game in which Morenz had a field day, Jerry was asked whether he had had a good look at number 7. Jerry replied, "There was no number 7 on the ice tonight but I will admit that number 7-7-7 whizzed by me all night."

He received commendable press notices in playing for New Haven, New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Cleveland, but he withdrew and was coaching hockey at Hebron in the 1934-1935 season. Before the season ended Cleveland called him back to bolster their late-season drive. Jerry remembers, "We finally made the playoffs but after eighteen games in a month and every game a crucial one, I took off my skates and called it a day."

Another big break came through his friendship with George V. Brown, president and general manager of the Boston Garden. He gave Jerry some special publicity assignments as well as the opportunity of coaching the Boston Olympics Hockey Club, a team playing in the Amateur Athletic Union. Brown assured Jerry that he was not wasting his time and that this work would eventually lead to a college coaching position. Jeremiah needed this encouragement badly for he had applied in 1934 for the hockey job at his alma mater and had been passed by without even having an interview. Now for the first time he felt that he was set on a definite course and proceeded to guide his team to the National A.A.U. championship in March 1937. Prior to this outstanding achievement job opportunities approached the "famine" category - after it came the "feast." All at the same time he was approached by Colgate and Dartmouth as well as by the Italian Government seeking an Olympic hockey coach. Facing these choices, Jerry reflects, "I probably would have accepted whichever job offer came first and I'm so happy that Dartmouth approached me first."

Jerry at last was launched on his college coaching career. He received a one-year appointment as varsity and freshman hockey coach and as assistant coach of freshman football and varsity baseball.

Before he dropped football work to concentrate on hockey when the artificial ice plant was ready for the 1953-1954 season, he had succeeded in leading the Dartmouth varsity baseball team to the Eastern Intercollegiate League championship in 1948. He still handles freshman baseball. During the football season he now operates as one of the top football officials for the Eastern College Athletic Conference.

Where does one go next - one who has won or shared in all the honors that American college hockey has to offer? One might be inclined to slow up a bit and take it easy, but not Eddie Jeremiah. This dynamic personality will never sit still. The boundless energy, enthusiasm and optimism that wear off on his players and his deep-rooted love of hockey and the individuals of all ages who play it have now produced an added summer activity.

In December 1958 Dartmouth played a series of games in Minnesota. During this visit, Lyman Wakefield '33, former national figure skating champion, showed Jeremiah the beautiful new rink he had just built in Minneapolis. It didn't take any persuasion at all to get Jerry to start a Summer Hockey School and become its first director-coach. Wakefield knew Jerry's personal powers: the ability to get along with people; his vivid imagination and wit; and his facility for explaining "why a certain thing is important rather than just the thing itself." As to Jerry, he wanted to teach summer school hockey so "I could pass on the benefits of my forty years of experience to the youngsters."

So in June 1959 Jeremiah plunged into a schedule of five two-week sessions. The groupings were for boys from 10 to 12, 13 to 15, and 16 up. Classes were to be limited to thirty boys in each group. The course was set up complete with textbook (Ice Hockey by Jeremiah), lectures, study assignments, practice drills and games, sumptuous training meals and quarters, report cards, emblems, certificates, graduation exercises and farewell banquets at the conclusion of each two-week period.

One week before the big opening there was no problem about crowding - only eleven students had signed up. Countless phone calls brought this up to 22 as the school got under way and the total attendance reached 103 by the end of the fifth session. For the 1960 school over 300 students were enrolled, and 400 are expected this year.

While he worked practically fourteen hours a day for the ten weeks, he could still be his relaxed self on the ice. All his old adages were new to the kids and they loved them. They were constantly challenged with "The puck has no brains; you must supply it." The puck must be handled with a "smart-sneaky LOOK" whereby the carrier peeks out from under his eyebrows and disguises his intentions. They were taught to be "cocky with confidence - not cocky with conceit." They must "shoot the puck at the goalie and maybe be inaccurate enough to pick a corner."

It is his quick wit and innate sense of the ridiculous coupled with fast mental reactions that puts a fresh twist on the ordinary thought. The kids love his oral change of pace. They and everybody else are entranced with the fun he gets out of life and the way in which he can be very, very close to his players without breeding the slightest amount of contempt.

Last summer John Mariucci, former star of the Chicago Blackhawks and well-known head coach of hockey at the University of Minnesota, dropped in every few days to watch Jerry at work. With all the sincerity of a father, a coach, and a friend, he says, "Knowing Eddie has been one of the nice things a coach in collegiate hockey runs into. Needless to say, Eddie has certainly been a mainstay in American hockey. I deeply admire his ability as a coach on and off the ice. My son is but seven, but if Ed hangs around long enough, I'd consider it a pleasure if my boy could play under him."

As a parent, a director of athletics, a player, or fan, think of all the good qualities you would seek to find in a coach. Lump them all together in one person and you have Edward Jeremiah. His greatest reward is to hear some parent say, "Jerry, we will never forget what you have done for our boy."

AUTHOR: Dick Vaughan was Princeton's hockey coach when Eddie Jeremiah assumed the Dartmouth post in 1937, and over the years they became good friends as well as Ivy League rivals. Vaughan retired from hockey in 1959 but continues to coach lightweight football and freshman baseball at Princeton. 1928 graduate of Yale, where he captained both hockey and baseball, he coached hockey and taught English at Andover and then was assistant coach at Yale before going to Princeton in 1935. He is former president of the American Hockey Coaches Association and was chairman of the U. S. Olympic Ice Hockey Committee in 1952.

Before artificialBefore artificial ice arrived Jerry had to find frozen ponds for practice. This was one of the surfaces thatthe surfaces that didn't give way.

Jerry, first recipient of the Spencer Penrose Coach of the Year Award, with two of his players who later won the honor: Bill Harrison '44 of Clarkson (left), winner in 1956, and Jack Riley '44 of Army, winner in 1957 and i960, who coached the winning U.S. Olympic hockey team.

Every year sons of alumni come to Hanover to play in the Whites vs. Greens hockey game that Jerry stages to their delight, and his own. He and Ab Oakes '56, freshman coach, are shown in the Davis Rink last month with the 27 Dartmouth sons who played.

Jerry in his latest roleJerry in his latest role, as Coach of the Summer Hockey School for boys held since 1959 at the new Ice Center inat the new Ice Center in Minneapolis.

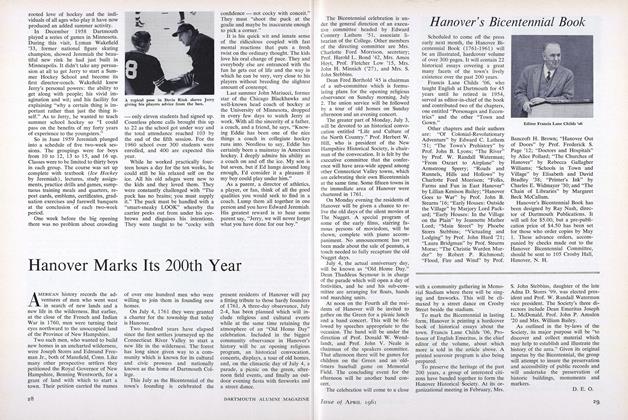

A typical pose in Davis A typical pose in Davis Rink shows Jerry giving his players advicgiving his players advice from the box.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTwo Questions About Getting Into College

April 1961 By FRANK H. BOWLES -

Feature

FeatureHanover Marks Its 200th Year

April 1961 By D.E.O. -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

April 1961 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

April 1961 By STEWART SANDERS, TOM H. ROSENWALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

April 1961 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1961 By WILLARD C. "SHEP" WOLFF, J. HENRY RICHMOND

Features

-

Feature

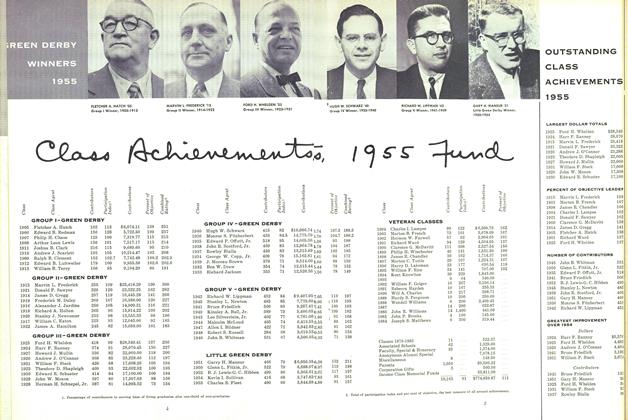

FeatureChass Achierement 1955 Fund

December 1955 -

Feature

FeatureOf Peaceful Men and Violent Ideas

DECEMBER 1968 By DEAN THADDEUS SEYMOUR -

Feature

FeatureThe Daredevil

Jan/Feb 2013 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureHope

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Jim Hardigg '44 -

Feature

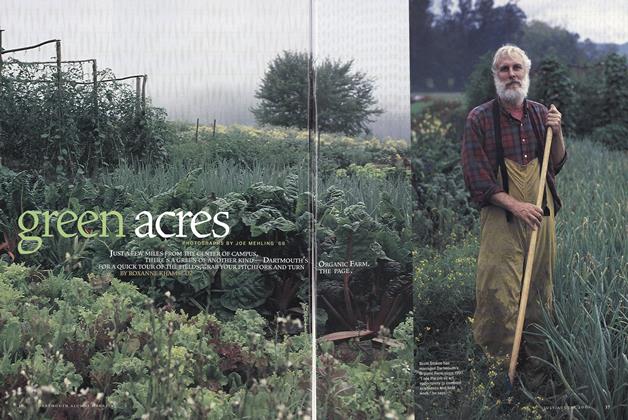

FeatureGreen Acres

July/August 2001 By ROXANNE KHAMST ’02 -

Feature

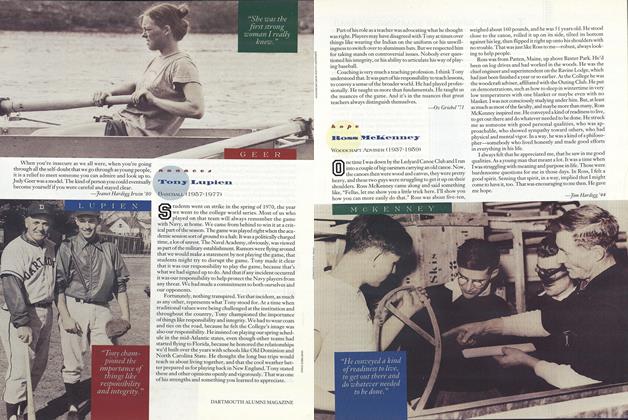

FeatureThe Quiet Good Man

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Young Dawkins '72