PRESIDENT, COLLEGE ENTRANCE EXAMINATION BOARD

WHAT ARE my child's chances of getting into college?

What can I as a parent do to improve my child's chances of getting into the college that seems best for him?

Chances are you've asked these questions, and maybe other parents have asked them of you. For admission to college has become the nation's surefire topic of conversation.

Elections, baseball and international upheavals compete for attention, of course; but these matters don't touch our personal lives. Yet it seems that every American has some contact with the business of college entrance, knows a surprising amount about it - or at least thinks he does - and wants to know more.

What he wants to know usually boils down to the two questions above.

There is a quick answer to the first question — what are my child's chances of getting into college?

Any child who has an I.Q. of ninetyfive or better, who can write a letter including a simple declarative sentence such as "I want to go to your college," who can read without moving his lips, and who can pay college expenses up to $500 a year can go to college. But it may also be true that a child with an I.Q. of 140 who can do differential equations in his head may not get to college.

Obviously, then, the general answer can only indicate that there is a tremendous range of institutions, with varying standards and opportunities, and that many factors determine actual chances of admission. For a full answer to the question, we must examine and describe these types of institutions.

As a first step, let us take a hypothetical group of one hundred high school graduates who go on to college in a given year, and see what the typical pattern of their applications and acceptances would be:

Twenty students, all from the top half of the class, will apply to sixty of the institutions that are generally listed as "preferred." Ten of them will be accepted by twenty of the institutions. Nine of the ten will graduate from their colleges, and six of the nine will continue in graduate or professional school and take advanced degrees. These ten admitted students will average six years' attendance apiece.

Seventy students, forty from the top half of the class (including those ten who did not make preferred institutions), all twenty-five from the third quarter, and five from the fourth quarter, will apply to eighty institutions generally considered "standard" or "respectable." Sixty will be accepted by one or both of the colleges to which they applied. Thirty of the sixty will graduate, and ten will continue in graduate or professional school, most of them for one - or two-year programs. These sixty admitted students will average about three years of college apiece.

Thirty students, including all of the fourth quarter and five from the third quarter, will apply to institutions that are ordinarily known as "easy." Half of these institutions will be four-year colleges, and half junior colleges or community colleges. All thirty students will be admitted. Fifteen will leave during the first year, and eight more during the next two years. The seven who receive degrees will go directly to employment, although one or two may return to college later for a master's degree in education.

AT THIS point, we need some specific . information about the types of institutions I have just mentioned.

"Preferred" institutions - the ones that receive the most attention from high school students - number from 100 to 150, depending on who makes the list. In my judgment, the larger number is correct, and the list is still growing. It should reach 200 by 1965, and 250 by 1970. The number of places available in preferred institutions — now approximately 100,000 - should increase to about 150,000 during the next decade.

The present 150 preferred colleges are located in about fifteen states - mostly in the Northeast, the northern Middle West and on the Pacific coast. Four-fifths are private, with threefourths of the total enrollment of the group. The one-fifth that are public have one-fourth of the enrollment. This proportion is changing; in a few years it will be three-fifths private and twofifths public, with a fifty-fifty enrollment split.

It now costs about $3,000 a year to send a child to a preferred institution.

"Standard" institutions - which are not selective at admission, but will not admit any student obviously destined to fail - number from 700 to 800. The larger number includes about fifty that could be considered part of the preferred list and another fifty that could be placed on the easy list. In my judgment, the smaller number is the right one for this category. It will stay about constant over the next decade, with some shifting between lists. But enrollments within the standard category will go up by at least fifty per cent.

Standard institutions are of course located in every state. Seventy per cent of their enrollments are in public institutions, and thirty per cent in private ones. But the private institutions outnumber the public ones in a ratio of sixty-forty. Many of the private colleges are remarkably small.

Costs at standard institutions tend to run from $1,500 to $2,500 per year. Yet some of these schools operate with very low fees, and naturally the public ones are in the lower cost brackets.

"Easy" institutions number about 800, of which 300 are four-year colleges and the rest junior colleges or community colleges. The list will grow rapidly as colleges are established over the next decade. Even though some easy colleges will raise, requirements and join the standard group, there may well be 1,500 colleges in this category by 1970. Enrollment will triple in the same period.

At present about one-third of the easy institutions are four-year private colleges with enrollment problems, and many of these are trying to enter the standard group. But almost all newly established institutions are tax-supported. Thus by 1970 the number of private colleges on this level of education will be negligible.

Cost of attending these institutions is now very low; tuition ranges from nothing to $500 a year.

With these descriptions established, let us consider chances of admission to these institutions, now and in the future.

The "preferred" institutions are already difficult to enter, and will become more so. In general, their requirements call for an academic standing in the upper quarter of the secondary school class, and preferably in the upper tenth. School recommendations must be favorable, and the individual must show signs of maturity and purpose. Activities and student leadership have been much overplayed, particularly by parents and school advisers, but they carry some weight as indications of maturity. Parental connections with colleges help, but are rarely decisive. If any factor is decisive, it is the school record as verified by College Board scores.

Chances of admission to any of this group of "preferred" colleges may be estimated as follows:

School record in upper ten per cent, with appropriate College Board scores and endorsement from high school - not worse than two chances out of three.

School record in upper quarter, with verifying College Board scores - not worse than one in three. This does not mean that the student will get one acceptance out of two or three tries, but rather that this estimate of chance holds for any preferred institution he applies to.

School record below the upper quarter, with strong counterbalancing factors, such as high College Board scores, remarkable personal qualities, proven talents in special fields, strong family connections, recent awakening of interest and excellent performance, achievement despite great handicaps - not better than one chance in three, and not worse than one chance in four.

No others need apply.

The "standard" institutions are, taken as a group, still accessible to any student whose past performance or present promise gives reasonable chances of college success. But there are gradations within the standard institutions. Some approach the selectiveness of the preferred group; others are purposefully lenient in their admissions and stiffer in later "weeding out" during the first year of college.

A student shows reasonable chance of success when he has taken a secondary school program including at least two years of mathematics, two years of a foreign language, and four years of English, has passed all subjects on the first try, and has produced good grades in at least half of them. This means a school record not too far below the middle of the class, at worst. Now that nearly all standard institutions are requiring College Boards or similar types of examinations, the school record has to be backed by test scores placing the student in the middie range of applicants (CEEB scores of 400 or higher).

Such a student can be admitted to a standard institution, but he may have to shop for vacancies, particularly if his marks and scores are on the low side and if he comes from a part of the country where there are more candidates than vacancies. Thus students in the Northeast often have to go outside their region to get into a standard college, even if they have excellent records. On the other hand, where there is still room for expansion, as in the South and parts of the Middle West, students may enter some of the standard institutions with records that are relatively weak.

Students with poor records or poor programs who still offer unusual qualifications, such as interest in meteorology or astronomy, students who wish to follow unusual programs in college, or students who are otherwise out of pattern will often find it difficult to enter standard institutions. Curiously enough, they may well encounter greater difficulty with such institutions than they would have with many in the preferred category. In other words, standard institutions are "standard" in many senses of the word.

"Easy" institutions are by definition non-selective. We can make several generalizations about them:

First, any high school graduate can enter an easy institution, regardless of his I.Q., or his studies in school, or what he hopes to do in college and after.

Second, an easy college usually offers a wide range of courses, all the way from a continuation of the general high school course, to technical and semi-professional programs, to the standard college subjects.

Third, easy colleges will draw some well-prepared students who later go on to advanced degrees.

Fourth, since easy colleges are not selective (neither keeping students out nor forcing them out), they must operate so that students will make their own decisions, and thus they must have a strong institutional emphasis on guidance.

Fifth, since one of the most powerful of all selective devices is the charge for tuition, easy colleges tend to charge low, or no, tuition.

Sixth, easy colleges are a consequence, not a cause, of enlarged demand for higher education. Even when they offer programs which a few years ago would not have been considered as college work, they do so in response to demand. And the demand is increasing. Total enrollment in higher education in 1970 will be about double that of today, and it may well be that this type of institution will account for from one-third to one-half of that total. The number and size of these institutions will increase, and they will become widely distributed throughout the country, instead of being concentrated on the Pacific coast and in the Middle West as they are now. Thus in 1970 it will still be possible for any student to enter college.

To sum up, then, the answer to our first question is that a student's chances of getting into college are excellent - provided that he is able and willing to do what is necessary to prepare himself for the college he would like to enter, or that he is willing to enter the college that is willing to accept him.

LET'S TURN now to our second question: What can I as a parent do to improve my child's chances of getting into the college that seems best for him?

This is one of the standard, rather heavy questions for which there are already available a great many standard, rather heavy answers, dealing with the desirability of the good life, the need for stable parents and other valid but unenlightening pronouncements. But some of the problems raised by this question do not yield to standard answers. Three such problems, or needs, deserve our attention:

1. The need for parents to promotethinking, learning and reading.

Colleges, particularly the preferred colleges, are bookish places. They emphasize reading and discussion as stimuli to learning and thinking instead of stressing note-taking and the study of textbooks to accumulate facts. College entrance tests are built in part to measure reading skills. And the student with the habit of reading will do better work in college than the student who relies on studying textbooks and memorizing facts.

The habit of reading is most easily formed at home. It can be formed by the presence and discussion of books. This means, for example, that the fifty dollars that parents often spend on coaching for college entrance tests can better be spent over two years in the collection of fifty or sixty "highbrow" paperbacks. For this is reading that will do more than any coaching courses to improve test scores - and it will at the same time improve preparation for college studies, which coaching courses do not do.

2. The need for parents to makefinancial preparation for college.

College is a costly business. The preferred colleges cost about $3,000 a year, and of course this comes out of net income after taxes have been paid. For most families with children in college, it represents gross income of at least $4,000. Referring back to the average span of six years' attendance for students who enter a preferred college, the family of such a student must dedicate $24,000 of gross income for his college expenses.

Not long ago, a survey showed that half of a group of parents who expected their children to go to college did not know the costs of college and were not making any preparations to meet those costs. The lesson is obvious. Parents who are not ready to deal with college costs are failing in a vital area of support. Urging a child to study so that he can get a scholarship may pay off, but it is a poor substitute for a family plan for financing of the child's education.

3. The need to choose a college interms of the child's abilities and interests.

Much is made of the problem of choosing colleges, and great effort goes into the process of choice. But the results, if judged by the turmoil that attends the annual selections, fall far short of expectations. The difficulty seems to lie in the placing of emphasis on the college, not the student. When the application is sent in, the parent often knows more about the merits of the college to which the application is going than he does about the applicant as an applicant.

Naturally it is difficult for a parent to be objective about his own child. But enough is now known about evaluating individual abilities and achievements that any parent who really wants to may view his child as the child will be viewed by the college. Such an evaluation is neither so difficult nor so time-consuming as the processes parents often go through in evaluating colleges. And since it relies on standard academic information, it involves little or no cost. Yet its value is inestimable. For if the choice of college is made in terms of the child's capabilities, the first and most important step has been taken toward placing the child in the college that seems best for him. And this in turn is the best insurance for a successful college career.

FRANK BOWLES, who has been director, andnow president, of CEEB since 1948, is oneof the country's top authorities on "How toGet Into College," the title of a book hewrote in 1958 and revised last year. Graduate of Columbia in 1928 (M.A. '30), he wasdirector of university admissions at Columbia before going to the College Board.

Copyright 1961 by Editorial Projects for Education, Inc. All rights reserved.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJERRY

April 1961 By RICHARD F. VAUGHAN -

Feature

FeatureHanover Marks Its 200th Year

April 1961 By D.E.O. -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

April 1961 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1956

April 1961 By STEWART SANDERS, TOM H. ROSENWALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

April 1961 By NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOSHUA B. CLARK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

April 1961 By WILLARD C. "SHEP" WOLFF, J. HENRY RICHMOND

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1962 -

Feature

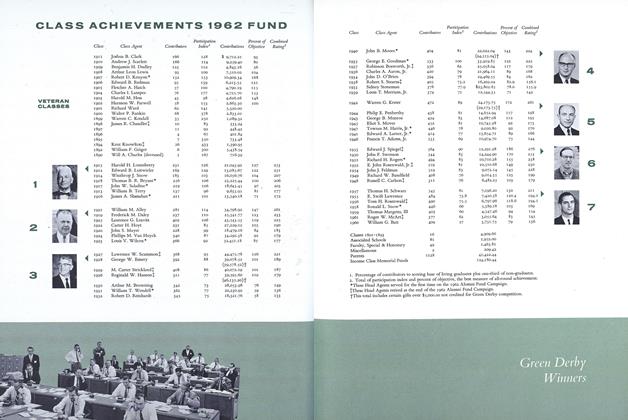

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVEMENTS 1962 FUND

NOVEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureA New Look for Reunions

JULY 1966 -

Cover Story

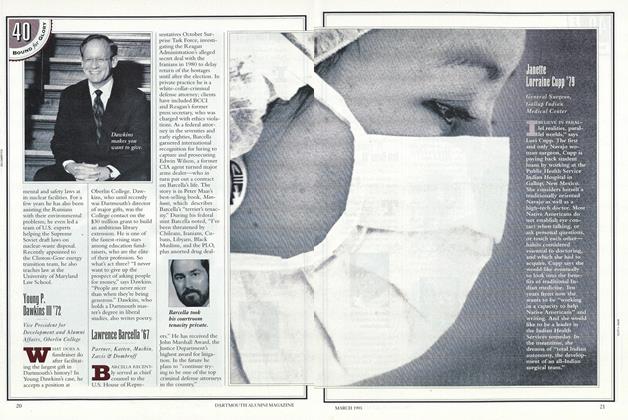

Cover StoryLawrence Barcella '67

March 1993 -

Feature

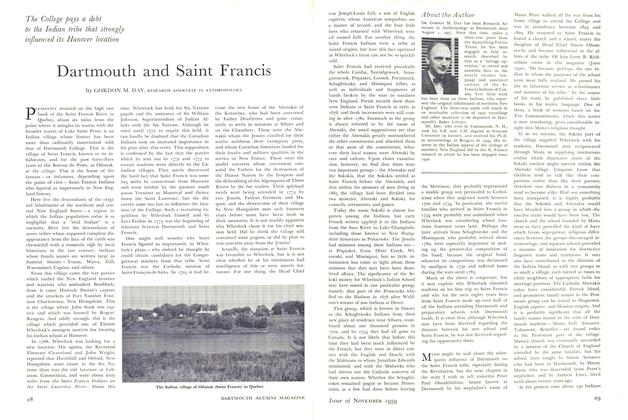

FeatureDartmouth and Saint Francis

November 1959 By GORDON M. DAY -

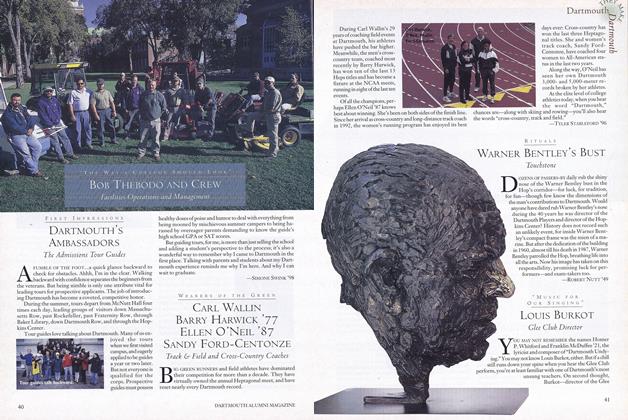

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth's Ambassadors

OCTOBER 1997 By Simone Swink '98