ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF GOVERNMENT

THE central issue in American education today - and, indeed, in the very survival of our free way of life - involves what a recent commentator in The Atlantic magazine called, "the great want of genuinely good teachers."

During recent years, the teacher has come of age in our national consciousness, due to the basically simple, albeit terrifying, fact that we are in deep trouble on this vitally important front. We are in trouble at home, where a burgeoning new generation is straining our existing educational resources to the breaking point, and we are in trouble abroad, where a fanatically vigorous opposition is demonstrating striking capabilities of an economic, political and technological nature which we had previously thought to fall within our own exclusive area of competence. These may well be the wrong reasons to stimulate a long overdue recognition of the value of good teaching, yet it can hardly be denied that their practical impact on our teachers is a very direct one. Be she the kindly, graying matron on the kindergarten playground, or be he the fair-haired young Ph.D. in the physics laboratory, the American teacher is now in demand as never before in our history. Thus, it is both appropriate and gratifying to lave this opportunity to talk with you about the challenge of teaching as a career, and more specifically within the framework of this conference, to discuss the potentialities of teaching as a Christian vocation.

At the outset, let me express two limitations regarding my remarks. First, my experience as a teacher is not very lengthy. As a matter of fact, I have just recently completed my first year as a faculty member, and hence, my observations and impressions may be somewhat misleading. However, since I have also had an opportunity to gain some experience in the fields of government service and educational administration, I hope I can at least bring the perspective of comparison, if not of lengthy exposure, to my remarks. Second, the parallels between teaching and religion seem to me to be so numerous that it is difficult to know where to begin. A few years ago, if I were concentrating on strictly practical criteria, I would have been tempted to note that a teacher can fulfill his Christian obligations, quite neatly, by swearing to a lifelong vow of poverty, and let the discussion go at that. Fortunately, however, I am now reasonably confident that if you decide to select teaching as a career, you will find it to be an adequate, if not gluttonous, way in which to earn your bread and keep. Yet it is not my intention here to concentrate upon salary scales, fringe benefits and the like, but rather to try to sharpen a few of the parallels, noted above, in an effort to provide some guidelines which will hopefully be of use to you in considering whether teaching would have any real appeal as a lifetime commitment.

To begin with the most obvious parallel of all, we can note that teaching played a central role in the lives of our greatest religious figures of all faiths. Confucius, Moses, Gautama Buddha, Mohammed - the list is endless, for each of these inspirational leaders was dedicated to the teaching of a way of life to his fellow men. When we turn to the Christian faith, we can find in the New Testament a summation of the great teaching heritage which Christ left to all mankind.

The most basic, and the most significant, parallel, then, is to be found in the fact that teaching was central to Jesus' ministry, and this is a fact that has very real meaning in terms of what we are trying to understand here today. For if we can probe a bit into the essence of such a monumental teacher, we will gain a clearer insight into the rewards and frustrations of teaching as they relate to our own aspirations in life. It is both heartening and humbling to gaze upon an ideal, even when this ideal is far removed from our own personal aptitudes and capabilities.

In viewing Jesus as a teacher, I feel two questions stand out as being of special relevance to us today. First, whom did he teach? And second, how did he teach? By clarifying these questions in your own mind, you will have gone a long way in understanding whether or not teaching has any basic meaning for you.

The answer to the first question is, of course, obvious. He taught anyone and everyone without discrimination; his message is universally directed to all men, regardless of intellectual qualifications or personal station in life. Indeed, here was one of the most difficult and baffling facts his opponents had to face, and they responded with cries of derision and contempt. Yet the fact remains that Jesus directed his message to both the high and the lowly, to both the gifted and the unspectacular, ranging from the Sadducees and the Publicans to a variety of misfits and unfortunates - the lunatic child; the ten lepers; the deaf, the dumb and the blind; the woman taken in adultery - who appear and reappear throughout the New Testament.

The of this fact to the present-day teacher is direct and significant, for it dramatizes the responsibility which all teachers have had to face throughout the ages - the responsibility to deal with a variety of student interests, outlooks, capabilities and, above all, motivations which range from the very cool to the blazing hot, and which, more often than not, bear only the faintest resemblance to what you expect to meet in the classroom.

I recently heard John Finley, Harvard's distinguished Eliot Professor of Greek Literature, speak to this point at a Harvard Business School forum, and the analogy he drew was interesting and rewarding enough to bear repeating here. Professor Finley pointed out that the great majority of college students have always fallen into two basic categories. On the one hand, there is a small cluster of "poets" - those intellectually-oriented students who seem to revel in their academic pursuits, and who go on, with little or no prodding, to become great scholars, researchers and intellectual leaders in their own right. On the other hand, there is a much larger, and more difficult, group of "squires" - those pragmatically-minded students who will later make their marks as men of affairs, but who, in the interim, do not always find the type of stimulus in the classroom which they need if they are to excel to the full extent of their capabilities. After pointing to the relative ease and pleasure with which the teacher can stimulate the "poets," and the corresponding difficulty which he often faces with the "squires," Professor Finley asked if we, as teachers, were doing as much as we should be doing for this latter group.

I am afraid the temptation is obvious, and I feel the challenge is a major one. It is always easy to deal with the highly motivated student. The real test comes in how well you can do with those whom our Deans euphemistically refer to as the "under-achievers." And let's face it quite honestly, regardless of the most heroic efforts of our admissions officers, all educational institutions are going to have their fair share of difficult cases. There is at least a parcel of truth in that cryptic remark of Mr. Dooley to Mr. Hennessy that certainly he would send his boy to the university because "at th' age whin a boy is fit to be in colledge, I wudden't have him around th' house."

Hence, if you feel you want to go into teaching, I urge you to look at both sides of this partcular coin, for you too will find yourself dealing with the high and the lowly, with the gifted and the unspectacular. And this involves its frustrations as well as its rewards, because no matter how hard you may try there will be times when you cannot help realizing, deep inside, that you simply did not get through to your class, or to individuals within that class. Despite the apparent quietude of the academic environment and such tempting enticements as sabbatical leave, all is not sweetness and light in the teaching profession. As a practical matter, a great deal of teaching can, and does, involve personal disappointment and personal defeat, and if you are not prepared to face this fact, teaching is not for you.

If the first test that Jesus, the teacher, poses for us is difficut, the second is even more demanding. If we were to make only a surface inquiry into how Jesus taught, we could cite the parables and the other devices which he employed to make his message meaningful to mankind. Yet when we bother to dig just a little deeper, we must conclude that Jesus actually went much further than this. In essence, he taught, first and foremost, through the example of what he was, through the very life he lived, and here again we have a fact which is of very direct relevance to our inquiry today.

Earlier in this talk, I mentioned the hazards of comparing ourselves to the ideal, and I do not now intend to suggest that, in order to be a good teacher, you must be a saint, lifted above the realities of everyday life. Yet, on the other hand, the kind of person you aspire to be is not totally unrelated to your effectiveness as a teacher. As Dartmouth's late, great Provost, Donald Morrison, noted in an article on the requirements of a good college teacher, "what a teacher is, as a human being, is as important as what he knows or can learn."

The truth of the matter is that one of the most difficult temptations the teacher faces is to be found inside, rather than outside, the classroom. Ideally, a teacher can be viewed as a custodian of the accumulated knowl- edge of the human race as it relates to that particular area of inquiry which is his special concern, and as such he bears a responsibility to himself, to his students and to his fellow men to hold this knowledge in trust. Yet knowledge today is accumulating and fragmenting so rapidly that it is a frightfully demanding job just to stay up with the pack, much less blaze brave new trails of one's own. Under the pressure of everyday demands, the temptation to slack off, to cut corners, to give misleading, if not inaccurate, answers rather than admit a lack of knowledge to your students is a very real one. There lurks in every teacher the danger of attempting to teach what he knows not, and in the process, as Professor Charles Beye of Stanford University, the author of the previously mentioned Atlantic article, points out, to become "the master of the glib, the half truth, the metaphysical generalization clothed in ornate language so ambiguous as to defy analysis."

The temptation is there, yet if the teacher does nothing else, he must always be on guard against compromising the truth as he sees it. In this way he can stand as an example to his students, and in this way, he can have his most profound effect upon their future growth.

In addition to teaching by example, Jesus posed one final test for today's teacher which I find to be by far the most significant and demanding of all, for if we look directly into the very essence of Jesus as a teacher, we will find that he made his deepest impact through the process of giving himself to mankind. One of the crucially central lessons of Christianity is that Jesus (rave himself to his fellow men in order that they might find themselves, and in a very similar manner, the good teacher must give himself to his students in order to make a basically meaningful impact upon their lives. As Alfred North Whitehead explained, the teacher's function is to stimulate and guide the creative impulse toward growth which is within the individual, and in the end analysis, you can only stimulate, you can only really challenge, a student by giving a part of your enthusiasm for your subject of inquiry to him. In Emerson's tersely accurate phraseology, "he teaches who gives."

Perhaps the significance of this fact can be seen most clearly if we turn to the symbolism of light - a concept which has been associated with both education and religion from the very beginning. On the one hand, we speak of the light of learning, the spark of knowledge. On the other hand, this very same symbolism is used in describing the life of Jesus - "the light of the world," "the burning and shining light," "the light of life." The analogy is an apt one, and I hope its meaning is clear to you. Be it the candle on the altar or the teacher in the classroom - light can only be produced through the process of self-consumption. A deep and enthusiastic sense of personal commitment to his students and to his subject of inquiry is the ultimate obligation which any teacher has to make, if he is to call himself a teacher at all. And by making such a commitment, he will find teaching to be the most enriching and rewarding experience possible.

Thus, the parallels which I find to exist between teaching and the Christian life are significant for me. A basic sense of responsibility to your students and fellow men, to yourself, to your subject of inquiry and to your faith; a concurrent sense of responsibility to truth as you see it; and a deep sense of personal self-commitment are the central ingredients of each. Yet, in the final analysis, a teaching career is certainly not the exclusive monopoly of any given faith. In the end, the important point is that any truly effective teacher will find his own meaningful way to relate himself to God as he understands him. In the words of Provost Morrison, "a good teacher is almost certain to have . . . some firm convictions about what is worth living and dying for. He may, or may not, profess religious faith, but he knows enough to have at least a reverent view of the universe."

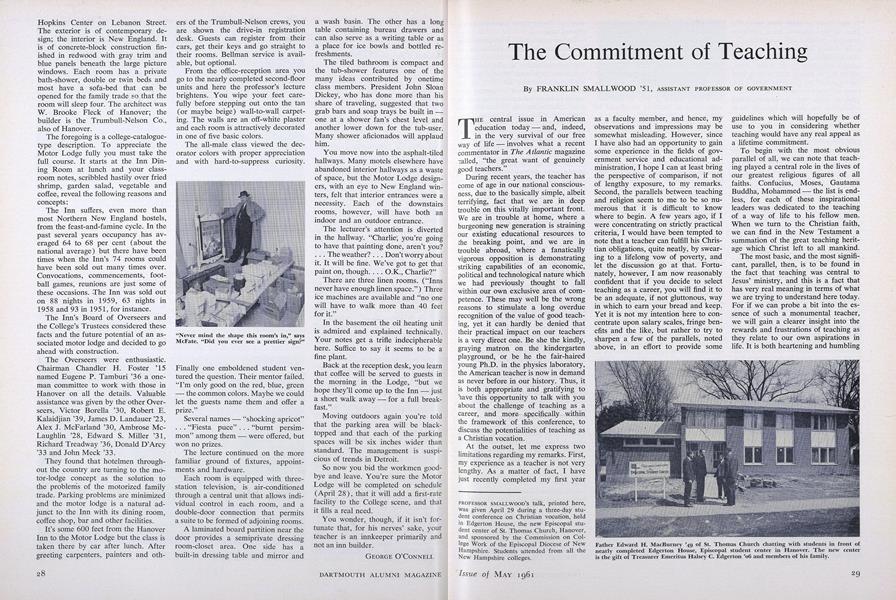

Father Edward H. MacBurney '49 of St. Thomas Church chatting with students in front ofnearly completed Edgerton House, Episcopal student center in Hanover. The new centeris the gift of Treasurer Emeritus Halsey C. Edgerton '06 and members of his family.

PROFESSOR SMALLWOOD'S talk, printed here, was given April 29 during a three-day student conference on Christian vocation, held in Edgerton House, the new Episcopal student center of St. Thomas Church, Hanover, and sponsored by the Commission on College Work of the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire. Students attended from all the New Hampshire colleges.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureArms Control in a Cold War

May 1961 By GENE M. LYONS, -

Feature

FeatureThe Human Revolution and World Peace

May 1961 By RICHARD W. STERLING, -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Defense on the Economy

May 1961 By GEORGE E. LENT, PROFESSOR -

Feature

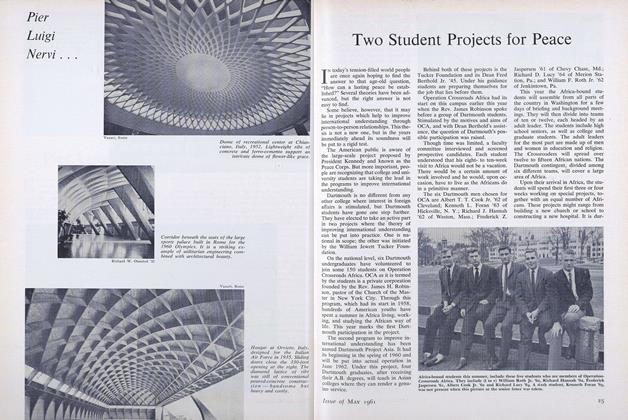

FeatureTwo Student Projects for Peace

May 1961 By D.E.O. -

Feature

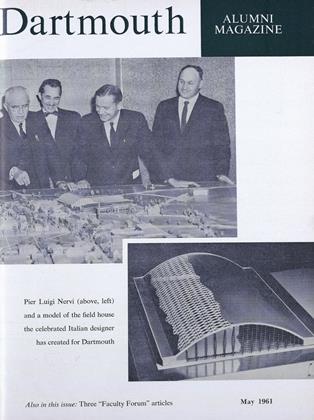

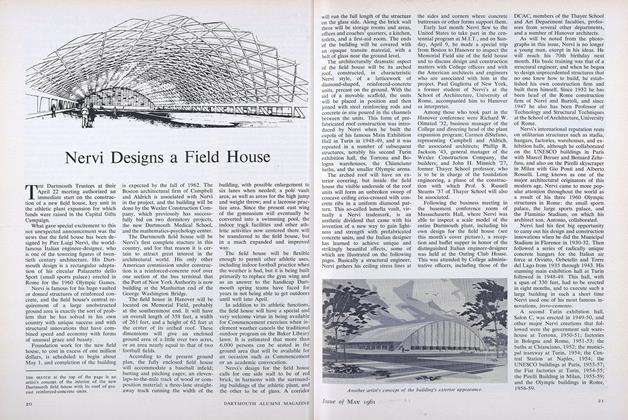

FeatureNervi Designs a Field House

May 1961 -

Feature

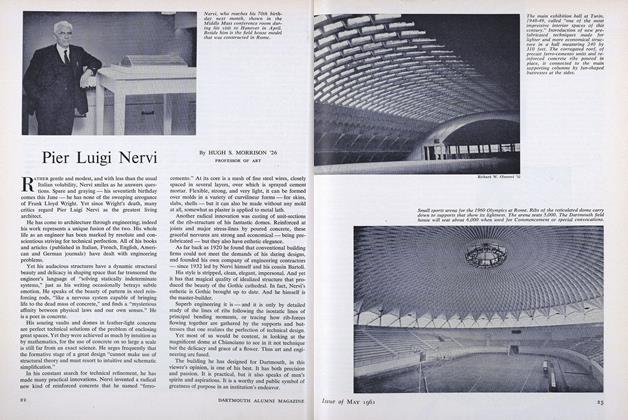

FeaturePier Luigi Nervi

May 1961 By HUGH S. MORRISON '26

Features

-

Feature

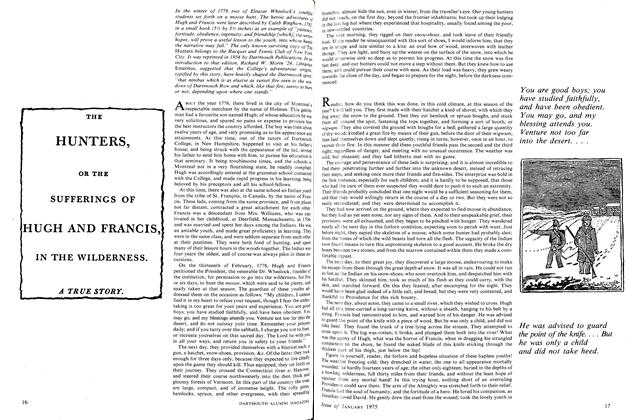

FeatureTHE HUNTERS, OR THE SUFFERINGS OF HUGH AND FRANCIS, IN THE WILDERNESS.

January 1975 -

Cover Story

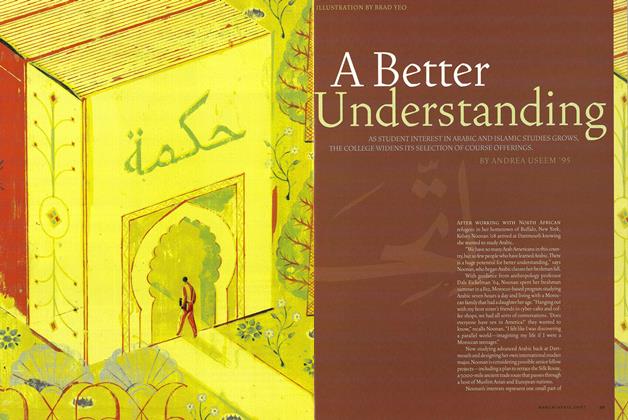

Cover StoryA Better Understanding

Mar/Apr 2007 By ANDREA USEEM ’95 -

FEATURES

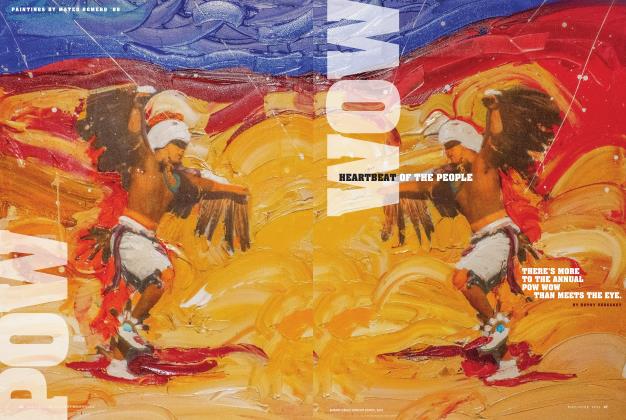

FEATURESHeartbeat of the People

MAY | JUNE 2021 By BETSY VERECKEY -

Feature

FeatureA China Perspective

OCTOBER • 1986 By President David T. McLaughlin '54 -

Feature

FeatureHow the Dutch Handle It

JUNE 1973 By Robert D. Haslach '68 -

Feature

FeatureTesting the Body's Competitiveness

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Teri Allbright