PROFESSOR OF ART

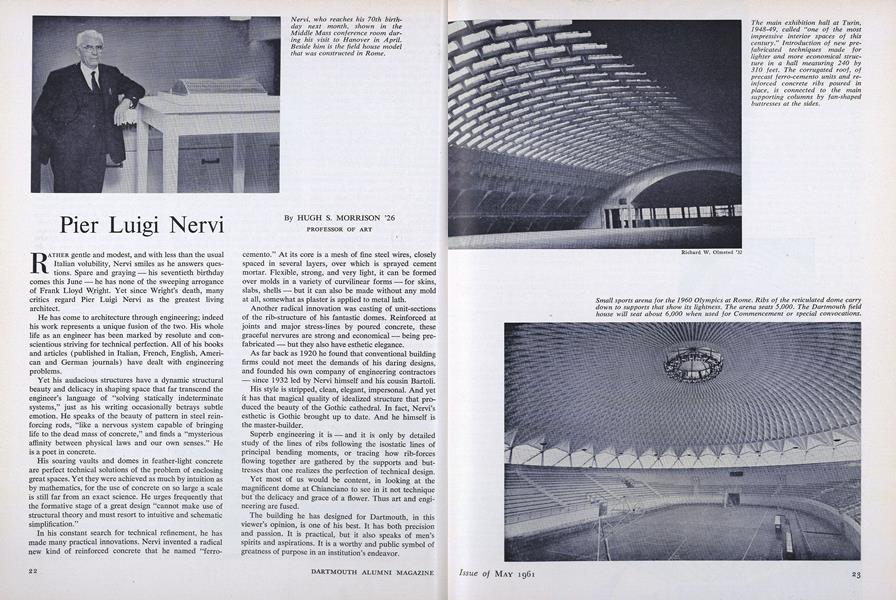

RATHER gentle and modest, and with less than the usual Italian volubility, Nervi smiles as he answers questions. Spare and graying - his seventieth birthday comes this June - he has none of the sweeping arrogance of Frank Lloyd Wright. Yet since Wright's death, many critics regard Pier Luigi Nervi as the greatest living architect.

He has come to architecture through engineering; indeed his work represents a unique fusion of the two. His whole life as an engineer has been marked by resolute and conscientious striving for technical perfection. All of his books and articles (published in Italian, French, English, American and German journals) have dealt with engineering problems.

Yet his audacious structures have a dynamic structural beauty and delicacy in shaping space that far transcend the engineer's language of "solving statically indeterminate systems," just as his writing occasionally betrays subtle emotion. He speaks of the beauty of pattern in steel reinforcing rods, "like a nervous system capable of bringing life to the dead mass of concrete," and finds a "mysterious affinity between physical laws and our own senses." He is a poet in concrete.

His soaring vaults and domes in feather-light concrete are perfect technical solutions of the problem of enclosing great spaces. Yet they were achieved as much by intuition as by mathematics, for the use of concrete on so large a scale is still far from an exact science. He urges frequently that the formative stage of a great design "cannot make use of structural theory and must resort to intuitive and schematic simplification."

In his constant search for technical refinement, he has made many practical innovations. Nervi invented a radical new kind of reinforced concrete that he named "ferrocemento." At its core is a mesh of fine steel wires, closely spaced in several layers, over which is sprayed cement mortar. Flexible, strong, and very light, it can be formed over molds in a variety of curvilinear forms - for skins, slabs, shells - but it can also be made without any mold at all, somewhat as plaster is applied to metal lath.

Another radical innovation was casting of unit-sections of the rib-structure of his fantastic domes. Reinforced at joints and major stress-lines by poured concrete, these graceful nervures are strong and economical - being prefabricated - but they also have esthetic elegance.

As far back as 1920 he found that conventional building firms could not meet the demands of his daring designs, and founded his own company of engineering contractors - since 1932 led by Nervi himself and his cousin Bartoli.

His style is stripped, clean, elegant, impersonal. And yet it has that magical quality of idealized structure that produced the beauty of the Gothic cathedral. In fact, Nervi's esthetic is Gothic brought up to date. And he himself is the master-builder.

Superb engineering it is - and it is only by detailed study of the lines of ribs following the isostatic lines of principal bending moments, or tracing how rib-forces flowing together are gathered by the supports and buttresses that one realizes the perfection of technical design.

Yet most of us would be content, in looking at the magnificent dome at Chianciano to see in it not technique but the delicacy and grace of a flower. Thus art and engineering are fused.

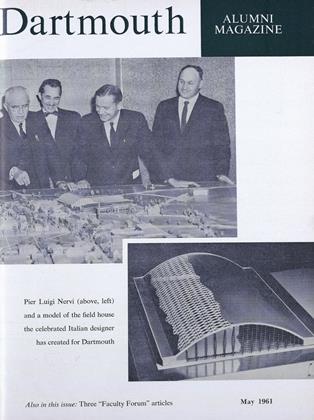

The building he has designed for Dartmouth, in this viewer's opinion, is one of his best. It has both precision and passion. It is practical, but it also speaks of men's spirits and aspirations. It is a worthy and public symbol of greatness of purpose in an institution's endeavor.

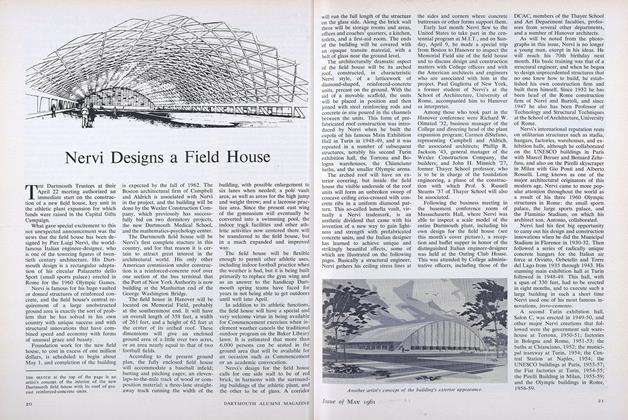

Nervi, who reaches his 70th birthday next month, shown in theMiddle Mass conference room during his visit to Hanover in April.Beside him is the field house modelthat was constructed in Rome.

The main exhibition hall at Turin,1948-49, called "one of the mostimpressive interior spaces of thiscentury." Introduction of new prefabricated techniques made forlighter and more economical structure in a hall measuring 240 by310 feet. The corrugated roof, ofprecast ferro-cemento units and reinforced concrete ribs poured inplace, is connected to the mainsupporting columns by fan-shapedbuttresses at the sides.

Small sports arena for the 1960 Olympics at Rome. Ribs of the reticulated dome carrydown to supports that show.its lightness. The arena seats 5,000. The Dartmouth fieldhouse will seat about 6,000 when used for Commencement or special convocations.

Dome of recreational center at Chianciano, Italy, 1952. Lightweight ribs ofconcrete and ferro-cemento support anintricate dome of flower-like grace.

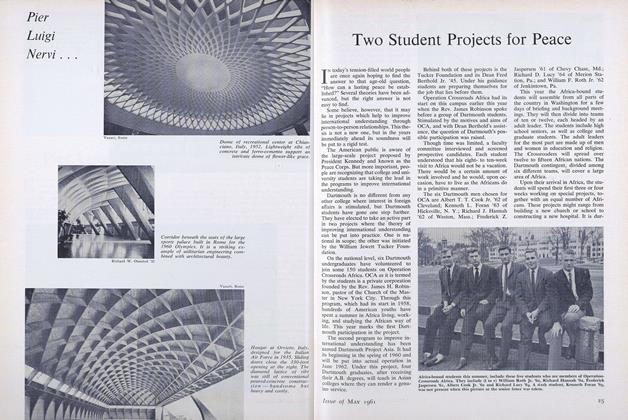

Corridor beneath the seats of the largesports palace built in Rome for the1960 Olympics. It is a striking example of utilitarian engineering combined with architectural beauty.

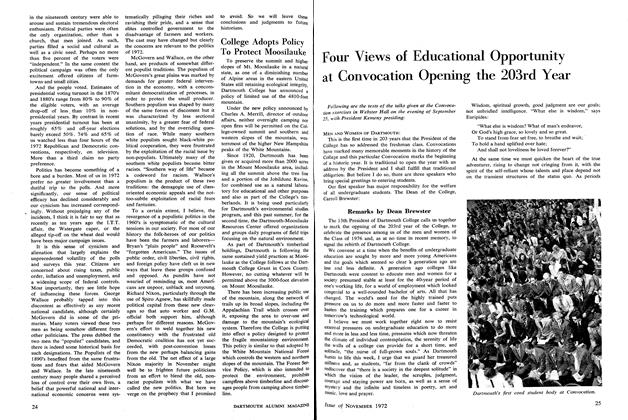

Hangar at Orvieto, Italy,designed for the ItalianAir Force in 1935. Slidingdoors close the 330-footopening at the right. Thediamond lattice of ribswas still of conventionalpoured-concrete construction - handsome butheavy and costly.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

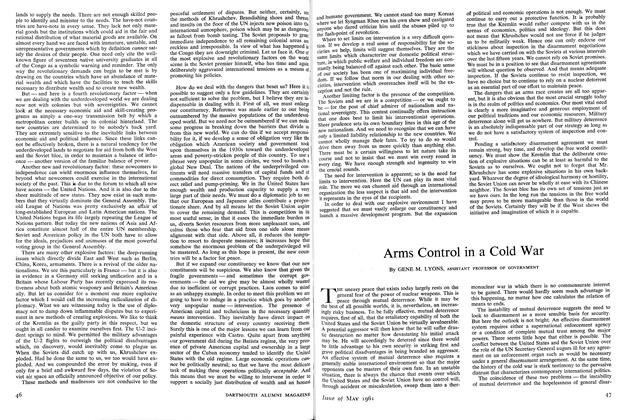

FeatureArms Control in a Cold War

May 1961 By GENE M. LYONS, -

Feature

FeatureThe Human Revolution and World Peace

May 1961 By RICHARD W. STERLING, -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Defense on the Economy

May 1961 By GEORGE E. LENT, PROFESSOR -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Teaching

May 1961 By FRANKLIN SMALLWOOD '51, -

Feature

FeatureTwo Student Projects for Peace

May 1961 By D.E.O. -

Feature

FeatureNervi Designs a Field House

May 1961

Features

-

Feature

FeatureFour Views of Educational Opportunity at Convocation Opening the 203rd Year

NOVEMBER 1972 -

FEATURE

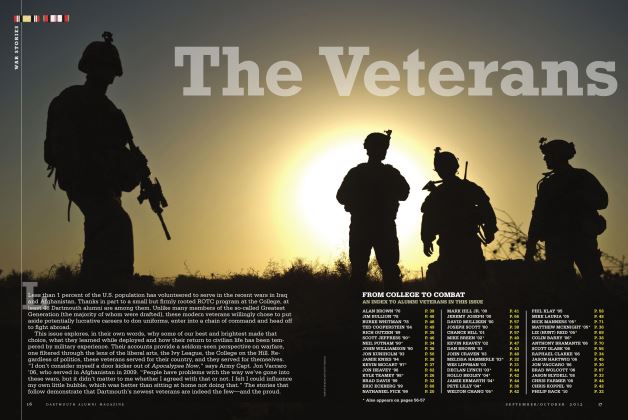

FEATUREThe Veterans

Sep - Oct By COMPILED BY LISA FURLONG -

Cover Story

Cover StoryPiece of the Action: The Testa Hit

OCTOBER 1994 By George Anastasia -

Feature

FeatureSafe Haven

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2019 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

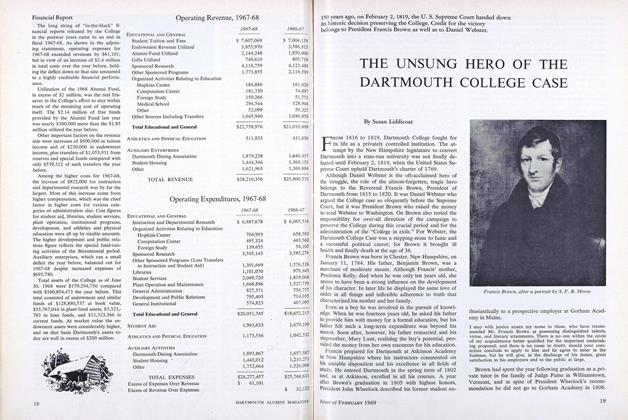

FeatureTHE UNSUNG HERO OF THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CASE

FEBRUARY 1969 By Susan Liddicoat -

Cover Story

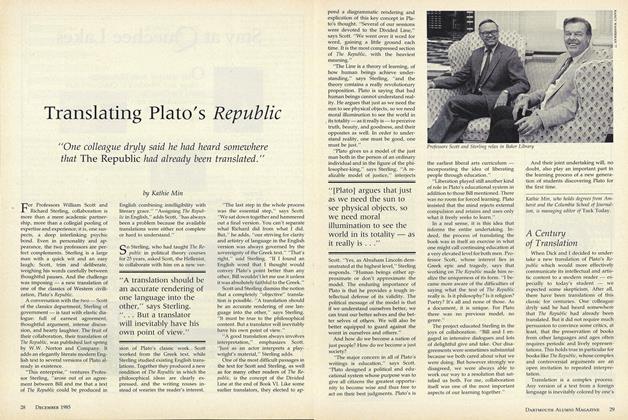

Cover StoryA Century of Translation

DECEMBER • 1985 By WILLIAM C. SCOTT