By David Roberts.New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960.369 pp. $6.00.

This very valuable piece of historical research is an outgrowth of Professor Roberts' doctoral dissertation submitted to Yale University in 1952. Much more material has been used and the scope of the work has been greatly broadened in the published volume under review.

Professor Roberts has studied in very great detail the various social reforms which were enacted in England between 1833 and 1854. In many fields - hours and conditions in factories and mines, poor relief, prison administration, education, and public health - measures were passed setting higher standards and establishing boards or commissions to enforce them. One of the most fascinating parts of the book is the very careful study which Professor Roberts has made of the social and educational backgrounds. and the political and social outlooks of the men who were appointed to the government commissions which administered the measures, or who went into the field as inspectors to see that they were carried out. Administrative history is usually very dull, but Professor Roberts has made it come alive through the detail he has managed to unearth about the administrators themselves.

The drive for these reforms came chiefly from two sources, the Evangelical humanitarianism of men like Lord Shaftesbury and the passion for good government of the Utilitarian disciples of Jeremy Bentham like Edwin Chadwick. Perhaps, the most important and interesting theme of the entire book is the paradoxical one that the Utilitarians, who basically accepted the economic laws of laissez-faire and who opposed any extension of government activity, nevertheless contributed in the long run to the foundations of what may be called "the welfare state." By their principle of "the greatest good of the greatest number" they were almost forced to advocate the removal of such obviously evil conditions as child labor, cruel practices in the prisons, and the horrors of slums. Repeatedly Professor Roberts makes the point that the powers of the central government increased not because the reformers were wedded to broad principles of reform, but because the Industrial Revolution had created social evils which cried aloud for solution and because at the same time the scientific and technical advances of this period had furnished the means by which many of the evils could be remedied.

Only by a careful reading of the book can Professor Roberts' sophisticated and judicious analysis of these complex developments be appreciated. Equally impressive is the bibliography which shows that he has drawn material from an almost unbelievable number of sources - general histories and monographs, contemporary newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets, biographical and autobiographical accounts, printed government papers, and manuscript collections in government archives, libraries, and private homes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureArms Control in a Cold War

May 1961 By GENE M. LYONS, -

Feature

FeatureThe Human Revolution and World Peace

May 1961 By RICHARD W. STERLING, -

Feature

FeatureThe Impact of Defense on the Economy

May 1961 By GEORGE E. LENT, PROFESSOR -

Feature

FeatureThe Commitment of Teaching

May 1961 By FRANKLIN SMALLWOOD '51, -

Feature

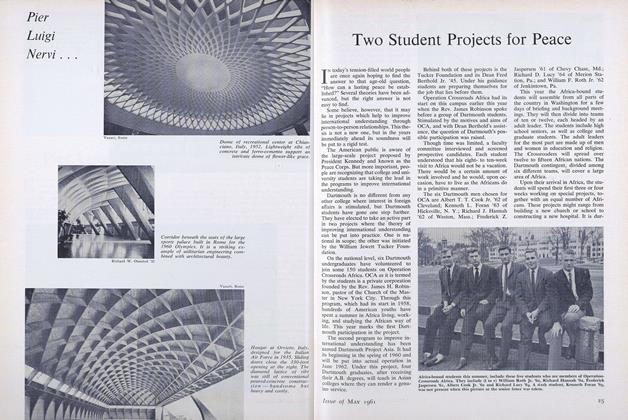

FeatureTwo Student Projects for Peace

May 1961 By D.E.O. -

Feature

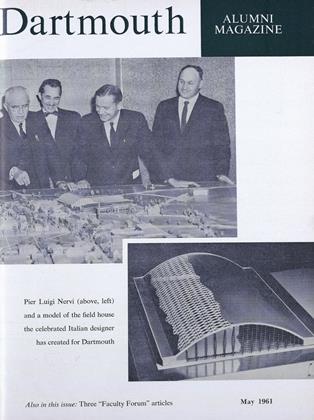

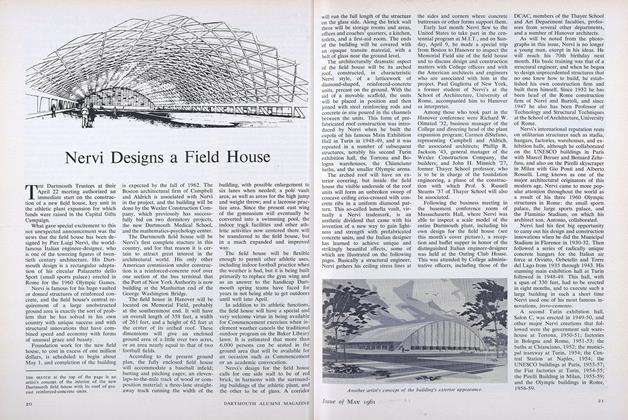

FeatureNervi Designs a Field House

May 1961

JOHN G. GAZLEY

-

Books

BooksTHE DRAMA OF UPPER SILESIA

June 1936 By John G. Gazley -

Books

BooksFRENCH FOREIGN POLICY DURING THE ADMINISTRATION OF CARDINAL FLEURY, 1726-1743. A STUDY IN DIPLOMACY AND COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT.

November 1936 By John G. Gazley -

Books

BooksTHE UNITED NATIONS IN ACTION

March 1951 By JOHN G. GAZLEY -

Books

BooksTHE MRP AND FRENCH FOREIGN POLICY.

APRIL 1964 By JOHN G. GAZLEY -

Books

BooksENJOYING IRELAND.

FEBRUARY 1967 By JOHN G. GAZLEY -

Article

ArticleIn Reply to Mr. Qua

June 1940 By Judicial Temperament, JOHN G. GAZLEY

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

June, 1923 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

MARCH 1967 -

Books

BooksHUGH LOFTING'S TRAVELS OF DOCTOR DOLITTLE.

JANUARY 1968 -

Books

BooksTROUT FISHING

June 1950 By Albert H. Hastorf -

Books

BooksAMERICANA – BEGINNINGS.

October 1952 By Harold G. Rugg '06 -

Books

BooksAN ASTRONOMER'S LIFE

December 1933 By L. B. R.