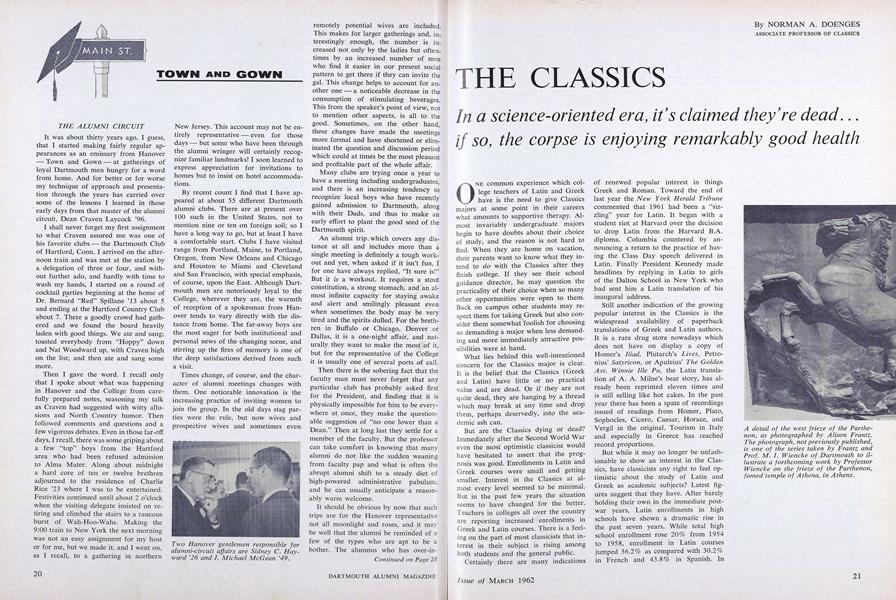

In a science-oriented era, it's claimed they're dead... if so, the corpse is enjoying remarkably good health

ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF CLASSICS

ONE common experience which college teachers of Latin and Greek have is the need to give Classics majors at some point in their careers what amounts to supportive therapy. Almost invariably undergraduate majors begin to have doubts about their choice of study, and the reason is not hard to find. When they are home on vacation, their parents want to know what they intend to do with the Classics after they finish college. If they see their school guidance director, he may question the practicality of their choice when so many other opportunities were open to them. Back on campus other students may respect them for taking Greek but also consider them somewhat foolish for choosing so demanding a major when less demanding and more immediately attractive possibilities were at hand.

What lies behind this well-intentioned concern for the Classics major is clear. It is the belief that the Classics (Greek and Latin) have little or no practical value and are dead. Or if they are not quite dead, they are hanging by a thread which may break at any time and drop them, perhaps deservedly, into the academic ash can.

But are the Classics dying or dead? Immediately after the Second World War even the most optimistic classicist would have hesitated to assert that the prognosis was good. Enrollments in Latin and Greek courses were small and getting smaller. Interest in the Classics at almost every level seemed to be minimal. But in the past few years the situation seems to have changed for the better. Teachers in colleges all over the country are reporting increased enrollments in Greek and Latin courses. There is a feeling on the part of most classicists that interest in their subject is rising among both students and the general public.

Certainly there are many indications of renewed popular interest in thing's Greek and Roman. Toward the end of last year the New York Herald Tribune commented that 1961 had been a "sizzling" year for Latin. It began with a student riot at Harvard over the decision to drop Latin from the Harvard B.A. diploma. Columbia countered by announcing a return to the practice of having the Class Day speech delivered in Latin. Finally President Kennedy made headlines by replying in Latin to girls of the Dalton School in New York who had sent him a Latin translation of his inaugural address.

Still another indication of the growing popular interest in the Classics is the widespread availability of paperback translations of Greek and Latin authors. It is a rare drug store nowadays which does not have on display a copy of Homer's Iliad, Plutarch's Lives, Petronius' Satyricon, or Apuleius' The GoldenAss. Winnie Ille Pu, the Latin translation of A. A. Milne's bear story, has already been reprinted eleven times and is still selling like hot cakes. In the past year there has been a spate of recordings issued of readings from Homer, Plato, Sophocles, Cicero, Caesar, Horace, and Vergil in the original. Tourism in Italy and especially in Greece has reached record proportions.

But while it may no longer be unfashionable to show an interest in the Classics, have classicists any right to feel optimistic about the study of Latin and Greek as academic subjects? Latest figures suggest that they have. After barely holding their own in the immediate postwar years, Latin enrollments in high schools have shown a dramatic rise in the past seven years. While total high school enrollment rose 20% from 1954 to 1958, enrollment in Latin courses jumped 36.2% as compared with 30.2% in French and 43.8% in Spanish. In 1954, 6.9% of all high school students were enrolled in Latin courses. In 1958 that figure had grown to 7.8% with a total Latin enrollment of 618,222. In 1958, 6.1% of all high school students or 480,347 were taking French, 8.8% or 691,931 Spanish, and 1.2% or 97,644 German. The increase in the percentage of enrollment in Latin courses from 1954 to 1958 was practically double the increase in the other languages. High school teachers indicate that this trend has continued. They feel that more recent figures would show even larger gains for Latin.

The situation at the college level is somewhat harder to assess because of the lack of significant course enrollment figures. Available statistics, however, indicate grounds for optimism. While total college enrollment grew 34% from 1955 to 1959, the number of graduates with a B.A. in Classics rose from 512 to 705 or 38%. In French the number grew from 1279 to 1662 or 30%, in Spanish from 1206 to 1444 or 19.7%, and in German from 315 to 501 or 59%. Most classicists feel sure that the picture today is much brighter than it was in 1959.

WHAT these figures imply for the future is at this point hard to say. Classicists sometimes talk in terms of a rejuvenation of classical studies in America. But at the moment it would be unwise to be too sanguine. Certainly, however, the figures are encouraging. They may suggest that the wave of the future need not be against the Classics in spite of the demands of a crowded and often glossy curriculum on the student. But classicists are painfully aware of the precariousness of the Classics' position especially as pressures mount to meet shortterm educational goals and to train students in skills which seem at the moment vitally necessary rather than to educate them broadly.

There is perhaps no ready explanation for this recent surge of interest in the Classics, but certainly some of the credit must be given to the classicists themselves. They have come to realize that the Classics will not automatically be perpetuated without determined effort on their part. Being themselves keenly aware of the importance of the Classics, they are not prepared to see Greek and Latin studies relegated to a corner of the curriculum. In many institutions classicists have become outspoken defenders not only of the Classics in particular but of humanistic studies as a whole. Much greater effort has also been made in recent years to reach the general public. In large cities classicists such as Prof. Gilbert Highet of Columbia have done much to stir popular interest in things classical. Books of a more general nature like Arnold Toynbee's Hellenism or C. M. Bowra's The Greek Experience, not to mention the lively, modern translations of Greek and Latin authors, have also done much to make the public more conscious of the importance of the Greeks and Romans.

One other factor which has helped stir interest in the Classics and inject new life into them is the exciting changes which have taken place within the field itself. In the past seven years the decipherment of the Cretan Linear B script, for instance, has literally opened up the study of the Bronze Age in Greece. New and dramatic archaeological discoveries are forcing classicists constantly to revise their presuppositions about the Greeks and the Romans. In literary studies thanks to the application of modern critical techniques even the standard works have taken on new meaning for scholars and students alike. The Classics as a discipline are probably more alive today than they have ever been.

But perhaps most important are the positive steps which college classical departments have taken to reevaluate the role of the Classics in the curriculum and to devise programs which reassert their position as a basic discipline within the humanities. Classicists have seen that it is not enough simply to train a handful of students to become professional scholars in their field, although this duty must not be neglected. They have come to recognize that at the undergraduate level they have an equally important and indispensable job to perform which only they can do. They must explain, elucidate, interpret the achievements of the Greeks and the Romans for the general student, provide the necessary classical background for profitable work in other disciplines, and spread an understanding of the classical world which will make more intelligible the modern. In pursuing these objectives, classicists see the opportunity of returning the discipline to its rightful place within the curriculum.

But if the Glassies are to play such an interpretive role teachers of Latin and Greek realize that they must broaden their appeal. The result has been a flurry of activity in recent years in both schools and colleges to revise curricula, remodel courses, and experiment with new methods of teaching both the languages and the Classics generally. Examination of curricula and teaching methods has been particularly strong in the secondary schools. But at all levels teachers have become more aware of the wider role the Classics can play. Almost certainly the effort they have expended has contributed to the resurgence of Greek and Latin in both the schools and colleges.

ONE such attempt at remodeling the Classics curriculum was made at Dartmouth last year when a new Classics program was approved by the faculty. The Department had two aims: first, to make more attractive the study of Latin and Greek at the College by adjusting the language program to the needs and interests of the present-day student and, secondly, to give students through courses in translation a broad understanding of the classical world, its literature, history, art, government, and thought.

Changes introduced in the language program of the Department were mostly ones of emphasis. For many years the Department has been experimenting with new ways of teaching Latin and Greek. The new program is designed to put into effect the results. Its primary goal is to introduce students as rapidly as possible to the rewarding experience of reading Greek and Latin works as literature. At the elementary level time spent on grammar and drill has been reduced to a minimum. In Greek the general introduction to the language which used to be spread over the greater part of a year is now confined to a single ten-week term. Thanks to new methods the student is ready at the beginning of his second term to read and appreciate Plato. He then goes on, still in the second term, to a play of Euripides, reading which he used not to do until the end of his second year of Greek. The Department believes that after three terms of elementary work the student can with concentration and effort read profitably whatever he likes in Greek. He is free to elect, if he wishes, any advanced course.

In Latin the same approach is used. Students who have had a minimal exposure to Latin in school are now reintroduced to the language by way of reading and immediate use of the language. Almost no time is devoted to formal grammar drill. The content of the elementary courses has also been changed. Instead of the standard fare of Caesar and Cicero, elementary students are exposed to Catullus, Ovid, Horace, and Vergil, poets who speak more directly to the undergraduate and whose works provide a more immediate literary experience. Because of these new methods it has been possible to eliminate at the freshman level a full course in beginning Latin. Students who wish to start Latin in college are enrolled in a special course designed to cover work which had previously taken two terms of study.

At the advanced level in both languages there has been a similar change in emphasis. Gone to a large extent is the worrisome attention to philological detail. Students are now asked to examine so far as possible the literary aspects of the works read. Every effort is made to help them gain a sound critical appreciation of what they are reading.

Why these changes have been introduced in the language program is not difficult to explain. Certainly the main reason for studying Latin and Greek is to be able to read the literature which was written in those languages and to study the classical world more closely than would be possible without the primary linguistic tools. But because of the difficulty of the classical languages it has always been easy for the teacher to pay too close attention to them for their own sakes. It is perhaps safe to say that the present-day undergraduate is not content to regard the study of a language as an end in itself, nor at the undergraduate level should he be asked or forced so to narrow his interests. The Department at Dartmouth and most other classicists realize that the Classics will remain an acceptable major for undergraduates only if they do the job which as a humanistic study they are suited to do, namely, extend and deepen a student's experience in some significant way. The aim of the Department is to develop the study of classical literature as literature and not just as a complicated, though often challenging, mental exercise.

Along with the changes in the language offerings the program of Classics-in-translation courses was thoroughly revised. The departmental offerings were diversified with the intention of presenting a progression of courses on the classical world designed to meet the needs of undergraduates in a liberal arts college.

Accordingly, the standard classical civilization courses at the introductory level were amalgamated, and they were oriented more specifically toward literature. They have become largely surveys of Greek and Latin literature in translation where major attention is paid to the form and content of the works read. The rest of the program was extended to include courses in Greek and Roman history, Greek and Roman art and archaeology, Greek and Roman drama, classical mythology, and classical government.

At the same time a new major was introduced to bring the Classics within the reach of the general student. Instead of devoting all of his time to the study of Greek and Latin authors in the original, the student in the new major is asked to" take only six courses in the languages and then to select three courses from among the departmental offerings in translation. The new major is called Greek and Ro- man Studies to distinguish it from the regular Classics major which requires usually five courses in Greek authors and four courses in Latin authors above the introductory level.

How successful has the new program been? It is still too early to say since it has been in effect for only one full term. There are, however, some encouraging signs. This year beginning Greek was elected by thirteen students, more than twice the number which had been taking it in previous years. There are already eight students signed up for Greek 80, a seminar in Thucydides, to be offered in the Spring Term.

In spite of the elimination of a beginning Latin course freshman Latin elec- tions have held steady. At the upperclass level, however, the change has been spectacular. This term seventeen students are participating in a seminar on Vergil, Latin 80. Five years ago the Department would have considered it unusual to have five students in such a course. Ten students have elected a seminar in Cicero in the Spring Term.

One interesting trend is that such upperclass seminars are being elected increasingly by non-Classics majors. The reason is that students in appreciably larger numbers are continuing their study of Latin beyond the introductory level. Still others are trying Greek with the intention of reading Homer, Sophocles, or Plato in the original. Very often this latter group has already had some Latin and was attracted into Greek after taking the survey course in Greek literature in translation. The Department, needless to say, is encouraging this trend even if the student can afford to take only one or two terms' work in languages. It is firmly convinced that the careful reading of a single author in the original is considerably more valuable for a student than covering the waterfront in translation.

The number of students majoring in the Department has kept pace with growing elections in upperclass courses. This year six students signed up as majors, a number which at first blush may seem small but which in fact exceeds the total number of majors registered with the Department in the previous ten years.

Because of staffing limitations the Department has not been able to put the Classics-in-translation program fully into effect. It is offering this year courses in Greek and Latin literature in translation, Greek and Roman history, Greek and Roman archaeology, and classical drama. The number of inquiries, however, indicates that interest is running high in such courses as Greek Mythology and Ancient Government which have yet to be introduced.

WHAT about the future? What are the prospects that interest in the Classics will continue to grow? If high school Latin enrollments continue to increase at the rate they have set in the past five years, prospects seem reasonably bright at the college level. But current emphasis, fostered by the Conant reports, on the development of four-year modern foreign language programs in the high schools does not bode well for Latin studies. At the moment more than 95% of the students taking Latin in high school do not continue beyond the second year, not because they would not like to go on but because only two years of Latin are offered. Moreover, pressure from school boards and educationists on the high schools to eliminate Latin altogether is growing.

One factor working in favor of the Classics at all levels is the increasing respect being shown the "hard" subjects. Latin and Greek have always flourished when it was not considered odd to be intellectual or learned. Because of the present world situation there are signs that American education may be returning to fundamentals and lopping off the frills which have distracted it for so many years. Only a few months ago historian Samuel Eliot Morison of Harvard, in a pamphlet on The Scholar in America, recommended "a return to the principle that every boy and girl must have at least four years of a foreign language - preferably Latin or Greek - and mathematics through algebra to enter college." He added, "No substitute for Latin, Greek, and Mathematics has ever been found, either for their content, for communicating the best thought of the world, for making modern languages easy to learn, or for training the mind in accuracy and perception." A similar recommendation was made not long ago by Thomas M. Cooley III, Dean of the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, in the Saturday Review. Such straightforward talk by scholars outside the field of Classics may eventually have some effect.

The picture at Dartmouth may be brighter than it is elsewhere. In recent years the number of students with superior Latin training admitted to the College has grown enormously. Three years ago the score on the standard aptitude test which would satisfy the College language requirement in Latin was raised from 600 to 650. In 1959 only seven freshmen scored over 650 and were exempted from the elementary courses. Last year 33 students satisfied the College requirement in this way. Not surprisingly it is from these students that the present Classics majors were largely recruited. The fact that students of higher caliber have been coming to the College has clearly worked in favor of the Classics.

But most classicists recognize that there is an enormous job still to be done if the Classics are to remain an important and influential part of the educational picture in America. One major task which classicists must undertake is to inform about the Classics - not so much students who, once involved in a good Classics course, seem to understand their value, but parents, guidance directors, and professional educationists who have convinced themselves that there is no need or room for the Classics in the modern curriculum. Until those who influence student decisions understand more fully what constitutes a truly liberal and humanistic education, teachers of Greek and Latin will continue to be cautious in their predictions about the Classics.

A detail of the west frieze of the Parthenon, as photographed by Alison Frantz.The photograph, not previously published,is one of the series taken by Frantz andProf. M. I. Wiencke of Dartmouth to illustrate a forthcoming work by ProfessorWiencke on the frieze of the Parthenon,famed temple of Athena, in Athens.

Matthew I. Wiencke, Assistant Professor of Classics, makes use of the DartmouthMuseum's pottery collection in his winter-term course in Greek archaeology.

John W. Zarker, Instructor in Classics,meets with one of his Greek students inthe Department's Dartmouth Hall center.

THE AUTHOR: Prof. NormanA. Doenges, who is Chairman ofthe Department of the Classics,came to Dartmouth in 1955 afterteaching previously at Princetonand the University of Georgia.A graduate of Yale in 1947, hereceived a B.A. degree fromBalliol College, Oxford, in 1949,attended the American Schoolof Classical Studies in Athens in1951-52, and took his Ph.D. atPrinceton in 1954.Professor Doenges directedthe studies leading to the recentrevision of the Classics curriculum at Dartmouth. Active inmany phases of campus life, hewas the first faculty resident ofBrown and Little Halls, serveson the Committee on Admissions and the Freshman Yearand the Committee on StudentResidence, and was a memberof the Trustees Planning Committee sub-group studying admissions and financial aid.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature...AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

March 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Debaters Are Arguing Themselves Into National Renown

March 1962 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

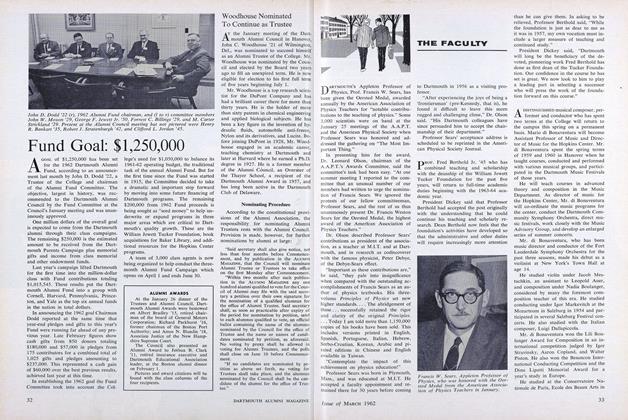

FeatureFund Goal: $1,250,000

March 1962 -

Feature

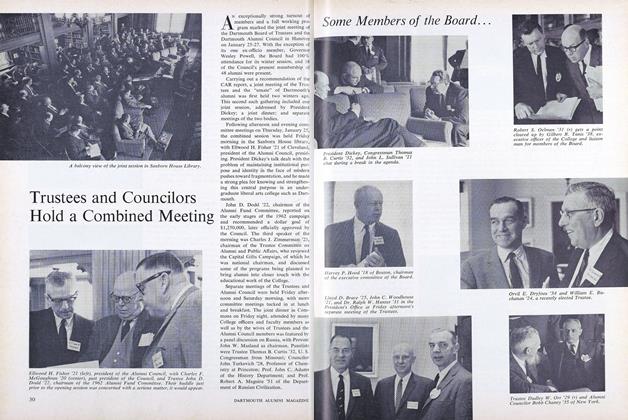

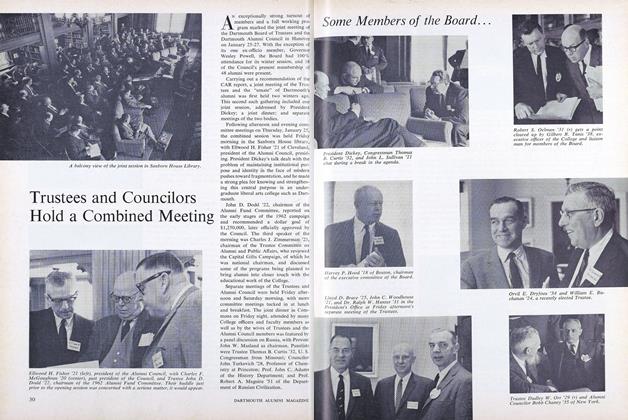

FeatureTrustees and Councilors Hold a Combined Meeting

March 1962 -

Feature

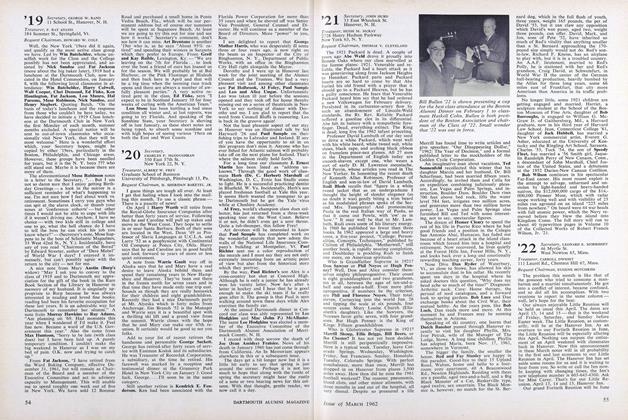

FeatureSome Members of the Board...

March 1962 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

March 1962 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARROLL DWIGHT, EUGENE HOTCHKISS

NORMAN A. DOENGES

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryKevin Ritter '98 Lloyd Lee '98, Brad Jefferson '98

OCTOBER 1997 -

Feature

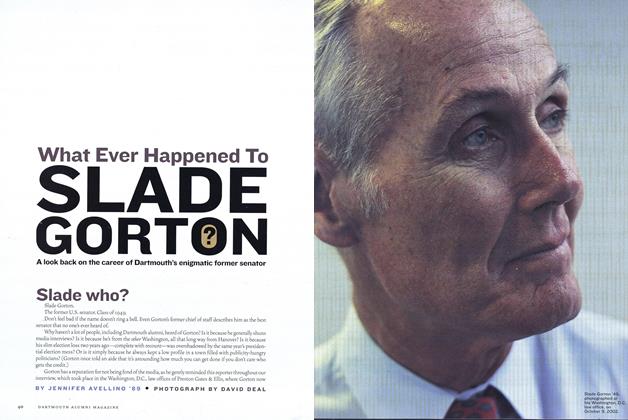

FeatureSlade Gorton

Jan/Feb 2003 By JENNIFER AVELLINO ’89 -

Feature

FeatureGames Changers

Jan/Feb 2010 By LISA FURLONG -

Feature

FeatureThe Dictionary's Function

May 1962 By PHILIP B. GOVE '22 -

Cover Story

Cover StorySolitary Family

MARCH 1995 By Rabbi Robert Schreibman '57 -

Feature

FeatureNew Environmental Studies Program To Be Launched in the Fall

JUNE 1970 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40