Dartmouth's Debaters Are Arguing Themselves Into National Renown

March 1962 HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21Daniel Webster Would Be Pleased

To a college man the informal "bull session," as a mental excitation, has always been a part of campus life. It flourishes luxuriously in the dormitory, the social hall, the fraternity house - generally after the books have been put away for the night, and the minds of the participants have not quite unwound. It covers any piece of business under the sun - can be listened to indulgently or engaged in with life and spirit; can be intruded upon abruptly or boycotted insultingly. Its subjects can be logical or superficial, timely or dog-eared, its temper mild or fierce. It serves many times as a safety valve for those who are too timorous to express their ideas in the public forum, or in a "letter to the editor."

Most of these discussions come to no satisfying conclusion, but are laid down like a book, to be picked up on the morrow. A proponent can change his spots and suddenly become an opponent, at which point he may be violent in the opposite direction - like a hurricane swinging around from one point of the compass to the exact opposite. Such a tendency does not indicate fickleness. It just means that the parties involved like to "argufy" for the sake of logomachy. (Look it up! We did.)

For those who wish to put such innate ability to good purpose, to develop directness of thought, cogent reasoning - as opposed to forcible reasoning, which may tell strongly but not convince - there is a campus organization at Dartm outh called the Forensic Union which has transformed the rowdy sport of stormy debate into the delicate art of rhetoric.

Long past are the days when a "debating team" had both a defensive squad and one for the offense. Today the team plays both roles, and its members must be adept on both sides of a question. For reasons of efficiency and economy, the home-and-home schedule with only two or three teams involved has given way to massive competitions with up to forty teams involved, operating through a two or three-day period.

The better known of these competitions are the West Point National Debate Tournament, the Notre Dame National Invitational Tournament and, more locally, the Dartmouth National Invitational Tournament.

Gone, too, is the multi-subject schedule, with the squad working vigorously one week on a subject such as "Colonialism in Etna" and the following week on "Does Coeducation Lead to a Year-round Fort Lauderdale?"

The subject for a current year is decided upon by the Committee on Intercollegiate Debate Topics, which is an arm of the Speech Association of America. This committee polls its collegiate members annually for subject suggestions. Finally, five subjects which seem to be uppermost in the existing thinking are selected, and the group members are invited to give a relative rating to each. The Committee is then able to announce what the whole membership will use as a resolution for discussion, at all meetings scheduled for the ensuing winter and spring.

SKETCHES BY ROBERT GREENWOOD '63

For 1962 the topic has been "Resolved: That Labor Organizations Should Be Under the Jurisdiction of Anti-Trust Legislation." In 1961 the subject was "Should We Have Compulsory Health Insurance?" The four subjects for 1962 that went into the discard were (a) Should Red China Be Admitted into the United Nations? (b) Should There Be Compulsory Arbitration in the Interna- tional Court of Justice? (c) Should the House Committee on Un-American Activities Be Abolished?, and (d) Should the United States Adopt the Policy of Aggressive Action?

These resolutions are, admittedly, more cosmopolitan in flavor than the subject selected in 1788: "Should the time spent in studying Greek be more profitably spent in studying the French language?"

At one time in the mid-1860's the debating clubs were so hard put for subjects that we find one question used - never suitably concluded - "Where does the fire go, when it goes out?"

It is interesting to trace through the history of the College the various organizations that carried the aegis of sophistical reasoning. In the program of the first Dartmouth Commencement, on August 28, 1771, there is listed a Syllogistic Disputation, wherein Samuel Gray held the question "An vera Cognitio Dei Luce Naturae acquiri potest?" He was opposed by Levi Frisbie, John Wheelock, and Sylvanus Ripley. These four gentlemen, by the way, comprised the entire roster of the graduating class.

The Phi Beta Kappa Society, established at Dartmouth in 1787, held meetings on alternate Thursdays, with the usual exercises "comprising a dispute by four persons, two speaking from manuscript and two extempore, on the same question." The subjects were of a worthy character, the nearest approach to levity being a solemn discussion of a constitutional question as to the heating and lighting of the hall. On this timely topic it was decided, after long debate, that the treasurer might, without endangering the constitution, furnish the requisite fire and candles.

In 1827 Phi Sigma was formed and designated as an "assembly of debaters." About this period, the sophomore class sustained for several years a burlesque moot court, which according to Chase's History "afforded great amusement and also much improvement in debate and the knowledge of the forms of law."

The Antinomian Society, organized in 1841, met weekly and included in its agenda "an extempore debate by four disputants, to each of whom was allowed fifteen minutes, and to volunteers ten minutes." This group lasted exactly fourteen months and eight days and was merged with Gamma Sigma in March of 1843. But this amalgamation likewise disappeared in the early winter of 1845.

Commencement exercises throughout the early 1800's included not only the valedictory and salutatory addresses, as a part of high scholastic recognition, but also a philosophic oration, a Greek oration and, seventh on the list, "Disputations." By 1865 this subject had risen to fifth in order of rank, with three disputations being offered, each with two speakers.

In November of 1865, Professor Edwin D. Sanborn, as head of the Rhetorical Department, proposed the revival of Quarter Day, marking the ending of each quarter of the college year. The schedule of events included a debate between two persons, "one Social and one Frater."

At about this time the Rhetorical Department of the College was bolstered by the engagement of Professor Mark Bailey, Class of 1849, as instructor in elocution. He came to Hanover from Yale University each fall for a six-week period, until the year 1876, and "exerted a strong and helpful influence upon the College in the matter of public speaking." However, a reversion to more sophomeric frivolity took place in 1875 when spelling matches became the fad of the winter throughout all the New England colleges.

All through the century there appear in the records scraps of information concerning forensics as an official and important activity of the College. The Rev. Charles B. Haddock, nephew of Daniel Webster, was elected professor in the chair of Rhetoric and Oratory in 1819. Composition and Declamation was listed as a required course in the first catalogue of the College published in 1822. This was to be taken for three years, followed by Dissertations, Forensic Disputes, and Declamations in the senior year.

Haddock was superseded by David Peabody, Class of 1828, followed in succession by Samuel G. Brown, Edwin D. Sanborn, and finally Charles F. Richardson, Class of 1871. "Clothespins" Richardson enjoyed high popularity among successive generations of undergraduates until his retirement in 1911. His field of endeavor during this lengthy tenure was broadened, however, to embrace other activities in the field of English.

We can sense throughout the last half of the 1800's a changing pattern in the educational program. There was the intrusion of the sciences, brought about by the ascendancy of the Medical School, the growth of the Chandler School, the establishment of the Thayer School of Engineering, and the Agricultural College which existed as an entity from 1868 to 1893. These all tended to dilute the importance of the forensic art until it finally retrogressed to the point of becoming a minor arm in the general field of English, extremely elective, in place of the "required" prominence it once held.

TODAY, the activities in forensics have become separated from the formal academic life of the College, and are now almost completely extracurricular. Although its members may be found quite often as leading participants in the official events of the College, such as Commencement and Wet Down, the Union's activities now come within the scope of the Council on Student Organizations. From this latter it derives its authority to use the name of the College and also certain of the funds necessary to meet its expenses. Its membership is open to the entire undergraduate body, and its roster averages about sixty men paying annual dues of $10.

As the fall season progresses the active members begin to warm up to their work, and start the tiring research that is involved in uncovering and exploring all the facets of the subject chosen for the year. Many, many hours of reading and note-taking. The sifting of salient points from the chaff. And then, after each debate, long discussions as to new points to be introduced, old points to be strengthened or discarded.

A card file is maintained on the annual subject, replete with "evidence" that can be offered in exhibition as both pro or con to the subject. This file is continually revised as old supporting statements increase in value and others begin to lose their charm. This box of cards is literally the fount of knowledge which springs eternal to bring new and refreshing draughts to the jaded minds of its partakers.

Formal presentations are made from carefully prepared cue cards, but of course the rebuttals have to be extemporaneous. It does not take many sessions to derive advance knowledge on what points need "rebutting," but each time there must be on-the-spot choices of which verbose giants of the opposition to knock over, and which suddenly appearing ghosts to be stripped of their eerie semantic garments.

Strangely enough, few members of the Union take advantage of the undergraduate courses offered by the Speech Department. After all, how can four hours of classroom work for nine or ten weeks of a term compare in effectiveness with hundreds of hours spent in the informal coaching and discussion sessions? The time thus expended may even exceed the hours which these team members devote to their major subject, which is generally English.

Too much credit for the ongoing success of the Forensic Union teams cannot be given to the faithful sponsorship of their programs by the Speech Department, and especially Prof. Herbert L. James, coach of debate. On him rests the load of carrying the squad from one season to the next, helping to draw the threads of nebulous facts and fancies into a strong fabric of cloth that will hold water, listening to and coaching the team members as they present their arguments in practice sessions, traveling with the groups as time and finances permit, and checking the myriad details concerned with the home activities. It is a toilsome task which Professor James handles with personable and unflagging grace, and for which his recompense is mainly pride of accomplishment and the lasting friendship of "his boys."

From the time when the teams first started to travel far afield, expense has been a major consideration. There was the time when, in the coach's car, the squad traveled all night, in winter, alternating drivers, to reach the Northwestern University campus at Evanston. Then came 48 hours of debate mixed with a modicum of sleep and food. On the return trip, the squad endured another night of treacherous driving, reaching Hanover dead-tired by Sunday afternoon. That expedition was the denouement. From that day on it was unanimously decided that the travelers would leave the driving to someone else.

Today they jet to Chicago, South Bend, Abilene, Lawrence, Washington, Morgantown, and Redlands. This means added expense, but timely and unexpected financial aid from one interested alumnus has solved the problem for the 1962 season. Would that there could be more like him!

In 1962 the varsity trips of the Forensic Union will cover about 45,000 miles, as the crow flies. All dates cover multiple entries, with as many as fifty schools participating in some events. What other college activity can lay claim to such

In February, Dartmouth played host to about 45 varsity teams, with only two colleges sending their regrets. Over three hundred team members and coaches threw themselves on the hospitality of the Hanover plain. This required many hours of work to locate housing, arrange meals, meeting rooms and transportation, along with the myriad of detail that goes with such an influx of declamatory talent.

To encourage debating at the secondary school level the Union is sponsoring for the thirteenth year the Annual Debate Tournament for New England High and Preparatory Schools. This project started in 1949 with nine high schools participating, and has grown to the point where, in 1962, there are fifty schools represented from New England and New York State.

The highlight of the year is the Annual Spring Banquet held during the first week in May, when prizes and awards are made to members of the Union.

The highest single honor given at that time carries with it life membership in Delta Sigma Rho, the national debating fraternity. It is available to any senior who has debated "actively and successfully" for three years.

The Lockwood Debating Prize, a cash award, goes to the outstanding debater of the year. Equally sought after is the Brooks Cup, presented to that member who has "done the most to advance the cause of debating." This stipulation renders the Cup available to men who may have run second or third in many of the verbal races, but whose devotion to the group through efforts in research or moral assistance has enhanced their value to the team.

IT is too early, as this is being written, to report on the assured success of the 1962 schedule, but a few statistics on the 1961 season will indicate the reason for the high esteem in which the Dartmouth Forensic Union finds itself held in collegiate circles. In 280 presentations by the varsity squad there were 178 wins for a percentage rating of .677. In the novice competitions the percentage rating was .659. Four varsity men won thirty or more contests, and six had winning percentages higher than .700. Four men acquired memberships in Delta Sigma Rho, with five more winning varsity keys.

In 24 varsity tournaments the Dartmouth squads took five firsts and three seconds, with six more ratings in the third, fourth or fifth spots. In a total of 368 debates (both varsity and novice) there were a total of 236 wins for a percentage of .672. Thirty-seven men participated against 144 schools representing 33 states, plus the District of Columbia and the British West Indies. In Ivy League competition (against Harvard, Princeton and Cornell) the score was 5 to 3 in favor of the Green. Their worst defeat (shades of football) was at the hands of Holy Cross 2 to 8. King's College and Duke also were disastrous opponents.

A study has been made of the impact which former polemical gladiators have made in the world of national politics and jurisprudence. Since 1900 there have been 530 Dartmouth graduates who engaged in forensic activity during their undergraduate years. Of these 66.6% acquired advanced degrees, of which 178 were in the field of law. All but 21 of these latter became lawyers and/or judges.

Whether the group had superior intellects because of their academic exposure, or whether only men of high scholastic standing choose the activity of debating, is anyone's speculation. But it suffices to report that of the 530 participants 61% were in the top third of their class and 30% were Phi Beta Kappa, with 44 more achieving honors of summa cum laude, magna cum laude, or cum laude.

Here are the culminating achievements of some of the individuals involved in this statistical report: State Supreme Court Justice, several college or university presidents, many trustees of educational institutions, president of the American Bar Association, president of the American Red Cross and the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, dean of a school of religion at a large state university. Besides these specifics, there has been good representation in the higher echelons of state and city governments. Unrelatedly there have arisen such prominent figures as president of one of the country's largest public utility companies, a leading American novelist, the builder of the world's largest bridge, and a Secretary of the United States Navy.

It may well be asked, what does all this enterprise mean to the College - and to the participants? To the College it is giving untold publicity of the most favorable sort, at sister institutions and in their

communities. It is bringing recognition to the broad, liberal learning that Dartmouth makes available. Although the Forensic Union's rave notices are limited mostly to the collegiate press, its accomplishments are being widely recognized in all academic circles.

To the team members the experience brings poise, self-assurance, synthesis, judgment, decisiveness. They gain these qualities for their benefit in post-graduate life. They are prepared to embark upon careers which' call for contact with the world public, where their articulate powers can be used to project logical ideas and conclusions to the democracy. This kind of ability is more of an influence in today's society than any other factor, not excepting the military. Witness what demagogues are able to do with their subjected peoples through their harangues, pointless as they may sometimes seem to be.

It would be well for our country and the world if more young men of the colleges could be encouraged to enter the field of debating. At Dartmouth, this might be achieved if greater support, both moral and monetary, were forthcoming for an endeavor that has achieved a special excellence among all the activities on the campus.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

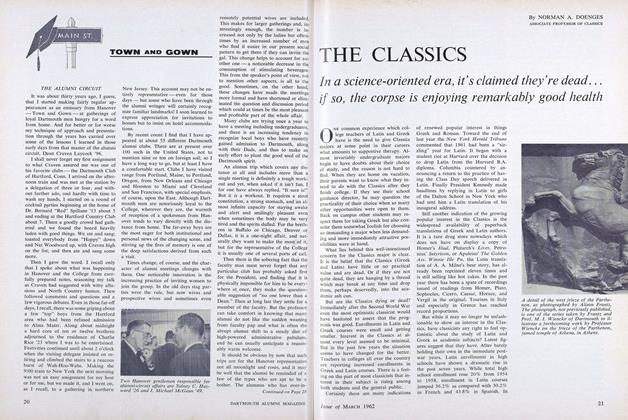

FeatureTHE CLASSICS

March 1962 By NORMAN A. DOENGES -

Feature

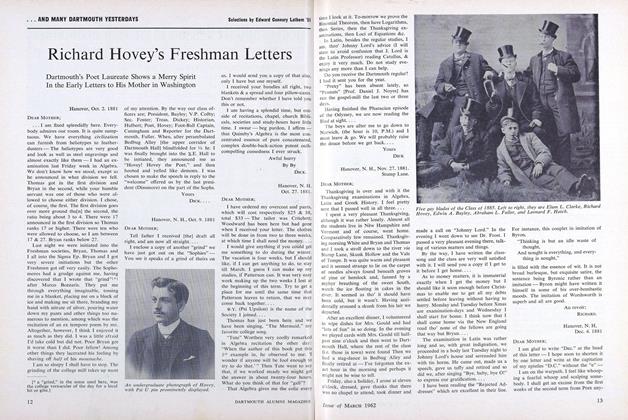

Feature...AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

March 1962 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

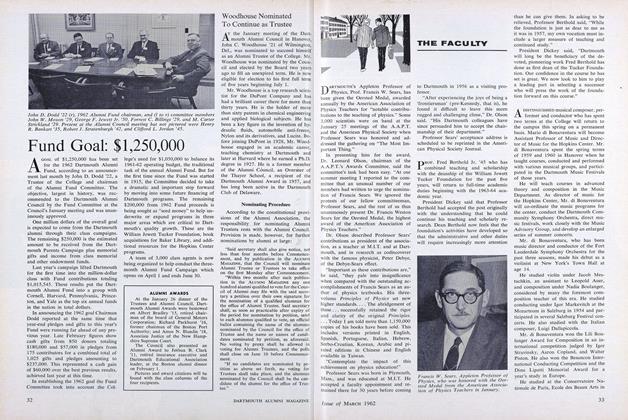

FeatureFund Goal: $1,250,000

March 1962 -

Feature

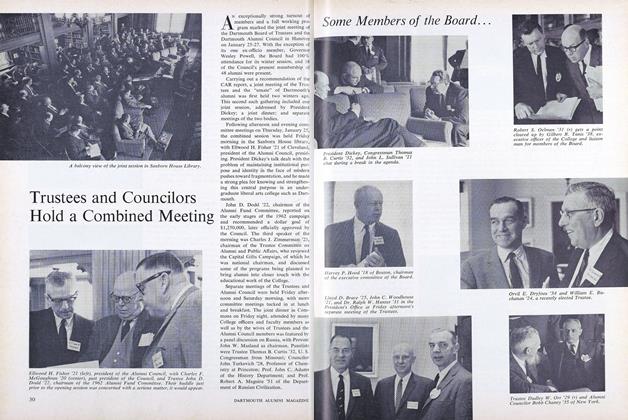

FeatureTrustees and Councilors Hold a Combined Meeting

March 1962 -

Feature

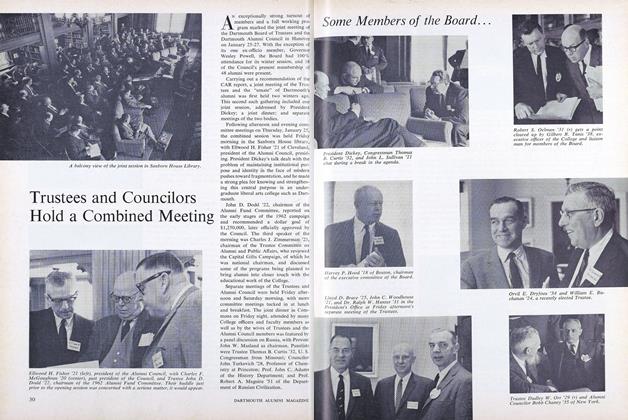

FeatureSome Members of the Board...

March 1962 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

March 1962 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARROLL DWIGHT, EUGENE HOTCHKISS

HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

JANUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

FEBRUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

APRIL 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

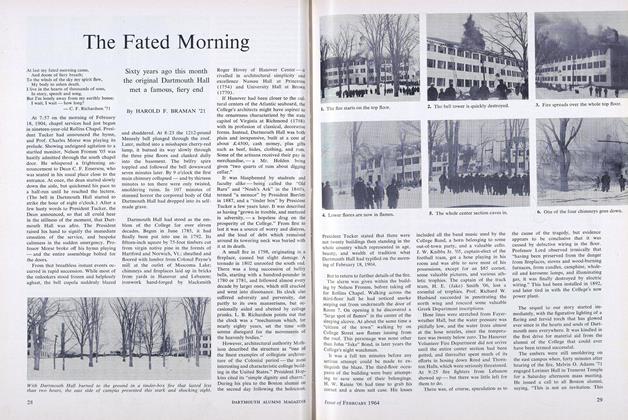

FeatureThe Fated Morning

FEBRUARY 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

APRIL 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45

Features

-

Feature

FeatureChauncey Loomis Professor of English 1,000 agonies in a single sentence

January 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryRobert Harris Upham 1832

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Global Classroom

Sept/Oct 2004 By CHRISTOPHER S. WREN ’57 -

Feature

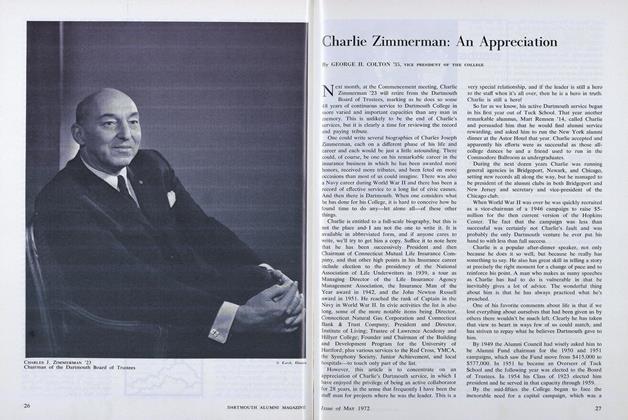

FeatureCharlie Zimmerman: An Appreciation

MAY 1972 By GEORGE H. COLTON -

Feature

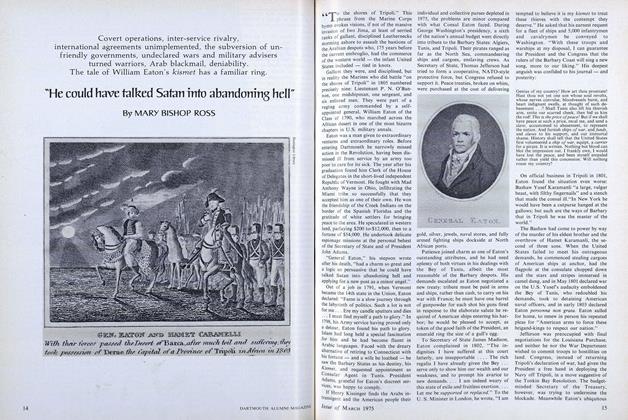

Feature"He could Have talked Satan into abandoning hell"

March 1975 By MARY BISHOP ROSS -

Feature

FeatureThe Dictionary's Function

May 1962 By PHILIP B. GOVE '22