Lew Stilwell

TO THE EDITOR:

Here are a few additional grace notes to the theme of Lew Stilwell: I hope that many others may be collected, and that they will go on crescendo, until we finally have a fulllength biography.

Once in freshman Citizenship class he asked us if we had ever seen anything. We knew him well enough to know that he didn't mean the obvious, even when he followed by asking if we had ever seen Dartmouth College. He had, he said, just a day or so before. He had climbed Velvet Rocks and from there he saw Dartmouth: not just the buildings, and the students and faculty walking to and fro, but the alumni in New York and other cities, and those on their way to Norwich station. Also, all the Dartmouth men who had ever lived, and those not yet born, or just being born.

Teilhard de Chardin writes of seeing things in the dimensions of space-time, and adds that many modern thinkers are not capable of it. But Lew was a seer who could, and it was that four-dimensional quality of his thought which made him so stimulating, and at times mystifying and even provoking.

It was in the spring vacation of 1927 (I think) that Lew hitchhiked to Georgia. When he got back he had a lot to say about swamps. I think he visited the Okefenokee, and it made a tremendous impression on him. What, he asked us, was the influence of the Southern swamps on the Civil War? Once again, we knew him too well to suppose that he meant militarily, or as a place of refuge. He meant psychologically: what was it like to live in such a country, as far removed from the granite of New Hamp shire as anything that Lew had probably ever seen? What was the spiritual and psychological impact of such a landscape on its natives? In those days Lew was constantly ruminating on the Civil War, and I think he took that trip in order to find out what it was like to be a Southerner, a low-country Southerner. He suggested that a whole book might be written on the influence of the swamps of the South, and challenged us to do it. (But I doubt if there have been any takers: Stephen Vincent Benét might have done it.)

In the spring of 1928 my roommate, John Cone Rust, of Cleveland, was drowned in the Connecticut River. His body was not found for a month, and it was Lew who came upon it while paddling. I was asked to identify it for the Grafton County coroner; the spot was inaccessible from the land, and the Dartmouth Canoe Club supplied four canoes and canoeists. It was as solemn a cortege as any the Indians used to stage, with President Hopkins in the bow of the first, Dean Laycock in the second, the coroner in the third, and myself in the fourth. Lew was there to meet us in his own canoe, and gone was all his banter and Socratic dialectic. He could not have shown greater tenderness toward me, for he knew that it was as trying an experience as I had ever had. (I was able to identify John's body only through a signet ring.) Later Lew told me that he was proud of me because of my composure; I think that it was really numbness, but his praise meant a great deal, and helped restore my morale. And when John's parents came on from Cleveland - an even more trying experience, for they had already lost two children - Lew met them and could not have shown greater sympathy. He possessed that rare gift of empathy, but he kept his light hid modestly under a bushel until the occasion came for it to shine out.

Wayside, Md.

TO THE EDITOR:

May I add one footnote to the many memories of "General" Lew Stilwell being mentioned in the MAGAZINE.

It occurred one night as Lew and I were sitting in that Hanover drug store Lew liked so well, elbows propped on the counter in between French fries, catsup, and hamburgers, discussing the world at large and the American government in particular.

"You know," said Lew, "the first revolution in this country was touched off by taxation without representation. The next one's going to be to obtain representation without taxation."

Truer words were never spoken.

Columbia, Mo.

TO THE EDITOR:

Men of Dartmouth; "You paddle bow, and I'll take the stern. . . Bring her up on the beach; you first."

Then the fireside, and eats, and stories, and untroubled sleep, on the island, in the cabin.

That was Lew Stilwell, who first taught me Citizenship.

Franklin McDuffee, all Oxford, made me write good English; but he was from Rochester, N. H., and had a sister in Dayton, Ohio. He played Rimsky-Korsakoff for me, because that was what I could understand.

Walter Brooks Drayton Henderson, whom Johnnie Poor invited to read us his NewArgonautica, leaning on his cane.

W. K. Stewart, the grave, the compassionate, who opened for us all the books of the world.

Louis Silverman, who actually foamed at the mouth over forty minutes and five lines of calculus, and kept us all amazed.

Fred Longhurst, who called us back from the snowy hills in the evening, as he brought the Meneely bells home, through the changes.

Many other quiet ones, whose names I don't recall. One advised me to buy a little book of Greek, with two silver coins on the cover.

Cudworth Flint, who woud say, "What exactly do you mean by that?"

And David Lambuth, who had lived in Brazil.

San Jose, Costa Rica

It's Never Too Late To Study Greek

TO THE EDITOR:

Twenty years out of Dartmouth found me with one regret about the courses I had taken: that I had not studied classical Greek. The reasons for this regret are related to an increasing interest and appreciation of classical civilization as the years have passed, but that is not my story here. The fact is that, goaded by this interest, I finally sat down and started to study Greek. What happens when one starts to do such a thing?

To begin with, the results are gratifying and the effort is enjoyable. To my surprise I find the language not at all difficult. The strange alphabet is a sort of repellent crust to the uninitiated, but it is quickly and easily broken through. Thereafter one is surprised not by the strangeness of one's surroundings, but by the familiarity! Everywhere, in phonology, spelling, morphology, syntax and lexicography, correspondences with English and Latin abound. One is pleased to find oneself learning a good deal about one's own language: where words come from, and so on. Then one realizes that one is gaining a view of the flow of the stream of the Indo-European languages as a whole and is thereby being introduced to the science of philology and gaining a firmer feeling of identity with one's race. All of this is tonic for any inquiring mind.

I have started with a grammar and a dictionary, tools available to anyone, and little other help. There are several good grammars available. Crosby and Schaeffer's An Introduction to Greek is the one I have, and it appeals to me as well arranged and well written. At times, it has raised more questions for me than it has answered. Having no teacher, the obvious recourse was the library where the answers are to be found in books such as E. H. Sturtevant's ThePronunciation of Greek and Latin, C. D. Buck's Comparative Grammar of Greek andLatin, K.T.L.(!) It has been fun to commence to find my own way. The thickets of philology are turning out to be remarkably well-ordered forests. As a result, I am learning that a good textbook is economical instyle and suggestive: it should not lay out allthe answers plainly before the student. To do so only robs him of the pleasure of his own discovery and adds unnecessarily to the already excessive bulk of printed matter.

Back in my college days, E. Rosenstock-Huessy's Latin grammar was extremely helpful to me. It was fresh and different in its approach, therefore exciting. I now find things that I might question or criticize, academically, but it still demonstrates one fundamental characteristic of a valid teaching tool or text: the probing freshness, the difference, the risk which always excites the coming generation.

I write this letter with the sole purpose of encouraging others who may, like me, have had the same inclination to look into Greek. It is worth the look. To date, I have not gone very far, and Lord only knows how far I'll get, but what I've seen so far has been worth the price of admission. Above all, there's no harm in starting alone and floundering around a bit. It may, in fact, be an asset.

Claremont, Calif.

A Service Man's Reply

TO THE EDITOR

I am sending you an article from the Army Navy Air Force Journal and Register of 1 June 1963, dealing with the complaint an unidentified Dartmouth professor made to Senator Norris Cotton about the "enormous pensions" paid to military people.

I am sure that if the "Professor" has not gotten the word by now it certainly does not reflect too well on the teaching staff at Dartmouth. A short talk with any of the ROTC staff at the College would have straightened him out and saved him the trouble of writing to Congress.

Since leaving Dartmouth in 1948 and graduating from the Military Academy at West Point in 1952 I have had to move only nine times with a varying size family now numbering five children. I have been most fortunate in that I have been away from my family only two- or three-month periods at a time and as yet have not been on isolated tours in such lovely places as Greenland and Korea. I am not complaining and I thoroughly like my life and work, but it sorely tries me when someone that should know better and is associated with an institution that X have a great deal of respect and admiration for sounds off in such an uninformed manner.

I think the last sentence in the article pretty well sums it up: "Professor, if you envy the military man his 'enormous' retirement check, why didn't you stay suited up and earn one for yourself?"

Williams AFB, Ariz.

"You've Got Yourself a Home"

TO THE EDITOR:

I would like to report on a recent visit to Hanover: '

Item one—I am a writer (unpublished variety). Working on a book in Mexico, I found myself tired of fighting dysentery and other plagues and decided one night to take a plane to Hanover. Hygienic old Hanover. This was an unusual decision for a person like me because I am not a Reunion Type.

Item two—Having only $1OO left, I figured I was in for a tough time. But an old friend fixed me up with a lovely room. Another friend, one of my former professors, was kind enough to get me a private study room in Baker Library which entitled me to full library privileges. Everyone connected with the Library treated me with great courtesy.

Item three—Deans MacMillen and Chamberlin were also especially kind: card to the swimming pool, use of a night study, and best of all they were friendly.

Item four—The dysentery caught up with me and I found myself in the hospital. If one must be sick anywhere in the U.S., this is the place to do it. Many of the nurses in Dick's House remembered me by name. The doctors were great. I had an air-conditioned private room and people like Tom and Bill, the housemen, around to shoot the bull with. All in all, everybody was damn nice.

Item five—Afterwards , the generous and astute criticism of my work by former professors; the unexpected pleasures of running into old friends who'd drop up.

Item six—You ought to see what they've done with this place. I was surprised to find that Hopkins Center had been built. And it's magnificent! Theater, flicks, concerts, art gallery, food—and because of the coed Summer Session—many lovely young things running around the halls. As an alumnus one normally despises change of any kind. But this is O.K.

Item seven: To sum up, I had a nice summer. And at the risk of being cornball, I'd like to say one more thing. After you've put in your four years here . . . griping and moaning, falling on your ear in the snow . . . you've got yourself a home. I am writing this to thank everyone who's helped to keep this place going.

New York City

"A Great Gentleman"

TO THE EDITOR:

I have this evening just finished reading your well-deserved tribute to Gordon H. Gliddon.

As a Dartmouth parent, Class of '58 and as a follower and supporter of Dartmouth causes for a great many years, even before the great football team that included the immortal "Swede" Oberlander, I was moved almost to tears by your beautiful comments about Mr. Gliddon.

I believe that he was one of those imperishable figures that enter our lives all too seldom. I knew him as a teacher, as a Selectman of Hanover, as an employer of my son for four years in the Library, and as a friend.

He was a great and noble figure in my book. He not only had a "fertile" brain, but it never ceased to learn. There is very little that you gentlemen in Hanover need to know about Mr. Gliddon. However, very few of the parents of students got to know him and his lovely wife, as my late wife and myself had the privilege of doing. We both thought he was a wonderful man and rightly so.

I am reasonably positive that in that great Valhalla that is supposed to be reserved for the great ones in our lives, Gordon Gliddon will not have to approach the Judgment Seat with hat in hand. They will make a place for him, you may be sure!

Rumson, N. J.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

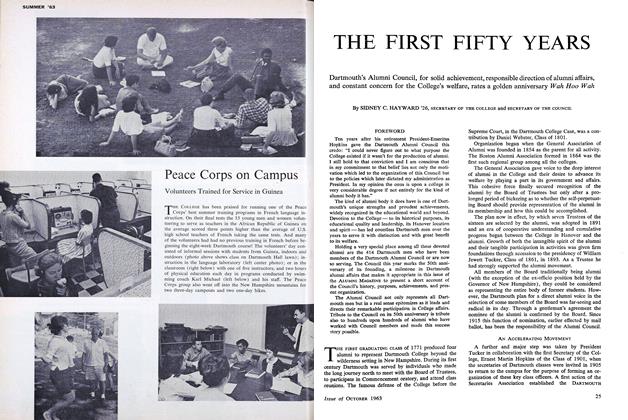

FeatureTHE FIRST FIFTY YEARS

October 1963 By SIDNEY C. HAYWARD '26, -

Feature

FeatureSome Thoughts About Teaching

October 1963 By RAMON GUTHRIE, A.M. '38 -

Feature

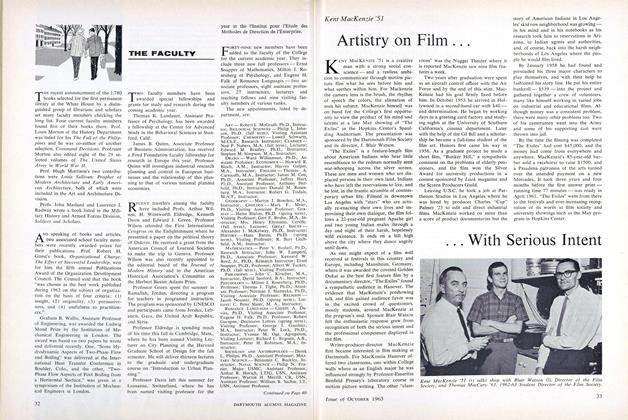

FeatureArtistry on Film ... ... With Serious Intent

October 1963 -

Feature

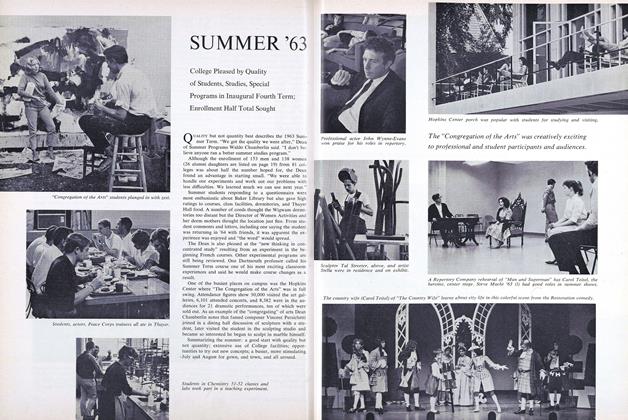

FeatureSUMMER '63

October 1963 -

Article

ArticleDeaths

October 1963 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

October 1963