PROFESSOR OF FRENCH EMERITUS

WHEN. I was at the age of most of the students here tonight, I was a toolmaker — at least that is what my timesheet called me - and was looking forward with less than no enthusiasm to remaining one for the rest of my life. Now that I am arriving at the end of a quite different career, I should like to talk about another toolmaker.

I have in my hand a flint tool that I dug up many years ago in the Dordogne in southwestern France. It is a classical "flake" knife in the shape of a triangular prism, about three inches long and with its lateral surfaces about half an inch wide. Two of its ridges are sharp cutting edges; the other ridge is neatly beveled to fit the user's grasp. It was made some 20,000 years ago by a paleolithic craftsman. He was a man of skill and learning. (As a matter of fact, anthropologists tell us that his brain was larger than our own.) He knew almost everything there was to know - or at least, almost everything that one man could learn from another at the time. He had passed off his language requirement at the age of four or five. In mathematics, he had learned that he had two hands and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 fingers on each, though it is probable that no such higher abstraction as "2 times 5" had ever occurred to him and that there was no word for "times" to enable him to formulate, let alone to pass on, such a concept in any case.

He knew hunting and fishing and firemaking and integral and differential beast-skinning - though, because he was a specialist in toolmaking, he probably didn't spend as much time at these occupations as he would have liked. He didn't know everything about the art of those of his fellow tribesmen who were making magnificent paintings of bison, rhinoceroses, deer and wild ponies on the walls of caves. But, since he was human, he probably thought he did. And almost certainly he used to say with a slightly smug air, "I don't know anything about art, but I know what I like."

He probably didn't know everything that the witch doctor - that interpreter of omens and inventor of taboos - knew. But then, most of what the witch doctor knew was hocus-pocus.

This toolmaker had learned everything worth knowing. Yet, judging if only by the fact that his tools were neater and better made than those of his predecessors a few thousand years earlier, we may guess that he sometimes wanted to learn more.

At convocation when you first came to Dartmouth, President Dickey said, "Gentlemen, your business here is learning." No matter what field you go into, learning will always be at least a part of your business. Man seems to be the only animal chronically addicted to learning. Quite apart from any necessity to learn, he seems to have an inexplicable itch to learn.

What is the fruit of it? In the Book of Ecclesiastes we read, "How dieth the wise man? As the fool, and whosoever increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow." We may feel a sort of waspish satisfaction in knowing that the wise man is no more immortal than the rest of us, but certainly one of the fruits of the acquisition of learning is a sorrowful and profound conviction of our ignorance. At forty we shudder at remembering how ignorant we were at thirty. At fifty the extent of our ignorance at forty makes us squirm. In our sixties we are appalled to find how invincibly ignorant we still are.

Nevertheless President Dickey was right: learning was your business. But it was not your aim. Learning can never be a justifiable aim in itself. The immediate aim of learning is understanding.

MANY of you have decided to become teachers. I congratulate you on your decision. For the most part, it is a very rewarding career. But, as you will, discover, it has its horrendous moments for examplewhen you pick up a final exam written by a hard-working and conscientious student, and find that all he has done is to give you back a faithful, almost verbatim, transcript of your own words. A tape-recorder could have done as much. At such times, no matter how much a teacher may know about his subject, no matter how judiciously he may have weighed his opinions in class, he wishes he had kept them to himself. He feels not only that he has not taught the student anything, but that he has actually prevented him from learning anything. Even worse than that, he feels that he has betrayed the author or authors whose message and vision he was trying to communicate. There are teachers who deserve such misfortunes. Perhaps all of us do sometimes.

Strangely enough, the one teacher who taught me most was in many ways the worst teacher I ever heard of. His subject — in fact, the main interest of his life - was old Provencal, the Langue d'Oc, in which the troubadours wrote. His class was scheduled for 2 o'clock on Tuesdays. But Toulouse was a leisurely town. He seldom arrived before 4 o'clock. When he did get to his seminar room, he would settle down to revising the proofs of an edition of a book that he had been working on for years and which was still unfinished at his death. He was a huge man, slow-moving, slow-spoken, jovial and known to everyone in town as le Pere Anglade. He liked beer and food. He had published many books of quite uneven scholarship. His predecessors in the chair at Toulouse had been distinguished scholars. They had been called to teach at the Sorbonne - which he knew he would never be.

The only way one could drag him away from mulling over his proofs was to ask him questions. Good questions. Easy questions didn't interest him. And hard questions he quite often couldn't answer. It was rather like conducting a quiz program, with the quiz master having to try to answer his own questions.

I would read the passage that puzzled me.

"Hm. Have you looked it up in Raynouard?" he would ask.

I had.

"What about Bartsch?"

Yes, I had looked it up in Bartsch and in Thomas, and Levi, and Mahn and Appel and Chabaneau and Grangent — al the standard reference works on the subject - and could tell him what each of them did or didn't say on the subject. He would lay his proofs aside. "Hm. Well, what's your question again? Let's take a look at it."

I don't remember that he ever did actually answer any of my questions. That was not important. He made me want to go tramping through the country where the troubadours had lived and where, in addition to working out answers to some questions, I took in through the pores an understanding of their work such as I could never have found in books alone.

He had a rare gift for rolling back time, so that, when we talked together of Peire Vidal, Bertran de Born, Marcabrun, William of Aquitaine, these men who had lived seven or eight centuries earlier in places I came to know, became our contemporaries. Incidentally, he brought me to know poets whose work still have a dominant influence on my own poetry. I had already had a variety of teaching experiences dating back to my first year in prep-school, but without what le Pere Anglade did to me, I doubt that I should ever have returned to teaching or at least - since I was taking my degree in law at the time - whether I should ever have taught in the humanities. Without him, I should probably not have become interested in prehistory nor have come here tonight with a flint knife.

WHAT did this man have to give a student? What he had, more than almost any teacher I have ever known, was love. He loved the Provencal tongue. He loved the poets who had written in it centuries ago. I think that what he taught me - to the extent that anybody ever teaches anyone anything - was that, if learning is a means to understanding, understanding is chiefly important as a means to love.

Love is an elusive word. It means all sorts of things - from zero in a tennis score to the vital unifying force that endows life with meaning. Many of the great mystics, Jewish, Christian, Moslem, Hindu, Buddhist and agnostic, have tried to define it. Putting several of their definitions together we may come up with a concept of love as the supreme goal and activity of the Self or Soul. It implies a deep attachment, personal but unselfish, and with overtones of gratitude and awe. For our present purpose, we might stand on St. Paul's statement: "If I know all mysteries but have not love, I am nothing."

Every time I go to Paris, I visit Stendhal's grave. The inscription on the headstone is in Italian. It reads: "Arrigo Beyle, Milanese. He lived, he wrote, he loved."

Now, of course, Stendhal's first name was Henri, not Arrigo; and he wasn't Milanese. But he loved Milan as much as he hated his native Grenoble.

The inscription, as he himself planned it, recorded the fact that he loved Cimarosa, Mozart and Shakespeare. I wish it had been kept that way. The list of what a man has loved amounts to a revealing spiritual biography. Standing beside Stendhal's grave a couple of years ago, I found myself musing on what my own list would be. I soon discovered that, unless the lettering were very small, what I would need would be not a tombstone but a veritable obelisk. It would have to say that I had loved Stendhal and Julien Sorel, Rembrandt, Goya and his portrait of the Marquesa de la Solana, Balzac, Beethoven, Rimbaud, Proust, the architect of the south tower of Chartres, the builders and sculptors of the cathedral at Bourges. Near the top there would have to be room for the name of Francois Villon and Cezanne and Vermeer and Matthias Griinewald, and the Van Gogh who painted 39 crows flying over a wheatfield at Auvers.

About forty miles east of Paris, out in the fields off any main road is the church of Rampillon, built in the 12th and 13th centuries. It is so little known that when I first went there, I couldn't even find a postcard of it. Set into its west portal are statues of the twelve apostles and a Last Judgment. Aside from being a thing of almost incredible beauty, it is one of the finest assertions of simple human dignity that I have ever seen. The anonymous sculptor of Rampillon would be very high on my list.

I could go on for a long time mentioning the names of men to whom I am grateful for having loved and who have given meaning to my life.

Of course any list of this kind will be selective, personal and illogical. One can love neither at will nor according to reason. There are plenty of great artists and thinkers, plenty of great works of art, that I admire but could never love. Victor Hugo, for example. He is a poet of tremendous stature to whom every one of us is indebted at least indirectly, whether we know it or not. But I could no more love Victor Hugo than I could love the Second Law of Thermodynamics. I don't know why. One thing I do know, though, is that, if I had more learning and consequently more understanding than I have, the list of people and things that I love would be much longer and more varied than it is.

As a teacher, I have been very lucky L in that for the most part I have had a chance to teach subjects and authors that I loved. This is as it should be. A teacher, in the humanities at least, is a double-agent, with equal obligation to the men whose work he is teaching and to his students. Teaching is also a chain-reaction affair, particularly if one's students go on to become teachers in their turn and to pass on some of one's own enthusiasms. Stendhal said that it was his ambition to be read in 1935. Perhaps, thanks in part to students of students of students of students of ours he will still be read in 3935. That is a very happy thought.

In hoping that our students may become teachers, we don't necessarily hope that they will go into the academic profession. All men are - or should be - teachers. I am thinking of the retired hardware dealer who used to read Shakespeare to me when I was eight years old. Of the inarticulate painter that I used to go swimming with and drink beer with and who taught me how to look at a painting. I remember the stodgy English business man who was responsible for my enduring interest in Romanesque architecture. And the Wall Street lawyer to whom I dedicated my first book of poems, in gratitude for what he had taught me about poetry. None of these people was conscious of teaching me anything.

But what is teaching? If it were just a matter of imparting information, a machine could do it better. In part, it is a matter of rousing curiosity and enthusiasm. Of course, it is also concerned with developing attitudes, vision and discipline. But it is largely, concerned with causing questions to be asked and answers to be found. When you have children at the "why" age who will ask you such questions as "Daddy, why is water wet?" and "Daddy, why don't dogs have wings?" you will discover that this is at least the most natural pedagogical method.

(As to why dogs don't have wings, you can tell the child that it wouldn't do to have dogs racing along the airlanes barking after planes - although he may balk at the teleological concept that such an answer implies. As to why water is wet - well, that is out of my field.)

The questions need not always to be voiced, but they should be in the student's mind. The very fact of enrolling in a course implies the existence of questions. In a course in literature, the questions may run: "What special significance does the author we are studying have? In what valid ways do his world and vision differ from the worlds and vision I already know?" Of course, the teacher can give ready-made answers to some of the questions. But if he answers them before they occur to the student, he is apt to do no more than encumber his mind - or at least, his notebook - with extraneous information of no lasting value. (How I would love to teach a course in which, by mutual agreement, notebooks were banned!)

The best answers are those that the student arrives at for himself. And the best education is the one that best trains a man to find his own answers - as he must with all important questions throughout his life. Needless to say, his answers will not always be different, but they will be his own.

OBVIOUSLY, a teacher can inveigle a student into acquiring a certain amount of second-hand learning. The passing on of second-hand knowledge is easy. A parrot or a mynah can be taught to say that the galaxy nearest to our own is some 80,000 light years away. But the bird can't be made to feel any of the overwhelming awe and ineffable poetry inherent in such a fact.

Returning to our paleolithic flint tool - when it was being shaped some 200 centuries ago, the light that is reaching us tonight from the nearest galaxy to our own had already completed three-fourths of its journey toward the earth.

A mynah's mind couldn't grasp such vastness. Neither can ours or mine, at any rate. But we can understand that it lies beyond our grasp and we can feel a profound sense of mystery emanating from such understanding as we have.

This sense of mystery is a precious thing. I am not sure that mystery is essential to love, but I very much suspect that it is. Certainly mystery is one of the necessary ingredients of all the arts. For example, in a general way, we all know what poetry is. But its mystery is such that, by way of defining it, one critic has said, "Poetry begins at the very point where criticism had said everything there is to say, yet feels that everything still remains to be said.

Occasionally one runs across a teacher who seems to believe that the function of scholarship is to dispel mystery instead of enhancing our awareness and appreciation of it. (If anyone suspects that this innocent remark is intended as an underhanded jab at certain schools of literary criticism, let me hasten to assure him that he is completely right.)

"Certainly mystery is oneof the necessary ingredients of all the arts."

At the other end of the scale is the teacher who is so impervious to mystery that he confines himself to treasuring and imparting such facts as that the north tower of the Cathedral of Chartres is 388 feet high and that there are 783 figures sculptured on its south porch.

Of course teaching is beset by all sorts of other perils. Even our enthusiasm can lead us astray. How do we know what truth is? Often we don't. What we do know is that, in many cases, what we believed a few years ago we have since learned to be untrue. We write books, only to discover when we reach the last chapter, that we no longer subscribe to what we wrote in the first chapter. (Perhaps we should write faster.) Luckily, we know that any educated man is self-educated beyond any power of ours to do him much enduring harm.

The English philosopher F. H. Bradley says, "Nothing in the end is true except what is felt, and for me nothing in the end is true but what I feel." On the surface, this might seem to be akin to the most pessimistic aspects of the "forlornness" of existentialism. Fortunately, however, the man who has followed the steps through learning to understanding to love always will feel his own necessity to come to share what the best among his fellowmen, living and dead, have felt. The desire to reach beyond the limits of our own reality is a reality in itself for all of us as long as we continue to be learners and teachers.

PROFESSOR GUTHRIE'S ARTICLE, slightly revised, is based on the address, "Whosoever Increaseth Knowledge . . .which he gave at the Honors Banquet in Hopkins Center on May 28. The banquet annually honors students who have made Phi Beta Kappa or otherwise achieved distinction in academic work.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Features

-

Feature

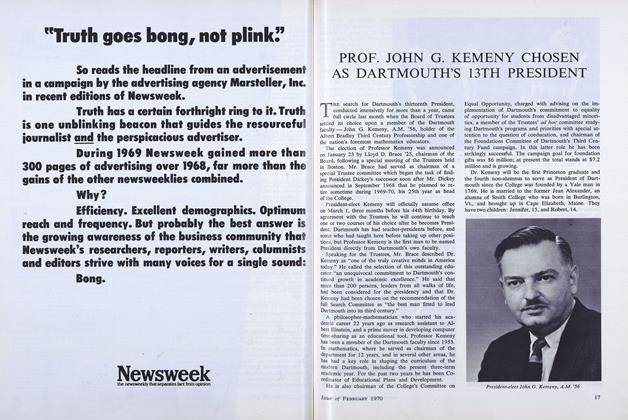

FeaturePROF. JOHN G. KEMENY CHOSEN AS DARTMOUTH'S 13TH PRESIDENT

FEBRUARY 1970 -

Feature

FeatureOpportunities for the Coming Year

NOVEMBER 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Final Report

DECEMBER 1971 -

Feature

FeatureWolf-winds at the Doorways

January 1974 -

Cover Story

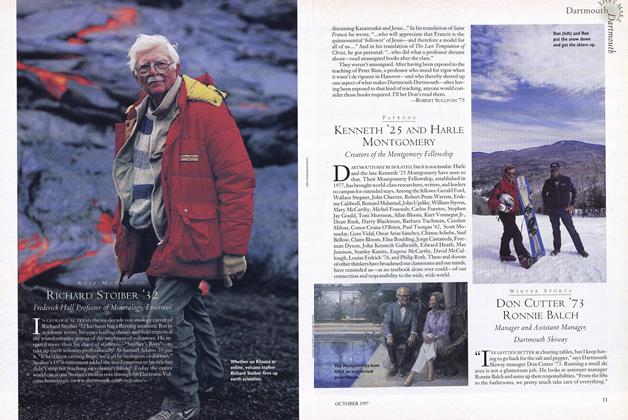

Cover StoryRichard Stoiber '32

OCTOBER 1997 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryVoices Crying (and Laughing) in the Wilderness

Sept/Oct 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91