Ten years ago Robert Averili '72 stepped up his research on Dartmouth's mountain. The rest is history. Passionate, exhaustive, obsessive history.

SPEND A LITTLE TIME in rural New England, and you're bound to stumble across a prevalent native species: the collector. Stockpiling like objects is as entrenched a New England tradition as the making of stone walls. Some people hoard strands of barbed wire; others devote themselves to less, moveable items such as wood stoves. A neighbor of mine has filled his barn with antique spades and trowels. "People start by collecting just a few spiders, and before you know it, they've got the largest collection of spiders in the known world, "says Bob Averill 72, who, possessing a well-developed case of collector's fever himself, is in a position to know.

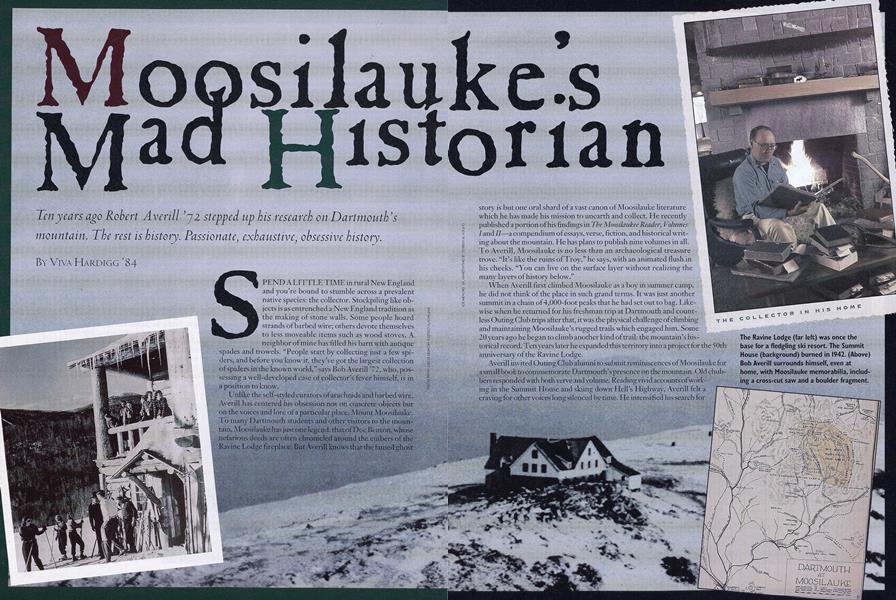

Unlike the self-styled curators of arachnids and barbed wire, Averill has centered his obsession not on concrete objects gfe on the voices and lore ot a particular place. Mount Moosilaukc. Yo many Dartmouth students and other visitors to the mountain. Moosilauke has just one legend: that of Doc Benton, whose nefarious deeds are often chronicled around the embers of the Ravine Lodge fireplace. But Averill knows that the famed ghost. story is but one oral shard of a vast canon of Moosilauke literature which he has made his mission to unearth and collect. He recently published a portion of Iris findings in The Mnosilaukee Reader, Volumes I and ll—a compendium of essays, verse, fiction, and historical writing about the mountain. He has plans to publish nine volumes in all. To Averill, Moosilauke is no less than an archaeological treasure trove. "It's like the ruins of Troy," he says, with an animated flush in his cheeks. ''You can live on the surface layer without realizing the many layers of history below."

When Averill first climbed Moosilauke as a boy in summer camp, he did not think of the place in such grand terms. It was just another summit in a chain 0f 4,000-foot peaks that he had set out to bag. Likewise when he returned for his freshman trip at Dartmouth and countless Outing Club trips after that, it was the physical challenge of climbing th and maintaining Moosilauke's rugged trails which engaged him. Some 20 years ago he began to climb another kind of trail: the mountain's his- torical record. Ten years later he expanded this territory into a project for the 50th anniversary of the Ravine Lodge.

Averill invited Outing Club alumni to submit reminiscences of Moosilauke for a small book to commemorate Dartmouth's presence on the mountain. Old chubhers responded with both verve and volume. Reading vivid accounts of working in the Summit House and skiing down Hell's Highway, Averill felt a craving for other voices long silenced by time. He intensified his search for more stories in Warren and other towns at the base of the mountain. "If you're going to be passionate about something, it might as well be interesting, and Moosilauke has an intriguing forest, lumbering, skiing, and resort history," says J ere Daniell '55, professor of history at the College. "And Bob is a man of passion. When he gets his teeth into something, he isn't going to let up." like most his collecting brethren, Averill holds a full-time job to support his passion. He maintains a dermatology practice in both Massif achusettsandNew Hampshire. Yethismedical career hasn'tstopped fffk him from tirelessly rooting about in libraries, antiquarian bookshops, historical societies, farm houses, and even overgrown graveyards or traces of Moosilauke's past. Along the way, he has discovered nonagenarians with first-hand accounts from the early days of the century. In search of out-of-print prose about the mountain, he has trolled through 300 feet of book in Dartmouth's White Mountain collection. Staff at the New Hampshire Historical Society and the state library in Concord know the red-haired doctor by name. Much of the archival material Averill has uncovered dates from the days when you could send a trunk up the carriage road and spend a month at Moosilauke's summit hotel. The mountain tended to bring out the latent poet in school teachers, preachers, naturalists, and cub reporters who wrote down impressions of their holidays above timberline.

Early on in his collecting, Averill tried to interest an academic press in his Moosilauke papers. But the editors told him the material was too local and too narrow in focus. So he founded his own small press or, in his words, his own "wicked small press," and named it "Moose Country" after the region he loves. Before tackling his Moosilaukee Reader series he taught himself the rudiments of publishing on five other books. (See sidebar, left.) This solution didn't surprise his friends. "Part of the stubborn individuality and thriftiness of Yankees is that if we find something that needs to be done, we think, why shouldn't we do this ourselves?" says Tom Burack '82, an attorney in Concord and a practiced storyteller. "People carry this to not insignificant extremes."

Averill promotes the motto of his press on bookmarks: "Skin Your Own Skunks." Roughly translated it means, "Don't pawn your dirty work off onto somebody else." Averill could never be accused of such. For example, he retyped much of the nineteenth-century material in his Moosilauke anthologies himself. He had to. Nineteenth-century typefaces don't scan well because the letters tend to be irregular and small. He couldn't trust a scanner.

Yet he sees the virtue of toiling over each page. "When you type other people's writing, it's a little like following their footsteps in the snow," he says. "You go slow, you see where they stepped, and you get a sense of what the journey was like."

He runs his wicked small press out of his house in western Massachusetts, which owes its decorating sensibilities to the Ravine Lodge. A cross-cut saw bisects an enormous stone chimney which rises to the rafters of the spacious main room. A fragment of a boulder from Moosilauke's south peak rests on the mantel. Below, a hardwood stump holds an ax at the ready. Behind a ceiling-high potted pine tree, with stacks of old journals and leather-bound books fill an office. Near Averill's computer, turn-of- the-century issues of the GraniteMonthly and Century Magazine lie alongside such titles as Bent's Bibliography of the White Mountains (1911), Vacation Tramps in NewEngland Highland (1919) and Chisolm's White Mountain Guide (1885.) With periodic help from his editor (and author of two works of historical fiction published by Moose Country Press), Jack Noon '68, Averill does most everything but the printing here, with his black lab Domino at his feet. "The publisher is also the typesetter and the graphics guy," he says.

What distinguishes Averill from many a Yankee collector is that he does not possess the hoarding impulse. He collects in order to distribute his findings in their purest form—without interpretation or even much annotation. Once he has transcribed a document or scanned in an old photograph, he gives it to the Dartmouth archives or the Warren Historical Society. "His impetus is preservation," says Noon. "Once his material is in book form and spread out everywhere, it's safe. Until then, there's a chance it might get lost."

Despite the many hours Averill has sat contemplating the subject of Moosilauke, he rarely loses touch with the mountain itself. Whether visiting the small cabin he keeps at its base or searching for lost trails, Averill still haunts the mountain with a frequency not dissimilar to Doc Benton. Dr. Averill has been known to spend many a twilight hour on Moosilauke looking for names carved in the rock and photographing them for posterity. Nineteenth-century visitors often borrowed hammers and chisels from the summit hotel to immortalize their names in stone. "As the sun goes down, a name will jump out of the rock because of the side light," he says. "It's like a lantern slide on a screen: the name's there and then it's gone again."

The magic of uncovering the secrets of this one place never dims for him. His favorite line from his Moosilaukee Reader comes from a turn-of-the century naturalist who described the call of the summit this way: "In ascending a mountain we face the path; in descending we face the world." But with a third volume to finish, and more in the works after that, Averill is still climbing toward his goal. "I'm still looking up the mountain, not at the world," he confesses. "I'm looking up the path, focusing on the top."

The Ravine Lodge (far left) was once the base for a fledgling ski resort. The Summit House (background) burned in 1942. (Above) Bob Averill surrounds himself, even at home, with Moosilauke memorabilia, including a cross-cut saw and a boulder fragment.

THE COLLECTOR

McKenney built tall tales and a place to spin them.

Charelie Smith hauls supplies to the old Smmit House, c.1935.

Moosilauke's Good Press "The Moosilaukee Reader," writes Jack Noon '68 in the foreword to the first volume, "is a companion to help celebrate Mount Moosilauke's heritage. Listen closely to the gathering of voices." Bob Averill has devoted much of the past decade to gathering voices and preserving them through his own publishing imprint, Moose Country Press. In addition to two anthologies of writings on Moosilauke, Moose Country Press has published historical memoirs, fiction, and North Country humor (the latter by the elusive author M.J. Beagle). Last spring, Averill unveiled his latest enterprise: the "official web site" of the mountain that continues to kindle his passion, . Among many things, you can order Moose Country Press books through the site. Or call 1-800-34- MOOSE (800-346-6673).

The Ravine Lodge at 60 Legendary woodcraft advisor C. Ross McKenney put the finishing touches on Dartmouth's new Moosilauke lodge in 1939. Planners predicted a useful life span for the structure, built of massive native spruce logs, of 25- 30 years. On October 1-3, the College will celebrate a much longer Ravine Lodge milestone—60 years and going strong. The weekend will include a "Ken Burns-style" documentary of the lodge's construction, hikes on the mountain, a special presen- tation to long-time dance caller Everett Blake, and the kind of big evening feed the Ravine Lodge is famous for. For details and information contact Bernie Waugh '74 at 16 Pinneo Hill Road, Hanover, NH 03755, or send e-mail to .

Room and Buckboard Provisioning at the Summit House went on ail summer except for the basics. The old Carriage Road from near Warren was still navigable by a team of horses pulling a buckboard. The road was five miles long and steep and rough for even this kind of a rig. A farmer named Charlie Smith lived just below the beginning of the road. He had a team and buckboard and he did our hauling. A full load was 500 pounds. It took the team four hours up and four hours down. We paid Smitty eight dollars a trip. A dollar an hour for Smitty, his team, and his buckboard, and a very sore rear end for Smitty after each trip. He brought fuel drums for our kerosene stoves (coal oil, he called it) and Kohler generator, building materials for maintenance work, bulk staples like flour, potatoes, powdered milk, soap, sugar, maple syrup, cases of canned goods, gallon cans of jam, peanut butter, and coffee. The rest of the provisions we back packed all during the season. Usually he was through hauling the loads by the middle of July and we wouldn't see him again on the summit until the following June. Smitty not only farmed and did our basic transport, he had also raised wildcats. At that time New Hampshire had a bounty on wildcats. One year Smitty built an enclosure out in the woods. Then he trapped wildcats until he had the right combination and let nature take its course. He gave it up after about three years because, as he puts it, "them game wardens aren't no fools." —Landon "Rocky" Rockwell '35, from The Moosilaukee Reader

Looking to Next Month Part II of a mountain's celebration: Hanover to Moosilauke in 24 Hours.

Feelance journalist ViIVA HARDIGG, the first female presidentof the D. O. C., worked on the Ravine Lodge crew in the summers of 1981 and 1982.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Research Question

October 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

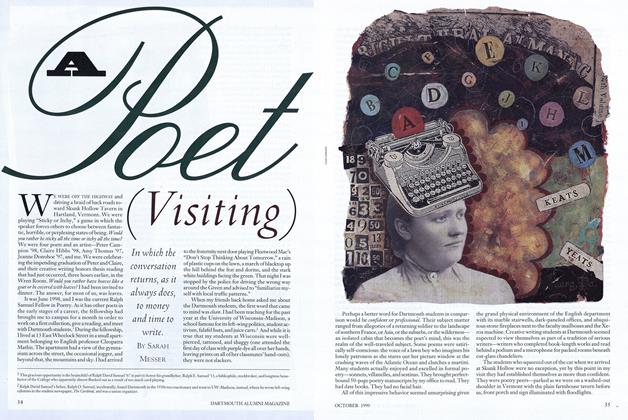

FeatureA Poet (Visiting)

October 1999 By Sarah Messer -

Article

ArticleStories on Rye

October 1999 By Tamar Schreihman '90 -

Article

ArticleTeamwork

October 1999 By President James Wright -

Article

ArticleArtists 22, Philistines 14

October 1999 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1985

October 1999 By Leslie A. Davis Dahl, John MacManus, Shelley L. Nadel

Viva Hardigg '84

Features

-

Feature

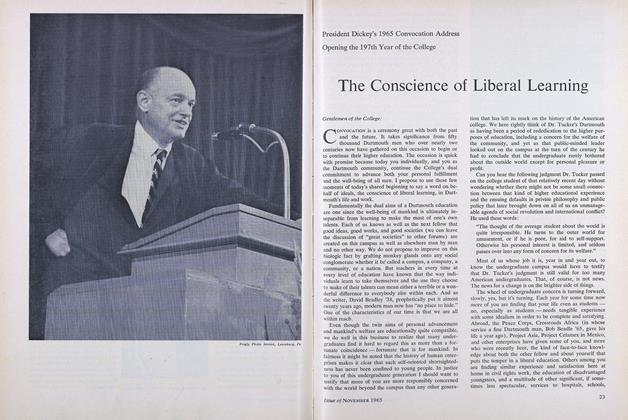

FeatureThe Conscience of Liberal Learning

NOVEMBER 1965 -

Cover Story

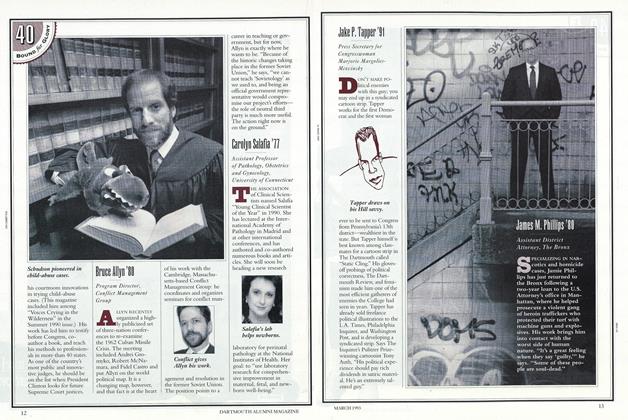

Cover StoryJake P. Tapper '91

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryMara Rudman '84

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureGod and Man at Dartmouth

March 1976 By DAN NELSON -

Cover Story

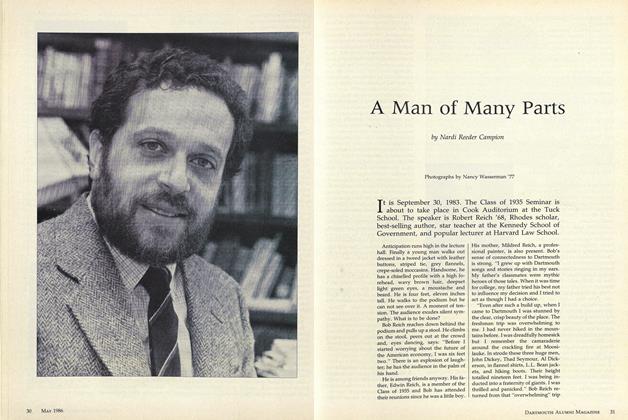

Cover StoryA Man of Many Parts

MAY 1986 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO RUMBA

Sept/Oct 2001 By ROBERT TIRRELL '45