THE COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

THE redemptive work begun by Lincoln's Proclamation of Emancipation has accomplished some significant achievements in human decency, race relations, and the march toward freedom of Negroes from chattel slavery. However, a new emancipation - to which I shortly invite your attention, is urgently needed to complete the good work it so nobly began, because the lag between initiation and fulfillment has created a dangerous vacuum.

If the present progress, which the first emancipation initiated, is measured by the status and conditions existing at the time of its proclamation, the achievements loom large on the horizon of human relations in both America and the world. But this is not the real test, for the progress attained after a hundred years should not be measured or compared with the situation of the Negro in 1863, but rather compared by and with the total progress of America and the peoples of the world since that time until the present. The progress being made by the nations of the world in terms of the tremendous movements for freedom which are sweeping Asia and Africa, makes ours look even more puny. When judged by these standards, our nation has fallen far short in many aspects of its racial progress and in some aspects, it has even retrogressed. It is indeed tragic that in this Centennial Year of the Proclamation of Emancipation, America should face its gravest racial crisis.

A hundred years to achieve the measure of racial progress we have attained is too long, too little, but fortunately not yet too late. We have little cause to rejoice over our rate of progress when nearly fifty nations became independent within a decade, and when Jomo Kenyatta, who less than a decade ago was in jail, has now become the Prime Minister of a soon-to-be independent Kenya. Nor is such little progress good enough for that nation - our nation — to whom history, time and God have given a greater responsibility for world leadership than to any other nation or people in the history of the world. Time and history will not wait for another hundred years, either for the implementation of the first emancipation or for the fulfillment of the next urgently needed emancipation. Nor will the world wait for us to assume the leadership of that freedom at home we boast so loftily about abroad.

Recent events initiated by Negro citizens have served notice in every section of our Republic that they will not wait any longer for the achievement of the fruits and the responsibilities of freedom and democracy. They want nothing more and they will settle for nothing less. Unhappily, their frustration has almost outrun their hope. But they have not yet given up methods of persuasion. The new strategy of mass sit-ins and picketing is but another but more hazardous form of persuasion because the police and the state troopers are white and white police are often more interested in preserving the old image of the Negro, and such a confrontation risks violence.

America has come face-to-face with its most dangerous domestic crisis since 1865. The racial situation in our country is far more dangerous than most citizens are ready to admit or to face. There can be no turning back on the part of the Negro; the opposition to their struggle is tougher, and will become for a while even more determined. The liberals are not yet as courageous or as free from prejudice as they thought they were; the moderates - and their number is considerable — are more frightened than ever; and waiting in the wings to take advantage of the situation, are the racists — black and white, but more white than black.

Both President Kennedy and Secretary of State Dean Rusk have sounded the alarm that we stand at the crossroads of an urgent decision for action which can lead to greater national glories or to the most devastating and widespread racial turmoil and conflict we have yet faced - one which may very well have an even more devastating effect upon our world relationships outside this country than within the nation. No section of the nation is immune from the potential danger of violence and conflict. Sectional denials of freedom and equality are not a difference of kind but of degree, and some areas of the East, North, Midwest, the Prairies, and the Far West are most vicious - though more subtly covered with the mantle of respectability and self-righteousness than much of our South. Birmingham, Jackson, and Lexington are only the strident opening bars of a prelude to what can and will happen not only in Birmingham and Jackson but in every city of this country unless we confront the problem honestly with forthright actions and with something greatly more rapid than "all deliberate speed." Today is the time for action - not tomorrow - for tomorrow is today.

IT is not an overdramatic statement that the second emancipation will, in large measure, help to determine both our national future and our survival. The present state of the American race problem mutes our voice in world politics, it stymies our leadership of the forces of freedom, it embarrasses our friends and allies, it encourages our enemies and it confuses those who have not made up their minds as to which side of the ideological struggle they will join, and it drives some of them away from us in revulsion. Indeed it affects every aspect of American foreign policy.

United Nations Ambassador Adlai Stevenson recently stated in the General Assembly that "racial incidents at home are as damaging to the United States as Communist advances abroad," and he went on to add, "this country must exert the same moral leadership at home as it does abroad if its words are to have any moral leadership and influence abroad." We never can be more abroad than we are at home.

Furthermore, discrimination, segregation, denial of full education and training and use of the Negro's talent and skills, are a great waste of the ability, energy, intelligence and manpower to the nation, this is a waste which America cannot afford because of the other perplexing problems we face at home, the serious challenges to our very survival from our enemies who have brought the threat of war and destruction to our very doorstep, and the serious problems we have with many of our allies. We need the total energies of a united people, unfettered with internal problems, the best intelligence of an enlightened and educated citizenry, each of whom, regardless of race, can place his full share of strength, wisdom, and ability at the nation's disposal and release it from the destructive ambivalence of trying to project an the world which we are unable to achieve at home. Secretary of State Dean Rusk underscored this fact when he told the delegates to the State Department conference on non-government agencies, "The successful meeting and handling of our racial dilemma is the greatest asset our foreign policy can have."

The first emancipation was an act of conscience, morality and decency, made law. The second emancipation must be an achievement of the respect and the support of the law, the moral code of religion and democracy, and the achievement of the ultimate worth and equality of opportunity and treatment of Negroes as persons of dignity, by the will, desire and action of the majority of the citizens of this land. We can legislate laws to guarantee rights and establish grievance machinery whenever rights are violated. But the law is not and never has been enough by itself alone, important as it is. The second emancipation must be an act of conscience, voluntarily on the part of individual citizens, groups, churches, labor unions, educators, politicians, and business concerns, to make the race problem their problem and the nation's problem, not just the Negroes' problem.

The almost hysterical reactions of a distinguished white judge, college president, business executive, society leader or ordinary citizen who finds that a Negro desires to move into the neighborhood, eat in a restaurant, join a club, get a job or position, attend a school or church, or ask for the right to equally sacrifice his life for the country in every branch of the armed services is just as disconcerting to Negroes and as damaging to America's honor, integrity, and prestige as Little Rock or Greenwood, Oxford or Jackson. There can be no release from the collective discriminations until individuals attain a release for the tyrant from his fears. And what Negro has not witnessed, with anger mixed with pity, the panic in even intelligent white people when they find that the last seat on the plane is beside him.

THE next emancipation will of necessity be an emancipation with a dual aspect, but its end must be freedom of Negroes from separation by whites and freedom of whites from their fears of granting to American Negroes the freedom they demand for themselves.

It must break the bonds of economic, social, political and cultural discrimination as effectively as the first one broke the bonds of involuntary servitude of Negroes, and make it possible for Negroes to develop their full capacities and pour them into this Commonwealth as an everlasting blessing to all its people.

This next emancipation must also release the white citizens by breaking the chains of hatred born of false assumptions of white superiority, the chains of fear of acceptance of the Negro as a child of God and an equal man. The genial, genderless "Uncle Tom" figure of American popular fiction is no longer - but when will the white American male accept his Negro counterpart as an individual who has long since transcended that image? The chains of the schismatic personality have developed as a result of trying to love God while despising some of God's less fortunate children, of shouting democracy to the world from Telstar and denouncing and denying it by attitude and action at home, and from the refusal to more than deplore, but to get out and lead the struggle for decency. What a force for democracy would be exerted if whites would work as dramatically as Negroes for freedom here and as courageously as they did in the case of Hungarians and Cuban refugees.

It was a naive assumption that the Proclamation of Emancipation would be a one-time act in history which would remove the darkest stain that ever blotted the fair pages of our history and set four million of God's darker children on the course to full and complete human dignity, freedom and equality within the framework of this Republic and in a reasonably short time. The sad truth, however, is that emancipation was only the beginning of a long, painful and tedious process. The enthusiasm and pride released by the Supreme Court decision of 1954 to break down the barriers to the education of Negro children led to a reduplication of the same naive assumption on the part of the people of our generation, which the people of Abraham Lincoln's time experienced, in their hope that the noble and heroic step taken would immediately be followed by a chastened, sincere and democratic citizenry, who would set to work diligently to fulfill the obligations necessary to bring the steps taken to a final conclusion within the framework of their intentions.

In the joy which overwhelmed us at a significant forward thrust in human, democratic, and racial progress, we forgot that all men are sinful, capable of both the noblest sentiments and acts of decency and at the same time also capable of violence and degradation, and that some men are mean and despicable; we forgot that guilt is a dual-edged psychological force - for it can harden the heart of the convicted as readily as it can soften it to accept redemption, and we forgot that white people, like all other people (Negroes included) have a hard. time living with other white people and often find it difficult to live with themselves. We forgot the depths of the attempt to dehumanize the Negro in this country and we also forgot that the defeated harbor deep, simmering passions of hatred against the forces and the people who caused their defeat and direct their worst venom against those of their own group who wish to be charitable, honest, fair, and ameliorative. They stew in their hatred until they are driven to brutal and irrational resistance to law and justice.

After the Emancipation Order was signed by President Lincoln, it had to be won by fire and sword - finalized by the most convulsive internal struggle perhaps any country in the world has ever passed through - sealed with the life-blood of thousands of young men, and washed with the tears of their loved ones who survived them. . .to whom fell the task of binding up the nation's wounds and carrying out the objectives of the Proclamation and helping to secure the full freedom it promised all citizens. But the hopes born with the signing of the Proclamation of Emancipation and the decision of the Supreme Court on education never came to full blossom, and almost withered on the vine. It was necessary that a long, bitter struggle - punctuated with battles every step of the way - would ensue in order that the hard-won objectives might first be preserved and defended before they could be expanded. In like manner, the begrudging tokenism, delaying tactics, refusal to heed the Supreme Court decision, interpositions, and in extreme cases, the closing of public schools as in Prince Edward County, offer an equally long, hard struggle.

FOR perhaps the first time, within very recent years, Negroes have come to full acceptance of themselves and are beginning to evolve a secure image of themselves. Thanks to the rapid emergence of Africa, most Negroes are no longer ashamed of their color or their hair, their race or their heritage. He has no apologies for who he is or what he is, for he knows he is part of America, that he helped to build it, that he died for its preservation and survival in every war the country has fought, including the Revolutionary War, and that he is entitled to its fullest blessing and protection. He will no longer beg — he is demanding his rightful share. You can nail humanity to a cross but you can't keep it there.

For decades after the first emancipation Negroes needed to be emancipated also from the fear of reprisal - from the fear of asserting themselves and standing up boldly, courageously and individually for their rights; from the fear which cowed them psychologically until today they have achieved a new pride in being, a new feeling of security and human dignity which does not depend upon the gratuities handed down in condescension by a majority of the citizenry. They have stopped saying, "I never go where I'm not wanted," and they have begun to say, "I go where I have a right to go as a respected citizen."

This emancipation has brought a new day. The old days will never return. The new and younger generation of present-day high school and college students have set themselves on a course to follow the winds of change which are blowing all over the world. These are the winds of faith-in-action which have filled the sails of the hopes of people everywhere for full and complete dignity, for equality, liberty, justice, and brotherly responsibility to help obtain and enlarge the rights of people everywhere.

One of the more hopeful signs is a large number of young white people, especially college students - North and South - who have joined them in this struggle, and for whom the very act of joining and participation often brings a breach with family, friends, associates, classmates and churches, and sometimes mortgages their future. Nevertheless, an increasing number of young white people, North and South, are standing firm and are willing also to pay their share of the purchase price for the freedom and rights of Negroes, for a better America and a finer tomorrow. Their efforts have received very little support and encouragement from their institutions and their administrations; they have done it almost alone.

One wishes that the elders of these youths - and especially their pastors, educators, parents, community and social leaders - would be as courageous, as forthright and as willing to run risks and accept penalties for the sake of fulfilling the obligations of their "Pledge of Allegiance" and the faith they profess. In terms of interest and ability to stand up for causes, without question young Americans stand first, American women are second, and American men are a very, very poor third. In their despair of youth, many elders seek refuge in the womb of indifference, fear, bigotry, and hypocrisy.

THERE is much insistence from many white people about the menace and danger of the Black Muslims. However, the nation has itself to blame to a very large degree. Black Muslims are an outgrowth of the Negro's bitterness over the limitation of his democratic rights in America. Black Muslims would have neither the reason nor the ability to exist if we adhered more completely to the ideals and principles we proclaim to be at the heart and soul of America.

The rise of Black Muslims is a result of America's failure to take the aspirations and the loyalty of Negroes seriously and its failure to understand and react as constructively to the urgency of our domestic problems as they do to our international problems.

Many Negroes, who do not accept either the Black Muslim religious tenets or strategy, praise the movement because they say it frightens white people and they thereby conclude that it serves a useful purpose. This is a highly hazardous assumption, for the first reactions to fear are usually first defensive and secondly aggressive. Fear as a method has some positive but, on the whole, very limited uses. Moreover, a frightened man or group is entirely unpredictable. Something more than fear is needed to make progress and to secure racial justice, equality and to persuade and to get people to accept progress and change. It is not fear but release from fear which is far more therapeutic.

The overwhelming majority of American Negroes are neither Muslims nor among those who believe in "separation" — another form of segregation and discrimination which Negroes equally despise. Negroes are determined to obtain their full share of the fruits of America's heritage by democratic means. They will not be misled by false prophets - nor will they be swallowed up by the hate they have fought against so long - a hatred which eventually consumes every man who indulges in it. History will be validated, in the case of Black Muslim separatism, as effectively as it was in the case of Marcus Garvey's "Back to Africa" movement in the twenties. Although most white Americans never realized it, one of the great unheralded victories over communism was won by Negroes right here in America back in the thirties when we rejected not only Communist ideology but their ideas of "Self-determination in the Black Belt" - a Communist version of the Black Muslim separation and methodology. If we are met with anything approaching our own present spirit, America's dilemma will be resolved and the whole nation and the entire world will benefit.

THE next emancipation must help to free white people from the paralyzing fear of developing normal relationships with Negroes - a fear which warps their minds, gnaws constantly at their peace of mind, and drives some of them to acts unworthy of a free, religiously motivated, democratic people. It must release them from that unfounded fear of the reprisals they believe they will suffer when Negroes gain equality or obtain equal status.

Whether anyone likes it or not, the Negroes and whites of this Republic are inexorably bound in the bundle of life as the Psalmist suggests. Neither the white segregationist, flagellate himself though he will, nor the black separationist, delude himself though he will, can ever break the bond or sever the relationship permanently. We cannot escape one another. We have arrived at the point where we have the choice of bringing our problem to a just and democratic solution soon, in order that we may face our world adversaries with our maximum strength, or of weakening ourselves from within until we are so torn that we could not hold off an insidious ideology from without. The choice is ours and the time is now.

"Shouldn't President Kennedy be doing more" and "Shouldn't he lead Negroes personally into the University of Alabama" are very popular questions. The first is valid, provided we ask the corollary question: What must we - each of us — be doing; but the second is absurd on the face of it. This is not the role of a President. Furthermore, despite any dissatisfaction some of us may have about President Kennedy, he has nevertheless taken a more forthright, open, and courageous stand on the right side of the racial question than any other President, Abraham Lincoln (though I venerate him) not excepted. But he needs and must do more. He should go directly to the people, on television and radio; he should call not one but a series of White House Conferences of governors, businessmen, educators, mayors, clergymen, and police officers, to draw them into action behind a national movement of responsible leaders. Above all, he should not allow political considerations to make a football of human rights in so far as he can help it. The suggestion of James Reston, Washington columnist of TheNew York Times, that the President travel through the South and crucial cities of the North to help mobilize citizens to assist in finding the best methods to reach the solution, is an excellent one. While the President would stir up some opposition, I for one believe he would find more support and rally and encourage more citizens to take the lead than any of us ever dreamed.

THIS is a time for bold action with strength and wisdom in which every citizen has a stake and every citizen a responsibility. Educational and religious institutions, perhaps more than others, have a great opportunity to help the nation through the crisis. To them falls most of the burden of the painful, tedious, and patient education of the mind and the conscience, of changing attitudes and of helping people to be ready for change and to accept change, of inculcating respect for persons and obedience to the law, and even the redemption of the opponents to free and equal justice for all, and the responsibility to fill the vacuum of white leadership. Up to the present, the impacts of education and religion have not amounted to as much as they ought, because the schools and the churches have not been in the forefront of the struggle and have escaped a little too easily and certainly too disgracefully, from their share of the responsibility. It is worth reiterating that our domestic crisis lays a heavy burden on every single one of us. The courts are doing their job well - although they must do more, but the basic failure of racial adjustment and improvement is at the grass roots level, in the neighborhood, the local school, shop, store, union, and restaurant. This is a time of testing both our ideals and our souls - Negro and white alike - and it is also a time for maturity and confidence.

Our destinies are one, for our destinies are America; and America, in the juncture of history where its whole future may very well depend upon the outcome of the next emancipation, desperately needs the fullest developed capacities of all its people, if it is to merit the good will, cooperation, and support of the awakened and rising masses in Africa and Asia - and of Europe and South America as well, if it is to continue to make progress and survive. But if our purpose of improvement is to impress the world, it will only be successful if we do it because it is altogether right to do so. Most nations have been defeated and destroyed not by enemies from without but by weaknesses from within - not by defeat on the battlefield but by defeat in the souls, and the loss of ideals and goals of its citizens.

Only this next emancipation of both white and Negro citizens can make for "one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all" and make it a reality instead of a noble expression of unfulfilled hope which has become a trite platitude. The future belongs only to the free.

The Chinese formed the word "crisis" by putting two characters together: "danger" and "opportunity." Although this is a time of grave danger, it is also a time of America's greatest opportunity. The graduates of the middle sixties and their children may one day, in the years to come, reflect back upon our trying time and be proud that we met the challenge of our time of crisis with courage, intelligence, and success, and left them a legacy of such complete freedom that they, from the advantage of a finer and happier day we bequeathed them, would find it difficult to improve upon.

Dr. Robinson delivering his address.

Dr. James H. Robinson, who deliveredthe Commencement Address, with President Dickey as press photos were beingtaken before the Sunday exercises.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1963 -

Feature

FeatureThe Alumni Council's 50th Year

July 1963 -

Feature

FeatureThe Past Is Prologue

July 1963 By T. DONALD CUNNINGHAM '13 -

Feature

FeatureA Record-Breaking Reunion Week

July 1963 -

Feature

FeatureThe Honesty That Is Dartmouth

July 1963 By ALAN KENNETH PALMER '63 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1963

Features

-

Cover Story

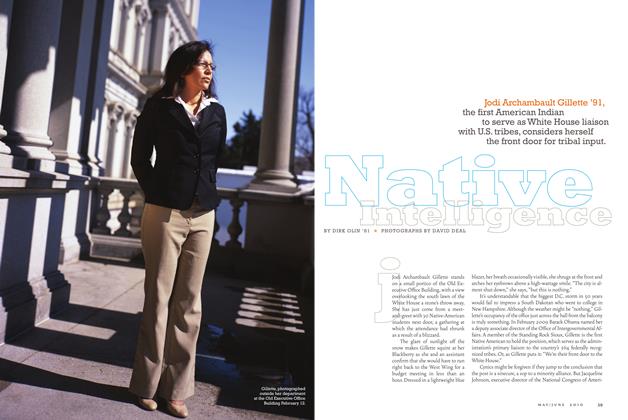

Cover StoryNative Intelligence

May/June 2010 By DIRK OLIN ’81 -

Feature

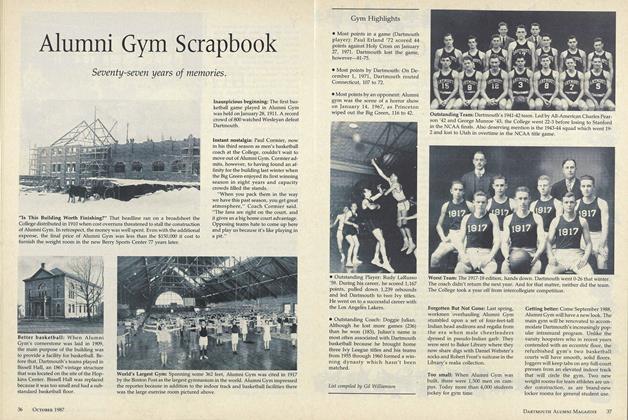

FeatureAlumni Gym Scrapbook

OCTOBER • 1987 By Gil Williamson -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Jan/Feb 2012 By Jennifer Caine ’00 -

COVER STORY

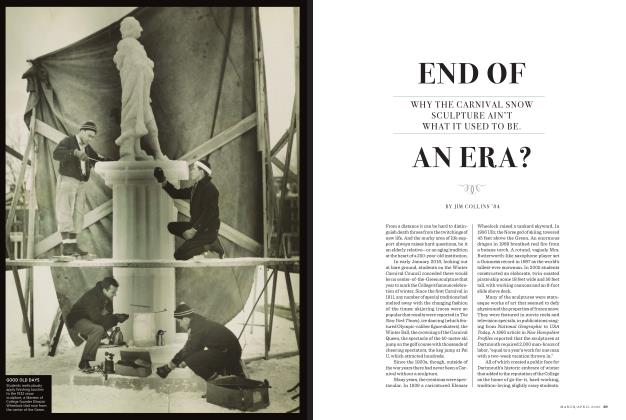

COVER STORYEnd of an Era?

MARCH | APRIL 2020 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureZen and the Art of Corporate Maintenance

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Beat of Terror

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By STUART A. REID ’08