A talk to the freshmen by Prof. Richard P. Unsworth, Dean of the Tucker Foundation

A MOMENTOUS change is going on in the ethical atmosphere in which we live. Old values and ways of thinking are under fire, and new patterns are emerging which we don't entirely understand. Most of us recognize this, but we tend to back off from the hard task of thinking deeply and creatively about these changes. We recognize that a revolution is under way, one which both intrigues us and frightens us a little.

One of the hallmarks of these days is the challenge to ethical absolutes by serious thinkers, among them a fair number of Protestant theologians. You may have had the impression before now that there are basically only two groups of people who ever bring any challenge to ethical absolutes: college students and radical, left-wing social planners; college students because they are looking for rationalizations that will make it easier to break ethical norms they have grown up with and still sleep nights, and the social planners because they are malevolently devoted to the erosion of the moral fabric of American society. That impression is nonsense, and if you have it, I predict that the odds are ten-to-one against your being able to maintain it until the end of freshman year.

Sure and reliable rules for the guidance of individual conduct and social policy seem to be disappearing like snowmen in July, not just because people look for rationalizations for their own misconduct, but because the whole way of thinking associated with absolutes and absolutism has lost our confidence.

Just to muddy the waters further, the forces that rule our family and political and financial and vocational lives are so fantastically complex that the ethically sensitive man despairs of ever being able to translate his sensitivities into any effective action....

The more complex and rationalized our institutional structures become, the more difficult and elusive some of the ethical issues become. Personal responsibility seems to get swallowed up in impersonal organizational structures, and that makes it very difficult to see where our own ethical responsibilities stop and start.

I mention the challenge to absolutism and the escalating complexity of modern life in the same breath because they are part of the same reality. The more complicated we make the structure of human relationships, the more difficult it is to find any ethical generalization that will fit all cases; and absolutism, as a way of thinking in ethics, depends on finding ethical principles that will apply to all cases they affect, and which are demonstrably a bsolute - i.e. unchanging.

Let's take a case, something simple like the Biblical commandment "Thou shalt not steal." Now you can do two things with that commandment, in order to make it work. You can say that, in certain circumstances, stealing is permissible; or you can say that, in certain circumstances, what would otherwise be called stealing is not really stealing. The one thing you cannot do is to apply the commandment willy-nilly to any and every situation.

IT is easy enough to say to a small child who is rifling his mother's pocket-book for bubblegum money that he is stealing, and that stealing is absolutely forbidden - in any circumstances. But then father, who has just preached this sermon to his child, goes to the office and tries to make a decision about price policy. He has been selling ballpoint pen points to one manufacturer for years, and has had an established price. Then comes a chance to get another half-million dollars worth of business per year if he will just sell the same product to a second manufacturer for a slightly reduced price. If he decides to cut the price for the sake of the new business, is he stealing from his older customer by putting him at a competitive disadvantage? And if he decides not to cut the price, is he stealing from the stockholders in his own company by letting the account go to one of his competitors and reducing the dividend he might otherwise pay to his stockholders?

If stealing is depriving another person of his property without his consent, when is a businessman stealing, and when is he just competing in the open market?

Or try to apply the simple maxim to another business situation. An officer of an automobile manufacturing concern buys controlling interest in a firm which supplies parts to that manufacturer. He manages to turn increasingly large orders from the auto company toward the parts company in which he has bought interest. Over a period of a few years, the stock value of the parts company increases steadily, until controlling stock is sold to another person at a very handsome profit. But all of a sudden, the auto manufacturer starts siphoning off purchase orders to other parts suppliers, and the new owner of the parts company finds himself sitting on a deflated balloon, a third or more of his orders having been given to other suppliers. And naturally, the stock value of his company drops markedly and he takes a whopping loss.

Everything was very legal. No one rifled any one else's pocketbook. And yet, a financial disaster was inflicted on the stockholders of one company by another. That example, incidentally, is not hypothetical.

Here is an ethical principle: Thou shalt not steal. And here are situations where it is almost impossible to apply the principle simply. And yet in both cases, something strongly like thievery was bound to be involved in the business decisions that were being made.

If the absolute character of ethical principles is under attack nowadays, it is no wonder. What point is there in having an absolute that can't be applied, or that can only be applied to bubblegum-sized problems?

As you become more intellectually sophisticated, you will surely come to understand how very complex the crucial ethical decisions are. As you discover that there are fewer and fewer ethical situations which are clear and unambiguous, you will also discover, first about others and later about yourselves, that very few people are able to make ethical decisions with unambiguous motives.

One of the questions that intrigues freshmen particularly is the question whether there can ever be a purely altruistic act. Does anybody ever do anything absolutely selflessly? As you would expect, it doesn't take long to come to the conclusion that most students come to, which is that no act and no decision is altogether selfless. The discovery that every ethical decision has some element of selfishness in it is a nice abstract discovery until you begin to apply it to yourself. Then comes the moment of having to reckon with the selfishness that infects your own personal decisions.

Let me recapitulate for one minute. We have spoken now about two aspects of ethical decision: one, the vanishing of ethical absolutes and, the other, the vanishing of the dream of pure selflessness. I think it is apparent that both of these are part of a larger experience which affects us at every turn in the college years, the discovery that human relationships and human responsibilities both individual and collective, are not simple and cannot be thought of in terms of pure black and white, pure right and wrong.

The process of intellectual and ethical maturity requires that you move from both the thinking and the experience that is content with simplicities to the kind of thinking and experience which is courageous enough to face up to com- plexities. So, for example, you will find' at Dartmouth that there are very few rules that govern your life in this community. I think it is the universal effort of the administration to keep rules at the minimum and-for a very clear and, if you will pardon the term, simple reason: the only ethical training for mature life that counts for anything is the training that includes the experience of being both free and responsible. You are left a tremendous amount of freedom here just because living under a spider web of petty rules and regulations is no way to develop mature ethical responsibility.

Now I want to speak for a moment about three responses to this phenomenon of vanishing absolutes and clustering complexities — three responses which you will see being made in one way or another by fellow students. These three responses are all of them useless and fruitless. The only reason I bother to mention them is to help you identify &em and, hopefully, avoid them. I will call these three responses by three labels. The labels don't mean much except to give you a tag. Let's call them paralysis,cynicism, and privatism.

The response of paralysis is the response of the man who, realizing that significant ethical decisions are exceedingly complex, finds himself unable to come down on one side or the other. The most obvious example is what you will see on November 3 when some people will respond to the present political campaign by staying away from the polls. Some of these will be people who have come to feel that neither candidate is someone they can support wholeheartedly and because they can't make any decision that satisfies them as being right, they will end by making no decision.

You are likely to see ethical paralysis in the college community either in yourself or in someone else at those points where a man waits too long to make an ethical commitment — so long that his commitment is irrelevant by the time he gets around to making it. Last year, as you will probably hear, there were a couple of cases of straightforward racial discrimination on the part of fraternities at the time of rushing. There were a fair number of men who had a clear idea of the ethics of this sort of thing and a clear feeling that something ought to be done about it. But values come in conflict with each other. In this case, respect for the feelings of some of the brothers, even though one couldn't agree with them, and respect for the dignity of the persons discriminated against were two values that were in conflict. The result was that most of the people who had ethical convictions about the disease of discrimination ended by doing nothing.

If situations requiring decision are complex, it is a ghastly mistake to respond to that fact by doing nothing because you are not sure you can do the absolutely right thing.

A second useless response to the vanishing absolutes is cynicism. What I mean by cynicism is basically mistrust of anything that seems to be decent or noble. It is one thing to be hardheaded, realistic, and to avoid being taken in by high-sounding phrases and appeals to naivete and idealism, but it is quite another thing to despise either other men or yourselves because you know something about the worst side of the human animal.

One of the remarkable things to me about the Civil Rights movement is the way its best leaders have been able to achieve a hardheaded realism without ever becoming cynics. They have understood, for example, that in many towns and cities nothing will be gained for the Negro citizens by repeated appeals to human decency and kindness. They know that the rights which are being withheld will not be extended until the price for withholding them is higher than the price for extending them. So they will use tactics of economic boycott or public embarrassment or civil disobedience until the seat on which the white power structure sits becomes too hot to be comfortable. They are quite realistic about how legislation gets passed and how it gets enforced, and yet I have rarely met one of these leaders who despises the men he is working against.

One of the great temptations of the cynic is to substitute analysis for commitment and to discount the social commitments of others on the grounds that you know their motives aren't pure. The mechanism is pretty transparent. Many is the time I have heard students trumpeting like a victorious elephant because they have caught a do-gooder with his ambitions showing. This is a sleazy way of saying, "If his motives aren't pure, then his deed isn't really good; and if his deed isn't good, then there is no reason why I have to ask myself why I'm not doing the deed myself."

Politicians are always faced with this sort of criticism, the sort which exempts the critic from responsibility because he has found a flaw in the other fellow's moral armor. You may find the same thing happening here with the cynic who refuses to take his share of responsibility in campus life because he thinks he has the "number" of those who do take leadership.

This is not to say that the careful examination of motives isn't important. It is. It is one of the products and one of the purposes of the reflective life. But you'll have gained some maturity when you spend your efforts first on developing honesty about your own motives, and learn to make your judgments more cautiously on other people's motives. And you will have achieved more maturity when you learn to have rather more concern for what a man finally does than for the way he feels about it. In our psychologizing age, this is hard to do. But it can be managed.

The third reaction to vanishing absolutes I termed privatism. This is a reaction that is more characteristic of the present decade than of any period I can remember.

Privatism is a concentration on one-to-one personal relationships and the individual man's decision about his personal affairs as the only realms of ethical significance.

In part, privatism is a healthy reaction against some facets of an increasingly impersonal world. So much has been written about the organization man and the lock-step conformity of our social habits that a pendulum-swing of reaction has set in. The more we rationalize social relationships, the more we try to reduce group life to patterns that can be fed into a data-processing machine, the more we try to lock the human spirit into an iron grip of predictability, the more the human spirit rebels and tries to kick over the traces.

The more we look at tyrannical societies notably Fascist and Communist societies - the more we see a depressing kind of social conformity that we want to avoid for ourselves at all costs. That impulse is not unhealthy. And to the extent that privatism as a state of mind in ethics is a reaction against iron-clad social conformity, it is not an unhealthy reaction.

Privatism is unhealthy when it reacts to the threat of social conformity by retreating from social responsibility. It may be understandable that people find less and less meaning in group relationships and retreat to the intimate relationships in search of something meaningful, but it is not a healthy thing.

WE used to say that there were two main topics of conversation in college dormitories, and that religion and football tied for second place. Sex has always been the front-runner, of course. And the debates about the status of sexual morality have gone on from time immemorial. In that respect your college generation is no different from any other. The difference that does exist, however, is that we have seen in very recent years an increasing preoccupation with sex beyond what you would always expect in people at your stage in life.

The preoccupation, it seems to me, is a reflection of this phenomenon of privatism. The idea is very deeply embedded in our minds that society is pretty hopeless, and the last outpost of human dignity is the individual. One individual in relationship to one other individual, therefore, is the last outpost of social experience that has any authenticity and any honesty about it. I think myself that it is pointless to pass a lot of moralistic judgments on the present preoccupation with sex, as if it were evidence of the pure licentiousness and perversity of the younger generation. There are people who will regard it that way, of course, but they miss the point, because they don't seem to understand that it is part of a search for salvation by people who have become disillusioned with the transcendent relationships of religion and with the social relationships of any groups larger than the intimate family. Of course, if you eliminate both God and society as sources of discovering the meaning of human existence, it should be no surprise to see people trying to find that meaning in the intimate relationship of sex.

It is interesting to me that the age which talks most about its sexual liberation is the age which is more slavishly obsessed by sex than any other, in recent history at least. Insofar as the actual liberation of sexual attitudes means that we become more matter-of-fact about this aspect of the human experience, it is a good thing. We have tended to make either a demon or a god out of sex, neither of which helps us to see and understand its human significance. Whatever helps restore this human perspective is to our advantage. But insofar as the liberation of our attitudes about sex means that we divorce sexual conduct from responsibility and sensitivity to the honor and dignity of persons - others and ourselves - it is a perilous liberation.

Preoccupation with sex and the justification of sexual license are things to which you will have ample exposure at Dartmouth, of course. Incidentally, if people try to tell you that Dartmouth is worse than most colleges on this score, I would be skeptical. If they try to tell you that it is more virtuous, however, I would be absolutely incredulous. Quite seriously, this is not a problem of a college, but a problem of a whole society. You will have to come to terms with it, of course, and you will have to make some fundamental decisions about your responsibility as a man. Some of you are bound to decide that your responsibility is strictly to yourself, and that you are free to take whatever privileges you can in this regard. Others will make elaborate rationalizations for the fact that privatist escape from responsibility is really noble and virtuous - and who knows, they may even believe themselves. Then there will be others, and I suspect a good many others, who will recognize that personal integrity and social responsibility have something to do with each other, and will plot their course from there.

Privatism has other forms, equally fruitless, the best laboratory examples of which can be found in the very suburban communities from which the largest number of you have come. The emphasis on consumption of goods, on ownership of the maximum number of gadgets, on living up to and beyond one's income, even when it requires a little imagination to decide what one can spend his money for next; the celebration of the "good life" in terms of ease, leisure, and the absence of challenge, and the failure to face up to the realities of poverty and human squalor in our society; all these are indications of the ascendancy of a privatist ethic. Privatism is the ethic of the gloriously self-contented, whose contentment is the good they most want to seek and to serve. Its inadequacy to the most important problems that face us is too obvious to need explaining.

I THINK it is clear enough that absolutism as a way of ethical thinking has lost its status nowadays, lost it both philosophically and practically. I don't propose that we start a crusade to put the vanishing absolutes back on the throne. I mistrust crusades and I would especially mistrust any crusade whose aim was to "advance to the rear" and embrace a concept of ethics which we have shed for the good reason that it was not a sufficiently large-minded way of thinking to be relevant to the complex and perplexing ethical situations which face us.

Still, the responses I have spoken about here - ethical paralysis, cynicism, and privatism - are patently sick reactions, in their separate ways. The problem becomes that of suggesting better responses to this fact about ethics. That is a difficult problem because of the pluralistic kind of society we live in. I am a Christian, sub-species Protestant. Some of you are Protestants, but Protestantism is such a sprawling, variegated movement that that doesn't create very much theological unity among us. Others here are Christians of the Roman Catholic sort. There are Jews among us, and a few representatives of Eastern religions. And, there are a whole lot of you who would call yourselves agnostics, perhaps even atheists. The melange of religious beliefs we represent is one of the things that has brought about the collapse of absolutism in ethics. We no longer have a common set of ultimate convictions on which to base the penultimate ethical convictions. Actually, we never had much religious unity in the United States, but the Protestants used to think we did. Now that we have grown up some as a culture, the Protestants are beginning- just beginning — to be aware that it is a little unreasonable to expect a Jew or a Roman Catholic or an agnostic to live up to the old Protestant virtues.

In spite of our religious disunity, however, we have a shared understanding of some characteristics of human dignity and decency which can provide us with a better response to our vanishing absolutism than the ethically futile responses I have described. If we can't have in common an ethic of absolutes, we still share an ethic of service. An ethic of service can give the kind of shape and purpose to your educational experience that it must have if you are going to leave here with anything more than a degree and some nostalgic memories.

Each of you will have to fill in the details of this ethic in terms of your own vocation, your own talents, your own relationships. But there are three things I want to suggest to you as characterizing this alternative to ethical absolutism.

One is sensitivity, in particular a sensitivity to the difficulties other men have to cope with. A man cannot seriously want to give himself to the service of other human beings and be flippant or callous or judgmental about the other fellow's trials. There isn't a one of you who doesn't bear some kind of cross, who doesn't have something that eats at him, makes him uncertain about himself, makes his sense of value and sense of purpose come unstrung from time to time. And how rarely most of us are aware - or even try to be aware - of the cross that another man carries, however quietly and secretly. An ethic of service is in the first place built on a developed sensitivity to the needs of others. This doesn't come naturally to anyone; what comes naturally is not to give a damn about anyone's problems but one's own. That kind of sensitivity has to be built consciously and carefully and in defiance of all the things in college life that feed our collective and individual egotism. But it can be done, and it is the first ingredient in an ethic of service.

The second is responsibility. In a way, I hate to use the word, because it has been so denuded of meaning; but I don't know a better one. What I mean by the word is two-fold. In the first place, it is the willingness, once having seen what the cross is that another man bears, to shoulder it with him. Not instead of him - that would rob him of his responsibility; and not in spite of him - for that would rob him of his freedom; but with him. Only secondly do I mean by responsibility what usually comes to mind first: i.e. accountability, the business of being answerable for what you do. You will find, of course, that the college administration will stand ready to help you develop your ethics in this sphere more than in most. It is a traditional college sport to play a kind of cat-and-mouse game with the deans by seeing how close you can run to the edge of the rules without getting burned.

But when I speak of responsibility, I mean something profoundly more serious than keeping the rules. Rules are only necessary and minimum boundaries, designed to keep an element of decency, honor and order in the community. The deeper ethical significance of responsibility is the knowledge that you are accountable whether anyone is looking or not, whether anyone is putting up requirements or not.

The sum total of human misery in this world is very great. The kind of responsibility I am talking about is the acknowledgment that you and I share an accountability for the existence of that misery as well as for its alleviation. An ethic of service doesn't go on the theory that all acts of charity are magnanimous exceptions to the normal rule of selfishness. It goes instead on the theory that, when we pick up some part of the load of human need, we are simply fulfilling a responsibility that is properly ours.

The final thing that characterizes this ethic of service is a sense of usefulness. George Bernard Shaw is credited with saying that it is far better to end up as a clinker, burned out and thrown on the ash-heap, than to wind up as a little grey clod of grievances and petty concerns. It is better to wind up on the ash-heap, if in the process of being burned out you have given some light and a little warmth to humanity.

You have a tremendous opportunity, while you are here, to discover the way you can be most useful to the world - whether in art or science, business or one of the professions - and to get a running start on the long process of equipping yourself to be useful. The one thing I hope is that you will not be content just to decide what kind of a job you want, but will push hard to discover your vocation, your calling, the particular way that you can be useful in this world.

There is an ethical upheaval going on in our society. Old absolutes are vanishing, and will not be conjured back into existence. As far as our ethical structures are concerned, we can't go home again. But we dare not be homeless, either. An ethic of service, which stresses sensitivity, responsibility, and usefulness, is the only thing I can see as a viable and fruitful alternative in this world of hard demands and complex choices in which you and I now have to live.

The Rev. Richard P. Unsworth with students in the Tucker Foundation office.

"There is an ethical upheaval going on in our society. Old absolutesare vanishing, and will not be conjured back into existence.... Anethic of service, which stresses sensitivity, responsibility and usefulness, is the only thing I can see as a viable and fruitful alternative inthis world of hard demands and complex choices."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Battle To Reform The Education of Teachers

December 1964 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40 -

Feature

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

December 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

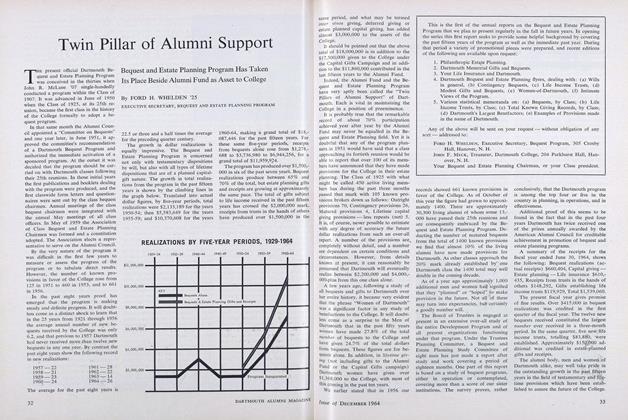

FeatureTwin Pillar of Alumni Support

December 1964 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

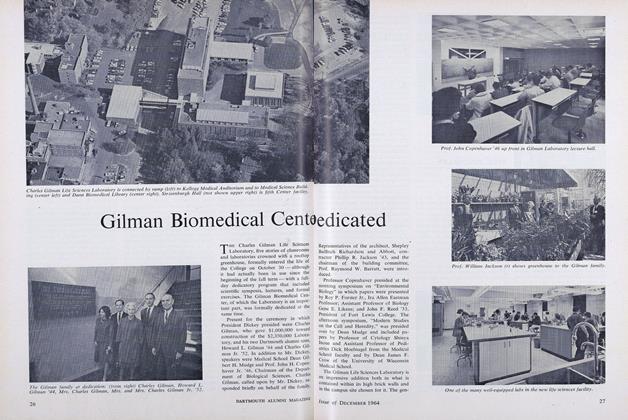

FeatureGilman Biomedical Centedicated

December 1964 -

Article

ArticleNine John Ledyards, Modern Style

December 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1964

Features

-

Feature

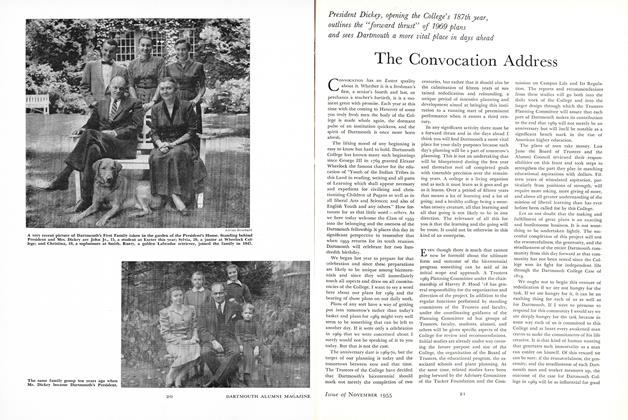

FeatureThe Convocation Address

November 1955 -

Feature

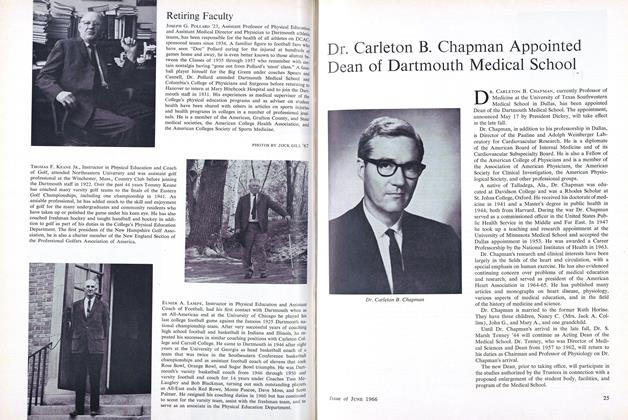

FeatureDr. Carleton B. Chapman Appointed Dean of Dartmouth Medical School

JUNE 1966 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Disease

SEPTEMBER 1983 By George O'Connell -

Feature

FeatureManin the Red Flannel shirt

January 1974 By M.B.R. -

Feature

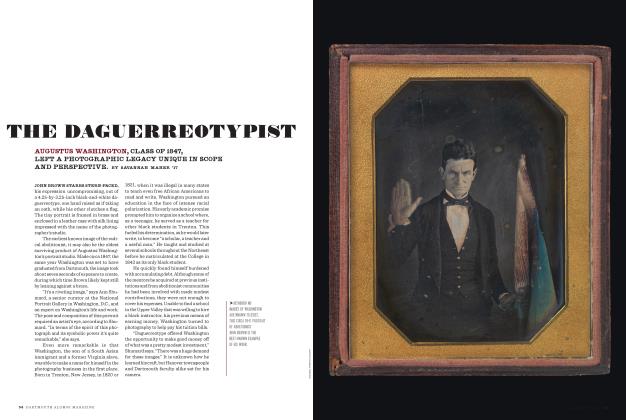

FeatureThe Book That Was Banned in Hanover

JANUARY 1999 By Robert H. Nutt '49 -

Feature

FeatureThe Daguerreotypist

MAY | JUNE 2017 By SAVANNAH MAHER ’17