Dartmouth Canoeists Get"Education of a Lifetime"in Their Danube Trip

BECAUSE they "hadn't gone 1600 miles to stop three miles short" of their goal, nine Dartmouth canoeists had to seek the cover of darkness in order to slip their craft once more into the waters of the Danube River for the dramatic conclusion of a summer-long adventure.

The first rays of the sun on the morning of September 7 blazed from the surface of the Danube estuary, and flashed in reflection from nine paddles which dipped and rose from the swells of the Black Sea. It didn't matter then that small boats were forbidden to wander that far out; nine weary but elated veterans of the Connecticut had come a long way from Ledyard Bridge.

Nine months of intensive planning, detailed in part in the February ALUMNI MAGAZINE, had raised more than $16,000 in cash and equipment, and had carried the message of their coming into many parts of Eastern Europe. Passports, visas, shots, and trans-Atlantic passage — the usual concerns of most European tourists, had been only incidental to this undertaking. Given the chance to penetrate the Iron Curtain in their favorite style, by canoe, they were determined to develop every meaningful contact with the peoples of those nations, and to capture in picture and word as much as possible of the experience. From National Geographic they received a full complement of the finest photographic equipment available, in exchange for first rights to the story, which should appear in the magazine this spring. Polaroid, Old Town canoes, and Abercrombie & Fitch joined the Society as major public underwriters of the expedition; 54 separate sources finally contributed.

And so the trip in its execution was as natural and beautiful as the idea of it had been from the beginning. The men would see the Danube swell from the trickle of a spring in tiny Donaueschigen, in southern Germany, into an 80-mile-wide delta on the border between Rumania and the Soviet Union. After four days in Ulm, Germany, where they first put their boats into the water, they could number among their friends at least 75 members of the local Kanuclub who gave them a riotous farewell party, complete with banners, drinking games, and exchanges of songs. It was probably just Dartmouth's pride which rallied the nine to get off at the appointed time when a fond crowd had gathered to bid them auf wiedersehn, but the cold fast water quickly brought them around. Stopping for lunch one of the first days out they were told by an astonished shepherd that "they would need a lot of time and God to get as far as the Black Sea."

In Regensburg the trippers drank the famous Bavarian beer with students from the teachers' college, and traded "As the Backs Go Tearing By" for "Schwabische, Bayerische." When they fell behind schedule, reporters with whom they had lunched phoned ahead to hold monstrous locks open for them. Arriving in Passau on the Austrian border after 12 hours of paddling, they were greeted by the mayor on the city dock and invited to dinner of gypsy steak and cognac at the City Hall.

Austria before Vienna was the breathtaking beauty of the region known as the Wachau, steeply terraced vineyards, and the castle of Schreckenwald (Terror in the Woods) who ruled the Danube in the 11th century. Stretching a chain across the river to exact a toll from passing ships, he would offer uncooperative captives the choice of jumping from the ramparts or starving to death on a ledge. The group thoroughly explored many of these noble ruins, with Chris Knight '65 and Dick Durrance '65, the chief photographers, scrambling over the cliffs for better views of the postcard scenery.

A "farewell to the West" celebration capped four days in Vienna as the men faced the crucial transition to the world behind the Iron Curtain. An Austrian police boat escorted them to the border, and the last sounds they heard as they approached the Czech river patrol were the strains of "Hello Dolly" blaring out over the water, and the Austrian officials ceremoniously wishing them a good journey.

Despite the imposing concrete-and-barbed-wire barriers marking the line, the entry into Czechoslovakia was no more difficult than other European border crossings; on this trip the Iron Curtain would gradually become more and more, of an "imaginary line" as the expedition formed real ties in the eastern countries. "Putting faces on abstractions," Chris called it. From Bratislava, their first stop, the Tatran Boat Club had sent two canoes upstream to escort them to a dockside welcome by some 60 people. A memorable evening was passed in the home of the club director, where they ate cheese and drank sheep's milk, slivovitz (plum brandy), and home-made wine. On the way home their host suggested a stop in a local pub, where they had their first encounter with borovitchka, the distilled pine sap that on this occasion showed potential as a real "force" in East-West relations.

Five Czech students, two boys and three girls, who traveled with them after Bratislava, encouraged them to abandon their canoes for a swim when the sun was high. Soon fourteen bodies and seven boats could be seen drifting down the tide, a soccer ball flipping from one to another. They visited a collective farm and bought a pair of ducks for dinner on sudden impulse: the warmth and gaiety of the meal they shared that last evening together could not be spoiled by the toughness of the birds.

This then was the pattern of the trip, more or less. Politics were completely submerged in what became more of a happy pilgrimage than a diplomatic tour. A "Ledyard Canoe Club 1964" pin, presented to a Hungarian border official, overcame visa regulations, not only to let them into the country a day early, but also to mark the occasion with indelible impressions on both sides. The group had traveling companions in each country, to help them out with unfamiliar languages and to share the fellowship of the great river. They found local people looking for them after hearing about the trip on the Voice of America, if they hadn't also seen them on national television or in the newspapers. Mike added: "That doesn't mean that we didn't really shock hell out of a few sleepy Yugoslav and Rumanian villages, nine guys trooping ashore in bright orange rain parkas."

"We found official attitudes a lot friendlier than we had ever hoped for," they recounted. "Sure we ran into snags, like when Durrance was grabbed by armed guards while shooting a construction site in Belgrade. But then how could he have known that the building going up was Tito's new national defense headquarters?

"When people gave us trouble, the fault was usually just a personal attitude, like the tendency to be impressed with one's own uniform, which is really pretty universal. And when they went out of their way to help us, it had nothing to do with the rules; they were just being helpful."

Proud of their independence from Moscow, the Yugoslavs knew one word of English - "liberal" - and the Bulgarian student guide went out of his way to point out that though Communism was right for his country, he wasn't interested in imposing it on anyone else. In the cities the visitors saw Communist achievements, handsome though cheaply built housing developments. But Russian exploitation of satellite Rumania "made Western imperialism look puny."

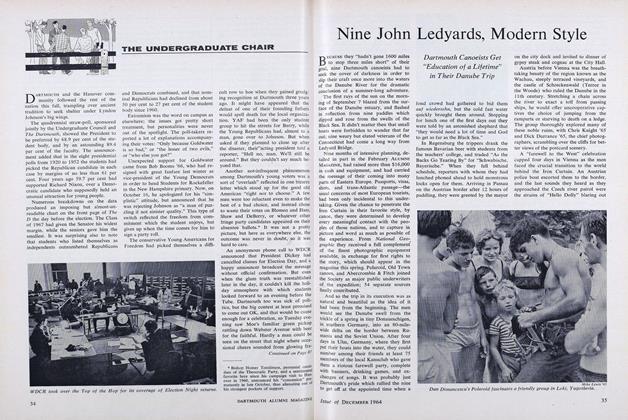

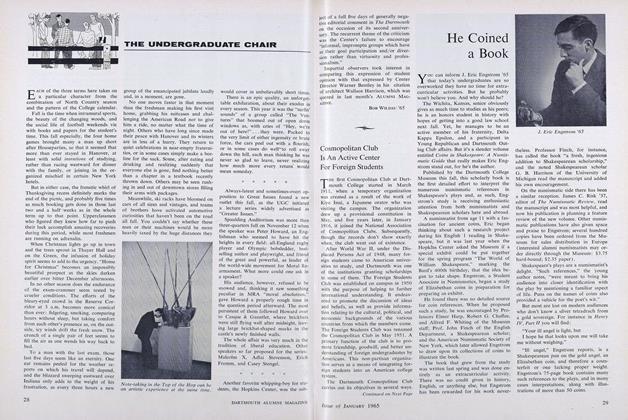

These then were their discoveries. But the constant stream of visitors to their campsites were much more interested in their camping gear and cameras than in their "political baggage." Never having handled such fine materials, they wanted to touch everything: tent canvas sleeping bag fillers, and heavy rainwear. " 'American technique!' they would exclaim," Chris recalled. "And we would get all kinds of big offers for our nylon parkas; they'd never even seen nylon in many places." It's not difficult to understand how Dan Dimancescu's Polaroid pictures were met "with sighs, smiles of disbelief, friends, and often food." And their full-color views of Dartmouth were first looked on as a propaganda trick.

"We encountered none of the usual questions about why the U.S. wants war, but we were floored at the way that little kids could point at an issue of Life and say 'McNamara' or 'Humphrey.' How many of us would have known Brezhnev or Kosygin before last month? For Goldwater we found an almost universal fear, if not hatred, and for John Kennedy the deepest love; his name came up constantly. They still think that a righ-twing plot killed him.

"We never had to preach, or try to hide things, because they knew too much already. Their papers leave out a lot, but they lean pretty hard on the racial issue. Just being there was enough; they'd ask questions and we'd answer. The people we met are just drops in the bucket in relation to the total population of these countries, but we know that they gained new and different impressions of the U.S., and for us of course it was the education of a. lifetime."

Perhaps the best measure of the trip's success is that if they had it to do over again, they say there is very little they would change. They have brought most of it back in some 18,000 slides, in addition to Polaroid pictures and movies, and thousands of words of notes and commentary. A slide showing in Spaulding Auditorium in October drew an outstanding crowd, and trequests for weekend and vacation appearances continue to pour in.

Curiously enough, the canoes are still in Rumania as the expedition fights what may become the thorniest diplomatic problem of all. Rumtrans, the state-Swned shipping company, wants more than the boats are worth to ship them home, and for the moment refuses to let them out any other way. But when they are returned, enough money will remain to set up a small fund for future ventures of this type. The men are seeking a way of bringing counterparts from Eastern European nations to the U.S. for a similar voyage down one of our great river systems, but for the moment prospects look dim of getting such travelers out of their home countries.

In the meanwhile, the memory of the Danube Expedition of 1964 will remain an inspiration to those dreamers of big dreams, future generations of Dartmouth men in whom John Ledyard's wandering spirit still stirs.

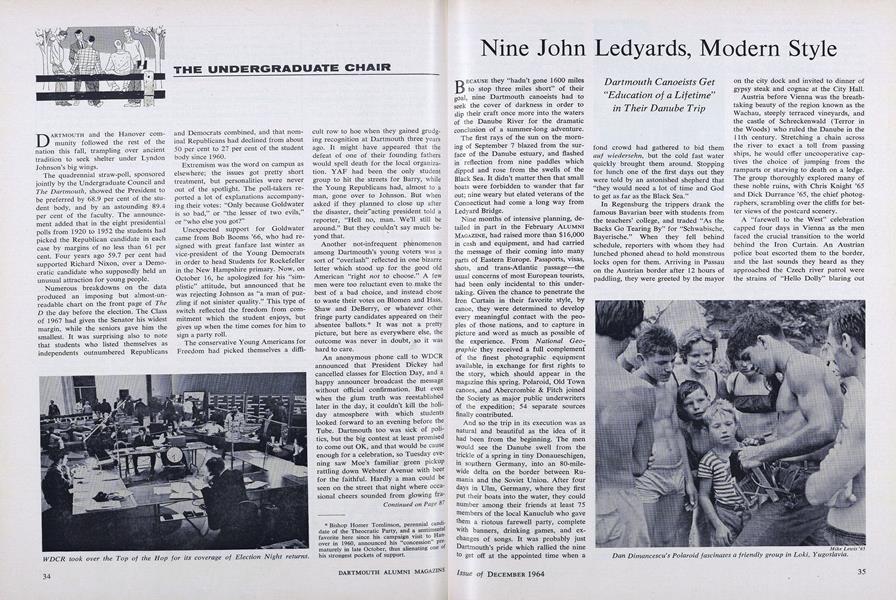

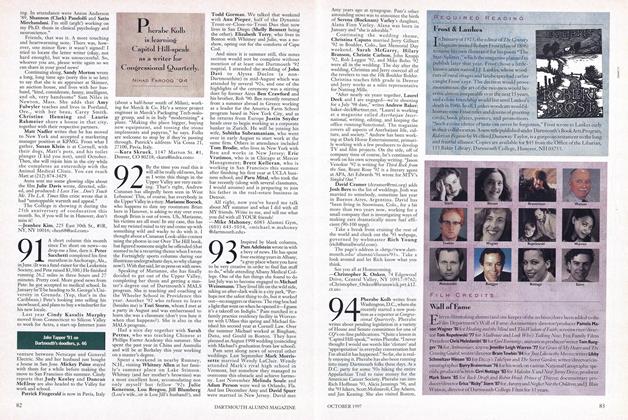

Dan Dimancescu's Polaroid fascinates a friendly group in Loki, Yugoslavia.

A shepherd and fellow Yugoslavs in Lokiinspect camera and camp equipment asdid natives everywhere the canoeists went.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureVANISHING ABSOLUTES

December 1964 -

Feature

FeatureOur Battle To Reform The Education of Teachers

December 1964 By THOMAS W. BRADEN '40 -

Feature

FeaturePRESIDENT'S POLLSTER

December 1964 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

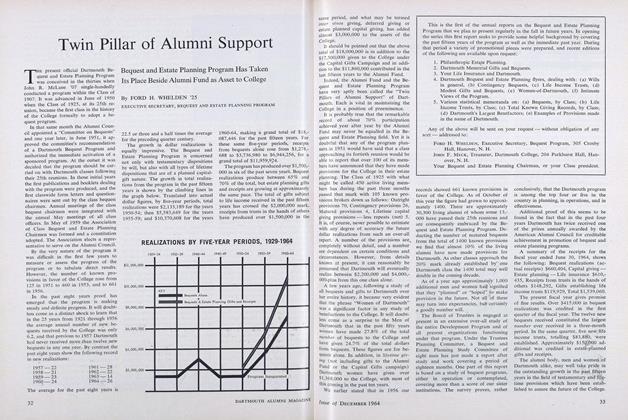

FeatureTwin Pillar of Alumni Support

December 1964 By FORD H. WHELDEN '25 -

Feature

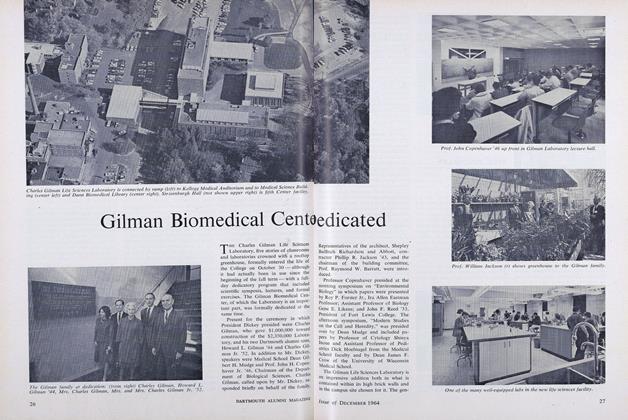

FeatureGilman Biomedical Centedicated

December 1964 -

Article

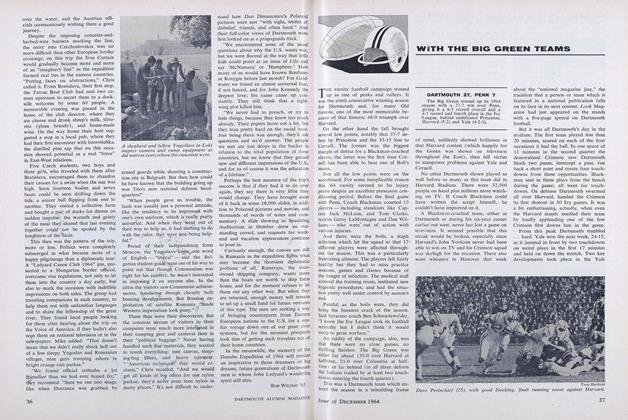

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1964

BOB WILDAU '65

-

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

NOVEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

DECEMBER 1964 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JANUARY 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MARCH 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

MAY 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65 -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

JUNE 1965 By BOB WILDAU '65

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE STARTS REMODELING INTERIOR OF HALLGARTEN HALL

June 1921 -

Article

ArticleThe Way It's Done

APRIL 1982 -

Article

ArticleFrost & Lankes

OCTOBER 1997 -

Article

ArticleHockey

JANUARY 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleFish and Game in the Outing Club

April 1937 By HENRY M. DOREMUS 37 -

Article

ArticleWith the D. O. C.

December 1938 By J. W. Brown '37.