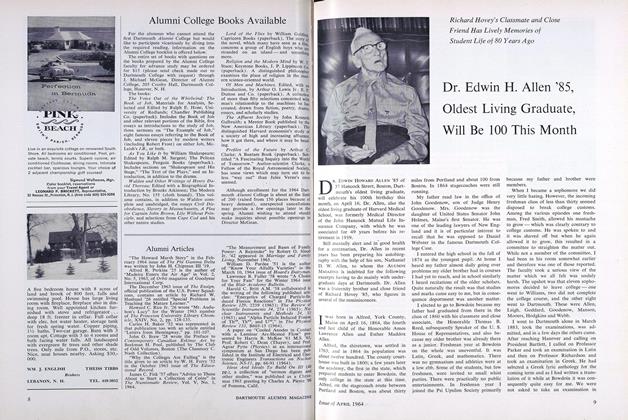

THAT increasingly indispensable "thinking machine" - the high- speed electronic computer - will soon be available to practically every Dartmouth student and faculty member who needs to use one, and knows how.

According to plans for a new Computation Center announced by the College in late February, all one will need to do is to step to one of the sixteen input-output stations strategically located about campus and transmit his problem by teletype to the medium-range GE 35 computer now being installed at a central campus location. A problem with a few thousand steps will be answered in a matter of seconds; one with a billion steps will require several hours.

Two Dartmouth mathematicians who directed the planning of the center Professor John Kemeny and Associate Professor Thomas E. Kurtz - say that its users may well be getting the fastest service on research of any institution in this country.

The fast service will be possible because the computer will allow virtually simultaneous use by several questioners from their own departments through a time-sharing system. The computer will consider each problem in turn for at most a few seconds. While the questioner is thinking about what to do next, the computer is considering, in turn, all the other problems new and old that it is dealing with.

It will in effect "wait in line" for the user, help search out the "bugs" in programing, and even remember the questioner's place if the call is interrupted.

According to General Electric technicians who helped plan the installation, this is probably the first time that such a large percentage of a college's students will have effective, almost simultaneous access to a computer. It will be almost as though each had a high-speed computer of his own to work with.

The cost of the installation is estimated at $800,000. The National Science Foundation recently made a $300,000 grant to the College and to Professor Kurtz, director of the center, for equipment and installation. At the same time the NSF gave Professor Kemeny $84,150 for the first year of a two-year program involving experimental undergraduate instruction in computing.

In the experiment, computer concepts will be included in the introductory mathematics curriculum, from the most elementary courses on. Since about 75 per cent of all Dartmouth undergraduates now take at least two mathematics courses, a high percentage of all students will learn something of computer capabilities, and those majoring in the sciences and engineering will receive more intensive instruction in techniques.

Professor Kemeny estimates that at least two-thirds of the undergraduates will find it necessary to use the computer in years ahead. "And certainly all students will find a need to understand the relationship between man and computing machine and to assure that in this relationship man is the master."

According to Prof. Leonard M. Rieser '44, newly appointed Dean of the Faculty for Arts and Sciences, tens of thousands of trained programers will be required to use high-speed computers in coming years, but perhaps more important, millions of persons will be directly affected in their daily living. Thus, Dartmouth believes that it has an obligation to include experience in computing and data processing as part of liberal education.

PROFESSORS Kemeny and Kurtz point out that the major bottleneck in using a computer is "machine time." Yet frequently the computer itself is standing idly by waiting for the problem to be presented through the input devices. Another difficulty is "debugging." This is technical jargon for testing and correcting the complex program that must be written for the machine.

Thus, while the actual computations might require only fractions of a second, a potential user might have to wait hours to present his problem because those users ahead of him were "inputting" their problems. As a result he may have to spend days or perhaps weeks getting access to the machine and "debugging" his problem.

The key to the Computation Center's time-saving is the General Electric Datanet 30 machine which acts as a monitor of incoming programs and the sixteen remote "input" machines. It sorts out the problems and files them on a disc memory which is capable of storing several million numbers or instructions and can have them available in a fraction of a second. The central computer can take up these problems one at a time for servicing at the monitoring machine's command.

Thus, instead of students and faculty members waiting in line for access to the machine while one program is processed, they simply call the Datanet 30 from their respective departments and type out the program. They can then continue their regular work and await the results in their offices. If the program needs "debugging," the machine will call this to their attention. The central computer will then go about working on the other problems while the user seeks out the "bug."

Even here the corrections are no more difficult than simply erasing a line once the mistake is found. The user simply summons back from the disc memory that part of the problem that is in error, erases it and substitutes a new instruction, without presenting the entire problem again.

Professors Kemeny and Kurtz estimate that 90 per cent of the problems presented will be what they define as "small"; that is, involving only a few thousand steps and mere seconds of computer time. Nine per cent will be "medium," involving a few million steps and perhaps minutes of computer time. And only one per cent will involve a billion or more steps or several hours of computer time.

In addition to the Computation Center now being installed, Dartmouth has two digital computers - an LGP 30 and an IBM 1620. Dartmouth faculty members with highly complex problems also have access to the New England Computing Center located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

April 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureOldest Living Graduate, Will Be 100 This Month

April 1964 By Dr. Edwin H. Allen '85 -

Feature

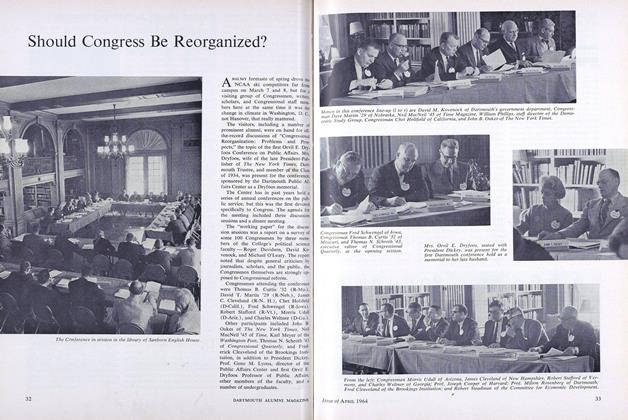

FeatureShould Congress Be Reorganized?

April 1964 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926

April 1964 By KENNETH W. WEEKS, HERMAN J. TREFETHEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1924

April 1964 By CHAUNCEY N. ALLEN, PHILLIPS M. VAN HUYCK -

Class Notes

Class Notes1920

April 1964 By CHARLES F. MCGOUGHRAN, JOHN S. MAYER

Features

-

Feature

FeatureEleven Professors to Retire

June 1960 -

Feature

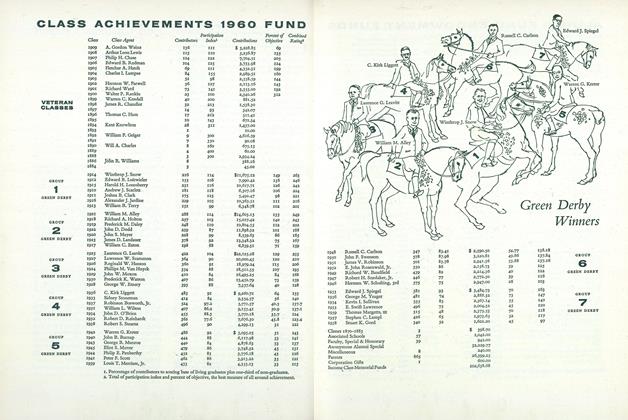

FeatureCLASS ACHIEVEMENTS 1960 FUND

December 1960 -

Cover Story

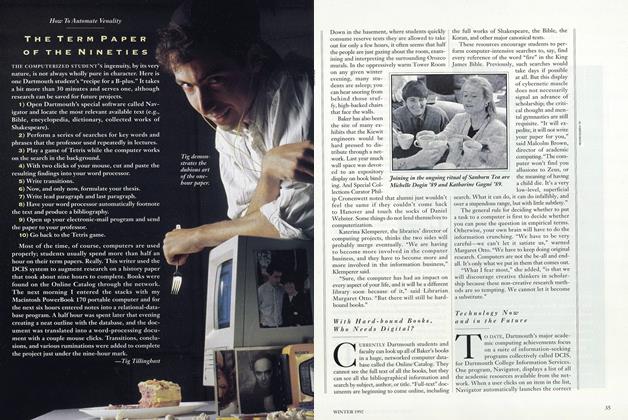

Cover StoryWith Hard-bound Books, Who Needs Digital?

December 1992 -

Feature

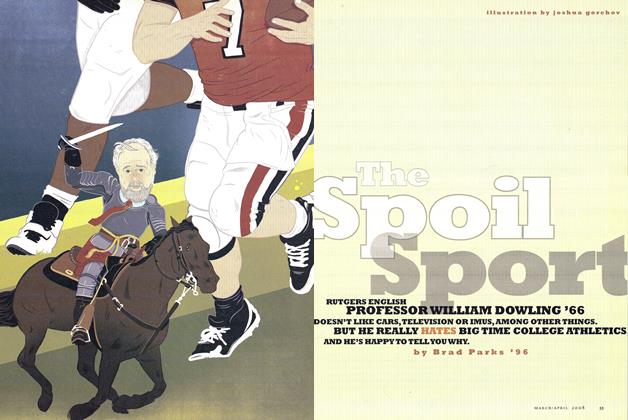

FeatureThe Spoil Sport

Mar/Apr 2008 By Brad Parks '96 -

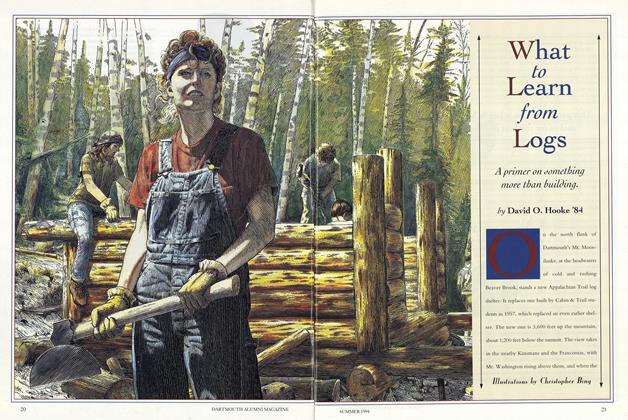

Cover Story

Cover StoryWhat To Learn From Logs

June 1994 By David O. Hooke '84 -

Feature

FeatureBad Things You Learned in Gym

OCTOBER • 1987 By Lee Michaelides