THE COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

PRIME MINISTER OF QUEBEC

SEVERAL years ago, whenever I traveled outside Quebec, people whom I had occasion to meet used to ask me, amongst other things - just as they probably asked anyone else who came from my province - whether Canada's French-speaking population was very numerous, and whether this population, grouped particularly in Quebec, could hope to survive much longer in the Anglo-Saxon world of North America. In short, by asking these questions, people really wanted to know about Quebec.

Today, they know the answer, statistically at least; but people are continuing, perhaps more than ever before, to wonder about Quebec. People are now asking themselves — and are also asking us - just what is going on there. As a matter of fact, they have learned through news media that Quebec, which used to be so calm and so seldom a source of sensational news, is now going through the most dynamic period of its history.

The cause of this curiosity varies with each individual. Some are particularly struck by appearances; to them, the usual calm has given place to a period of upheaval, the proof of which they see in the sensational character of the news that they hear or read. I will simply say that the interpretation of facts from a distance is more difficult because the events that are reported are generally the ones that are most likely to strike people's imagination. This is just as true for Quebec as it is for all the other parts of the world.

Others believe, with some nostalgia, that the Quebec which they felt was some kind of a North American window on the past is about to lose its attraction as an old pastoral and historic monument and to succumb to modernization under the influence of new and dangerous apostles of a selfish materialism. However, this view of the facts is just as false as the other I just mentioned. Even more false is the interpretation of the facts according to which Quebec, by disassociating itself from the rest of North America, is on its way to becoming a territorial "en-clave" where ideas and undertakings foreign to the dominant liberalism of this continent could flourish.

And finally, there are still others who believe that Quebec is getting ready to declare itself a country distinct from Canada and the United States, having had the temerity to choose to accept all the responsibilities and to run all the risks inherent in absolute sovereignty.

As a matter of fact, the truth about Quebec is far more complex than this. Today, as Prime Minister of this interesting and, for some people, disturbing province I would like to take advantage of this opportunity that you have kindly given me to show you, as briefly as possible, the meaning of the change that is taking place in Quebec. This will not be the first time that I have done this outside Quebec, but as events are developing with unprecedented rapidity at home, I like to get back to this subject every now and then.

I HAVE often said that what has taken place in our province is the phenomenon of a people finding itself. In fact, the Quebecers of today - and this is perhaps what distinguishes them most of all from the Quebecers of yesteryear - not only know from whence they come, but they also know what they can become. Their attention is directed less towards the past, and their efforts are. directed more towards preparing for their future. They have shifted their sights and havetaken their destiny into their own hands.

The Quebecers of today believe essentially that it is within themselves and through themselves that they will find the solutions to their own problems; they do not expect these solutions to come from somewhere else. Above all, they know that from now on, by maintaining a firm attitude and by a sustained effort, they will be able to succeed in the positive endeavors that they undertake. They have lost the feeling of insecurity which can be found down through their history. They feel that it is now possible for them to achieve the things they have been dreaming about for two centuries.

Where exactly does this new awareness come from? This question would require a very long answer, and I prefer to leave it to the historians to study at their leisure. For the moment, I will satisfy myself by saying that Quebec, because of its own development and the gradual increase of its level of education, and also because of the example given to it by certain less well-endowed countries that are faced with even more serious problems has understood its own abilities, and has, as it were, measured its own strength. It has undertaken to use these abilities and this strength as efficiently as possible, in order to reach the objectives it has set for itself by its decision to take the place that it believes it should have both in Canada and in the modern world.

Would you tell me that all this is ambitious? Perhaps; but when I look back upon the road that we have traveled in Quebec during the past four years, I believe that in spite of everything, our initial ambition was tinged with a great deal of realism. I hasten to add that the government which I lead is not alone responsible for all the progress that is shaping the face of a new Quebec.

Nevertheless, in order to facilitate and support this progress, the government played its part by setting up institutions that were lacking in the economic, educational, social welfare and administrative fields. And if the government of Quebec had to play this part, if it had to extend its field of action into areas which are almost always exclusive to private enterprise in North America, it was because the people of Quebec proved that they were being realistic and could adapt to a changing world.

LET me explain. Anyone who knows something about the situation of a cultural minority also knows the situation of the French-Canadian group in our country. As a matter of fact, a minority does not always have the tools it needs to achieve its legitimate aspirations. If it had, it would not be a real minority, because its relative influence in the country's affairs would be greater than its demographic proportion. In Canada the only important institution over which the French-Canadian minority exercises any real control is the government of Quebec. It was normal, therefore, for us to use this government as a lever for collective self-assertion and as a means of action, be it only through a desire for efficiency and speed.

While the results obtained so far have not exceeded our hopes, they do show, however, that we did proceed in the right way, and that we must continue on this course of action.

What did we do? We wanted to play a greater part in the conduct of our country's affairs. We insisted upon respect for our rights. We undertook to have a larger place within Canadian Confederation. We wanted to put into practice the theoretical equality which was granted to our ethnic group under our country's Constitution.

The things we did, logically, to reach such an objective, and the firmness we showed, radically changed the equilibrium that had heretofore existed in Canada. By reforming several of our institutions, by solidifying amongst ourselves the new dynamism that was moving us, we have also disturbed the existing order in Quebec itself. And all things being equal, a similar phenomenon appeared throughout the whole country when it was realized that the attitude we would have from now on was not one of these surface movements we had known so often in the past, but that it came from a new total desire to assert ourselves as a people. The usual techniques of appeasement or diversion were discarded in advance because we had risen almost unanimously against a fundamental defect in the Canadian political system. Only a major correction of this fundamental defect would succeed in satisfying our present aspirations.

This basic flaw is the difficulty in which Quebec finds itself, of not being able to develop in its own manner in those spheres which either come under or should come under its own jurisdiction. In several of these spheres, as a matter of fact, we are at present subject to federal authority which, while it theoretically re- spects the autonomy granted to us under our Constitution, seriously limits in practice this autonomy.

AT this point, I must emphasize two A things. First of all, as far as Quebec is concerned, the federal government's role will be radically altered by the changes that will take place in Canada, not only in the field of taxation but also in the control that exists at present in sectors where joint action by both the federal and Quebec governments is being carried out. Some people look upon this as a threat to Canadian Confederation. There is certainly a threat to federalism as it is being lived now, because this is the federalism we intend to reform. But between this and saying that the existence of Canada itself is in danger, there is a leap that only fanciful minds can make. Because Quebec is at present seeking freedom of action which would be in keeping with the aspirations of its people, it does not follow that this freedom can only be gained at the expense of Confederation. I personally believe that our political system is flexible enough to allow country to reach the normal objectives of any adult people by itself and in its own way.

The second thing that I would like to emphasize is the underlying reason which is guiding our actions. The French-Canadians, the majority of whom live in Quebec as you know, form a well-established and very articulate cultural community in Canada, a community that is proud of its language and its particular characteristics.

Cet héritage, nous voulons absolument le conserver sans nous dérober aux devoirs du dépositaire, devoirs qui nous lient même envers les Franco-américains de la Nouvelle-Angleterre. Il est des attaches d'autant plus impossibles à rompre qu'elles sont impondérables, affinités electives qui, sans infirmer la loyauté à des pays différents, denotent cependant une fraternité indestructible qui a joute son ciment à l'amitié de deux grands pays voisins.

Furthermore, we also know that boundaries have a tendency to disappear in the modern world. At first sight, what we are doing may seem contrary to this development of a more general character. To people looking at us from the outside, we might appear to be turning inwards upon ourselves, while everywhere else in the world distance no longer exists and cultures are intermingling. But this is only an apparent contradiction. If we want to assert ourselves further, we cannot sit on the sidelines and merely watch the tide of modern history. On the contrary, we shall want to play our part in the history of our times; but we feel that if we do not assert ourselves now, if we do not provide ourselves with the tools that we are still lacking, we, as a minority, will be easily submerged by material cultures more powerful than ours, starting with American culture itself; in this way, we would lose all our influence.

In other words, the moment one acknowledges human and civilizing values in a given culture - and all cultures have these values - then we are left with no choice: we must preserve them and allow them to develop. This is what we have decided to do in Quebec at the economic, social, and political levels. We consider that this is our duty. If we do not do these things, we will be repudiating precisely what makes us different from the groups that surround us. It is necessary for us to stand on our own feet; it is imperative that we do so, for it is not only our country but the whole of North America as well that could benefit from the contribution of the French Canadians to North American civilization.

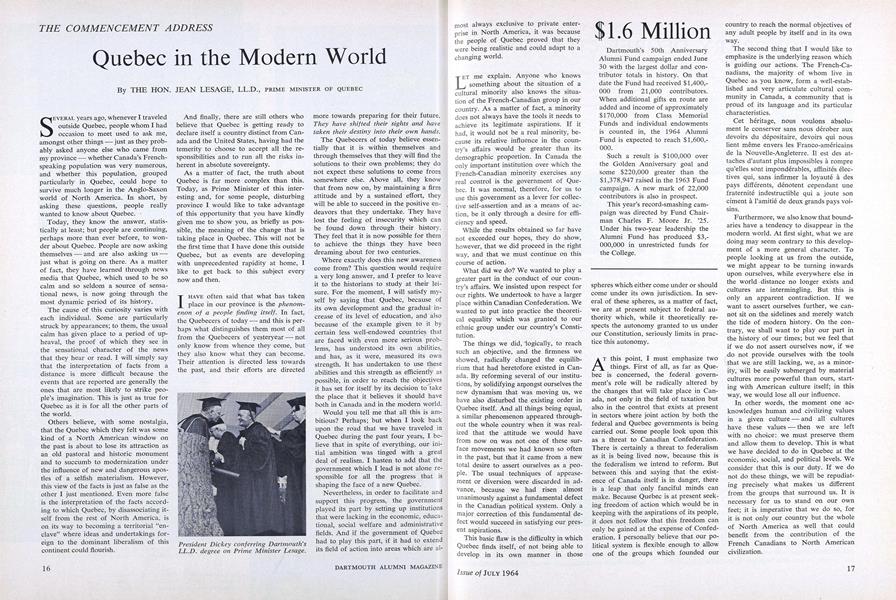

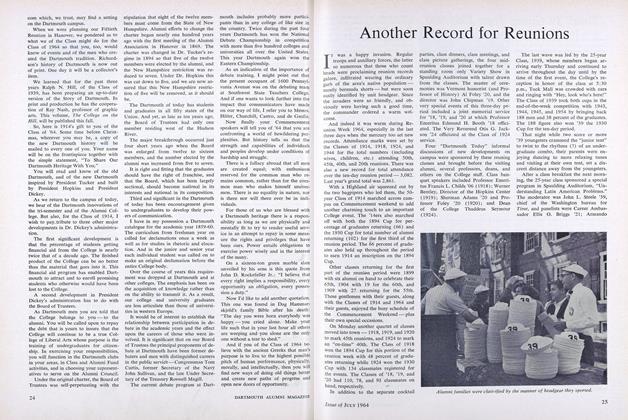

President Dickey conferring Dartmouth'sLL.D. degree on Prime Minister Lesage.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Heritage and An Obligation

July 1964 By SIGURD S. LARMON '14 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1964 -

Feature

FeatureLandauer Heads Alumni Council

July 1964 -

Feature

FeatureA Look Backward and A Look Ahead

July 1964 By MICHAEL JAY LANDAY '64 -

Feature

FeatureAnother Record for Reunions

July 1964 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1964

Features

-

Cover Story

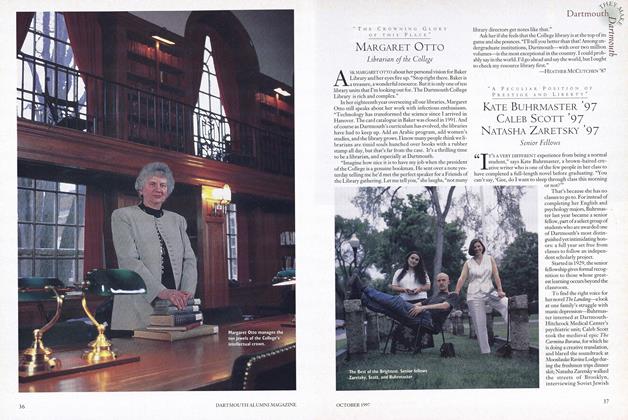

Cover StoryMargaret Otto

OCTOBER 1997 By Heather McCutchen '87 -

Feature

FeatureEleazar Wheelock and the Dartmouth College Charter

DECEMBER 1969 By JERE R. DANIELL II '55 -

Feature

FeatureDennis Brutus Speaks Out

SEPTEMBER 1984 By Kendal Price '78 -

Feature

FeatureForged by Flame

Nov/Dec 2005 By LEE MICHAELIDES -

Feature

FeatureA Murmur of Normalcy

Jan/Feb 2002 By NELSON BRYANT '46 -

Feature

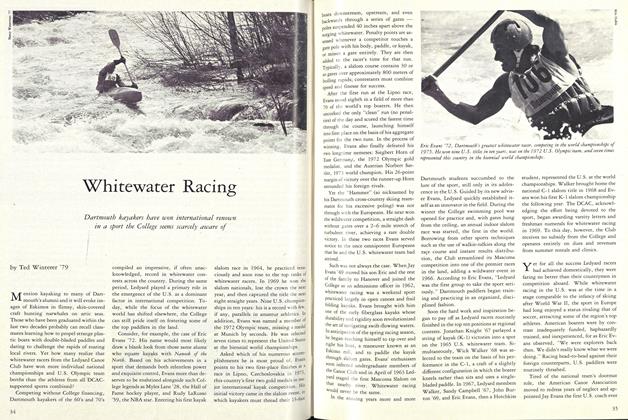

FeatureWhitewater Racing

APRIL 1983 By Ted Winterer '79