DURING a recent conversation about the teaching of ethics at Dartmouth, an administrator at the College recounted an incident that occurred his freshman year, sometime in the late fifties: All freshmen were then required to participate in a course called "The Individual and the College," designed to orient the newcomers to the mores of the academic community the requirement of academic honesty, for example. One of the assignments was for individuals to keep a journal chronicling their reactions to the obligations of college life. According to this College official, who clainjis that "writers of detective stories handle all the great moral issues much more straightforwardly than anyone else," the course was deathly dull and poorly attended. When it came time for the journals to be submitted, the instructors found that the few journals that had been faithfully kept had also been thoroughly copied. For whatever reason, the course was discontinued. Nowadays, whatever the status of the Honor Principle, the teaching of ethics is on firmer ground, actively engaged in providing students with the intellectual tools for thinking rationally, and practically, about moral issues.

Although the driving purpose of the Reverend Wheelock's college was the education of young men for careers in the clergy, it has been more than a century since faculty meetings opened with prayer and longer still since the curriculum was tipped toward theology. Nonetheless, long after making the transition from a religious to a secular institution, Dartmouth has persisted in proclaiming its purpose as having something to do with moral education.

President Hopkins was fond of talking about the College's duty to produce men of "moral fiber"; in speeches about the nature of the liberal arts college he frequently cited its "primary concern" as "not with what men shall do but with what men shall be." President Dickey once wrote that "today's college cannot commit itself in these matters to much more — or to much less — than the conviction that good and evil exist, that it is an educated man's duty to know and choose the good, and that it is part of Dartmouth's work to prepare men to make that choice." The latest formulation of institutional purpose, promulgated by President Kemeny and the Board of Trustees in 1976, holds that Dartmouth's business is "the education of men and women who have a high potential for making a significant positive impact on society."

The conflation of moral concerns and education, however uneven and sometimes inconsistent, permeates the whole life of the College its structure, organization, and policy. The Tucker Foundation's activities; reasons given for decisions about the Indian symbol, coeducation, and hiring practices; standing committees on equal opportunity, affirmative action, and investor responsibility; the Honor Principle; and a growing number of courses dealing explicitly or implicitly with moral issues and reasoning are a few examples of what Warner Traynham '57, dean of the Tucker Foundation, referred to recently as Dartmouth's "hopeless" entanglement in ethics.

"No value-free communication between people is possible," Traynham claimed, "and my stance is that having a valueneutral institution is neither possible nor desirable." Not only is it impossible to talk about the human community without dealing with ethical questions, he argued, but even the study of the most inanimate of the sciences is bound up in morality, if only as a practical concern for how research is to be conducted. He also maintained that the faculty has an obligation, either in or outside the classroom, to involve students in a consideration of the moral questions posed by the potential uses of knowledge. "Preaching versus teaching is not an ironclad separation, and I wouldn't want it to be. If there is some value transmission going on in a teaching situation, it's better to have it overt instead of covert so the people involved know it's there."

MOST of the overt consideration of ethics, but precious little preaching, goes on in the Religion and Philosophy departments. Ronald M. Green, associate professor of religion, teaches a demanding introductory course in "Religion and Ethics" that focuses on the relationship between moral reasoning and religious belief, a class in "Comparative Religious Ethics" that explores the relationship more thoroughly, a popular "Sexuality, Society, and Religion" course, and a seminar on "Decisive Cases in Religious Ethics." In addition, he and his wife, Mary Jane Green, assistant professor of French and Italian, teach a comparative literature course, "The Ethics of Existentialism," which examines the question of whether or not moral responsibility can be developed independently of religious belief. "At heart," Green said not long ago, "I'm a student of comparative religions who thinks ethics is central to religion." He is planning a long-term research project, begun in his book Religious Reason, of documenting ethics as the common terrain between widely divergent religious traditions.

Students have commented that they find Green's classes particularly challenging, that they appreciate the intellectual discipline he brings to a discussion of topics to which they have seldom given rigorous or systematic consideration. Green observed that most of his creative philosophical work takes place in preparing for class. "I have an internal demand to present material clearly, and I'm very unhappy if that doesn't work. At the same time, most of my good ideas come out of moments of weakness in the classroom. If an argument isn't intelligible, there's something wrong with it." Teaching people to think critically is one of the ways he sees his role in teaching about ethics. "Ethics is not a simple matter of sharing opinions. Like law, it is a matter of vigorous argument. Some views can't be adequately defended. There are better and worse ways of making moral decisions. The first requirement is intellectual honesty and openness."

When Professor Bernard Gert, present chairman of the Philosophy Department, came to Dartmouth some 20 years ago, the only ethics course the College offered was the equivalent of the "Introduction to Moral Philosophy: Plato to Mill," now taught by Professor Robert J. Fogelin. The department's curriculum has expanded to include "Philosophy of Medicine," taught by Gert and Professor of Psychiatry Charles Culver, and "Ethical Theory."

The theory course is based largely on Gert's book The Moral Rules, which presents a rational, non-traditional defense of traditional morality. The rules Gert puts forward and defends are familiar; not surprisingly, there are ten of them: "Don't kill, don't cause pain, don't disable, don't deprive of freedom or opportunity, don't deprive of pleasure, don't deceive, keep your promise, don't cheat, obey the law, and do your duty."

Gert wants "to make a difference," he says in the introduction to his book, "not only in one's understanding of morality, but also in the way one acts. ... I wish to increase as much as possible the influenc of moral considerations, not only in the life of each reader, but also in the life of our entire society." His job as a philosopher and teacher "is to introduce clarity" into thinking and the use of language, Gert said. "I try to get students to free themselves from 'word-magic.' Most people don't think about what they are doing and saying. For the most part, on most controversial issues, most people don't want to think clearly. As a moral philosopher, I don't have any special access to the facts, but if I can eliminate the problem of confusion, I've come a long way."

Green and Gert were asked about the relationship between religious ethics and moral philosophy. Religion, Gert claimed, is primarily related to the culture of different societies. Although he recognizes religion's force as a motivator for ethical action, he's wary of the failure to distinguish between religious requirements and ethical requirements the tendency to make religion, instead of reason, the determinant of what is moral. "Putting religion above ethics sounds good coming from Kierkegaard," he pointed out, "not so good coming from the Inquisition."

According to Green, the study of religious ethics is interested, much more than philosophy, in what religions teach about ethical issues, the ways beliefs bear on moral choices, and how those beliefs affect people. "For most of the major ethical questions," he argued, "it is what religions think that has a profound influence on our thinking. Religious ethics brings depths of insight or confusion that philosophy neglects. It brings a larger self-understanding of human nature and destiny. What is lost is some of the technical focus that the philosopher has. But the same critical skills are required for both, and the two approaches are complementary.

"Gert thinks there is all the difference in the world between his moral theory and mine; I think there is very little," Green acknowledged. "It's a debate we're constantly engaged in. For the person outside moral philosophy, our positions are almost indistinguishable. We are both 'natural law' moral philosophers. We're objectivists, not relativists. We look toward an impartial reasoning process for making moral choices. The difference is in our account of rationality. Gert does much of his creative work in that area of difference, so he tends to emphasize it. But it makes little practical difference."

BOTH professors see the growing number of Dartmouth courses dealing with ethical concerns as a reflection of a general interest growing in our society. That interest has been prompted, they suggested, by technological advances presenting new moral problems, the increasing responsibility for making moral choices that the professions have had to assume, the vacuum left by the decline in the influence of traditional religious ethical systems, publicity given to events such as Watergate and the Karen Quinlan case, and increased interest by philosophers in practical and applied ethics. At Dartmouth, in addition to religion and philosophy classes, classes in biology, comparative literature, economics, and education all state in their course descriptions the intention to delve into questions about right and wrong. So do classes in environmental and policy studies; women's, Native American, and African and Afro-American studies; government and anthropology not to mention the professional schools. The intensity and sophistication with which ethics is treated varies, but there seems to be a growing consensus about the importance of making the effort.

Professor Roger Masters teaches an upper-level government course, "Biology, Medicine, and Politics," that deals explicitly with medical ethics and the practical moral questions advanced by developing biomedical technology. The course also looks at more theoretical issues, Masters noted, such as whether or not there is a "natural basis" for ethics. In another course, "Modern Political Thought," ethics is considered implicitly through the study of political theories advanced by Hegel, Hobbes, and Rousseau, who found it necessary to combine an analysis of how people actually behave in society with a description of how they ought to behave.

The moral issues within the study of political science are "a bottomless pit," Masters observed. They are at the center of concerns for the relationships of people in communities and at the root of questions about the power of government. "It's legitimate for the professor to explain a certain view of how things ought to be," Masters said, "but there shouldn't be any preaching. One has to be very aware of the potential for the abuse of a professor's power. There are unethical ways of teaching ethics. I shouldn't compel someone to accept my judgments. I shouldn't dictate ethical responses."

Frank Smallwood '51, a government professor and chairman of the Policy Studies Program, teaches "Ethical Issues in the Policy Process," a case-oriented course in decision-making required of policy majors, that presumes previous study in ethical theory. "First we try to agree on a definition of what a fact is, which can be .surprisingly difficult, and then we look at a variety of actual cases in terms of the relevant facts, assumptions, and values," Smallwood explained. Outside experts are brought in to present differing points of view about the issues under consideration, and students are required to make reports advocating policy decisions. Last term, students had a series of informational meetings with Tuck School Professor John W. Hennessey Jr., who serves as chairman of the Educational Testing Service. They then prepared advisory reports on issues in testing and education many of them ethical issues pertinent to the testing service's search for a new president.

"There is a lot of built-in frustration in teaching this kind of a course," Smallwood admitted. "When you lecture, you're in control of the situation, but with this kind of open-ended questioning there is a lot of slippage. At first, before things took off, students kept wanting answers. They kept asking where we were going. Part of the purpose is to gain an appreciation of how all of us bring our own biases to the issues. We can't kid ourselves in thinking we are totally objective. We're not trying to teach what is right or wrong but an appreciation of the nature of decision-making. You have to be a good listener."

"GENETICS and Society" is taught this year by Paul Sullivan and J. C. Schultz, visiting assistant biology professors. The course attempts to give non-science majors a thorough understanding of genetics as a basis . for exploring some of the social and moral problems presented by advances in the science and its associated technology. "It would be great if the biology majors would take a course like this," Sullivan said. Moral issues are addressed informally in other courses, he observed, "but within the hard-science curriculum, learning the science has to be the big thing, so often the students who have the most technical training have given the least thought to the related social issues." Sullivan also commented that he finds teaching an "issues" course more difficult than teaching a straight science course where the content is more circumscribed. "You have students with built-in mental blocks, and you have to start by motivating them before teaching the science. They often want to start out arguing from the seats of their pants instead of from knowledge. Teaching the course, I try to be fair and objective in presenting some of the dilemmas, in presenting some of the proposed solutions, and in presenting my own opinions. I'm not looking for agreement. The important thing is that the students be true to the data, that they reason logically, and that they advance coherent and intelligent arguments.

"Law and Education: Equality and Change in Higher Education," a seminar taught by Margaret Bonz, the College's affirmative-action officer, is a good example of several Education Department courses whose purview inevitably includes moral issues. Associate Chaplain Richard Hyde's freshman seminar, "Ethical Education," starts with the assumption "that you all will be ethical educators no matter what profession you enter, since ethical education goes on all the time and everyone engages in it for better or worse." Hyde asks students to articulate their own ethical principles, to speculate about the nature of a just society, and to take a stand on what he presents as some central moral issues violence and non-violence, the arms race, and abortion. "I'm trying to make people more thoughtful about the ethical implications of all human interaction," Hyde explained, "as well as to stress the practical seriousness of some of these problems." He sees challenging unchallenged opinions as part of his responsibility in class, but his emphasis is on encouraging people to articulate their opinions, not on argumentation.

IN response to the question of who is qualified to teach about ethics, Gert observed that "people not trained in philosophy teach ethics about as well as I would do teaching biology not very well." Paul Sullivan, whose training as a geneticist included the study of philosophy and theology at a Jesuit seminary, conceded a "certain level of incompetence" in the sciences in dealing systematically with ethical issues, but he pointed out that by virtue of the structure of our educational system distributive requirements notwithstanding the scientist "tends to receive more humanist training" than the humanist receives scientific training. The moral philosopher might counter by saying that generalized training in humanities has little to do with competence in teaching a rational way of making moral decisions that ethics is a specialized field in itself.

When they talk about morality, professors teaching courses as well as people talking at cocktail parties often fail to distinguish a theory of moral decision-making from intuitions about what is right or wrong in particular cases. It all gets lumped together in "ethics." At Dartmouth, there is a growing amount of interdisciplinary cooperation that goes a long way toward solving that problem. This cooperation, combining theoretical sophistication with technical competence in a specific field, most notably in the form of team-teaching, extends to the curricula of the professional schools and graduate programs.

Dartmouth's associated schools have, in recent years, been making the effort to provide opportunities within their curricula for systematic and explicit consideration of moral concerns facing doctors, engineers, and business professionals. In some cases this is accomplished through electives with a focus on ethics, most often through units in more generalized courses.

AT the Medical School, an elective in medical ethics, taught by Gert and Dr. Charles Culver, professor of psychiatry, has been offered to first- and second-year students for about ten years. Their unit on the ethics of treatment is part of a required psychiatry course, and they teach a "Philosophical Problems in Psychiatry" seminar required of psychiatry residents. In addition, they have been leading a monthly seminar for clinical nursing specialists, and Culver has directed workshops, sponsored by the Hastings Center, to provide clinical experience for academics outside of medicine who teach medical ethics. Other departments within the school community medicine, for example — are also involved in teaching medical ethics, either formally or informally, as moral concerns arise in the course of study.

Culver pointed out that only 15 to 20 per cent of the medical students take the medical ethics elective. The ideal, he said, would be for medical students to have more required study in ethics before beginning clinical rotations, to have seminars during the rotations focused on some of the ethical questions that come up in. the wards, and then, in the fourth year, to explore ethical issues on a deeper level, drawing on the students' clinical experience and medical knowledge. Some of this ideal could be realized at Dartmouth, Culver said, but he pointed out that it would be expensive in terms of faculty time and that ethics is just one of several topics competing for space in the new four-year curriculum.

The College's new master's program in Computer and Information Sciences has a required second-year course called "The Ethical and Social Impact of Computing." The program chairman, Stephen Garland '63, professor of mathematics, explained that the requirement stems from the assumption that in a professional course of study "you ought to get people to think about more than just how to do their jobs." The focus is on how computing affects business, individuals, and society as a whole how it changes patterns and perceptions of work. Some of the issuethat might be considered are the consequences of the decentralization of work as more people are able to use computers in performing their jobs at home, what happens when some of the "safety-valve" slack is removed from the money and banking system through electronic funds transfer, the protection of privacy, appropriate safeguards for computerized control of potentially hazardous technologies, and the assignment of responsibility in the event of a mistake or malfunction. "We have to sensitize people to the presence of these kinds of issues," Garland said, "give them some tools to deal with the moral questions, and try to bring people's technical knowledge to bear on solving the problems."

Dealing with the possibility of failure of a mechanical device or system is one of the main concerns that John Collier '72, director of Thayer School's Project Invente, introduces into the design-methodology course required of all degree-candidates in professional engineering. Collier spends three days on ethics in his design course more time than he spends on a variety of other topics presenting professional codes of ethics, considering when "whistleblowing" is called for, and talking about the place of safety in design. His own approach is case-oriented, but he invites Gert to present some rudiments of ethical theory. "You bump into ethical problems every time you design a product," Collier said. "You always have trade-offs between profits, liability, efficiency, and safety. With a new product, you develop an acceptable rate of failure in conjunction with a cost-benefit analysis. Sometimes you have the option of transferring the decision about risk to the product's user. We're not giving out any easy answers, just introducing some considerations. It could be that as an engineer you decide all you should design are wooden doors."

John Hennessey, who returned to fulltime teaching at Tuck in 1977 after serving six years as associate dean and eight years as dean, was quick to point out that Tuck's longstanding concern for the teaching of ethics is rooted in its institutional purpose, the interests of the faculty, and in the nature of the profession of management. He gave particular credit to Professor Wayne Broehl's work in ethics in a business and society course. There are opportunities throughout the curriculum, Hennessey said, for the consideration of a whole range of ethical issues from those stemming from the nature of capitalism to the potential conflicts between the requirements of career and private life. Nevertheless, he noted, there has been a recent interest in giving more formal and systematic consideration to business ethics in specific courses, an interest facilitated by the recent willingness of academic philosophers to recognize the "complexity and honorability of management and business." He added that there are "some very promising bridges" being built between theory and practical issues of concern to business professionals. "It seems the philosophers really want to apply ethics, and that gives us tremendous common cause."

Hennessey teaches a required first-year course in "Organizational Behavior" and a second-year elective called "Dilemmas of Management," both of which involve a certain amount of collaboration with Gert and use of his material. The "Dilemmas" course presents students with case studies that are variations on the theme of the; conflicting claims of individuals and organizations. In a thoughtful essay in the 1980 winter issue of Exchange, a teaching journal, Hennessey discussed the awkward position of values in organizational behavior courses. He mentioned the tensions between a supposedly value-free social science, the implicit value statements inevitably made in the practice of teaching, instructors' reluctance and lack of training to deal with values explicitly and systematically, and some students' desire "for a coherent philosophy which informs the use of power."

Describing his own "sharp" dilemma, Hennessey wrote, "On the one horn, I could try to avoid values and value questions at the risk of having the best students view my courses as some kind of synthetic human engineering, or I could include values and run the risk of irresponsible preaching of my own rationalized morality. I decided to accept the challenge of impalement on the second horn of the dilemma, because I have come to believe that values are essential to an understanding of organizational problems of enduring importance, and I am convinced that their inclusion need not involve preaching." Student reaction is mixed, ranging from interest so deep it affects career decisions, to cynicism, to hostility toward the notion of considering values other than the maximization of profits.

Hennessey and others are looking forward to the possibility of developing a formal, long-term business-ethics program, but he feels strongly about keeping ethics integrated into the whole curriculum, not isolated in one or two courses. He is also opposed to the idea of "sub-contracting" the responsibility of teaching ethics and stresses the importance of collaboration between the philosophers and the business professionals.

INTERDISCIPLINARY cooperation and collaborative efforts between the undergraduate and graduate faculties have distinguished the best of the teaching about ethics at Dartmouth. The theorists have been aiming much of their effort at practical issues while recognizing their lay status outside their own discipline. At the same time, many other faculty members are realizing the importance for their disciplines of a sophisticated and systematic sorting of moral concerns. It has been lack of faculty time, not willingness, that has been the main limitation on collaboration in classes. Beyond the team-teaching approach, groups of professors have been exploring ethical issues in two faculty programs for interdisciplinary discussion and research. Representatives of various disciplines have been meeting regularly to do work in "The Ethics, Politics, and Economics of Health Care" and also in "Philosophical Issues in Psychiatry."

The association between Gert and Culver, who are engaged in several teaching, curricular development, and publishing projects and who have gained more than amateur standing in each other's fields, is a good example of this kind of productive sharing of expertise. Gert did an "externship" in psychiatry, studying and working in the in-patient ward of the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Mental Health Center, and Culver spent a sabbatical studying moral philosophy at Oxford. They now hold adjunct appointments in each other's departments. A couple of years ago they obtained a Quality in Liberal Learning Grant from the Association of American Colleges that was used to develop further their work in ethics at the Medical School and to expand that activity to Thayer and Tuck. More recently, Gert obtained a four-year, $150,000 grant from the National Science Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities to continue the cross-disciplinary teaching and research of ethics in medicine, nursing, business, and engineering.

In his grant proposal, Gert wrote about his realization that "the relationship between an ethical theory and applied ethics was mutually beneficial. I had always known that serious work in applied ethics required an adequate theory, but I had not sufficiently realized how much the development of an adequate ethical theory required testing by application to real cases. ... I have learned, what I had already strongly suspected, that the resolution of moral disputes depends primarily on becoming clear about the relevant facts of the case. My theory helps to determine what kinds of facts are morally relevant, but it requires an expert in the field of the problem of concern to determine what the facts of the case really are."

ONE immediate effect of this kind of interdisciplinary cooperation between academic departments and between the undergraduate college and the associated professional schools has been to enrich the quality of teaching at all levels. Attempting to expand and institutionalize the work already in progress, a number of professors are formulating a proposal for the establishment of an academic center that would bring together people from a variety of disciplines with an interest in ethics, encourage collaborative teaching and research efforts, and support scholarship and teaching in the field of professional ethics. Because of Dartmouth's existing strength in the teaching of ethics, and because of the resources of the three graduate schools in such close proximity to the undergraduate college, proponents of the center see an exciting potential at Dartmouth for innovation and leadership.

Gregory Prince, associate dean of the faculty, pointed out this winter that various conceptions of the center range from "a box of stationery in someone's office" to an actual physical facility including a library and staff. He did say, however, that the objective of encouraging the consideration of ethics is fundamental to Dartmouth's purposes. "A liberal arts education," according to Prince, "trains one to think clearly, to judge and act wisely, and to communicate effectively." To strengthen and articulate the importance of ethical issues in all disciplines, he said, is to accomplish those general educational objectives. The academic concern for ethics is a contemporary expression of the College's original goals, he added. "We're trying to move back toward the model of a college where moral philosophy is integrated in all its activities."

Warner Traynham: "The issue is whether or not we are going to bring questions relatingto our institutional involvement in ethics to the surface and deal with them. I'm not persuaded that the best way to deal with ethics is always in an academic course. Someoneonce said that in a conflict of intellect and imagination, the imagination will always win.The best teachers recognize that. The imagination will have to be informed. That is part ofwhat the Tucker Foundation tries to do through the internship programs by putting people in real situations where they have to deal with ethical problems."

Bernard Gert [from The Moral Rules/: " 'Love thy neighbor as thyself' is one of thefavorite sayings. No one feels compelled to live by it; obviously only the very saintly caneven approach it. 'Live and let live,' on the other hand, is often regarded as merely advocating the easy way out. But 'live and let live' is probably the best statement of what themoral rules demand. Do not interfere with others; do not cause them any evil. . . Moralityshould not be regarded as providing a guide by which all men should try to live, thoughwith no hope of ever actually doing so. Morality should be regarded primarily asproviding the rules which everyman must obey no matter what his aim in life is.'

John Hennessey [in Exchange/: "Debating the intractable dilemmas may be the most valuable part of the ['Dilemmas ofManagement'] course, however, because it explores and tests thelimits of rationality and philosophy in defining executive responsibility in extreme conditions."

Dr. Charles Culver: "The old answer about teaching medicalethics is that 'we always teach ethics every time we teachanything.' That isn't entirely satisfactory. Most students get theirethics from watching older doctors. It would be good to havesomething a bit more comprehensive."

Pan! Sullivan: " 'Genetics and Society' is not just one of those discussion courses where students can come in and talk aboutanything that comes into their heads. We're trying to lay a scientific foundation before moving on to a consideration of the socialand moral issues."

Ronald Green [from Religious Reason): "What I hope to trace isthe way an independent and rationally constituted morality iscompelled to resort to one form or other of religious belief inorder to render its dictates coherent. . . that religion is a firm partof our entire procedure for making rational decisions."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

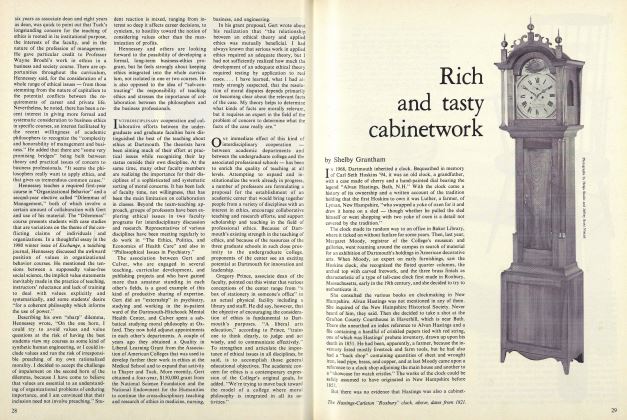

FeatureRich and tasty cabinetwork

March 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

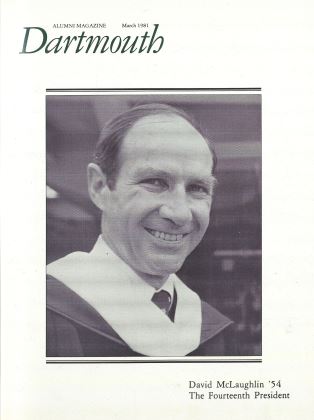

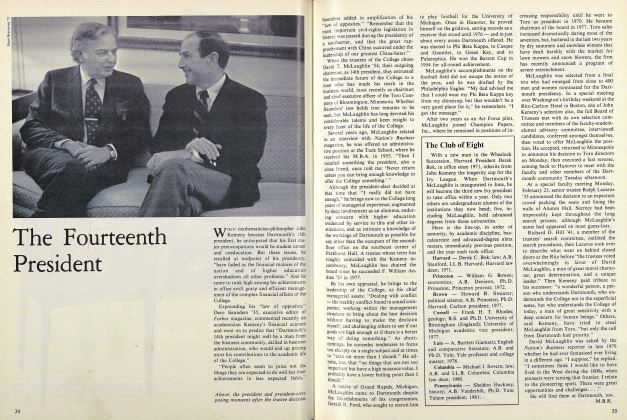

Cover StoryThe Fourteenth President

March 1981 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleImagining Beyond Limits

March 1981 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

March 1981 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1967

March 1981 By CLEMSON N. PAGE, JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1965

March 1981 By ROBERT D. BLAKE

Dan Nelson

-

Feature

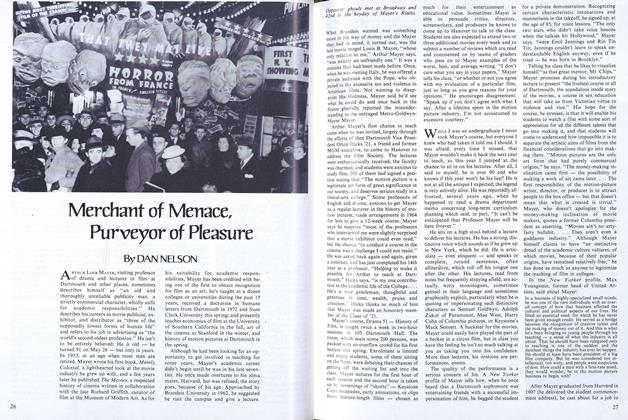

FeatureMerchant of Menace, Purveyor of Pleasure

JUNE 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureStalking the Student Athlete

MARCH 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureShhh. There still are idealists abroad and they're called the Peace Corps

JUNE 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureLife in High Places

April 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson

Features

-

Feature

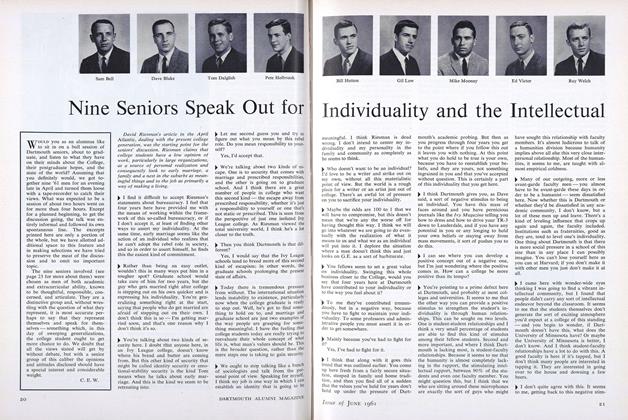

FeatureNine Seniors Speak Out for Individuality and the Intellectual

June 1961 -

Feature

FeatureTHE MOUNTAINEERS

Jan/Feb 2013 By BROUGHTON COBURN -

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshmen

December 1957 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Feature

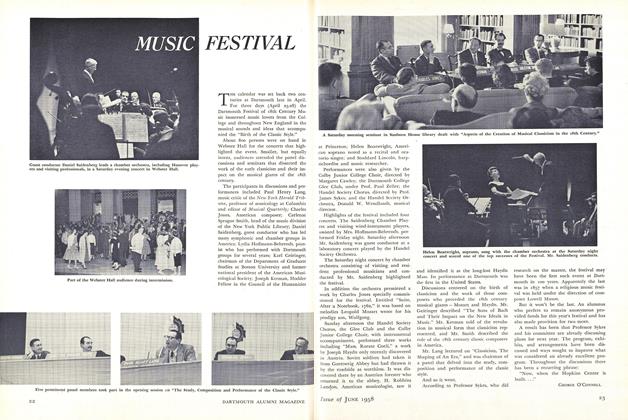

FeatureMUSIC FESTIVAL

June 1958 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureIntegrity

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Jayne Daigle Jones '86 -

Feature

FeatureYou Laughed

JUNE • 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77